Wikiversity

Contents

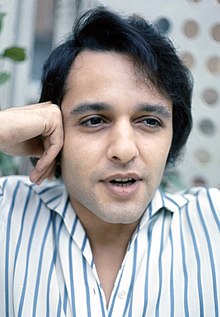

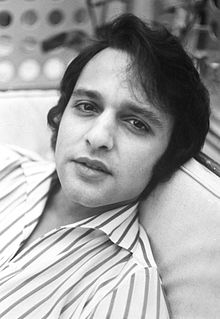

Sal Mineo | |

|---|---|

Mineo in 1973 | |

| Born | Salvatore Mineo Jr. January 10, 1939 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 12, 1976 (aged 37) |

| Cause of death | Murder (stab wound to the heart) |

| Resting place | Gate of Heaven Cemetery |

| Other names | The Switchblade Kid[1] |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1951–1976 |

| Known for | |

| Partners |

|

Salvatore Mineo Jr. (January 10, 1939 – February 12, 1976) was an American actor. He was best known for his role as John "Plato" Crawford in the drama film Rebel Without a Cause (1955), which earned him a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor at age 17, making him the fifth-youngest nominee in the category.

Mineo also starred in films such as Crime in the Streets, Giant (both 1956), Exodus (1960), for which he won a Golden Globe and received a second Academy Award nomination, The Longest Day (1962), John Ford's final western Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971).

Early life and education

Mineo was born in The Bronx, New York City, the son of coffin makers Josephine (née Alvisi; 1913–1989) and Salvatore Mineo Sr (1913–1972).[2][3] He was of Sicilian descent; his father was born in Italy and his mother, of Italian origin, was born in the United States. Mineo's sister Sarina (b. 1943), brothers Michael (1937–1984) and Victor (1935–2015) were also actors. He attended the Quintano School for Young Professionals[4][5] and was one of the few Italian-American actors of his era to keep their surname, saying he was proud of his heritage and identity.[6]

Acting career

Child actor

Mineo's mother enrolled him in dancing and acting school at an early age.[7] He had his first stage appearance in Tennessee Williams's play The Rose Tattoo (1951).[8] He also played the young prince opposite Yul Brynner in the stage musical The King and I. Brynner took the opportunity to help Mineo better himself as an actor.[1]

On May 8, 1954, Mineo portrayed the Page (lip-synching to the voice of mezzo-soprano Carol Jones) in the NBC Opera Theatre's production of Richard Strauss's Salome (in English translation), set to Oscar Wilde's play.[9][10] Elaine Malbin performed the title role, and Peter Herman Adler conducted Kirk Browning's production.

As a teenager, Mineo appeared on ABC's musical quiz program Jukebox Jury. Mineo made several television appearances before making his screen debut in the Joseph Pevney film Six Bridges to Cross (1955). He beat out Clint Eastwood for the role.[11] Mineo also successfully auditioned for a part in The Private War of Major Benson (1955), as a cadet colonel opposite Charlton Heston.[12]

Rebel Without a Cause and stardom

Mineo's breakthrough as an actor came in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), in which he played John "Plato" Crawford, a sensitive teenager smitten with main character Jim Stark (played by James Dean).[8] Mineo's performance resulted in an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor and he became the fifth-youngest nominee in the category, at the age of 17.[1] Mineo's biographer Paul Jeffers recounted that Mineo received thousands of letters from young female fans, was mobbed by them at public appearances, and further wrote: "He dated the most beautiful women in Hollywood and New York City."[13]

In Giant (1956), Mineo played Angel Obregon II, a Mexican boy killed in World War II. Many of his subsequent roles were variations of his role in Rebel Without a Cause, and he was typecast as a troubled teen.[14] In the Disney adventure Tonka (1958), for instance, Mineo starred as a young Sioux named White Bull who traps and domesticates a clear-eyed, spirited wild horse named Tonka that becomes the famous Comanche, the lone survivor of Custer's Last Stand. By the late 1950s, Mineo was a major celebrity. He was sometimes referred to as the "Switchblade Kid", a nickname he earned from his role as a criminal in the movie Crime in the Streets (1956).[1]

In 1957, Mineo made a brief foray into pop music by recording a handful of songs and an album. Two of his singles reached the Top 40 in the United States' Billboard Hot 100.[15] The more popular of the two, "Start Movin' (In My Direction)", reached No. 9 on Billboard's pop chart. It sold over one million copies and was awarded a gold disc.[16] He starred as drummer Gene Krupa in the movie The Gene Krupa Story (1959), directed by Don Weis with Susan Kohner, James Darren, and Susan Oliver. He appeared as the celebrity guest challenger on the June 30, 1957, episode of What's My Line?[17]

Mineo made an effort to break his typecasting.[18] In addition to his roles as a Native American brave in Tonka (1958),[18] and a Mexican boy in Giant (1956),[19] he played a Jewish Holocaust survivor in Exodus (1960); for his work in Exodus, he won a Golden Globe Award and received his second Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[20][21][18]

Career shift

By the early 1960s, Mineo was becoming too old to play the type of role that had made him famous, and rumors of his homosexuality led to his being considered inappropriate for leading roles. For example, he auditioned for David Lean's film Lawrence of Arabia (1962) but was not hired.[7] Mineo appeared in The Longest Day (1962), in which he played a private killed by a German after the landing in Sainte-Mère-Église. Mineo was baffled by his sudden loss of popularity, later saying: "One minute it seemed I had more movie offers than I could handle; the next, no one wanted me."[22]

Mineo was the model for Harold Stevenson's painting The New Adam (1963). Now in the Guggenheim Museum's permanent collection, the painting is considered "one of the great American nudes".[23] Mineo also appeared on the Season 2 episode of The Patty Duke Show: "Patty Meets a Celebrity" (1964).[24][25][26][27]

Mineo's role as a stalker in Who Killed Teddy Bear (1965), which co-starred Juliet Prowse, did not seem to help his career. Although his performance was praised by critics, he found himself typecast again—this time as a deranged criminal.[28][29] The high point of this period was his portrayal of Uriah in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).[30] Mineo guest-starred in an episode of the TV series Combat! in 1966, playing the role of a GI wanted for murder.[31] He did two more appearances on the same show, including appearing in an installment with Fernando Lamas.[32]

In 1969, Mineo returned to the stage to direct a Los Angeles production of the gay-themed play Fortune and Men's Eyes (1967), featuring then-unknown Don Johnson as Smitty and Mineo as Rocky. The production received positive reviews, although its expanded prison rape scene was criticized as excessive and gratuitous.[33][non-primary source needed] Mineo's last role in a motion picture was a small part in the film Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971);[34] he played the chimpanzee Dr. Milo.

In December 1972, Mineo stage-directed the Gian Carlo Menotti short opera The Medium in Detroit.[35] Muriel Costa-Greenspon portrayed the title character, Madame Flora, and Mineo played the mute, Toby. In 1975, Mineo appeared as Rachman Habib, the assistant to a murderous consular head (portrayed by Hector Elizondo) of a Middle Eastern country, in the Columbo episode "A Case of Immunity," on NBC-TV. One of his last roles was a guest spot on the TV series S.W.A.T. (1975),[36] in which he portrayed a cult leader similar to Charles Manson.

By 1976, Mineo's career had begun to turn around.[37] While playing the role of a bisexual burglar in a series of stage performances of the comedy P.S. Your Cat Is Dead in San Francisco, Mineo received substantial publicity from many positive reviews; he moved to Los Angeles along with the play.[38][39][40]

Personal life

In a 1972 interview with Boze Hadleigh, Mineo confirmed his bisexuality.[41] Mineo met English-born actress Jill Haworth on the set of the film Exodus in 1960, in which they portrayed young lovers. Mineo and Haworth were in an on-and-off relationship for many years. They were engaged to be married at one point. According to Mineo biographer Michael Gregg Michaud, Haworth cancelled the engagement after she caught Mineo engaging in sexual relations with a man.[42] The two remained very close friends until Mineo's death.[42][43] Mineo expressed disapproval of Haworth's brief relationship with television producer Aaron Spelling, who was 22 years older than she. One night, when Mineo found Haworth and Spelling at a private Beverly Hills nightclub, he punched Spelling in the face, yelling, "Do you know how old she is? What are you doing with her at your age?"[42] At the time of his death, he was in a six-year relationship with actor and retired acting coach Courtney Burr III.[42][44]

Death

On the night of February 12, 1976, Mineo returned home from a rehearsal for the play P.S. Your Cat Is Dead at 10:00 pm.[45] After parking his car in the carport below his West Hollywood apartment, he was stabbed in the heart by a mugger.[46][47] Mineo was found lying and bleeding profusely in the parking alley by his neighbor Raymond Evans, who had heard his cries for help, but Mineo was only able to walk a few steps, after which he collapsed immediately and was pronounced dead at the age of 37 due to massive hemorrhage.[45]

Lionel Ray Williams, a young pizza delivery man with a long criminal record, was convicted and sentenced in March 1979 to 57 years in prison for killing Mineo and also for committing ten robberies. Although considerable confusion existed as to what witnesses had seen in the dark the night Mineo was murdered, Williams claimed to have had no idea who Mineo was. Corrections officers later said they had overheard Williams admitting to the stabbing.[37] Williams' wife later confirmed that on the night Mineo died, he had come home with blood on his shirt. After several years of speculation about the motives for the murder, the police investigation concluded that it was a random robbery.[48] Williams was paroled in 1990 after serving 12 years.[49]

A funeral for Mineo was held at Most Holy Trinity Church, Mamaroneck, on February 17, 1976, and was attended by 250 mourners.[50] Mineo was buried at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.[51]

Filmography

Film

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | The Vision of Father Flanagan | Les | TV movie |

| 1952 | A Woman for the Ages | Charles | TV movie |

| 1953 | Omnibus | Paco | "The Capitol of the World" |

| 1954 | Janet Dean, Registered Nurse | Tommy Angelo | "The Magic Horn" |

| 1955 | Big Town | "Juvenile Gangs" | |

| 1955 | Omnibus | "The Bad Men" | |

| 1955 | The Philco Television Playhouse | "The Trees" | |

| 1955 | Frontiers of Faith | "The Man on the 6:02" | |

| 1956 | Look Up and Live | "Nothing to Do" | |

| 1956 | The Alcoa Hour | Paco | "The Capitol of the World", "The Magic Horn" |

| 1956 | Westinghouse Studio One | "Dino" | |

| 1956 | Look Up and Live | "Nothing to Do" | |

| 1956 | Lux Video Theatre | "Tabloid" | |

| 1956 | Screen Directors Playhouse | "The Dream" | |

| 1956 | Climax! | Miguel | "Island in the City" |

| 1957 | The Ed Sullivan Show | Himself | Episodes 10.42, 10.48 |

| 1957 | Kraft Suspense Theatre | Tony Russo | "Barefoot Soldier", "Drummer Man" |

| 1957 | Kraft Music Hall | Himself | Episode 10.8 |

| 1958 | The DuPont Show of the Month | Aladdin | "Cole Porter's Aladdin" |

| 1958 | Pursuit | Jose Garcia | "The Garcia Story" |

| 1959 | The Ann Sothern Show | Nicky Silvero | "The Sal Mineo Story" |

| 1962 | The DuPont Show of the Week | Coke | "A Sound of Hunting" |

| 1963 | The Greatest Show on Earth | Billy Archer | "The Loser" |

| 1964 | Kraft Suspense Theatre | Ernie | "The World I Want" |

| 1964 | Dr. Kildare | Carlos Mendoza | "Tomorrow is a Fickle Girl" |

| 1964 | Combat! | Private Kogan | "The Hard Way Back" |

| 1965 | The Patty Duke Show | Himself | "Patty Meets a Celebrity" |

| 1965 | Burke's Law | Lew Dixon | "Who Killed the Rabbit's Husband?" |

| 1966 | Combat! | Vinnick | "Nothing to Lose" |

| 1966 | Combat! | Marcel Paulon | "The Brothers" |

| 1966 | Mona McCluskey | "The General Swings at Dawn" | |

| 1966 | Run for Your Life | Tonio | "Sequestro!: Parts 1 and 2" |

| 1966 | Court Martial | Lt. Tony Bianchi | "The House Where He Lived" |

| 1966 | The Dangerous Days of Kiowa Jones | Bobby Jack Wilkes | TV movie |

| 1967 | Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Doctoroff | "A Song Called Revenge" |

| 1967 | Stranger on the Run | George Blaylock | TV movie |

| 1968 | Hawaii Five-O | Bobby George | "Tiger By The Tail" |

| 1969 | The Name of the Game | Sheldon | "A Hard Case Of The Blues" |

| 1970 | Mission Impossible | Mel Bracken | Flip Side |

| 1970 | The Challengers | Angel de Angelo | TV movie |

| 1970 | The Name of the Game | Wade Hillary | "So Long, Baby, and Amen" |

| 1971 | My Three Sons | Jim Bell | "The Liberty Bell" |

| 1971 | The Immortal | Tsinnajinni | "Sanctuary" |

| 1971 | Dan August | Mort Downes | "The Worst Crime" |

| 1971 | In Search of America | Nick | TV movie |

| 1971 | How to Steal an Airplane | Luis Ortega | TV movie |

| 1972 | The Family Rico | Nick Rico | TV movie |

| 1973 | Griff | President Gamal Zaki | "Marked for Murder" |

| 1973 | Harry O | Walter Scheerer | "Such Dust as Dreams Are Made On" |

| 1974 | Tenafly | Jerry Farmer | "Man Running" |

| 1974 | Police Story | Stippy | "The Hunters" |

| 1975 | Columbo | Rachman Habib | "A Case of Immunity" |

| 1975 | Hawaii Five-O | Eddie | "Hit Gun for Sale" |

| 1975 | Harry O | Broker | "Elegy for a Cop" |

| 1975 | SWAT | Roy | "Deadly Tide: Parts 1 and 2" |

| 1975 | SWAT | Joey Hopper | "A Coven of Killers" |

| 1975 | Police Story | Fobbes | "Test of Brotherhood" |

| 1976 | Ellery Queen | James Danello | "The Adventure of the Wary Witness" |

| 1976 | Joe Forrester | Parma | "The Answer", (final appearance) |

Awards and nominations

| Institution | Category | Year | Work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Supporting Actor | 1956 | Rebel Without a Cause | Nominated |

| 1961 | Exodus | Nominated | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor | 1961 | Won | |

| Primetime Emmy Awards | Best Single Performance by an Actor | 1957 | Studio One | Nominated |

| Laurel Awards | Top Male Supporting Performance | 1961 | Exodus | Won |

See also

- List of oldest and youngest Academy Award winners and nominees – Youngest nominees for Best Actor in a Supporting Role

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

- List of LGBTQ Academy Award winners and nominees

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Bell, Rachael. "The Switchblade Kid: The Life and Death of Sal Mineo". Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ Mendez, Antonio (January 2006). Guía del cine clásico: Protagonistas – Antonio Mendez – Google Books. Vision Libros. ISBN 9788498213881. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Harper, Valerie (January 15, 2013). I, Rhoda. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451699487 – via Google Books.

- ^ Katz, Mike; Kott, Crispin (June 1, 2018). Rock and Roll Explorer Guide to New York City. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781493037049 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sal Mineo Newstand". Salmineo.com. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Noe, Denise. "The Murder of Sal Mineo". Archived from the original on June 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Holliday, Peter J. (November 8, 2008) [2002]. "Mineo, Sal (1939–1976)". In Summers, Claude J. (ed.). glbtq: An encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer culture. Chicago: glbtq, Inc. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012.

- ^ "Comet Over Hollywood's Gone Too Soon: Sal Mineo". Kirksville Daily Express – Kirksville, MO. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (June 13, 2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675 – via Google Books.

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: HarperCollins. p. 63. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- ^ Ellis, Chris; Ellis, Julie (July 27, 2005). The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder: Murder Played Out in the Spotlight of Maximum Publicity. Berghahn Books. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-57181-140-0. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Jeffers, Paul (2000). Sal Mineo: His Life, Murder, and Mystery. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-0777-1.

- ^ Smith, Laura C. (February 10, 1995). "Untimely End for a 'Rebel'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ "Sal Mineo Mini biography". Salmineo.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 94. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ What's My Line? – Sal Mineo; Ernie Kovacs (panel); Martin Gabel (panel) (June 30, 1957)

- ^ a b c "The Murder of Sal Mineo Crime Magazine". Crimemagazine.com.

- ^ "The Advocate". Here Publishing. August 19, 1997 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Book helps rediscover murdered Hollywood star". CNN.

- ^ "Watch the Trailer for James Franco's "Sal" Biopic". Nbcchicago.com. October 2, 2013.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (June 13, 2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675 – via Google Books.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (September 30, 2005). "Exposure for a Nude". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ "The Patty Duke Show: Season 2". Amazon. February 9, 2010.

- ^ Egner, Jeremy (March 30, 2016). "Video: Remembering Patty Duke". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Patty Duke Show S2E19 Patty Meets a Celebrity". February 14, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Patty Meets a Celebrity, Episode 55 Original Air Date January 20, 1965 List of The Patty Duke Show episodes

- ^ "CLOSED – The Sal Mineo Story "Rebel with A Cause" – Feb 9th &10, 2016". January 18, 2016.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (June 13, 2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Desert Sun 24 November 1962 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". Cdnc.ucr.edu.

- ^ Davidsmeyer, Jo. "Nothing to Lose". Combat! Fan Site. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (June 13, 2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675 – via Google Books.

- ^ "INTERVIEW WITH DON JOHNSON, AGE 20 ~ by Marvin Jones | Facebook" – via Facebook.

- ^ "Actor Sal Mineo is killed in Hollywood". History.com.

- ^ Stevenson, Harold. "The New Adam Article". Archived from the original on September 22, 2008.

- ^ Michaud, Michael Gregg (June 13, 2011). Sal Mineo: A Biography. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 9780307716675 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Ellis, Chris; Ellis, Julie (2005). The Mammoth Book of Celebrity Murder. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 419–422. ISBN 0-7867-1568-5.

- ^ "Sal Mineo Knifed to Death in Hollywood". The New York Times. February 14, 1976.

- ^ "James Ellroy: Cracking the Case of Murdered Actor Sal Mineo". The Hollywood Reporter. December 21, 2018.

- ^ "Sal Mineo". Biography.com.

- ^ "Boze Hadleigh interview with Sal Mineo, 1972". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Michael Gregg Michaud. "Sal Mineo: A Biography". Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ Michael Gregg Michaud. "The Relevance of Sal Mineo". Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ Matthew Carey. "Book helps rediscover murdered Hollywood star". CNN. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ a b UPI (February 14, 1976). "Sal Mineo Knifed to Death in Hollywood". The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Actor Sal Mineo Is Stabbed to Death". Los Angeles Times. February 12, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ Rachael Bell (2008). "The Switchblade Kid: The Life and Death of Sal Mineo". TruTV. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

The autopsy revealed that Sal died of a single stab wound to the heart.

- ^ "Sal Mineo Murder Site | One Archives". One.usc.edu.

- ^ "Short Story Mistaken for Confession in Slaying of Actor". Prweb.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2005.

- ^ "250 Attend Sal Mineo Funeral; Actor Is Called 'Gentle Person'". The New York Times. February 18, 1976.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 32658-32659). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

Sources

- Frascella, Lawrence; Weisel, Al (2005). Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause. Touchstone. ISBN 0-7432-6082-1.

- Gilmore, John (1998). Laid Bare: A Memoir of Wrecked Lives and the Hollywood Death Trip. Amok Books. ISBN 1-878923-08-0.

- Johansson, Warren; Percy, William A (1994). Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence. Harrington Park Press. p. 91.

External links

- Sal Mineo at IMDb

- Sal Mineo at the Internet Broadway Database

- Sal Mineo at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Abel, Bob (February 1970). "Sal Mineo interviewed". SalMineo.com. Cavalier. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006.