LIMSwiki

Contents

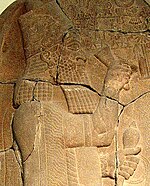

| Madyes | |

|---|---|

| King of the Scythians | |

| Reign | c. 658/9 - 625 BCE |

| Predecessor | Bartatua |

| Successor | Unknown |

| Died | 625 BCE |

| Median | Mādava |

| Dynasty | Bartatua's dynasty |

| Father | Bartatua |

| Mother | Šērūʾa-ēṭirat (?) |

| Religion | Scythian religion Ancient Mesopotamian religion (?) |

Madyes was a Scythian king who ruled during the period of the Scythian presence in West Asia in the 7th century BCE.

Madyes was the son of the Scythian king Bartatua and the Assyrian princess Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, and, as an ally of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which was then the superpower of West Asia and whose king Ashurbanipal was his uncle, he brought Scythian power to its peak in West Asia.

After the Neo-Assyrian Empire started unravelling, Madyes was assassinated by the Median king Cyaxares, who expelled the Scythians from West Asia.

Name

The name Madyes is the Latinised form of Maduēs (Ancient Greek: Μαδυης),[1] which is itself the Ancient Greek form of an Old Iranic name.[2]

Iranologist had initially suggested that the original form of Madyes's name was Scythian *Madava, meaning “mead,” derived from a term for honey, *madu-.[3][4][2]

However, the Iranic sound /d/ had evolved into /δ/ in Proto-Scythian, and later evolved into /l/ in Scythian, due to which the Proto-Iranic term *madu- had become *malu- in Scythian,[5] hence why the scholar Mikhail Bukharin considered the derivation of Madyes from *madu- as unlikely, and, noting that the name of Madyes was transmitted through Persian sources to the Greek authors who recorded it, proposed that the name Μαδυης instead originated from a Western Iranic form *Mādava-, meaning “Median.”[6]

Historical background

In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, a significant movement of the nomads of the Eurasian steppe brought the Scythians into Southwest Asia. This movement started when another nomadic Iranic tribe closely related to the Scythians, either the Massagetae[7] or the Issedones,[8] migrated westwards, forcing the Early Scythians of the to the west across the Araxes river,[9] following which the Scythians moved into the Caspian Steppe from where they displaced the Cimmerians.[9]

Under Scythian pressure, the Cimmerians migrated to the south along the coast of the Black Sea and reached Anatolia, and the Scythians in turn later expanded to the south, following the coast of the Caspian Sea and arrived in the steppes in the Northern Caucasus, from where they expanded into the region of present-day Azerbaijan, where they settled and turned eastern Transcaucasia into their centre of operations in West Asia until the early 6th century BCE,[10][11][12][13] with this presence in West Asia being an extension of the Scythian kingdom of the steppes.[14] During this period, the Scythian kings' headquarters were located in the steppes to the north of Caucasus, and contact with the civilisation of West Asia would have an important influence on the formation of Scythian culture.[7]

Life and reign

Background

Madyes was the son of the previous Scythian king, Bartatua, and possibly the grandson of Bartatua's predecessor, Išpakaia.[15] Išpakaia had been an enemy of the then superpower in West Asia, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was killed in battle against the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, after which Bartatua became the king of the Scythians and instead sought to ally with the Assyrians.[16]

The name of Madyes's mother is not recorded, but, since Bartatua had asked in marriage the hand of the Assyrian princess Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, who was the daughter of Esarhaddon and the sister of his successors Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin, and there was a close alliance between the Scythians and Assyria under the reigns of Bartatua and Madyes, this suggests that the Assyrian priests did approve of this marriage between a daughter of an Assyrian king and a nomadic lord, which had never happened before in Assyrian history; the Scythians were thus brought into a marital alliance with Assyria, and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat was likely the mother of Bartatua's son Madyes.[17][18][19][20][21]

Bartatua's marriage to Šērūʾa-ēṭirat required that he would pledge allegiance to Assyria as a vassal, and in accordance to Assyrian law, the territories ruled by him would be his fief granted by the Assyrian king, which made the Scythian presence in West Asia a nominal extension of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[16] Under this arrangement, the power of the Scythians in West Asia heavily depended on their cooperation with the Assyrian Empire;[22] henceforth, the Scythians remained allies of the Assyrian Empire.[16] Around this time, the Urartian king Rusa II might also have enlisted Scythian troops to guard his western borderlands.[18]

The marital alliance between the Scythian king and the Assyrian ruling dynasty, as well as the proximity of the Scythians with Mannai and Urartu, placed the Scythians under the strong influence of Assyrian culture.[12] After Bartatua's death, Madyes succeeded him.[16]

Conquest of Media

When, following a period of Assyrian decline over the course of the 650s BCE, Esarhaddon's other son, Shamash-shum-ukin, who had succeeded him as the king of Babylon, revolted against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BCE, the Medes supported him, and Madyes helped Ashurbanipal suppress the revolt externally by invading the Medes. The Median king Phraortes was killed in battle, either against the Assyrians or against Madyes himself, who then imposed Scythian hegemony over Media for twenty-eight years on behalf of the Assyrians, thus starting a period which Greek authors called the “Scythian rule over Asia.”[23][13][12]

Madyes soon expanded the Scythian hegemony to the state of Urartu as well, with Media, Mannai and Urartu all continuing to exist as kingdoms under Scythian suzerainty.[23]

Defeat of the Cimmerians

During the 7th century BCE, the bulk of the Cimmerians were operating in Anatolia, where they constituted a threat against the Scythians’ Assyrian allies, who since 669 BCE were ruled by Madyes's uncle, that is Esarhaddon's son and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat's brother, Ashurbanipal. Assyrian records in 657 BCE might have referred to a threat against or a conquest of the western possessions of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in Syria,[24][25] and these Cimmerian aggressions worried Ashurbanipal about the security of his empire's north-west border.[26] By 657 BCE the Assyrian divinatory records were calling the Cimmerian king Tugdammi by the title of šar-kiššati ("King of the Universe"), which could normally belong only to the Neo-Assyrian King: thus, Tugdammi's successes against Assyria meant that he had become recognised in ancient West Asia as equally powerful as Ashurbanipal, and the kingship over the Universe, which rightfully belonged to the Assyrian king, had been usurped by the Cimmerians and had to be won back by Assyria. This situation continued throughout the rest of the 650s BCE and the early 640s BCE.[24]

In 644 BCE, the Cimmerians, led by Tugdammi, attacked the kingdom of Lydia, defeated the Lydians and captured the Lydian capital, Sardis; the Lydian king Gyges died during this attack.[27][26][28] After sacking Sardis, Tugdammi led the Cimmerians into invading the Greek city-states of Ionia and Aeolis on the western coast of Anatolia.[24] After this attack on Lydia and the Asian Greek cities, around 640 BCE the Cimmerians moved to Cilicia on the north-west border of the Neo-Assyrian empire, where, after Tugdammi faced a revolt against himself, he allied with Assyria and acknowledged Assyrian overlordship, and sent tribute to Ashurbanipal, to whom he swore an oath. Tugdammi soon broke this oath and attacked the Neo-Assyrian Empire again, but he fell ill and died in 640 BCE, and was succeeded by his son Sandakšatru.[27][26]

In 637 BCE, the Thracian Treres tribe who had migrated across the Thracian Bosporos and invaded Anatolia,[29] under their king Kōbos and in alliance with Sandakšatru's Cimmerians and the Lycians, attacked Lydia during the seventh year of the reign of Gyges's son Ardys.[27] They defeated the Lydians and captured their capital of Sardis except for its citadel, and Ardys might have been killed in this attack.[30] Ardys's son and successor, Sadyattes, might possibly also have been killed in another Cimmerian attack on Lydia in 635 BCE.[30]

Soon after 635 BCE, with Assyrian approval[31] and in alliance with the Lydians,[32] the Scythians under Madyes entered Anatolia, expelled the Treres from Asia Minor, and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia.[13][27] This final defeat of the Cimmerians was carried out by the joint forces of Madyes, whom Strabo credits with expelling the Treres and Cimmerians from Asia Minor, and of Sadyattes’s son, Ardys’s grandson, and Gyges's great-grandson, the king Alyattes of Lydia, whom Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Polyaenus claim finally defeated the Cimmerians.[24][33]

In Polyaenus' account of the defeat of the Cimmerians, he claimed that Alyattes used "war dogs" to expel them from Asia Minor, with the term "war dogs" being a Greek folkloric reinterpretation of young Scythian warriors who, following the Indo-European passage rite of the [[Kóryos|kóryos]], would ritually take on the role of wolf- or dog-warriors.[34]

Scythian power in West Asia thus reached its peak under Madyes, with the territories ruled by the Scythians extending from the Halys river in Anatolia in the west to the Caspian Sea and the eastern borders of Media in the east, and from Transcaucasia in the north to the northern borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the south.[13][35]

Revolt of Media and death

By the 620s BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire began unravelling after the death of Ashurbanipal in 631 BCE: in addition to internal instability within Assyria itself, Babylon revolted against the Assyrians in 626 BCE under the leadership of Nabopolassar.[36] The next year, in 625 BCE, Cyaxares, the son of Phraortes and his successor to the Median kingship, overthrew the Scythian yoke over the Medes by inviting the Scythian rulers to a banquet and then murdering them all, including Madyes, after getting them drunk.[37][38][12]

Aftermath

Madyes's relationship with the Scythian kings after him and the identity of his successor are both unknown, although shortly after his assassination, some time between 623 and 616 BCE, the Scythians took advantage of the power vacuum created by the crumbling of the power of their former Assyrian allies and overran the Levant and reached as far south as Palestine till the borders of Egypt,[14][39] where their advance was stopped by the marshes of the Nile Delta, after which the pharaoh Psamtik I met them and convinced them to turn back by offering them gifts.[40][13] The Scythians retreated by passing through Askalon largely without any incident, although some stragglers looted the temple of Astarte in the city, which was considered to be the most ancient of all temples to that goddess, as a result of which the perpetrators of this sacrilege and their descendants were allegedly cursed by Astarte with a “female disease,” due to which they became a class of transvestite diviners called the Anarya (meaning “unmanly” in Scythian[14]).[13]

According to Babylonian records, around 615 BCE the Scythians were operating as allies of Cyaxares and the Medes in their war against Assyria.[22] The Scythians were finally expelled from West Asia by the Medes in the 600s BCE, after which they retreated into the Pontic Steppe.[22]

Legacy

The Graeco-Roman authors conflated Madyes with his predecessors and successors into a single figure by claiming that it was Madyes himself who led the Scythians from Central Asia into chasing the Cimmerians out of their homeland and then defeating the Medes and the legendary Egyptian king Sesostris and imposing their rule over Asia for many years before returning to Scythia. Later Graeco-Roman authors named this Scythian king as Idanthyrsos or Tanausis, although this Idanthyrsos is a legendary figure separate from the later historical Scythian king Idanthyrsus, from whom the Graeco-Romans derived merely his name.[41][11][42]

References

- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Madyes

- ^ a b Schmitt 2003.

- ^ Tokhtasyev 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Schmitt 2018: "*madu- “intoxicating drink” (in Madýēs)"

- ^ Vitchak 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Bukharin 2011, p. 61-64.

- ^ a b Olbrycht 2000b.

- ^ Olbrycht 2000a.

- ^ a b Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 553.

- ^ Ivantchik 1993a, p. 127-154.

- ^ a b Diakonoff 1985, p. 97.

- ^ a b c d Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 560-590.

- ^ a b c d e f Phillips 1972.

- ^ a b c Ivantchik 2018.

- ^ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 564.

- ^ a b c d Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 564-565.

- ^ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 566-567.

- ^ a b Barnett 1991, pp. 356–365.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 89-109.

- ^ Ivantchik 2018: "In approximately 672 BCE the Scythian king Partatua (Protothýēs of Hdt., 1.103) asked for the hand of the daughter of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, promising to conclude a treaty of alliance with Assyria. It is probable that this marriage took place and the alliance also came into being (SAA IV, no. 20; Ivantchik, 1993, pp. 93-94; 205-9)."

- ^ Bukharin 2011: "С одной стороны, Мадий, вероятно, полуассириец, даже будучи «этническим» полускифом (его предшественник и, вероятно, отец, ‒ царь скифов Прототий, женой которого была дочь ассирийского царя Ассархаддона)" [On the one hand, Madyes is probably a half-Assyrian, even being an “ethnic” half-Scythian (his predecessor and, probably, father, is the king of the Scythians Protothyes, whose wife was the daughter of the Assyrian king Essarhaddon)]

- ^ a b c Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 567.

- ^ a b Diakonoff 1985, p. 117-118.

- ^ a b c d Ivantchik 1993a, p. 95-125.

- ^ Brinkman 1991.

- ^ a b c Tokhtas’ev 1991.

- ^ a b c d Spalinger 1978a.

- ^ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 559.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 94-55.

- ^ a b Dale 2015.

- ^ Grousset 1970, p. 9: A Scythian army, acting in conformity with Assyrian policy, entered Pontis to crush the last of the Cimmerians.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 126.

- ^ Ivantchik 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Ivantchik 1993b.

- ^ Vaggione 1973.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 110-119.

- ^ Diakonoff 1993.

- ^ Diakonoff 1985, p. 119.

- ^ Hawkins 1991.

- ^ Spalinger 1978b.

- ^ Spalinger 1978b, p. 54.

- ^ Ivantchik 1999.

Sources

- Barnett, R. D. (1991). "Urartu". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 314–371. ISBN 978-1-139-05428-7.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1991). "Babylonia in the Shadow of Assyria". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Bukharin, Mikhail Dmitrievich [in Russian] (2011). "Колаксай и его братья (античная традиция о происхождении царской власти у скифов" [Kolaxais and his Brothers (Classical Tradition on the Origin of the Royal Power of the Scythians)]. Аристей: вестник классической филологии и античной истории [Aristaeus: Journal of Classical Philology and Ancient History] (in Russian). 3: 20–80. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- Dale, Alexander (2015). "WALWET and KUKALIM: Lydian coin legends, dynastic succession, and the chronology of Mermnad kings". Kadmos. 54: 151–166. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2015-0008. S2CID 165043567. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1985). "Media". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1993). "Cyaxares". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Translated by Walford, Naomi. New Brunswick, United States: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-813-51304-1.

- Hawkins, J. D. (1991). "The Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 372–441. ISBN 978-1-139-05428-7.

- Ivantchik, Askold (1993a). Les Cimmériens au Proche-Orient [The Cimmerians in the Near East] (PDF) (in French). Fribourg, Switzerland; Göttingen, Germany: Editions Universitaires (Switzerland); Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (Germany). ISBN 978-3-727-80876-0.

- Ivantchik, Askold (1993b). "LES GUERRIERS-CHIENS: Loups-garous et invasions scythes en Asie Mineure" [THE DOG WARRIORS: Werewolves and Scythian invasions in Asia Minor]. Revue de l'histoire des religions [Review of the History of Religions]. 210 (3): 305–330. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- Ivantchik, Askold (1999). "The Scythian 'Rule Over Asia': the Classical Tradition and the Historical Reality". In Tsetskhladze, G.R. (ed.). Ancient Greeks West and East. Leiden, Netherlands; Boston, United States: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11190-5.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2006). Aruz, Joan; Farkas, Ann; Fino, Elisabetta Valtz (eds.). The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Perspectives on the Steppe Nomads of the Ancient World. New Haven, Connecticut, United States; New York City, United States; London, United Kingdom: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Yale University Press. p. 146-153. ISBN 978-1-588-39205-3.

- Ivantchik, Askold (2018). "SCYTHIANS". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000a). "The Cimmerian Problem Re-Examined: the Evidence of the Classical Sources". In Pstrusińska, Jadwiga [in Polish]; Fear, Andrew (eds.). Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 71–100. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2000b). "Remarks on the Presence of Iranian Peoples in Europe and Their Asiatic Relations". In Pstrusińska, Jadwiga [in Polish]; Fear, Andrew (eds.). Collectanea Celto-Asiatica Cracoviensia. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. pp. 101–140. ISBN 978-8-371-88337-8.

- Phillips, E. D. (1972). "The Scythian Domination in Western Asia: Its Record in History, Scripture and Archaeology". World Archaeology. 4 (2): 129–138. doi:10.1080/00438243.1972.9979527. JSTOR 123971. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2003). "Die skythischen Personennamen bei Herodot" [Scythian Personal Names in Herodotus] (PDF). Annali dell'Università degli Studi di Napoli l'Orientale [Annals of the University of Naples "L'Orientale"] (in German). 63. Naples, Italy: Università degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale": 1–31.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2018). "SCYTHIAN LANGUAGE". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- Spalinger, Anthony J. (1978a). "The Date of the Death of Gyges and Its Historical Implications". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 98 (4): 400–409. doi:10.2307/599752. JSTOR 599752. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- Spalinger, Anthony (1978b). "Psammetichus, King of Egypt: II". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 15: 49–57. doi:10.2307/40000130. JSTOR 40000130. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz; Taylor, T. F. (1991). "The Scythians". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–590. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Tokhtas’ev, Sergei R. [in Russian] (1991). "Cimmerians". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers.

- Tokhtasyev, Sergey [in Russian] (2005). "Проблема Скифского Языка в Современной Науке" [The Problem of the Scythian Language in Contemporary Studies]. In Cojocaru, Victor (ed.). Ethnic Contacts and Cultural Exchanges North and West of the Black Sea from the Greek Colonization to the Ottoman Conquest ; [Proceedings of the International Symposium Ethnic contacts and Cultural Exchanges North and West of the Black Sea, Iaşi, June 12-17, 2005] (in Russian). Iași, Romania: Trinitas. pp. 59–108. ISBN 978-9-737-83450-8.

- Vaggione, Richard P. (1973). "Over All Asia? The Extent of the Scythian Domination in Herodotus". Journal of Biblical Literature. 92 (4): 523–530. doi:10.2307/3263121. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Vitchak, K. T. (1999). "Скифский язык: опыт описания" [The Scythian Language: Attempt at Description]. Вопросы языкознания (in Russian). 5: 50–59. Retrieved 27 August 2022.