Statistical Genetics Wiki

Contents

| Somite | |

|---|---|

Transverse section of half of a chick embryo of forty-five hours' incubation. The dorsal (back) surface of the embryo is towards the top of this page, while the ventral (front) surface is towards the bottom. | |

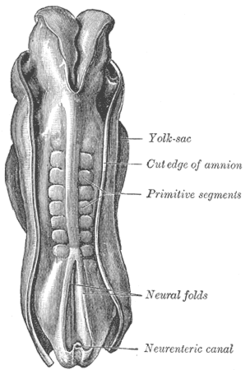

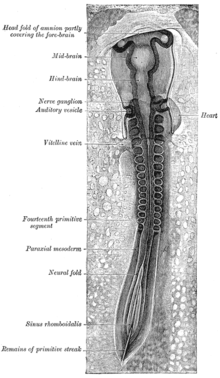

Dorsum of human embryo, 2.11 mm in length. (The older term primitive segments is used to identify the somites.) | |

| Details | |

| Carnegie stage | 9 |

| Days | 20[1] |

| Precursor | Paraxial mesoderm |

| Gives rise to | Dermatome, myotome, sclerotome, syndetome |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | somitus |

| MeSH | D019170 |

| TE | E5.0.2.2.2.0.3 |

| FMA | 85522 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The somites (outdated term: primitive segments) are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites subdivide into the dermatomes, myotomes, sclerotomes and syndetomes that give rise to the vertebrae of the vertebral column, rib cage, part of the occipital bone, skeletal muscle, cartilage, tendons, and skin (of the back).[2]

The word somite is sometimes also used in place of the word metamere. In this definition, the somite is a homologously-paired structure in an animal body plan, such as is visible in annelids and arthropods.[3]

Development

The mesoderm forms at the same time as the other two germ layers, the ectoderm and endoderm. The mesoderm at either side of the neural tube is called paraxial mesoderm. It is distinct from the mesoderm underneath the neural tube, which is called the chordamesoderm that becomes the notochord. The paraxial mesoderm is initially called the "segmental plate" in the chick embryo or the "unsegmented mesoderm" in other vertebrates. As the primitive streak regresses and neural folds gather (to eventually become the neural tube), the paraxial mesoderm separates into blocks called somites.[4]

Formation

The pre-somitic mesoderm commits to the somitic fate before mesoderm becomes capable of forming somites. The cells within each somite are specified based on their location within the somite. Additionally, they retain the ability to become any kind of somite-derived structure until relatively late in the process of somitogenesis.[4]

The development of the somites depends on a clock mechanism as described by the clock and wavefront model. In one description of the model, oscillating Notch and Wnt signals provide the clock. The wave is a gradient of the fibroblast growth factor protein that is rostral to caudal (nose to tail gradient). Somites form one after the other down the length of the embryo from the head to the tail, with each new somite forming on the caudal (tail) side of the previous one.[5][6]

The timing of the interval is not universal. Different species have different interval timing. In the chick embryo, somites are formed every 90 minutes. In the mouse the interval is 2 hours.[7]

For some species, the number of somites may be used to determine the stage of embryonic development more reliably than the number of hours post-fertilization because rate of development can be affected by temperature or other environmental factors. The somites appear on both sides of the neural tube simultaneously. Experimental manipulation of the developing somites will not alter the rostral/caudal orientation of the somites, as the cell fates have been determined prior to somitogenesis. Somite formation can be induced by Noggin-secreting cells. The number of somites is species dependent and independent of embryo size (for example, if modified via surgery or genetic engineering). Chicken embryos have 50 somites; mice have 65, while snakes have 500.[4][8]

As cells within the paraxial mesoderm begin to come together, they are termed somitomeres, indicating a lack of complete separation between segments. The outer cells undergo a mesenchymal–epithelial transition to form an epithelium around each somite. The inner cells remain as mesenchyme.

Notch signalling

The Notch system, as part of the clock and wavefront model, forms the boundaries of the somites. DLL1 and DLL3 are Notch ligands, mutations of which cause various defects. Notch regulates HES1, which sets up the caudal half of the somite. Notch activation turns on LFNG which in turn inhibits the Notch receptor. Notch activation also turns on the HES1 gene which inactivates LFNG, re-enabling the Notch receptor, and thus accounting for the oscillating clock model. MESP2 induces the EPHA4 gene, which causes repulsive interaction that separates somites by causing segmentation. EPHA4 is restricted to the boundaries of somites. EPHB2 is also important for boundaries.

Mesenchymal-epithelial transition

Fibronectin and N-cadherin are key to the mesenchymal–epithelial transition process in the developing embryo. The process is probably regulated by paraxis and MESP2. In turn, MESP2 is regulated by Notch signaling. Paraxis is regulated by processes involving the cytoskeleton.

Specification

The Hox genes specify somites as a whole based on their position along the anterior-posterior axis through specifying the pre-somitic mesoderm before somitogenesis occurs. After somites are made, their identity as a whole has already been determined, as is shown by the fact that transplantation of somites from one region to a completely different region results in the formation of structures usually observed in the original region. In contrast, the cells within each somite retain plasticity (the ability to form any kind of structure) until relatively late in somitic development.[4]

Derivatives

In the developing vertebrate embryo, somites split to form dermatomes, skeletal muscle (myotomes), tendons and cartilage (syndetomes)[9] and bone (sclerotomes).

Because the sclerotome differentiates before the dermatome and the myotome, the term dermomyotome refers to the combined dermatome and myotome before they separate out.[10]

Dermatome

The dermatome is the dorsal portion of the paraxial mesoderm somite which gives rise to the skin (dermis). In the human embryo, it arises in the third week of embryogenesis.[2] It is formed when a dermomyotome (the remaining part of the somite left when the sclerotome migrates), splits to form the dermatome and the myotome.[2] The dermatomes contribute to the skin, fat and connective tissue of the neck and of the trunk, though most of the skin is derived from lateral plate mesoderm.[2]

Myotome

The myotome is that part of a somite that forms the muscles of the animal.[2] Each myotome divides into an epaxial part (epimere), at the back, and a hypaxial part (hypomere) at the front.[2] The myoblasts from the hypaxial division form the muscles of the thoracic and anterior abdominal walls. The epaxial muscle mass loses its segmental character to form the extensor muscles of the neck and trunk of mammals.

In fishes, salamanders, caecilians, and reptiles, the body musculature remains segmented as in the embryo, though it often becomes folded and overlapping, with epaxial and hypaxial masses divided into several distinct muscle groups.[citation needed]

Sclerotome

The sclerotome (or cutis plate) forms the vertebrae and the rib cartilage and part of the occipital bone; the myotome forms the musculature of the back, the ribs and the limbs; the syndetome forms the tendons and the dermatome forms the skin on the back. In addition, the somites specify the migration paths of neural crest cells and the axons of spinal nerves. From their initial location within the somite, the sclerotome cells migrate medially towards the notochord. These cells meet the sclerotome cells from the other side to form the vertebral body. The lower half of one sclerotome fuses with the upper half of the adjacent one to form each vertebral body.[11] From this vertebral body, sclerotome cells move dorsally and surround the developing spinal cord, forming the vertebral arch. Other cells move distally to the costal processes of thoracic vertebrae to form the ribs.[11]

In arthropods

In crustacean development, a somite is a segment of the hypothetical primitive crustacean body plan. In current crustaceans, several of those somites may be fused.[12][13]

See also

References

- ^ Cuschieri, Alfred. "The Third Week Of Life". University of Malta. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 53–86. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- ^ "Metamere". Dictionary and Thesaurus-Merriam-Webster Online. Merriam-Webster. 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, S.F. (2010). Developmental Biology (9th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. pp. 413–415. ISBN 978-0-87893-384-6.

- ^ Baker, R. E.; Schnell, S.; Maini, P. K. (2006). "A clock and wavefront mechanism for somite formation". Developmental Biology. 293 (1): 116–126. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.018. PMID 16546158.

- ^ Goldbeter, A.; Pourquié, O. (2008). "Modeling the segmentation clock as a network of coupled oscillations in the Notch, Wnt and FGF signaling pathways" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 252 (3): 574–585. Bibcode:2008JThBi.252..574G. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.01.006. PMID 18308339 – via Université libre de Bruxelles.

- ^ Wahi, Kanu (2016). "The many roles of Notch signaling during vertebrate somitogenesis". Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 49: 68–75. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.010. PMID 25483003. S2CID 10822545.

- ^ Gomez, C; et al. (2008). "Control of segment number in vertebrate embryos". Nature. 454 (7202): 335–339. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..335G. doi:10.1038/nature07020. PMID 18563087. S2CID 4373389.

- ^ Brent AE, Schweitzer R, Tabin CJ (April 2003). "A somitic compartment of tendon progenitors". Cell. 113 (2): 235–48. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00268-X. PMID 12705871. S2CID 16291509.

- ^ "Embryo Images". University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ a b Walker, Warren F., Jr. (1987) Functional Anatomy of the Vertebrate San Francisco: Saunders College Publishing.

- ^ Ferrari, Frank D.; Fornshell, John; Vagelli, Alejandro A.; Ivanenko, V. N.; Dahms, Hans-Uwe (2011). "Early Post-Embryonic Development of Marine Chelicerates and Crustaceans with a Nauplius" (PDF). Crustaceana. 84 (7): 869–893. ISSN 0011-216X.

- ^ Manning, Raymond (1998). "A new genus and species of pinnotherid crab (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura) from Indonesia". Zoosystema. 20 (2): 357–362.