Wikiversity

Contents

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Kama (Sanskrit: काम, IAST: kāma) is the concept of pleasure, enjoyment and desire in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. It can also refer to "desire, wish, longing" in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh literature.[2][3][4] However, the term is also used in a technical sense to refer to any sensory enjoyment, emotional attraction or aesthetic pleasure experienced in connection with the arts, dance, music, painting, sculpture, and nature.[1][5]

In contemporary literature kama is often used to connote sexual desire and emotional longing,[3][4][6] but the ancient concept is more expansive, and broadly refers to any desire, wish, passion, pleasure, or enjoyment of art and beauty, the aesthetic, enjoyment of life, affection, love and connection, and enjoyment of love with or without sexual connotations.[3][7]

In Hindu thought, kama is one among the three items of the trivarga and is one of the four Purusharthas, which are the four beneficial domains of human endeavor.[8][9] In Hinduism it is considered an essential and healthy goal of human life to pursue Kama without sacrificing the other three Purusharthas: Dharma (virtuous, ethical, moral life), Artha (material needs, income security, means of life) and Moksha (liberation, release, self-realization).[10][8][11][12] In Buddhism and Jainism kama is to be overcome in order to obtain the goal of liberation from rebirth. But while kama is viewed as an obstacle for Buddhist and Jain monks and nuns, it is recognized as legitimate domain of activity for laity.[13]

Definition in Hinduism

In contemporary Indian literature, kama is often used to refer to sexual desire. However, Kama more broadly refers to any sensory enjoyment, emotional attraction and aesthetic pleasure such as from the arts, dance, music, painting, sculpture, and nature.[1][5]

Kama can refer to "desire, wish, or longing".[2]

The concept of kama is found in some of the earliest known verses in the Vedas. For example, Book 10 of the Rig Veda describes the creation of the universe from nothing by the great heat. In hymn 129 (RV 10.129.4) it states[clarification needed]:

कामस्तदग्रे समवर्तताधि मनसो रेतः परथमं यदासीत |

सतो बन्धुमसति निरविन्दन हर्दि परतीष्याकवयो मनीषा ||[14]

Thereafter rose Desire in the beginning, Desire the primal seed and germ of Spirit,

Sages who searched with their heart's thought discovered the existent's kinship in the non-existent.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, one of the oldest Upanishads of Hinduism, uses the term kama, also in a broader sense, to refer to any desire:

Man consists of desire (kama),

As his desire is, so is his determination,

As his determination is, so is his deed,

Whatever his deed is, that he attains.— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 7th Century BC[16]

Ancient Indian literature such as the Epics, which followed the Upanishads, develop and explain the concept of kama together with Artha and Dharma. The Mahabharata, for example, provides one of the expansive definitions of kama. The Epic describes kama to be any agreeable and desirable experience (pleasure) generated by the interaction of one or more of the five senses with anything associated with that sense, and whilst in harmony with the other goals of human life (dharma, artha and moksha).[17]

Kama is often used to refer to kamana (desire, longing or appetite). Kama, however, is more than kamana. Kama includes desire, wish, longing, emotional connection, love, appreciation, pleasure, and enjoyment.[5]

Vatsyayana, the author of the Kamasutra, describes kama as happiness that is a manasa vyapara (phenomenon of the mind). Just like the Mahabharata, Vatsyayana's Kamasutra defines kama as any pleasure an individual experiences from the world, with one or more senses: hearing, seeing, tasting, smelling, and feeling, in harmony with one's mind and soul.[11]

Experiencing harmonious music is kama, as is being inspired by natural beauty, the aesthetic appreciation of a work of art, and admiring with joy something crafted by another human being.

Vatsyayana's Kamasutra is often misunderstood to be a book solely about sexual and intimate relationships, but it was written as a guide to the nature of love, sexuality, finding a life partner, maintaining one's love life, and emotional fulfillment in life. In its discourse on kama it describes many forms of art, dance, and music, along with sex, as the means to pleasure and enjoyment.[17]

Kama is one's appreciation of incense, candles, music, scented oil, yoga stretching and meditation, and experiencing the heart chakra. The heart chakra is associated with love, compassion, charity, balance, calmness, and serenity, and is considered to be a seat of devotional worship. Opening the heart chakra is to experience an awareness of divine communion and joy in communion with deities and the self (Atman).[18]

John Lochtefeld describes kama as desire, noting that it often refers to sexual desire in contemporary literature, but in ancient Indian literature kāma includes any kind of attraction and pleasure such as those deriving from the arts.

Karl Potter describes[19] kama as an attitude and capacity. A little girl who hugs her teddy bear with a smile is experiencing kama. Two lovers in an embrace are experiencing kama. During these experiences the person feels more complete, fulfilled, and whole by experiencing that connection and nearness. This, in the Indian perspective, is kāma.[19]

Hindery notes the varying and diverse descriptions of kama in ancient Indian texts. Some texts, such as the Epic Ramayana, describe kama as the desire of Rama for Sita — a desire that transcends the physical and marital into a love that is spiritual, and something that gives Rama his meaning of life, his reason to live.[20] Sita and Rama both frequently express their unwillingness and inability to live without the other.[21] This romantic and spiritual description of kama in the Ramayana by Valmiki is more specific, observes Hindery[20] and others,[22] than the broader and more inclusive descriptions of kama, for example in the law codes of smriti by Manu.

Gavin Flood describes[23] kama as experiencing the positive emotional state of love whilst also not sacrificing one's dharma (virtuous, ethical behavior), artha (material needs, income security) and one's journey towards moksha (spiritual liberation, self-realization).

Importance of kama in Hinduism

In Hinduism, kama is regarded as one of the four proper and necessary objectives or goals of human life (purusharthas), the others being Dharma (virtuous, proper, moral life), Artha (material prosperity, income security, means of life) and Moksha (liberation, release, self-actualization).[12][24]

Relative precedence among artha and dharma

Ancient Indian literature emphasizes that dharma precedes and is essential. If dharma is ignored, artha and kama lead to social chaos.[25]

Vatsyayana in Kama Sutra recognizes relative value of three goals as follows: artha precedes kama, while dharma precedes both kama and artha.[11] Vatsyayana, in Chapter 2 of Kama Sutra, presents a series of philosophical objections argued against kama and then offers his answers to refute those objections. For example, Vatsyayana acknowledges that one objection to kama (pleasure, enjoyment) is this concern that kāma is an obstacle to moral and ethical life, to religious pursuits, to hard work, and to the productive pursuit of prosperity and wealth. Objectors claim that the pursuit of pleasure encourages individuals to commit unrighteous deeds that bring distress, carelessness, levity and suffering later in life.[26] These objections were then answered by Vatsyayana, with the declaration that kama is as necessary to human beings as food, and kama is holistic with dharma and artha.

Necessity for existence

Just like good food is necessary for the well-being of the body, good pleasure is necessary for the healthy existence of a human being, suggests Vatsyayana.[27] A life devoid of pleasure and enjoyment—sexual, artistic, or nature—is hollow and empty. Just like no one should stop farming crops even though everyone knows herds of deer exist and will try to eat the crop as it grows up, in the same way claims Vatsyayana, one should not stop one's pursuit of kama because dangers exist. Kama should be followed with thought, care, caution and enthusiasm, just like farming or any other life pursuit.[27]

Vatsyayana's book the Kama Sutra, in parts of the world, is presumed or depicted as a synonym for creative sexual positions; in reality, only 20% of Kama Sutra is about sexual positions. The majority of the book, notes Jacob Levy,[28] is about the philosophy and theory of love, what triggers desire, what sustains it, how and when it is good or bad. Kama Sutra presents kama as an essential and joyful aspect of human existence.[29]

Holistic

Vatsyayana claims kama is never in conflict with dharma or artha, rather all three coexist and kama results from the other two.[11]

A man practicing Dharma, Artha and Kama enjoys happiness now and in future. Any action which conduces to the practice of Dharma, Artha and Kama together, or of any two, or even one of them should be performed. But an action which conduces to the practice of one of them at the expense of the remaining two should not be performed.

— Vatsyayana, The Kama sutra, Chapter 2[30]

In Hindu philosophy, pleasure in general, and sexual pleasure in particular, is neither shameful nor dirty. It is necessary for human life, essential for well-being of every individual, and wholesome when pursued with due consideration of dharma and artha. Unlike the precepts of some religions, kama is celebrated in Hinduism, as a value in its own right.[31] Together with artha and dharma, it is an aspect of a holistic life.[5][32] All three purusharthas—Dharma, Artha and Kama—are equally and simultaneously important.[33]

Stages of life

Some[11][34] texts in ancient Indian literature observe that the relative precedence of artha, kama and dharma are naturally different for different people and different age groups. In a baby or child, education and kāma (artistic desires) take precedence; in youth kāma and artha take precedence; while in old age dharma takes precedence.

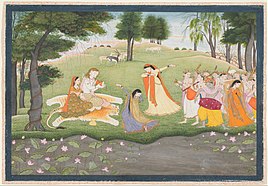

Deity

Kama is deified as Kamadeva and his consort Rati. Deity Kama is comparable to the Greek deity Eros—they both trigger human sexual attraction and sensual desire.[6][35] Kama rides a parrot, and the deity is armed with bow and arrows to pierce hearts. The bow is made of sugarcane stalk, the bowstring is a line of bees, and the arrows are tipped with five flowers representing five emotions-driven love states.[36] The five flowers on Kama arrows are lotus flower (infatuation), ashoka flower (intoxication with thoughts about the other person), mango flower (exhaustion and emptiness in absence of the other), jasmine flower (pining for the other) and blue lotus flower (paralysis with confusion and feelings). These five arrows also have names, the last and most dangerous of which is Sammohanam, infatuation.[37]

Kama is also known as Ananga (literally "one without body") because desire strikes formlessly, through feelings in unseen ways.[6] The other names for deity Kama include Madan (he who intoxicates with love), Manmatha (he who agitates the mind), Pradyumna (he who conquers all) and Kushumesu (he whose arrows are flowers).[38]

In Buddhism

(See also Buddhism and sexuality)

While in a narrow sense kāma refers to sexuality, it also refers to a broader domain of sensuality. In early Buddhist thought kāma has three general meanings. Psychologically, kāma refers to the subjective desire for sexual or sensual pleasure. Secondly, kāma may also refer to the phenomenological experience of sensual pleasure. Lastly, kāma may also refer to the objects of pleasure, or the types of objects and actions that are believed to give rise to experiences of sensual pleasure.[39] Kāma is central in early Buddhist cosmology, doctrine, and in the program of monastic discipline (vinaya).

Kama in Buddhist cosmology

The Buddhist cosmos consists of three hierarchically arranged realms (bhava or dhātu): the Desire Realm (kāmabhava), the Form Realm (rūpabhava), and the Formless Realm (arūpabhava). All beings inhabiting the Desire Realm, including human beings, animals, hungry ghosts, and the inhabitants of the various Buddhist heavens and hells, are considered to be afflicted by deep-seated sensual desire (kāma). The upper two levels of the cosmos are inhabited by beings who have either severely attenuated or nearly eradicated sensual desire through advanced meditative practice.[40] The Buddhist heavens, especially the Tāvatiṃsa heaven, is portrayed in Buddhist literature as saturated with the objects of sensual enjoyment. Such enjoyment is therefore regarded as a positive reward for ethical conduct, a result of one's merit (puñña) or good karma.[41]

Kama in Buddhist doctrine

In early Buddhist doctrine, the taint of sensuality (kāma-āsava) is one of the three (sometimes four) psychological taints (āsava) that must be eradicated for the attainment of awakening. In the Buddha's first sermon, the Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta, the "desire for sensual pleasure" (kāmataṇhā) is enumerated as one of the three forms of desire (taṇhā) that entrap beings in the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra).[42]

In the Buddhist Pali Canon, Gautama Buddha renounced (Pali: nekkhamma) sensuality (kama) as a route to Enlightenment.[43] Some Buddhist lay practitioners recite daily the Five Precepts, a commitment to abstain from "sexual misconduct" (kāmesu micchacara กาเมสุ มิจฺฉาจารา).[44] Typical of Pali Canon discourses, the Dhammika Sutta (Sn 2.14) includes a more explicit correlate to this precept when the Buddha enjoins a follower to "observe celibacy or at least do not have sex with another's wife."[45]

Kama in monastic law and precepts

Because the monastic vocation is premised on the renunciation of kāma, there are many rulings in monastic law (vinaya) that prohibit activities and practices that in the context of ancient India were associated with sensuality.[46] In the Pali Vinaya (Vinaya Piṭaka), this first and foremost includes abstaining from sex and other forms of sexual activity such as masturbation and intimate relations between the sexes. Beyond sexuality, monastic law also prohibits engagement in a wide variety of activities deemed as sensual. This includes the use of various kinds of luxury items, such as the use of perfumes (gandha), cosmetics (vilepana), garlands (mālā), bodily adornments and ornamentation (maṇḍana-vibhūsanaṭṭhāna), lavish furnishings, ostentatious clothing, and other such items. It also includes abstaining from various forms of musical, song, and dance performances.[47] The term kāma-guṇa is used in the Pali Buddhist literature to refer to the kinds of objects whose use or appropriation is believed to give rise to sensual pleasure.[48] [49]

Many of these are also included among the ten rules of training (sikkhāpada) observed by novices (sāmaṇera, sāmaṇerī), and figure among the eight precepts observed by Buddhist laity on special ritual occasions such as the fortnightly uposatha.[50] This includes abstaining from sex, the use of garlands, cosmetics, ornamentation, and lavish beds and bedding as well as attending musical, song, and dance performances (naccagītavāditavisūkadassanā). The association of these kinds of activities with sensuality is also reflected in the Kāmasūtra.[51] [52]

See also

- Kamashastra

- Kama Sutra

- Arishadvargas, six enemies

- Alcmaeon (mythology)

- Buddhist cosmology of the Theravada school

- Cupid

- Hinduism and LGBT topics

- Kaam, a word with a similar meaning

References

- ^ a b c See:

- ^ a b Monier Williams, काम, kāma Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine Monier-Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary, pp 271, see 3rd column

- ^ a b c Macy, Joanna (August 1975). "The Dialectics of Desire". Numen. 22 (2). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 145–160. doi:10.1163/156852775X00095. eISSN 1568-5276. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 3269765. S2CID 144148663.

- ^ a b Lang, Karen C. (June 2015). Mittal, Sushil (ed.). "When the Vindhya Mountains Float in the Ocean: Some Remarks on the Lust and Gluttony of Ascetics and Buddhist Monks". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 19 (1/2). Boston: Springer Verlag: 171–192. doi:10.1007/s11407-015-9176-z. eISSN 1574-9282. ISSN 1022-4556. JSTOR 24631797. S2CID 145662113.

- ^ a b c d R. Prasad (2008), History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Volume 12, Part 1, ISBN 978-8180695445, pp 249-270

- ^ a b c James Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 1, Rosen Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 340.

- ^ Lorin Roche. "Love-Kama". Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ a b Salagame, Kiran K. (2013). "Well-being from the Hindu/Sanātana Dharma Perspective". In Boniwell, Ilona; David, Susan A.; Ayers, Amanda C. (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557257.013.0029. ISBN 9780199557257. S2CID 148784481.

- ^ Olivelle, Patrick (2019). "From trivarga to puruṣārtha". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 139 (2): 381. ISSN 2169-2289.

- ^ Zysk, Kenneth (2018). "Kāma". In Basu, Helene; Jacobsen, Knut A.; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 7. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-5019_BEH_COM_2050220. ISBN 978-90-04-17641-6. ISSN 2212-5019.

- ^ a b c d e The Hindu Kama Shastra Society (1925), The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, University of Toronto Archives, pp. 8

- ^ a b see:

- A. Sharma (1982), The Puruṣārthas: a study in Hindu axiology, Michigan State University, ISBN 9789993624318, pp 9-12; See review by Frank Whaling in Numen, Vol. 31, 1 (Jul., 1984), pp. 140-142;

- A. Sharma (1999), The long uruṣārthas: An Axiological Exploration of Hinduism Archived 2020-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Summer, 1999), pp. 223-256;

- Chris Bartley (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, Editor: Oliver Learman, ISBN 0-415-17281-0, Routledge, Article on Purushartha, pp 443

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Rig Veda Book 10 Hymn 129 Archived 2018-02-16 at the Wayback Machine Verse 4

- ^ Ralph Griffith (Translator, 1895), The Hymns of the Rig veda, Book X, Hymn CXXIX, Verse 4, pp 575

- ^ Klaus Klostermaier, A Survey of Hinduism, 3rd Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pp. 173-174

- ^ a b R. Prasad (2008), History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Volume 12, Part 1, ISBN 978-8180695445, Chapter 10, particularly pp 252-255

- ^ "Kama - Hindupedia, the Hindu Encyclopedia". www.hindupedia.com. 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b Karl H. Potter (2002), Presuppositions of India's Philosophies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120807792, pp. 1-29

- ^ a b Roderick Hindery, "Hindu Ethics in the Ramayana", The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall, 1976), pp. 299

- ^ See verses at 2.30, 4.1, 6.1, 6.83 for example; Abridged Verse 4.1: "Sita invades my entire being and my love is entirely centered on her; Without that lady of lovely eyelashes, beautiful looks, and gentle speech, I cannot survive, O Saumitri."; for peer reviewed source, see Hindery, The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall, 1976), pp 299-300

- ^ Benjamin Khan (1965), The concept of Dharma in Valmiki Ramayana, Delhi, ISBN 978-8121501347

- ^ Gavin Flood (1996), The meaning and context of the Purusarthas, in Julius Lipner (Editor), The Fruits of Our Desiring, ISBN 978-1896209302, pp 11-13

- ^ Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ Gavin Flood (1996), The meaning and context of the Purusarthas, in Julius Lipner (Editor) - The Fruits of Our Desiring, ISBN 978-1896209302, pp 16-21

- ^ The Hindu Kama Shastra Society (1925), The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, University of Toronto Archives, pp. 9-10

- ^ a b The Hindu Kama Shastra Society (1925), The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, University of Toronto Archives, Chapter 2, pp 8-11; pp 172

- ^ Jacob Levy (2010), Kama sense marketing, iUniverse, ISBN 978-1440195563, see Introduction

- ^ Alain Daniélou, The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text, ISBN 978-0892815258

- ^ The Hindu Kama Shastra Society (1925), Answer 4, The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, University of Toronto Archives, pp. 11

- ^ Bullough and Bullough (1994), Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0824079727, pp 516

- ^ Gary Kraftsow, Yoga for Transformation - ancient teachings and practices for healing body, mind and heart, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-019629-0, pp 11-15

- ^ C. Ramanathan, Ethics in the Ramayana, in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization (Editor: R. Prasad), Volume 12, Part 1, ISBN 978-8180695445, pp 84-85

- ^ P.V. Kane (1941), History of Dharmashastra, Volume 2, Part 1, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, pp. 8-9

- ^ Kama Archived 2015-06-07 at the Wayback Machine in Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago, 2009

- ^ Coulter and Turner, Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Francis & Taylor, ISBN 978-1135963903, pp 258-259

- ^ Śaṅkarakavi, Fabrizia Baldissera Śāradātilakabhāṇaḥ 1980 "Sammohanam , infatuation , name of the fifth arrow of Kāma , the most dangerous because it leads to the ultimate stage of love folly"

- ^ William Joseph Wilkins (193), Hindu mythology, Vedic and Puranic, Thacker & Spink, Indiana University Archives, pp 268

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ See, for instance, Dvedhavitakka Sutta (MN 19) (Thanissaro, 1997a). Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See, for instance, Khantipalo (1995). Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dhammika Sutta: Dhammika". www.accesstoinsight.org.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ "Bahuvedaniya Sutta: The Many Kinds of Feeling". www.accesstoinsight.org. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty pleasures: kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. Uppsala: Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-3025-1.

- ^ Ali, Daud (2011). "Rethinking the History of the "Kāma" World in Early India". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 39 (1): 1–13. ISSN 0022-1791.

Sources

- Fiorucci, Anthony (2023). Guilty Pleasures: Kāma in ancient India and the Pali Vinaya. PhD thesis: Uppsala University. ISBN: 978-91-506-3025-1.

- Ireland, John D. (trans.) (1983). Dhammika Sutta: Dhammika (excerpt) (Sn 2.14). Retrieved 5 Jul 2007 from "Access to Insight" at Dhammika Sutta: Dhammika.

- Khantipalo, Bhikkhu (1982, 1995). Lay Buddhist Practice: The Shrine Room, Uposatha Day, Rains Residence (The Wheel No. 206/207). Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. Retrieved 5 Jul 2007 from "Access to Insight" at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/khantipalo/wheel206.html.

- Sri Lanka Buddha Jayanti Tipitaka Series (n.d.) (SLTP). Pañcaṅgikavaggo (AN 5.1.3.8, in Pali). Retrieved 3 Jul 2007 from "MettaNet-Lanka" at 5:3 Pancangikavaggo - Pali.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1997a). Dvedhavitakka Sutta: Two Sorts of Thinking (MN 19). Retrieved 3 Jul 2007 from "Access to Insight" at Dvedhavitakka Sutta: Two Sorts of Thinking.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (trans.) (1997b). Samadhanga Sutta: The Factors of Concentration (AN 5.28). Retrieved 3 Jul 2007 from "Access to Insight" at Samadhanga Sutta: The Factors of Concentration.

External links

- About.com page

- Kamadeva's holy sacrifice (archived 22 March 2018)