LIMSwiki

Contents

| Battle of Mons | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Frontiers of the First World War | |||||||||

British soldiers from the Royal Fusiliers resting in the town square at Mons before entering the line prior to the Battle of Mons. The Royal Fusiliers faced some of the heaviest fighting in the battle and earned the first Victoria Cross of the war. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,638 | 2,000–5,000 | ||||||||

Mons: Belgian town and capital of Hainaut | |||||||||

The Battle of Mons was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the First World War. It was a subsidiary action of the Battle of the Frontiers, in which the Allies clashed with Germany on the French borders. At Mons, the British Army attempted to hold the line of the Mons–Condé Canal against the advancing German 1st Army. Although the British fought well and inflicted disproportionate casualties on the numerically superior Germans, they were eventually forced to retreat due both to the greater strength of the Germans and the sudden retreat of the French Fifth Army, which exposed the British right flank. Though initially planned as a simple tactical withdrawal and executed in good order, the British retreat from Mons lasted for two weeks and took the BEF to the outskirts of Paris before it counter-attacked in concert with the French, at the Battle of the Marne.

Background

Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914 and on 9 August, the BEF began embarking for France.[1] Unlike Continental European armies, the BEF in 1914 was exceedingly small. At the beginning of the war, the German and French armies numbered well over a million men each, divided into eight and five field armies respectively; the BEF had c. 80,000 soldiers in two corps of entirely professional soldiers made up of long-service volunteer soldiers and reservists. The BEF was probably the best trained and most experienced of the European armies of 1914.[2] British training emphasised rapid-fire marksmanship and the average British soldier was able to hit a man-sized target fifteen times a minute, at a range of 300 yards (270 m) with his Lee–Enfield rifle.[3] This ability to generate a high volume of accurate rifle-fire played an important role in the BEF's battles of 1914.[4]

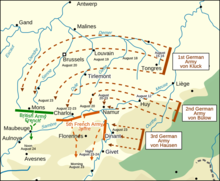

The Battle of Mons took place as part of the Battle of the Frontiers, in which the advancing German armies clashed with the advancing Allied armies along the Franco-Belgian and Franco-German borders. The BEF was stationed on the left of the Allied line, which stretched from Alsace-Lorraine in the east to Mons and Charleroi in southern Belgium.[5][6] The British position on the French flank meant that it stood in the path of the German 1st Army, the outermost wing of the massive "right hook" intended by the Schlieffen Plan (a combination of the Aufmarsch I West and Aufmarsch II West deployment plans), to pursue the Allied armies after defeating them on the frontier and force them to abandon northern France and Belgium or risk destruction.[7]

The British reached Mons on 22 August.[8] In the afternoon of that same day arrived a message from the French Fifth Army commander, General Charles Lanrezac, sent to Field Marshal Sir John French requesting the BEF to turn right to attack von Bülow's advancing flank. The French Fifth Army, located on the right of the BEF, was engaged with the German 2nd and 3rd armies at the Battle of Charleroi. French refused, instead agreeing to hold the line of the Condé–Mons–Charleroi Canal for twenty-four hours, to prevent the German 1st Army from threatening the French left flank. The British spent the day digging in along the canal.[9] [10]

Prelude

British preparations

At the Battle of Mons the BEF had some 80,000 men, comprising the Cavalry Division, an independent cavalry brigade and two corps, each with two infantry divisions.[11] I Corps was commanded by Sir Douglas Haig and was composed of the 1st and 2nd divisions. II Corps was commanded by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien and consisted of the 3rd and 5th divisions.[8] Each division had 18,073 men and 5,592 horses, in three brigades of four battalions. Each division had twenty-four Vickers machine guns – two per battalion – and three field artillery brigades with fifty-four 18-pounder guns, one field howitzer brigade of eighteen 4.5-inch howitzers and a heavy artillery battery of four 60-pounder guns.[12]

II Corps, on the left of the British line, occupied defensive positions along the Mons–Condé Canal, while I Corps was positioned almost at a right angle away from the canal, along the Mons–Beaumont road (see map).[13] I Corps was deployed in this manner to protect the right flank of the BEF in case the French were forced to retreat from their position at Charleroi.[8] I Corps did not line the canal, which meant that it was little involved in the battle and the German attack was faced mostly by II Corps.[14] The dominant geographical feature of the battlefield, was a loop in the canal, jutting outwards from Mons towards the village of Nimy. This loop formed a small salient which was difficult to defend and formed the focus of the battle.[15]

The first contact between the two armies occurred on 21 August, when a British bicycle reconnaissance unit encountered a German force near Obourg and Private John Parr became the first British soldier to be killed in the war.[16] The first substantial action occurred on the morning of 22 August. At 6:30 a.m., the 4th Royal Irish Dragoons laid an ambush for a patrol of German lancers outside the village of Casteau, to the north-east of Mons.[17] When the Germans spotted the trap and fell back, a troop of the dragoons, led by Captain Charles Hornby gave chase, followed by the rest of his squadron, all with drawn sabres. The retreating Germans led the British to a larger force of lancers, whom they promptly charged and Hornby became the first British soldier to kill an opposing soldier in the Great War, fighting on horseback with sword against lance. After a further pursuit of a few miles, the Germans turned and fired upon the Irish cavalry, at which point the dragoons dismounted and returned fire. Private E. Edward Thomas, a cavalryman and drummer, is reputed to have fired the first shot of the war for the British Army, hitting a German trooper.[18][a]

That same day, having used British reconnaissance planes along with Lanrezac's messaging to his army staff, the BEF's chief of intelligence, Colonel George Macdonogh, warned Sir John French that three German army corps were advancing straight against them. The field marshal chose to ignore these claims, instead proposing to advance towards Soignies.[20]

German preparations

Advancing towards the British was the German 1st Army, commanded by Alexander von Kluck.[6] The 1st Army was composed of four active corps (II, III, IV, and IX corps) and three reserve corps (III, IV and IX reserve corps), although only the active corps took part in the fighting at Mons. German corps had two divisions each, with attendant cavalry and artillery.[21] The 1st Army had the greatest offensive power of the German armies, with a density of c. 18,000 men per 1 mi (1.6 km) of front, or about ten per 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[22]

Late on 20 August, General Karl von Bülow, the 2nd Army commander, who had tactical control over the 1st Army while north of the Sambre, held the view that an encounter with the British was unlikely and wished to concentrate on the French units reported between Charleroi and Namur, on the south bank of the Sambre; reconnaissance in the afternoon failed to reveal the strength or intentions of the French. The 2nd Army was ordered to reach a line from Binche, Fontaine-l'Eveque and the Sambre next day to assist the 3rd Army across the Meuse by advancing south of the Sambre on 23 August. The 1st Army was instructed to be ready to cover Brussels and Antwerp to the north and Maubeuge to the south-west. Kluck and the 1st Army staff expected to meet British troops, probably through Lille, which made a wheel to the south premature. Kluck wanted to advance to the south-west to maintain freedom of manuoeuvre and on 21 August, attempted to persuade Bülow to allow the 1st Army to continue its manoeuvre. Bülow refused and ordered the 1st Army to isolate Maubeuge and support the right flank of the 2nd Army, by advancing to a line from Lessines to Soignies, while the III and IV reserve corps remained in the north, to protect the rear of the army from Belgian operations southwards from Antwerp.[23]

On 22 August, the 13th Division of the VII Corps, on the right flank of the 2nd Army, encountered British cavalry north of Binche, as the rest of the army to the east began an attack over the Sambre river, against the French Fifth Army. By the evening the bulk of the 1st Army had reached a line from Silly to Thoricourt, Louvignies and Mignault; the III and IV reserve corps had occupied Brussels and screened Antwerp. Reconnaissance by cavalry and aircraft indicated that the area to the west of the army was free of troops and that British troops were not concentrating around Kortrijk (Courtrai), Lille and Tournai but were thought to be on the left flank of the Fifth Army, from Mons to Maubeuge. Earlier in the day, British cavalry had been reported at Casteau, to the north-east of Mons. A British aeroplane had been seen at Louvain (Leuven) on 20 August and on the afternoon of 22 August, a British aircraft en route from Maubeuge, was shot down by the 5th Division. More reports had reached the IX Corps, that columns were moving from Valenciennes to Mons, which made clear the British deployment but were not passed on to the 1st Army headquarters. Kluck assumed that the subordination of the 1st Army to the 2nd Army had ended, since the passage of the Sambre had been forced. Kluck wished to be certain to envelop the left (west) flank of the opposing forces to the south but was again over-ruled and ordered to advance south, rather than south-west, on 23 August. [24]

Late on 22 August, reports arrived that the British had occupied the Canal du Centre crossings from Nimy to Ville-sur-Haine, which revealed the location of British positions, except for their left flank. On 23 August, the 1st Army began to advance north-west of Maubeuge, to a line from Basècles to St. Ghislain and Jemappes. The weather had turned cloudy and rainy, which grounded the 1st Army Flieger-Abteilung all day, despite an improvement in the weather around noon. News that large numbers of troops had been arriving at Tournai by train were received and the advance was suspended, until the reports from Tournai could be checked. The IX Corps divisions advanced in four columns against the Canal du Centre, from the north of Mons to Roeulx and on the left (eastern) flank, met French troops at the canal, which was thought to be the junction of the British and French forces. The corps commander, General von Quast, had ordered an attack for 9:55 a.m. to seize the crossings, before the halt order was received. The two III Corps divisions were close to St. Ghislain and General Ewald von Lochow ordered them to prepare an attack from Tertre to Ghlin. In the IV Corps area, General Friedrich Sixt von Armin ordered an attack on the canal crossings of Péruwelz and Blaton and ordered the 8th Division to reconnoitre from Tournai to Condé and to keep contact with Höhere Kavallerie-Kommando 2 (HKK 2, II Cavalry Corps).[25]

Battle

Morning

At dawn on 23 August, a German artillery bombardment began on the British lines; throughout the day the Germans concentrated on the British at the salient formed by the loop in the canal.[26] At 9:00 a.m., the first German infantry assault began, with the Germans attempting to force their way across four bridges that crossed the canal at the salient.[27] Four German battalions attacked the Nimy bridge, which was defended by a company of the 4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers and a machine-gun section led by Lieutenant Maurice Dease. Advancing at first in close column, "parade ground formation", the Germans made easy targets for the riflemen, who hit German soldiers at over 1,000 yards (910 m), mowing them down by rifle, machine-gun and artillery fire.[28][29] So heavy was the British rifle fire throughout the battle that some Germans thought they were facing batteries of machine-guns.[30]

The German attack was a costly failure and the Germans switched to an open formation and attacked again. This attack was more successful, as the looser formation made it harder for the Irish to inflict casualties rapidly. The outnumbered defenders were soon hard-pressed to defend the canal crossings and the Royal Irish Fusiliers at the Nimy and Ghlin bridges only held on with piecemeal reinforcement and the exceptional bravery of two of the battalion machine-gunners.[32] At the Nimy bridge, Dease took control of his machine gun after the rest of the section had been killed or wounded and fired the weapon, despite being shot several times. After a fifth wound he was evacuated to the battalion aid station, where he died.[33] Private Sidney Godley took over and covered the fusilier retreat at the end of the battle but when it was his time to retreat he disabled the gun by throwing parts into the canal then surrendered.[34] Dease and Godley were awarded the Victoria Cross, the first awards of the First World War.[35] An equally brave attempt was made by Captain Theodore Wright of the Royal Engineers, who attempted to blow up five of the bridges that crossed the canal in a three mile run. He managed to destroy the Jemappes pass but while setting up charges at Mariette he was struck in the head by a projectile fragment and had to retreat. Having retreated for a small while, he nonetheless tried again protected by the cover fire of the Northumberland Fusiliers. However, he slipped and fell in the canal, being saved by a comrade and forced to give up the whole endeavour. For this action he was also awarded a Victoria Cross. Wright would be killed in action the following month at Vailly.[36]

To the right of the Royal Fusiliers, the 4th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, and the 1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, were equally hard-pressed by the German assault on the salient. Greatly outnumbered, both battalions suffered many casualties but with reinforcements from the Royal Irish Regiment, from the divisional reserve and support from the divisional artillery, they managed to hold the bridges.[37] The Germans expanded their attack, assaulting the British defences along the straight reach of the canal to the west of the salient. The Germans used the cover of fir plantations that lined the northern side of the canal and advanced to within a few hundred yards of the canal, to rake the British with machine-gun and rifle fire. The German attack fell particularly heavily on the 1st Battalion, Royal West Kent Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers, which despite many casualties, repulsed the Germans throughout the day.[38]

Retreat

By the afternoon, the British position in the salient had become untenable; the 4th Middlesex had suffered casualties of 15 officers and 353 other ranks killed or wounded.[39] To the east of the British position, units of the German IX Corps had begun to cross the canal in force, threatening the British right flank. At Nimy, Private Oskar Niemeyer had swum across the canal under British fire to operate machinery closing a swing bridge. Although he was killed, his actions re-opened the bridge and allowed the Germans to increase pressure against the 4th Royal Fusiliers.[40][41]

Having returned from Valenciennes, Commander-in-Chief Sir John French was still convinced that an advance could soon be made, however, by 3:00 p.m., the 3rd Division was ordered to retire from the salient, to positions a short distance to the south of Mons and a similar retreat towards evening by the 5th Division to conform. By nightfall, II Corps had established a new defensive line running through the villages of Montrœul, Boussu, Wasmes, Paturages and Frameries. The Germans had built pontoon bridges over the canal and were approaching the British positions in great strength. News had arrived that the French Fifth Army was retreating, dangerously exposing the British right flank and at 2:00 a.m. on 24 August, II Corps was ordered to retreat south-west into France to reach defensible positions along the Valenciennes–Maubeuge road.[42] Sir John finally accepted that an advance would not be able to take place and admitted that a retreat had to be made quickly, else the consequences would be irreparable for the BEF.[43]

The unexpected order to retreat from prepared defensive lines in the face of the enemy, meant that II Corps was required to fight a number of sharp rearguard actions against the Germans. For the first stage of the withdrawal, Smith-Dorrien detailed the 15th Brigade of the 5th Division, which had not been involved in heavy fighting on 23 August, to act as rearguard. On 24 August they fought various holding actions at Paturages, Frameries and Audregnies. During the engagement at Audregnies the 1st Battalions of the Cheshire and Norfolk regiments halted the German advance from Quiévrain and Baisieux until the morning of 25 August despite being outnumbered and suffering ruinous losses, and with the support of the 5th Brigade artillery, they also inflicted many casualties on the advancing German regiments. An evening roll call of the Cheshires 1st Battalion, who had not received a withdrawal order, indicated that their establishment had been reduced by almost 80 per cent. Their refusal to fall back without orders led Smith-Dorrien to later state that on reflection the 1st Battalion, Cheshires together with the Duke of Wellington's regiment had "saved the BEF".[44]

At Wasmes, elements of the 5th Division faced a big attack; German artillery began bombarding the village at daybreak, and at 10:00 a.m. infantry of the German III Corps attacked. Advancing in columns, the Germans were immediately met with massed rifle and machine-gun fire and were "mown down like grass".[45] For a further two hours, soldiers of the Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st West Kents, 2nd Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, 2nd Battalion, Duke of Wellington's Regiment, and the 1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment, held off German attacks on the village, despite many casualties and then retreated in good order to St. Vaast.[46] On the extreme left of the British line, the 14th and 15th brigades of the 5th Division were threatened by a German outflanking move and were forced to call for help from the cavalry.[47] The 2nd Cavalry Brigade, along with the 119th Battery Royal Field Artillery (RFA) and L Battery RHA, were sent to their aid. Dismounting, the cavalry and the two artillery batteries screened the withdrawal of the 14th and 15th brigades in four hours of intense fighting.[48]

German 1st Army

On 23 August, the 18th Division of IX Corps advanced and began to bombard the British defences near Maisières and St. Denis. Part of the 35th Brigade, which contained large numbers of Danes from Northern Schleswig, got across the canal east of Nimy with few casualties and reached the railway beyond in the early afternoon but the attack on Nimy was repulsed. The 36th Brigade captured bridges at Obourg against determined resistance, after which the defenders of Nimy gradually withdrew; the bridges to the north were captured at 4:00 p.m. and the town stormed. Quast ordered the 18th Division to take Mons and push south to Cuesmes and Mesvin. Mons was captured unopposed, except for a skirmish on the southern fringe and by dark, the 35th Brigade was in the vicinity of Cuesmes and Hyon. On higher ground to the east of Mons, the defence continued. On the front of the 17th Division, British cavalry withdrew from the canal crossings at Ville-sur-Haine and Thieu and the division advanced to the St. Symphorien–St. Ghislain road. At 5:00 p.m., the divisional commander ordered an enveloping attack on the British east of Mons, who were pushed back after a stand on the Mons–Givry road.[49]

By 11:00 a.m., reports from the IV, III and IX corps revealed that the British were in St. Ghislain and at the canal crossings to the west, as far as the bridge at Pommeroeuil, with no troops east of Condé. Intelligence reports from 22 August, had noted 30,000 troops heading through Dour towards Mons and on 23 August, 40,000 men had been seen on the road to Genlis south of Mons, with more troops arriving at Jemappes. To the north of Binche, the right flank division of the 2nd Army had been forced back to the south-west by British cavalry. In the early afternoon, the II Cavalry Corps reported that it had occupied the area of Thielt–Kortryk–Tournai during the night and forced back a French brigade to the south-east of Roubaix. With this report indicating that the right flank was clear of Allied troops, Kluck ordered III Corps to advance through St. Ghislain and Jemappes on the right of IX Corps and for IV Corps to continue towards Hensis and Thulies; IV Corps was already attacking at the Canal du Centre, II Corps and IV Reserve Corps were following on behind the main part of the army.[50]

III Corps had to advance across meadows to an obstacle with few crossings, all of which had been destroyed. The 5th Division advanced towards Tertre on the right, which was captured but then the advance on the railway bridge was stopped by small-arms fire from across the canal. On the left flank, the division advanced towards a bridge north-east of Wasmuel and eventually managed to get across the canal against determined resistance, before turning towards St. Ghislain and Hornu. As dark fell, Wasmuel was occupied and attacks on St. Ghislain were repulsed by machine-gun fire, which prevented troops crossing the canal except at Tertre, where the advance was stopped for the night. The 6th Division was counter-attacked at Ghlin, before advancing towards higher ground south of Jemappes. The British in the village stopped the division with small-arms fire, except for small parties, who found cover west of a path from Ghlin to Jemappes. These isolated parties managed to surprise the defenders at the crossing north of the village, with the support of a few field guns around 5:00 p.m., after which the village was captured. The rest of the division crossed the canal and began a pursuit towards Frameries and Ciply but stopped as dark fell.[50]

IV Corps arrived in the afternoon, as the 8th Division closed on Hensies and Thulin and the 7th Division advanced towards Ville-Pommeroeuil, where there were two canals blocking the route. The 8th Division encountered the British at the northernmost canal, west of Pommeroeuil and forced back the defenders but then bogged down in front of the second canal, under machine-gun fire from the south bank. The attack was suspended after night fell and the British blew the bridge. The 7th Division forced the British back from a railway embankment and over the canal, to the east of Pommeroeuil but was pushed back from the crossing. Small parties managed to cross by a footbridge built in the dark and protected repair parties at the blown bridge, which allowed troops to get across and dig in 400 metres (440 yd) south of the canal, on either side of the road to Thulin.[51]

Late in the day, II Corps and IV Reserve Corps rested on their march routes at La Hamaide and Bierghes, after marching 32 and 20 kilometres (20 and 12 mi) respectively, 30 and 45 kilometres (19 and 28 mi) behind the front, too far behind to take part in the battle on 24 August. In the mid-afternoon of 23 August, IV Corps was ordered to rest, as reports from the front suggested that the British defence had been overcome and the 1st Army headquarters wanted to avoid the army converging on Maubeuge, leaving the right (western) flank vulnerable. In the evening, Kluck cancelled the instruction, after reports from IX Corps reporting that its observation aircraft had flown over a column 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long, moving towards Mons along the Malplaquet road. Two more columns were seen on the Malplaquet–Genly and the Quevy–Genly roads, a large force was seen near Asquillies and cavalry was found further east, which showed that most of the BEF was opposite the 1st Army. It was considered vital that the second canal crossings were captured along the line, as had been achieved by IX and part of III corps. IV Corps was ordered to resume its march and move the left wing towards Thulin but it was already engaged at the canal crossings. The III and IX corps' attack during the day, had succeeded against "a tough, nearly invisible enemy" but the offensive had to continue, because it appeared that only the right flank of the army could get behind the BEF.[52]

The situation remained unclear at the 1st Army headquarters in the evening, because communication with the other right flank armies had been lost and only fighting near Thuin by VII Corps, the right-flank unit of the 2nd Army had been reported. Kluck ordered that the attack was to continue on 24 August, past the west of Maubeuge and that II Corps would catch up behind the right flank of the army. IX Corps was to advance to the east of Bavay, III Corps was to advance to the west of the village, IV Corps was to advance towards Warnies-le-Grand 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) further to the west and II Cavalry Corps was to head towards Denain, to cut off the British retreat. During the night there were several British counter-attacks but none of the German divisions was forced back over the canal. At dawn IX Corps resumed its advance and pushed forwards against rearguards until the afternoon, when it stopped the advance due to uncertainty about the situation on its left flank and the proximity of Maubeuge. At 4:00 p.m. cavalry reports led Quast to resume the advance, which was slowed by the obstacles of Maubeuge and III Corps congesting the roads.[53]

On III Corps' front to the west, the 6th Division attacked Frameries at dawn, which held out until 10:30 a.m. and then took La Bouverie and Pâturages, after which the British began to retreat; the division turned west towards Warquignies and the 5th Division. St. Ghislain had been attacked by the 5th Division behind an artillery barrage, where the 10th Brigade had crossed the canal and taken the village in house-to-house fighting, then reached the south end of Hornu. A defensive line had been established by the British along the Dour–Wasmes railway, which stopped the German advance and diverted the 9th Brigade until 5:00 p.m., when the British withdrew. The German infantry were exhausted and stopped the pursuit at Dour and Warquignies. During the day Kluck sent liaison officers to the corps headquarters, stressing that the army should not converge on Maubeuge but pass to the west, ready to envelop the British left (west) flank.[54]

IV Corps' headquarters had ordered its divisions to attack over the canal at dawn but found that the British had blown the bridges and withdrawn. Repairs took until 9:00 a.m. and the 8th Division did not reach Quiévrain until noon; the 7th Division reached the railway at Thuin during the morning and then took Élouges late in the afternoon. As the 8th Division moved on, the vanguard was ambushed by British cavalry before an advance to Valenciennes could begin and then attacked a British rearguard at Baisieux, which then slipped away to Audregnies. The rest of the division skirmished with French Territorials south-west of Baisieux. The IV Corps' attack forced back rearguards but inflicted no serious damage, having been slowed by the bridge demolitions at the canals. The cavalry divisions had advanced towards Denain and the Jägerbattalions had defeated troops of the French 88th Territorial Division at Tournai and then reached Marchiennes, after a skirmish with the 83rd Territorial Division near Orchies.[54]

Air operations

German air reconnaissance detected British troops on 21 August, advancing from Le Cateau to Maubeuge, and on 22 August from Maubeuge to Mons, as other sources identified halting places, but poor communication and lack of systematic direction of air operations led to the assembly of the BEF from Condé to Binche being unknown to the Germans on 22–23 August.[55] British reconnaissance flights had begun on 19 August with two sorties and two more on 20 August, which reported no sign of German troops. Fog delayed flights on 21 August but in the afternoon German troops were seen near Kortrijk and three villages were reported to be burning. Twelve reconnaissance sorties were flown on 22 August and reported many German troops closing in on the BEF, especially troops on the Brussels–Ninove road, which indicated an enveloping manoeuvre. One British aircraft was shot down and a British observer became the first British soldier to be wounded while flying. By the evening Sir John French was able to discuss with his commanders the German dispositions near the BEF which had been provided by aircraft observation, the strength of the German forces, that the Sambre had been crossed and that an encircling move by the Germans from Geraardsbergen was possible. During the battle on 23 August, the aircrews flew behind the battlefield looking for troop movements and German artillery batteries.[56]

Aftermath

Analysis

By nightfall on 24 August, the British had retreated to what were expected to be their new defensive lines, on the Valenciennes–Maubeuge road. Outnumbered by the German 1st Army and with the French Fifth Army also falling back, the BEF had no choice but to continue to retire – I Corps retreating to Landrecies and II Corps to Le Cateau.[57] The chaos and confusion were graphically illustrated in Landrecies on 25 August, where a senior officer "apparently took leave of his senses and began firing his revolver down a street".[58] The Great Retreat continued for two weeks and covered over 250 miles (400 km). The British were closely pursued by the Germans and fought several rearguard actions, including the Battle of Le Cateau on 26 August, the Étreux rearguard action on 27 August and the action at Néry on 1 September.[59] Units disappeared and "More guns were lost than at any time since the American War of Independence."[60]

Both sides had success at the Battle of Mons: the British had been outnumbered by about 3:1 but managed to withstand the German 1st Army for 48 hours, inflict more casualties on the Germans and then retire in good order. The BEF achieved its main strategic objective, which was to prevent the French Fifth Army from being outflanked.[61] The battle was an important moral victory for the British; as their first battle on the continent since the Crimean War, it was a matter of great uncertainty as to how they would perform. In the event, the British soldiers came away from the battle with a clear sense that they had got the upper hand during the fighting at Mons. The Germans appeared to recognise that they had been dealt a sharp blow by an army they had considered inconsequential. German novelist and infantry officer Walter Bloem wrote:

The men all chilled to the bone, almost too exhausted to move and with the depressing consciousness of defeat weighing heavily upon them. A bad defeat, there can be no gainsaying it ... we had been badly beaten, and by the English – by the English we had so laughed at a few hours before.[62]

For the Germans, the Battle of Mons was a tactical repulse and a strategic success. The staff at Kluck's headquarters claimed that the two-day battle had failed to envelop the British, due to the subordination of the army to Bülow and the 2nd Army headquarters, which had insisted that the 1st Army keep closer to the western flank, rather than attack to the west of Mons. It was believed that only part of the BEF had been engaged and that there was a main line of defence from Valenciennes to Bavay, which Kluck ordered to be enveloped on 25 August.[63] The 1st Army was delayed by the British and suffered many casualties but crossed the barrier of the Mons–Condé Canal and began its advance into France. The Germans drove the BEF and French armies before them almost to Paris, before being stopped at the Battle of the Marne.[64]

Casualties

J. E. Edmonds, the British official historian, recorded "just over" 1,600 British casualties, most in the two battalions of the 8th Brigade which had defended the salient and wrote that German losses "must have been very heavy" as this explained German inertia after dark when the 8th Brigade was vulnerable, several other gaps existed in the British line and the retirement had begun.[65] John Keegan estimated German losses to have been c. 5,000 men.[66] In 1997, D. Lomas recorded German losses from 3,000 to 5,000 men.[67] In 2009, Herwig recorded 1,600 British casualties and c. 5,000 German casualties, despite the fact that Kluck and Kuhl did not reveal 1st Army casualties.[68] Post-war German records estimated 2,145 dead and missing and 4,932 wounded in the 1st Army from 20–31 August.[69] Using German regimental histories, Terence Zuber gave "no more than 2,000" German casualties.[70]

Legacy

The Battle of Mons has attained an almost mythic status. In British historical writing, it has a reputation as an unlikely victory against overwhelming odds, similar to the English victory at the Battle of Agincourt.[71] Mons gained two myths, the first being the a miraculous tale that the Angels of Mons—angelic warriors sometimes described as phantom longbowmen from Agincourt—had saved the British Army by halting the German troops. The second one was the Hound of Mons, which alleged a German scientist engineered a hellhound to be unleashed on British soldiers at night.[72][73]

Soldiers of the BEF who fought at Mons became eligible for a campaign medal, the 1914 Star, often colloquially called the Mons Star, honouring troops who had fought in Belgium or France 5 August – 22 November 1914. On 19 August 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm allegedly issued an Order of the Day which read in part: ". . . my soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English; walk over Field Marshal French's contemptible little Army." This led to the British "Tommies" of the BEF proudly labelling themselves "The Old Contemptibles". No evidence of the Order of the Day has been found in German archives and the ex-Kaiser denied giving it. According to the controversial book Falsehood in War-Time, an investigation conducted by General Frederick Maurice traced the origins of the Order to the British GHQ, where it had been concocted for propaganda purposes.[74]

The Germans established the St Symphorien Military Cemetery as a memorial to the German and British dead. On a mound in the centre of the cemetery, a grey granite obelisk 7 metres (23 ft) tall was built with a German inscription: "In memory of the German and English soldiers who fell in the actions near Mons on the 23rd and 24th August 1914."[75] Originally, 245 German and 188 British soldiers were interred at the cemetery. More British, Canadian and German graves were moved to the cemetery from other burial grounds and more than 500 soldiers were eventually buried in St. Symphorien, of which over 60 were unidentified. Special memorials were erected to five soldiers of the Royal Irish Regiment believed to be buried in unnamed graves. Other special memorials record the names of four British soldiers, buried by the Germans in Obourg Churchyard, whose graves could not be found. St. Symphorien cemetery also contains the graves of the two soldiers believed to be the first (Private John Parr, 4th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 21 August 1914) and the last (Private Gordon Price, 28th Canadian Infantry Regiment, 11 November 1918) Commonwealth soldiers to be killed during the First World War. A tablet in the cemetery sets out the gift of the land by Jean Houzeau de Lehaie.[76] A bronze tablet was erected on a wall of Obourg railway station, commemorating British soldiers who lost their lives around Obourg including an unnamed soldier who is said to have stayed behind at the cost of his own life, perched atop the station, in order to cover his withdrawing comrades.[77] The small portion of the wall supporting the plaque was preserved when the rest of the building was demolished in 1980.[78]

See also

- La Ferté-sous-Jouarre memorial

- HMS Mons, ships of the Royal Navy named in honour of the battle

- Order of battle at Mons

- Second Battle of Mons, the battle in November 1918 that liberated the area after four years of German occupation

Notes

- ^ Private Alhaji Grunshi of the Gold Coast Regiment of the West African Frontier Force, was also nominated as the first soldier of the British Army to have fired a rifle shot in the Great War, on 12 August 1914 at Togblekove, Togo (formerly Togoland), during the Togoland Campaign.[19]

Footnotes

- ^ Gordon 1917, p. 12.

- ^ Gordon 1917, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Lomas 1997, pp. 14, 62.

- ^ Gardner 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 3.

- ^ a b Lomas 1997, p. 28.

- ^ Zuber 2011b, pp. 95–97, 132–133.

- ^ a b c Hamilton 1916, p. 5.

- ^ Gordon 1917, p. 24.

- ^ Hastings 2013, p. 245.

- ^ Gordon 1917, p. 15.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, p. 430–431.

- ^ Lomas 1997, p. 34.

- ^ Lomas 1997, p. 55.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 6–7, 13.

- ^ "First casualty of the war". Watford Observer. 20 November 2003. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ "Irish soldiers involved in fighting at Mons". RTE. Boston College. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Opening Salvos". The First Shot: 22 August 1914. BBC. Archived from the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Hastings 2013, p. 244.

- ^ Lomas 1997, p. 19.

- ^ Tuchman 1962, p. 255.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 162.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 164, 172.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 173, 175, 215–217.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 14.

- ^ Bloem 2004, pp. 39, 41.

- ^ Gordon 1917, p. 32.

- ^ Tuchman 1962, p. 302.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, p. 76.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "No. 28976". The London Gazette. 13 November 1914. pp. 9373–9374.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 16.

- ^ Lomas 1997, p. 44.

- ^ Hastings 2013, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 25.

- ^ Mallinson 2013, fn23.

- ^ Reed, Paul. "Nimy August 1914". Old Front Line. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 26.

- ^ Hastings 2013, p. 255.

- ^ Ballard 2015[page needed]

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 28.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Gordon 1917, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Hamilton 1916, p. 32.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 216.

- ^ a b Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 222–224.

- ^ a b Humphries & Maker 2013, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Hoeppner 1994, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Raleigh 1969, pp. 298–304.

- ^ Lomas 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Reagan 1992, p. 89.

- ^ Lomas 1997, pp. 72, 83.

- ^ Holmes 1995, p. 260.

- ^ Tuchman 1962, pp. 306–307; Hamilton 1916, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Bloem 2004, p. 49.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 226.

- ^ Baldwin 1963, p. 25.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, p. 83.

- ^ Keegan 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Lomas 1997, p. 65.

- ^ Herwig 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Sanitäts 1934, p. 36.

- ^ Zuber 2011a, ch 4, para 237.

- ^ Tuchman 1962, pp. 306–307.

- ^ "It Hunted Men in No Man's Land - The Hound of Mons". Wartime Stories on Youtube. 24 December 2022. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Clarke 2005.

- ^ Ponsonby, Arthur: Falsehood in War-Time Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. 1928.

- ^ "St. Symphorien Military Cemetery". WW1 Cemeteries. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Cemetery Details – St Symphorien Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ "5. Obourg Station". visitMons - The Official Tourism Website of the Mons Region. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "La ligne manage Mons électrifiée ! - Rixke Rail's Archives". rixke.tassignon.be. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

References

Books

- Baldwin, Hanson (1963). World War I: An Outline History. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 464551794.

- Ballard, Colin R. (2015). Smith-Dorrien (3rd ed.). Pickle Partners. ISBN 978-1-78625-522-8. Archived from the original on 23 August 2024. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Bloem, W. (2004) [1916]. Vormarsch [The Advance from Mons 1914: The Experiences of a German Infantry Officer] (in German) (trans. Helion ed.). Bremen: Grethlein. ISBN 1-874622-57-4. Retrieved 30 November 2013 – via Archive Foundation.

- Clarke, David (2005). The Angel of Mons: Phantom Soldiers and Ghostly Guardians. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-86277-3.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Gardner, Nikolas (2003). Trial by Fire: Command and the British Expeditionary Force in 1914. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-32473-4.

- Gordon, George (1917). The Retreat from Mons. London: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1893352.

- Hamilton, E. (1916). The First Seven Divisions: Being a Detailed Account of the Fighting from Mons to Ypres. London: Hurst and Blackett. OCLC 3579926.

- Hastings, M. (2013). Catastrophe: Europe Goes to War 1914. London: Knopf Press. ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Hoeppner, E. W. von (1994) [1921]. Deutschlands Krieg in der Luft: ein Rückblick auf die Entwicklung und die Leistungen unserer Heeres-Luftstreitkräfte im Weltkriege [Germany's War in the Air: A Review on the Development and the Achievements of our Army Air Forces in the World War] (in German). Translated by Larned, J. Hawley (Battery Press ed.). Leipzig: K. F. Koehle. ISBN 0-89839-195-4.

- Holmes, Richard (1995). Riding the Retreat Mons to the Marne 1914 Revisited. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 32701390.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Keegan, John (2002). The First World War: An Illustrated History. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-8040-0.

- Lomas, D. (1997). Mons, 1914. Wellingborough: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-551-9.

- Mallinson, Alan (2013). 1914: Fight the Good Fight, Britain, the Army and the Coming of the First World War. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-44646-350-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Moberly, F. J. (1995) [1931]. Military Operations Togoland and the Cameroons 1914–1916. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-235-7.

- Raleigh, W. (1969) [1922]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. History of the Great War based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Hamish Hamilton ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-241-01805-6. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Reagan, Geoffrey (1992). Military Anecdotes. Guinness. ISBN 0-85112-519-0.

- Die Krankenbewegung bei dem Deutschen Feld-und Besatzungs-heer [Sick Persons' Whereabouts with the German Field and Occupying Army]. Sanitätsbericht über das Deutsche Heer (Deutsches Feld-und Besatzungs-heer) im Weltkriege 1914–1918 [Sanitations report about the German Army (German Field and Occupying Army) in the World War 1914–1918 (in German). Vol. III. Berlin: Mittler. 1934. OCLC 312555581.

- Tuchman, B. (1962). The Guns of August (2004 ed.). New York: Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-345-47609-8.

- Zuber, T. (2011a) [2010]. The Mons Myth. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7628-5.

- Zuber, T. (2011b). The Real German War Plan 1904–14. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75245-664-5.

Further reading

- Evans, Martin (2004). Battles of World War I. Select Editions. ISBN 1-84193-226-4.

- Herbert, Aubrey (2010). Mons, Anzac and Kut: A British Intelligence Officer in Three Theatres of the First World War, 1914–18. Leonaur. ISBN 978-0-85706-366-3.

- Hussey, A. H.; Inman, D. S. (2002) [1921]. The Fifth Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 1-84342-267-0. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Kluck, A. (1920). The March on Paris and the Battle of the Marne, 1914. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 2513009.

- Rinaldi, Richard A. (2008). Order of Battle of the British Army 1914. Takoma Park, MD: Tiger Lily Books. ISBN 978-0-98205-411-6.

- Ritter, G. (1956). Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth (PDF). Horsham, Sussex: Riband Books. OCLC 221684780. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- Terraine, J. (1960). Mons The Retreat to Victory. London: Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-240-9.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. Vol. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. ISBN 1-84342-207-7. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

Encyclopaedias

- Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia, M–R. Vol. 3. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

Journals