LIMSwiki

Contents

| Broadcast area | Greater St. Louis |

|---|---|

| Frequency | 1430 kHz |

| Programming | |

| Format | Defunct |

| Ownership | |

| Owner |

|

| Operator | Insane Broadcasting Company |

| KQQZ, KFTK, WQQW | |

| History | |

First air date | April 5, 1922 |

Last air date | April 2020 |

Former call signs | WEB (1922–25) WIL (1925–91) WRTH (1991–2005) WIL (2005–08) |

| Technical information | |

| Facility ID | 72391 |

| Class | B |

| Power | 50,000 watts (day) 5,000 watts (night) |

Transmitter coordinates | 38°32′09″N 90°11′26″W / 38.53583°N 90.19056°W |

KZQZ was a commercial radio station that was licensed to serve St. Louis, Missouri at 1430 AM, and broadcast from 1922 to 2020. As WEB it was one of the first radio stations to have been established and licensed in the Greater St. Louis metropolitan area, and was known for most of its life as WIL. The Federal Communications Commission revoked the license for the station and its three co-owned stations in March 2020 after discovering that a convicted felon had effective control of the stations in their last years; despite the revocation, KZQZ and KQQZ continued to broadcast without a valid license into April 2020.[1]

The former KZQZ's four-tower transmitter site is in the village of Dupo, Illinois.[citation needed]

History

Experimental broadcasts by The Benwood Company

KZQZ traces its founding to April 5, 1922, the date that radio station WEB was first licensed to The Benwood Company of St. Louis.[2] This makes it one of four St. Louis radio stations awarded a license in the spring of 1922.

In the year-and-a-half prior to WEB's first license, the Benwood Company and its owners had made several experimental broadcasts on an irregular schedule. The Benwood Company was a small electrical firm, specializing in radio, that was named after its co-founders, the company's president William E. Woods, and vice president Lester Arthur "Eddie" Benson. On election night November 2, 1920, the two men broadcast election results provided by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper, over a radiotelephone transmitter operated at Woods' home at 4312 De Tonty Street.[3] (At least three other stations made election night broadcasts: the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company at East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania under a Special Amateur authorization, 8ZZ (now KDKA), the Detroit News' "Detroit News Radiophone" station, operating under an amateur station authorization, 8MK (now WWJ),[4] and the Buffalo Evening News, over an amateur station operated by Charles C. Klinck, Jr.[5])

Benson and Woods continued to work on developing radiotelephone equipment, and an early December 1920 newspaper article stated that they had successfully communicated with an automobile over a distance of 30 miles (48 kilometers). At the time, it was noted that "The wireless telephone will be the last word in luxury tourists", and it also could be installed on police department automobiles for emergency communication.[6] The two also made a few additional experimental radio broadcasts, from a variety of sites and apparently under multiple station licenses, although details are limited.[7] On January 29, 1922, it was announced that Woods was preparing a radio concert for the upcoming Friday evening featuring the City Club Quartet, to be followed at noon on Saturday by an address by Beatrice Forbes Robertson on the "Causes and Cure of Labor Unrest".[8]

The St. Louis Star began working in conjunction with The Benwood Company, a partnership that would expand over the next few years. The newspaper arranged for Benson and Woods to conduct a broadcast on February 9, 1922, from the Benwood building located at 1110 Olive Street, and following its successful completion the effort was hailed by the paper as "the first elaborate program given by wireless in this section of the United States".[9] A second Star-promoted broadcast was made two weeks later, on February 23.[10] It was announced that a third concert would be held on March 16, 1922, transmitting on the standard amateur radio station wavelength of 200 meters (1500 kHz) from Benson's home at 4942 Wiesehan Avenue.[11] However, this broadcast was canceled shortly before it was scheduled to take place, when L. R. Schmidt, in charge of monitoring the federal government's ninth Radio Inspection district, notified the participants that he had begun strictly enforcing a rule, adopted effective December 1, 1921, that banned amateur radio stations from making broadcasts intended for the general public.[12]

WEB

The December 1, 1921, regulations mandated that stations wishing to make broadcasts now had to hold a Limited Commercial license that explicitly authorized the broadcasts. The Benwood Company filed the necessary paperwork, and on April 5, 1922, was issued a broadcasting station license with the randomly assigned call letters of WEB.[2] The authorization included permission to use both wavelengths that had been set aside by the government for broadcasting stations: 360 meters (833 kHz) for "entertainment" and 485 meters (619 kHz) for "market and weather news".[13]

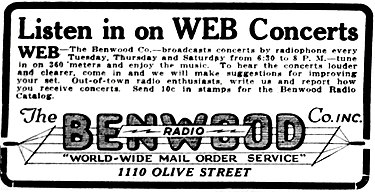

WEB was the fourth St. Louis radio station to receive a broadcasting license, preceded by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch's KSD (March 14, 1922, now KTRS), St. Louis University's WEW (March 23, 1922), and the Stix-Baer-Fuller department store's WCK (April 3, 1922, deleted November 30, 1928, as WSBF). At this time all broadcasters transmitted their entertainment programs on 360 meters, so the stations in a given area had to establish a time-sharing agreement specifying the time periods during which each would operate. A Benwood Company advertisement that appeared in early May listed WEB's schedule as 6:30 to 8:00 p.m. on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday evenings.[14] In late April it was announced that WEB had installed a 300-watt transmitter — a high power for the time — consisting of six 50-watt tubes.[15]

WIL

In November 1924, ownership of WEB was transferred to the Benson Radio Company, and in January 1925 the station's call sign was changed to WIL.[17] Shortly thereafter primary responsibility for the station's operations was taken over by the Star. A new studio was built on the eighth floor of the Star building, and the station licensee was changed to "St. Louis Star and the Benson Co." After a short series of tests, the newspaper announced that regular programming from the new studio would start on January 31, and the station's schedule would be 10 p.m. to midnight on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday, and 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. on Friday. WIL was now broadcasting on 1100 kHz, a frequency it shared with WCK.[18] This arrangement lasted until early 1927, when the Benson Radio Broadcasting Company resumed as the sole operator, and the station's studios were moved to the Missouri Hotel Building.[19]

There were numerous frequency shifts during the WIL's early history, until, in mid-1929, the station was assigned to part-time operation on a low-powered "local" frequency, 1200 kHz. It initially shared this frequency with two other St. Louis stations, WMAY and KFWF, but after both of these stations were deleted in the early 1930s WIL was able to operate fulltime.[20]

A station advertisement in a 1933 issue of Broadcasting magazine claimed a number of "firsts" for WIL, including:

- first commercial station on the air in St. Louis

- first to broadcast police news

- first to broadcast election returns and

- first to have its own news-gathering organization.[16]

In the 1930s, WIL branded itself as "The Biggest Little Station in the Nation".[21] Under the provisions of the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement, in March 1941 it, along with all the other stations transmitting on 1200 kHz, was moved to 1230 kHz. In 1949, WIL received permission to shift to a "regional" frequency, 1430 kHz, where it and its successors have been ever since. This new frequency also resulted in a major power increase, from 250 to 5,000 watts.[20]

WIL replaced KXOK (now KYFI) as St. Louis's ABC Radio affiliate on April 28, 1957.[22] Later that year, the Bensons sold WIL, along with Fort Lauderdale, Florida sister station WWIL, to H. &. E. Balaban Corp. for $650,000.[23] Beginning in the 1950s WIL was the first station in St. Louis to air a popular music format, and it was an early career stop in the late 1950s and early 1960s for some personalities who later achieved success in New York City radio, including WABC's Dan Ingram and Ron Lundy. It also boasted Jack Carney.[24] WIL's rating eventually shrank due to competition from Storz Broadcasting's KXOK.

In 1967, the Balabans sold WIL and its FM sister station, WIL-FM at 92.3 MHz, to LIN Broadcasting for $1.65 million;[25] LIN immediately announced plans to program WIL as an all-news station.[26] After one year, LIN changed WIL's format to country music on July 8, 1968.[27] It became St. Louis's top country music outlet, while featuring personalities such as Davey Lee.

In the mid-1970s, facing competition from startup country station WGNU-FM in Granite City, Illinois at 106.5 (now WARH), WIL's programs began to be simulcast over WIL-FM. By the early 1980s, WIL-FM was established as the top country music station in town, so the programming at the two stations was again separated, with WIL, on the AM band, adopting a classic country format.

LIN Broadcasting put its radio stations up for sale on September 23, 1986;[28] that November, it agreed to sell WIL and WIL-FM, along with its stations in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Rochester, New York, to Heritage Communications in a $23 million deal.[29] The following year, as part of Heritage's merger with Tele-Communications Inc., its stations were spun off to the company's executives for $200 million,[30] forming Heritage Media.[31]

WRTH

On June 21, 1990, WIL switched to an adult standards format, using Unistar's "Hits of the '40s, '50s and '60s" programming.[32] That December, it announced a call sign change to WRTH,[33] which took effect on January 18, 1991.[34] The station inherited the format and call sign used for many years at 590 AM in Wood River, Illinois (now KFNS AM).

Sinclair Broadcast Group announced that it would acquire the Heritage Media stations for $630 million on July 14, 1997;[35] the sale was completed in early 1998.[36] Heritage was in the process of being acquired by News Corporation, which had no interest in operating radio stations.[37] Emmis Communications announced plans to acquire Sinclair's St. Louis stations in June 1999;[38] a year later, following subsequent litigation, Emmis agreed to only acquire six radio stations for $220 million, with Sinclair retaining television station KDNL-TV.[39] Emmis then turned around and swapped WRTH, WIL-FM, and WVRV (now WXOS), along with its own WKKX (now WARH), to Bonneville International in exchange for KZLA-FM in Los Angeles; both deals were completed in October 2000.[40]

Facing the aging demographics of the nostalgia format, WRTH to a short-lived 50s/60s oldies format, dubbed "Real Oldies 1430", on June 27, 2003.[41] The adult standards format returned October 12, 2004.[42]

Return to WIL

The call sign was changed back to WIL on June 29, 2005;[34] on July 1, the station relaunched as "Country Legends 1430" with a classic country format.[43]

On July 20, 2006, severe thunderstorms caused major damage around St. Louis, leaving hundreds of thousands without electricity, and knocking down one of WIL's transmitting towers. (At the same time, two of the KTRS AM 550 towers were toppled, and KSLG AM 1380 was knocked off the air as well.) WIL had to apply for a special temporary authority from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to operate non-directionally with reduced power until the tower was replaced.[44]

In fall 2006, the station began serving as the St. Louis affiliate of the Missouri State University Basketball Network, airing broadcasts of the men's basketball games, which originated from KTXR radio in Springfield, Missouri.[citation needed]

KZQZ

In January 2008, Bonneville agreed to sell the station to the Entertainment Media Trust for $1.2 million; the deal did not include the rights to the WIL call sign.[45] Following the sale's completion,[46] on March 5, 2008, the call sign was changed to KZQZ,[34] and the format was changed to oldies, branded as "Krazy Q".[47]

KZQZ and its sister Entertainment Media Trust stations had their licenses revoked on March 20, 2020, for being controlled by Bob Romanik, a convicted felon. Despite the license revocation, KZQZ programming continued on 1430 kHz, effectively as pirate radio, until early April 2020, just after the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published stories about the continuing illegal broadcasts.[1]

FCC Auction 109

The FCC announced on February 8, 2021, that the former EMT-licensed AM allocations in the St. Louis market, including KZQZ's frequency, would go up for auction on July 27, 2021.[48] No bids were received for any of the four frequencies during the eight-day auction.[49]

References

- ^ a b Holleman, Joe (April 8, 2020). "Main shock-jock station still on air without FCC license". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, May 1, 1922, page 5. Limited Commercial license, serial #604.

- ^ "Wireless Phone Relays Returns of Post-Dispatch", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 3, 1920, page 3.

- ^ "Screen, Radio Give Returns", Detroit News, November 3, 1920, pages 1-2.

- ^ "'News' Wireless Service on Election Wins Praise", Buffalo Evening News, November 4, 1920, page 2.

- ^ "Wireless Telephone for Autos Perfected", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 3, 1920, page 16.

- ^ In the June 30, 1920 issue of Amateur Radio Stations of the United States, Benson is listed as holding a standard amateur license with the call sign 9KV, with Woods licensed as 9LC. In late 1920, Benson was upgraded to a Special Amateur license, with the call sign 9ZB. The June 30, 1921 issue of Amateur Radio Stations of the United States still has Woods as 9LC, with The Benwood Company now having its own standard amateur license, 9LA. These same two assignments also appear in the June 30, 1922 edition.

- ^ "Three Club Speakers on City Club Program this Week", St. Louis Star, January 29, 1922, page 8.

- ^ "Radio Association in St. Louis is Live Wire Organization", St. Louis Star, February 11, 1922, page 3.

- ^ "The Star's Next Radio Concert on Thursday", St. Louis Star, February 21, 1922, page 3.

- ^ "Wesley Barry on the Star's Radio Program Tonight", St. Louis Star, March 16, 1922, page 3.

- ^ "St. Louis Radio Amateurs Take Examination for U. S. License", St. Louis Star, March 17, 1922, page 15.

- ^ "Date First Licensed", Federal Communications Commission "History Cards" for WIL.

- ^ Benwood Company advertisement, St. Louis Star, May 4, 1922, page 10.

- ^ "1,000-Mile Set Installed by St. Louis Concern", St. Louis Star, April 23, 1922, page 2.

- ^ a b WIL Advertisement Broadcasting, April 15, 1933, page 5.

- ^ "Alterations and Corrections", Radio Service Bulletin, February 2, 1925, page 9.

- ^ "Tune in on The Star, WIL, Saturday Night", St. Louis Star, January 29, 1925, page 1.

- ^ "First Radio Broadcast Here 8 Years Ago to be Repeated on Anniversary", St. Louis Star, February 3, 1930, page 8.

- ^ a b History of WIL (route56.com)

- ^ WIL Advertisement, Broadcasting, May 15, 1935, page 37.

- ^ "WIL Affiliates With ABC Radio" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. April 29, 1957. p. 105. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Balaban $650,000 Buy Among Six Sales Announced" (PDF). Broadcasting-Telecasting. May 20, 1957. p. 10. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Dan Ingram, jock from WIL's Top 40 days, dies at 83". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. June 25, 2018.

- ^ "St. Louis, San Antonio, Raleigh stations sold" (PDF). Broadcasting. April 17, 1967. p. 10. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "LIN Buys WIL; AM All-News". Billboard. April 29, 1967. p. 26. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "WIL Drops All-News Idea For Country; Adds New DJs". Billboard. July 13, 1968. p. 13. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ Storch, Charles (September 24, 1986). "LIN Broadcasting Puts Radio Stations On Block". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Changing Hands" (PDF). Broadcasting. November 10, 1986. p. 92. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Heritage Stockholders Approve Buyout By Tele-Communications Inc". Associated Press. June 30, 1987. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Heritage's Hoak and his vision of success" (PDF). Broadcasting. November 14, 1988. pp. 64–5. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Timing Is Everything" (PDF). Radio & Records. June 29, 1990. p. 29. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Cocktail Chatter" (PDF). Radio & Records. December 14, 1990. p. 33. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Call Sign History (DKZQZ)". CDBS Public Access. Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Sinclair to buy Heritage radio and TV stations". The New York Times. Reuters. July 17, 1997. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ "Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. Form 10-K" (TXT). EDGAR. Securities and Exchange Commission. March 30, 1998. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ Fabrikant, Geraldine (March 18, 1997). "News Corporation Buying Heritage Media of Dallas". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- ^ "Emmis to buy Sinclair stations here". St. Louis Business Journal. June 25, 1999. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Sinclair to sell six radio stations to Emmis". St. Louis Business Journal. June 22, 2000. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Emmis completes purchase of Sinclair's St. Louis stations". St. Louis Business Journal. October 6, 2000. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "'Real Oldies' Arrives in St. Louis", Radio & Records, July 4, 2003, page 3.

- ^ "WRTH AM to return to original format Wednesday". St. Louis Business Journal. October 11, 2004. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "WRTH-AM/St. Louis Now Classic Country" (PDF). Radio & Records. July 8, 2005. p. 3. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ (beradio.com)

- ^ "Bonneville Sells St. Louis AM". All Access. January 3, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Bonneville spins station, keeps calls". Radio & Television Business Report. March 6, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ Lussenhop, Jessica (August 2, 2012). "Romanik's Interlude: An ex-con finds his second calling as the "Grim Reaper of Radio"". Riverfront Times. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ McLane, Paul (February 8, 2021). "FCC Schedules Auction of 136 FM CPs". RadioWorld. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "iHeartMedia Nabs Sacramento FM In FCC Auction; Four St. Louis AMs Are Left Unsold". Inside Radio. August 6, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

External links

- FCC History Cards for KZQZ (covering 1927–1981 as WIL)