LIMSwiki

Contents

| Battle of al-Funaydiq | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fatimid–Mirdasid wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Fatimid Caliphate Banu Kalb Banu Tayy |

Banu Kilab (Mirdasids) ahdath of Aleppo | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Nasir al-Dawla Ibn Hamdan (POW) | Mahmud ibn Nasr | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 15,000 cavalry | c. 2,000 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Very heavy | Unknown | ||||||

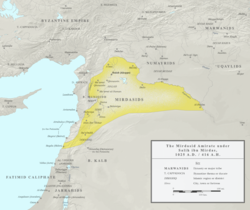

Location in modern Syria | |||||||

The Battle of al-Funaydiq took place on 30 August 1060, between the forces of the Fatimid Caliphate under Nasir al-Dawla Ibn Hamdan, and the forces of the renegade Mirdasid chieftain of the Banu Kilab, Mahmud ibn Nasr, who aimed to capture Aleppo. The battle was a comprehensive defeat for the Fatimids after their Bedouin allies switched sides, resulting in the capture of Ibn Hamdan and most of his commanders. As a result of the battle, Aleppo surrendered to Mahmud ibn Nasr, ending direct Fatimid rule over the city for good.

Background

The Emirate of Aleppo in northern Syria had been a target of the Fatimid Caliphate since its first expansion in the region under Caliph al-Aziz (r. 975–996). After a series of confrontations with its Hamdanid rulers and the Byzantine Empire, which also claimed the city as its vassal, a permanent peace was reached in 1001 with a mutually acceptable modus vivendi that left Aleppo as a buffer state beholden to both Fatimids and Byzantines.[1] This did not prevent both sides from trying to install their own candidates in Aleppo in the following years, the situation further complicated by the rulers of Aleppo trying to play both powers against each other, and the rising influence of the Bedouin tribe of the Banu Kilab, led by the Mirdasids, who pursued their own interests. Thus a period of direct Fatimid rule in 1017–1024 was followed by Mirdasid rule over the city, interrupted only in 1038–1042, when it was in the hands of the Fatimid comamnder-in-chief in Syria, Anushtakin al-Dizbari.[2][3] After defeating Fatimid attacks against him in 1048 an 1050, Emir Mu'izz al-Dawla Thimal (r. 1042–1057, 1061–1062) managed to receive recognition from both Cairo and Constantinople, paying tribute to both.[4][5]

As his rule became increasingly contested by his fellow Kilabi tribesmen,[6] in January 1057 Thimal agreed to hand over Aleppo to a Fatimid governor, Ibn Mulhim, in exchange for the port cities of Byblos, Beirut, and Acre.[7] The defeat of the Fatimid-sponsored attempt by al-Basasiri to capture Baghdad and end the Abbasid Caliphate in January 1060,[8] had repercussions in Syria, where Fatimid prestige fell; the city of Rahba, which had been handed over by Thimal to serve as the expedition's base of operations, was captured by Thimal's brother Atiyya, with all the treasure and stores of arms kept there.[6] At the same time, the Kilab decided to support Mahmud, a nephew of Thimal and son of the former emir Shibl al-Dawla Nasr (r. 1029–1038), as their candidate for recovering control of Aleppo itself. Along with his cousin, Mani ibn Muqallad, Mahmud launched an attack on the city in June 1060, but after seven days of fruitless combat, he was forced to retreat.[9] However, Ibn Mulhim found himself confronted with the demands of the urban militia (ahdath) for additional payments. When the Fatimid governor refused, the ahdath rose in revolt in July and opened the gates of the city to Mahmud, while Ibn Mulhim sought refuge in the Citadel of Aleppo.[10]

Battle

Ibn Mulhim immediately sent to Cairo for help. The governor of Damascus, Nasir al-Dawla Abu Ali al-Husayn—son of the Fatimid commander who had led the failed attack in 1048[11]—was tasked with suppressing the revolt. He moved to Homs, Baalbek, and then Apamea. The Kilab and Banu Khafaja Bedouin first moved to meet him, but through the intercession of Atiyya, they dispersed and retreated north to Qinnasrin.[12] From Apamea, Nasir al-Dawla called upon the Kilab, who in theory were still Fatimid allies, to join him. He is said to have extracted forty consecutive oaths from those that appeared before him, to ensure their loyalty, before he moved on Aleppo, but at Sarmin the Kilab abandoned the Fatimid army and moved east, where the rest of the tribe were gathering.[13]

In the meantime, in Aleppo, on 7 August most of the ahdath left the city to join the gathering Kilab. Ibn Mulhim retook possession of the lower city, which his Berber soldiers plundered. Some forty of the ahdath who had not left and were taken prisoner were executed; their bodies were publicly exposed at the crossroads of the city.[13] So thorough was the despoliation by Ibn Mulhim's men, who knew the city well and thus were aware of where to look, that when Nasir al-Dawla arrived a few days later and wanted to loot the city himself, he was told that it was useless. He tried to oblige the Aleppines to pay him a bounty of 50,000 gold dinars for driving Mahmud away, but nothing came of it before the Fatimid army left to confront Mahmud's forces.[13]

According to the 13th-century Aleppine historian Ibn al-Adim, Nasir al-Dawla had 15,000 horse with him, including not only Fatimid regular troops but also Bedouin allies from the Banu Kalb and Banu Tayy tribes, while Mahmud disposed of 2,000 men. The two armies met at a place called al-Funaydiq on Tell Sultan, on 30 August 1060. The battle turned into a rout for the Fatimid army: tormented by thirst, it was deserted by its Bedouin allies. Nasir al-Dawla and many of his commanders were taken prisoner along with most of their men who were not killed outright. A few soldiers managed to escape, after shedding their clothing.[14]

Aftermath

Already on the next day, Atiyya, who had not taken part in the battle, appeared at Aleppo and received the surrender of the lower city by Ibn Mulhim, who once again withdrew to the citadel. However, on the same evening, Mahmud appeared before the city with his men. Atiyya fled and Ibn Mulhim, bereft of any prospect of relief, capitulated on 9 September. Mahmud's son, and three more sons of Kilabi chieftains, were sent as hostages to Apamea, after which Ibn Mulhim exited the citadel. The Kilab escorted him safely to Apamea, before returning to Aleppo with the hostages.[15] The loss of Aleppo also voided the agreement between the Fatimids and Thimal, as Caliph al-Mustansir (r. 1036–1094) informed the latter. This led to another internecine conflict among the Mirdasids, as Thimal sought to return to Aleppo and Mahmud refused to give up the city to his uncle.[16] To gain the support of the Fatimids, he released Nasir al-Dawla and the other commanders captured at al-Funaydiq.[17] In the event, the conflict was ended by a mediation of the Kilabi tribal elders: Thimal returned to Aleppo, while Mahmud was compensated with money. Atiyya, in the meantime, still in control of Rahba, proclaimed himself independent.[18] The death of Thimal in 1062 reopened the succession struggle, which was ended only in 1065, with a de facto division of the Emirate of Aleppo between Mahmud and Atiyya.[18]

The defeat at the battle of al-Funaydiq marked the definitive end of Fatimid ambitions for direct rule over Aleppo and northern Syria.[18] However the city, which was still mostly populated by Shi'ites,[19] retained the allegiance to the Fatimid caliphs, in whose name the sermon of the Friday prayer continued to be said.[15] This lasted until 1070, when pressure from the Seljuk Empire led to the recognition of the Sunni Abbasid caliph instead.[20]

See also

References

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 153, 155–157, 161–164, 269–270.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 270–273, 332–350, 359–362.

- ^ Bianquis 1993, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 359–362.

- ^ Bianquis 1993, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Bianquis 1993, p. 119.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, p. 565.

- ^ Halm 2003, pp. 383–395.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, pp. 568–569.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, p. 569.

- ^ Bianquis 1993, pp. 118, 120.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, pp. 569–570.

- ^ a b c Bianquis 1989, p. 570.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, pp. 570–571.

- ^ a b Bianquis 1989, p. 571.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, pp. 571–573.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, p. 573.

- ^ a b c Bianquis 1993, p. 120.

- ^ Halm 2003, p. 418.

- ^ Bianquis 1989, pp. 590–592.

Sources

- Bianquis, Thierry (1989). Damas et la Syrie sous la domination fatimide (359-468/969-1076). Deuxième tome (in French). Presses de l’Ifpo. doi:10.4000/books.ifpo.6458. ISBN 978-2-35159-526-8.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1993). "Mirdās, Banū or Mirdāsids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 115–123. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_5220. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Halm, Heinz (2003). Die Kalifen von Kairo: Die Fatimiden in Ägypten, 973–1074 [The Caliphs of Cairo: The Fatimids in Egypt, 973–1074] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-48654-1.