LIMSwiki

Contents

| Spirula Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

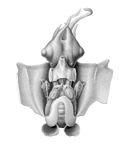

| Dorsal view of female | |

| |

| Ventral view of female (chromatophores of mantle missing) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Spirulida |

| Family: | Spirulidae Owen, 1836 |

| Genus: | Spirula Lamarck, 1799 |

| Species: | S. spirula

|

| Binomial name | |

| Spirula spirula | |

| Synonyms | |

Spirula spirula is a species of deep-water squid-like cephalopod mollusk. It is the only extant member of the genus Spirula, the family Spirulidae, and the order Spirulida. Because of the shape of its internal shell, it is commonly known as the ram's horn squid[3] or the little post horn squid. Because the live animal has a light-emitting organ, it is also sometimes known as the tail-light squid.

Live specimens of this cephalopod are very rarely seen because it is a deep-ocean dweller. The small internal shell of the species is, however, quite a familiar object to many beachcombers. The shell of Spirula is extremely light in weight, very buoyant, and surprisingly durable; it very commonly floats ashore onto tropical beaches (and sometimes even temperate beaches) all over the world. This seashell is known to shell collectors as the ram's horn shell or simply as Spirula.

-

Side view of a Spirula shell

Taxonomy

Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus described Nautilus spirula Linnaeus, 1758 in his book Systema Naturae.[4] In 1799, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck described the genus Spirula and transferred this species to it, and Spirula spirula is the name still used today for the ram's horn squid.[5][6] S. spirula is the only species in the monotypic genus Spirula. A morphometric study published in 2010 showed that shell characteristics of S. spirula vary with geography, but no subspecies or additional species were proposed.[7]

Description

S. spirula has a squid-like body between 35 mm and 45 mm long. It is a decapod, with eight arms and two longer tentacles, all with suckers. The arms and tentacles can all be withdrawn completely into the mantle.

The species lacks a radula[8]: 110 [9]: 26 (or, at most, has a vestigial radula).[10]

Shell

The most distinctive feature of this species is its buoyancy organ, an internal, chambered, endogastrically coiled shell in the shape of an open planispiral (a flat spiral wherein the coils do not touch each other), and consisting of two prismatic layers. The shell functions to osmotically control buoyancy.[10] Unlike the nautilus, which exchange air and liquid only in the three most adoral chambers (the remaining chambers always being gas-filled), spirula can bring cameral fluid into all of their chambers.[11] Another trait is that it is mineralized, a feature only seen in cuttlefish and the nautilus amongst extant species of cephalopods.[12]

The siphuncle is marginal, on the inner surface of the spiral.[13]

Behaviour

S. spirula is capable of emitting a green light from a photophore located at the tip of its mantle, between the ear-shaped fins.[10] Evidently this seems as a counter-illumination strategy, as in situ observations have captured footage of animals in a vertical stance, with photophore pointing downward and head up.[14]

Habitat and distribution

By day, Spirula lives in the deep oceans, reaching depths of 1,000 m. At night, it rises to 100–300 m.[15][5] Its preferred temperature is around 10 °C, and it tends to live around oceanic islands, near the continental shelf.[10]

Most sources cite this species as tropical and they are observed to be plentiful in the subtropical seas around the Canary Islands. Shells are regularly found along the western coasts of South Africa. In 2022, records of the species have also been confirmed in the Arabian Sea.[16] However, significant quantities of shells from dead spirula are washed ashore even in temperate regions, such as coasts of New Zealand. Because of the great buoyancy of the shells, these may possibly have been carried long distances by ocean currents.

Much of the organism's life history has not been observed; for instance, they are thought to spawn in winter in deeper water, yet no spawnlings have been directly seen. They must occasionally venture into the upper 10 m of the sea, for they are sometimes found in albatross guts.[17]

The species was observed for the first time in its natural habitat in 2020, when an ROV of the Schmidt Ocean Institute recorded it in the depths near the northern Great Barrier Reef.[14][18]

Evolutionary relationships

The order Spirulida also contains two extinct suborders: Groenlandibelina (including extinct families Groenlandibelidae and Adygeyidae), and Belopterina (including extinct families Belemnoseidae and Belopteridae).

Spirula is likely the closest living relative of the extinct belemnites and aulacocerids. These three groups as a unit are closely related to the cuttlefish, as well as to the true squids.

See also

References

- ^ Hayward, B.W. (1977). "Spirula (Sepioidea: Cephalopoda) from the Lower Miocene of Kaipara Harbour, New Zealand (note)" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 19: 145–147. doi:10.1080/00288306.1976.10423557.

- ^ Barratt, I. & Allcock, L. (2012). Spirula spirula. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2.

- ^ Norman, M. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. Hackenheim, ConchBooks.

- ^ Linné, Carl von (1758). Systema naturae, per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. v. 1, pt. 2 (Ed. 13. ed.). Vindobonae [Vienna]: Typis Ioannis Thomae. p. 1163.

- ^ a b "Critter of the week: Spirula spirula | NIWA". niwa.co.nz. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1799). Mémoires de la Société d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris (in French). Vol. 1. p. 80.

- ^ Neige, Pascal; Warnke, Kerstin (2010). "Just how many species of Spirula are there? A morphometric approach". Cephalopods - Present and Past: 77–84.

- ^ Nixon, M. (1985), "The buccal mass of fossil and recent Cephalopoda", in Wilbur, Karl M. (ed.), The Mollusca, New York: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-728702-7

- ^ Landman, Neil H.; Tanabe, Kazushige; Davis, Richard Arnold (1996). Ammonoid Paleobiology. ISBN 978-0-306-45222-2.

- ^ a b c d Warnke, K.; Keupp, H. (2005). "Spirula – a window to the embryonic development of ammonoids? Morphological and molecular indications for a palaeontological hypothesis" (PDF). Facies. 51 (1–4): 60. doi:10.1007/s10347-005-0054-9. S2CID 85026080.

- ^ Evolution of the Ammonoids

- ^ Lemanis, R.; Korn, D.; Zachow, S; Rybacki, E.; Hoffmann, R. (2016). "The evolution and development of cephalopod chambers and their shape". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0151404. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1151404L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151404. PMC 4786199. PMID 26963712.

- ^ "Spirula spirula". Tree of Life (tolweb.org).

- ^ a b c Lindsay, Dhugal; Hunt, James; McNeil, Mardi; Beaman, Robin; Vecchione, Michael (27 November 2020). "The first in situ observation of the Ram's Horn squid Spirula spirula turns "common knowledge" upside down". Diversity. 12 (449): 449. doi:10.3390/d12120449.

- ^ Clarke, M.R. (2009). "Cephalopoda collected on the SOND Cruise". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 49 (4): 961–976. doi:10.1017/S0025315400038042. S2CID 86329056.

- ^ Sajikumar, K.K; Rajeeshkumar, M.P; Vellathi, Venkatesan (June 2022). "Rediscovery of Ram's horn squid, Spirula spirula (Cephalopoda: Spirulidae), from the Arabian Sea".

- ^ Price, G.D.; Twitchett, R.J.; Smale, C.; Marks, V. (2009). "Isotopic analysis of the life history of the enigmatic squid Spirula spirula, with implications for studies of fossil Cephalopods". PALAIOS. 24 (5): 273–279. Bibcode:2009Palai..24..273P. doi:10.2110/palo.2008.p08-067r. S2CID 131523262.

- ^ Fox, Alex (3 November 2020). "See strange squid filmed in the wild for the first time". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

External links

- "Spirula Spirula". Tree of Life web project.

- "Spirulidae forum". TONMO.com. Archived from the original on 2006-03-16 – via Internet Archive (archive.org).