LIMSwiki

Contents

| Pasadena Freeway Part of Historic US Route 66 | |

Arroyo Seco Parkway highlighted in red | |

| Route information | |

| Maintained by Caltrans | |

| Length | 8.162 mi[1] (13.135 km) |

| History | Opened in 1940; renamed in 1954; name reverted in 2010 |

| Tourist routes | |

| Restrictions | No trucks over 3 tons (including buses, unless authorized by the California Public Utilities Commission)[2] |

| Major junctions | |

| South end | |

| North end | Glenarm Street in Pasadena |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Counties | Los Angeles |

| Highway system | |

| Southern California freeways | |

Arroyo Seco Parkway Historic District | |

| NRHP reference No. | 10001198[3] |

| Added to NRHP | February 17, 2011 |

The Arroyo Seco Parkway, also known as the Pasadena Freeway, is one of the oldest freeways in the United States. It connects Los Angeles with Pasadena alongside the Arroyo Seco seasonal river. Mostly opened in 1940, it represents the transitional phase between early parkways and later freeways. It conformed to modern standards when it was built, but is now regarded as a narrow, outdated roadway.[4] A 1953 extension brought the south end to the Four Level Interchange in downtown Los Angeles and a connection with the rest of the freeway system.

The road remains largely as it was on opening day, though the plants in its median have given way to a steel guard rail, and most recently to concrete barriers, and it now carries the designation State Route 110, not historic U.S. Route 66. Between 1954 and 2010, it was designated the Pasadena Freeway. In 2010, as part of plans to revitalize its scenic value and improve safety, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) restored the roadway's original name.[5] All of its original bridges remain, including four that predate the parkway itself, built across the Arroyo Seco before the 1930s. The road has a crash rate roughly twice the rate of other freeways, largely due to an outdated design lacking in acceleration and deceleration lanes.[6]

The Arroyo Seco Parkway is designated a State Scenic Highway, National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, and National Scenic Byway. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Route description

The six-lane Arroyo Seco Parkway (part of State Route 110) begins at the Four Level Interchange, a symmetrical stack interchange on the north side of downtown Los Angeles that connects the Pasadena (SR 110 north), Harbor (SR 110 south), Hollywood (US 101 north), and Santa Ana (US 101 south) Freeways. The first interchange is with the north end of Figueroa Street at Alpine Street, and the freeway then meets the north end of Hill Street at a complicated junction that provides access to Dodger Stadium. Beyond Hill Street, SR 110 temporarily widens to four northbound and five southbound lanes as it enters the hilly Elysian Park, where the northbound lanes pass through the four Figueroa Street Tunnels and the higher southbound lanes pass through a cut and over low areas on bridges. One interchange, with Solano Avenue and Amador Street, is located between the first and second tunnels. Just beyond the last tunnel is a northbound left exit and corresponding southbound right entrance for Riverside Drive and the northbound Golden State Freeway (I-5). Immediately after those ramps, the Arroyo Seco Parkway crosses a pair of three-lane bridges over the Los Angeles River just northwest of its confluence with the Arroyo Seco, one rail line on each bank, and Avenue 19 and San Fernando Road on the north bank. A single onramp from San Fernando Road joins SR 110 northbound as it passes under I-5, and a northbound left exit and southbound right entrance connect to the north segment of Figueroa Street. Here the original 1940 freeway, mostly built along the west bank of the Arroyo Seco, begins as the southbound lanes curve from their 1943 alignment over the Los Angeles River into the original alignment next to the northbound lanes.[7]

As the original freeway begins, it passes under an extension to the 1925 Avenue 26 Bridge, one of four bridges over the Arroyo Seco that predate the parkway's construction. A southbound exit and northbound entrance at Avenue 26 complement the Figueroa Street ramps, and similar ramps connect Pasadena to both directions of I-5. SR 110 continues northeast alongside the Arroyo Seco, passing under the A Line light rail and Pasadena Avenue before junctioning Avenue 43 at the first of many folded diamond interchanges that feature extremely tight (right-in/right-out) curves on the exit and entrance ramps. The next interchange, at Avenue 52, is a normal diamond interchange, and soon after is Via Marisol, where the northbound side has standard diamond ramps, but on the southbound side Avenue 57 acts as a folded diamond connection. The 1926 Avenue 60 Bridge is the second original bridge, and is another folded diamond, with southbound traffic using Shults and Benner Streets to connect. The 1895 Santa Fe Arroyo Seco Railroad Bridge (now A Line) lies just beyond, and after that is a half diamond interchange at Marmion Way/Avenue 64 with access towards Los Angeles only. After the freeway passes under the 1912 York Boulevard Bridge, the pre-parkway bridge, southbound connections between the freeway and cross street can be made via Salonica Street. As the Arroyo Seco curves north to pass west of downtown Pasadena, the Arroyo Seco Parkway instead curves east, crossing the stream into South Pasadena. A single northbound offramp on the Los Angeles side of the bridge curves left under the bridge to Bridewell Street, the parkway's west-side frontage road.[7]

As they enter South Pasadena, northbound motorists can see a "City of South Pasadena" sign constructed, in the late 1930s, of stones from the creek bed embedded in a hillside.[8] This final segment of the Arroyo Seco Parkway heads east in a cut alongside Grevelia Street, with a full diamond at Orange Grove Avenue and a half diamond at Fair Oaks Avenue. In between those two streets it crosses under the A Line for the third and final time. Beyond Fair Oaks Avenue, SR 110 curves north around the east side of Raymond Hill and enters Pasadena, where the final ramp, a southbound exit, connects to State Street for access to Fair Oaks Avenue. The freeway, and state maintenance,[1] ends at the intersection with Glenarm Street, but the six- and four-lane Arroyo Parkway, now maintained by the city of Pasadena, continues north as a surface road to Colorado Boulevard (historic U.S. Route 66) and beyond to Holly Street near the Memorial Park A Line station.[7]

Route usage

According to CalTrans in 2016, the average annual daily traffic (AADT) on the Arroyo Seco Parkway was 78,000 car trips at Orange Grove Blvd, 100,000 car trips at Ave 64, and 123,000 car trips at Ave 43.

History

Planning

The Arroyo Seco (Spanish: "dry gulch, or streambed") is an intermittent stream that carries rainfall from the San Gabriel Mountains southerly through western Pasadena into the Los Angeles River near downtown Los Angeles. During the dry season, it served as a faster wagon connection between the two cities than the all-weather road on the present Huntington Drive.[9]

The first known survey for a permanent roadway through the Arroyo was made by T. D. Allen of Pasadena in 1895, and in 1897 two more proposals were made, one for a scenic parkway and the other for a commuter cycleway. The latter was partially constructed and opened by Horace Dobbins, who incorporated the California Cycleway Company and bought a six-mile (10 km) right-of-way from downtown Pasadena to Avenue 54 in Highland Park, Los Angeles. Construction began in 1899, and about 1+1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) of the elevated wooden bikeway were opened on January 1, 1900, starting near Pasadena's Hotel Green and ending near the Raymond Hotel. The majority of its route is now Edmondson Alley; a toll booth was located near the north end, in the present Central Park. Due to the end of the bicycle craze of the 1890s and the existing Pacific Electric Railway lines connecting Pasadena to Los Angeles, the cycleway did not and was not expected to turn a profit, and never extended beyond the Raymond Hotel into the Arroyo Seco. Sometime before 1910, the structure was dismantled, and the wood sold for lumber,[10][11] and the Pasadena Rapid Transit Company, a failed venture headed by Dobbins to construct a streetcar line, acquired the right-of-way.[12][13]

Due to the rise of the automobile, most subsequent plans for the Arroyo Seco included a roadway, though they differed as to the purpose: some, influenced by the City Beautiful movement, concentrated on the park, while others, particularly those backed by the Automobile Club of Southern California (ACSC), had as their primary purpose a fast road connecting the two cities. The first plan that left the Arroyo Seco in South Pasadena to better serve downtown Pasadena was drawn up by Pasadena City Engineer Harvey W. Hincks in 1916 and supported by the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce and ACSC. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and Harland Bartholomew's 1924 Major Street Traffic Plan for Los Angeles, while concentrating on traffic relief, and noting that the Arroyo Seco Parkway would be a major highway, suggested that it be built as a parkway, giving motorists "a great deal of incidental recreation and pleasure". By the mid-1930s, plans for a primarily recreational parkway had been overshadowed by the need to carry large numbers of commuters.[14]

Debates continued on the exact location of the parkway, in particular whether it would bypass downtown Pasadena. In the late 1920s, Los Angeles acquired properties between San Fernando Road and Pasadena Avenue, and City Engineer Lloyd Aldrich began grading between Avenues 60 and 66 in the early 1930s. By June 1932, residents of Highland Park and Garvanza, who had paid special assessments to finance improvement of the park, became suspicious of what appeared to be a road, then graded along the Arroyo Seco's west side between Via Marisol (then Hermon Avenue) and Princess Drive. Merchants on North Figueroa Street (then Pasadena Avenue) also objected, due to the loss of business they would suffer from a bypass. Work stopped while the interested parties could work out the details, although, in late 1932 and early 1933, Aldrich was authorized to grade a cheaper route along the east side between Avenue 35 and Hermon Avenue. To the north, Pasadena and South Pasadena endorsed in 1934 what was essentially Hincks's 1916 plan, but lacked the money to build it. A bill was introduced in 1935 to add the route to the state highway system, and after some debate a new Route 205 was created as a swap for the Palmdale-Wrightwood Route 186,[15][16] as the legislature had just greatly expanded the system in 1933, and the California Highway Commission opposed a further increase.[17]

Construction

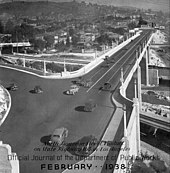

To connect the proposed parkway with downtown Los Angeles, that city improved and extended North Figueroa Street as a four-lane road to the Los Angeles River, allowing drivers to bypass the congested North Broadway Bridge on the existing but underutilized Riverside Drive Bridge. A large part of the project lay within Elysian Park, and four Art Deco tunnels were built through the hills. The first three, between Solano Avenue and the river, opened in late 1931,[18] and the fourth opened in mid-1936,[19] completing the extension of Figueroa Street to Riverside Drive. As with the contemporary Ramona Boulevard east from downtown, grade separations were mostly built only where terrain dictated. For Figueroa Street, this meant that all crossings except College Street (built several years after the extension was completed[20]), where a hill was cut through, were at grade.[21] The Figueroa Street Viaduct, connecting the Riverside Drive intersection with North Figueroa Street (then Dayton Avenue) across the Los Angeles River, opened in mid-1937.[22] Closer to downtown, an interchange was built at Temple Street in 1939.[23][24]

Although many South Pasadena residents opposed the division of the city that the parkway would bring, the city's voters elected supporters in the 1936 elections. The state, which had the power to put the road where it wished even had South Pasadena continued to oppose it, approved the route on April 4, 1936. The route used the Arroyo Seco's west bank to near Hough Street, where it crossed to the east and cut through South Pasadena to the south end of Broadway (now Arroyo Parkway) in Pasadena. Another project, the Arroyo Seco Flood Control Channel, was built by the Works Progress Administration before and during construction of the parkway to avoid damages from future floods. A number of state engineers toured East Coast roads in early 1938, including Chicago's Lake Shore Drive, full and modified cloverleaf interchanges in Massachusetts and New Jersey, and Robert Moses's parkway system in New York City. The parkway was the first road built in California under a 1939 freeway law that allowed access to be completely limited to a number of specified points. Although, in some areas, it was possible to use a standard diamond interchange, other locations required folded diamonds, or, as the engineers called them, "compressed cloverleafs", where local streets often took the place of dedicated ramps, ending at the parkway with a sharp right turn required to enter or exit. The highway was designed with two 11–12-foot (3.4–3.7 m) lanes and one 10-foot (3.0 m) shoulder in each direction, with the wider inside (passing) lanes paved in black asphalt concrete and the outside lanes paved in white Portland cement concrete. The differently-colored lanes would encourage drivers to stay in their lanes. (By mid-1939, the state had decided to replace the shoulders with additional travel lanes for increased capacity; except on a short piece in South Pasadena, these were also paved with Portland cement. So that disabled vehicles could be safely removed from the roadway, about 50 "safety bays" were constructed in 1949 and 1950.[25]) The engineers used a design speed of 45 miles per hour (72 kilometres per hour), superelevating curves where necessary to accomplish this. (The road is now posted at 55 mph (89 km/h).[26]) Despite the freeway design, many parkway characteristics were incorporated, such as plantings of mostly native flora alongside the road.[27]

Prior to parkway construction, nine roads and two rail lines crossed the Arroyo Seco and its valley on bridges, and a number of new bridges were built as part of the project. Only four of the existing bridges were kept, albeit with some changes:[28][29][30] the 1925 Avenue 26 Bridge, the 1926 Avenue 60 Bridge, the 1895 Santa Fe Arroyo Seco Railroad Bridge (now part of the A Line (Los Angeles Metro)) near Avenue 64, and the 1912 York Boulevard Bridge. The Avenue 43 Bridge would have been kept had the Los Angeles Flood of 1938 not destroyed it. At Cypress Avenue, abutments and a foundation were built for a roadway, but were not used until the 1960s, when a pedestrian bridge was built as part of the Golden State Freeway (I-5) interchange project.[28] In South Pasadena, seven streets and the Union Pacific and Santa Fe railroad lines on a double track combined bridge were carried over the parkway to keep the communities on each side connected.[31]

Construction on the Arroyo Seco Parkway, designed under the leadership of District Chief Engineer Spencer V. Cortelyou and Design Engineer A. D. Griffin, began with a groundbreaking ceremony in South Pasadena on March 22, 1938, and generally progressed from Pasadena southwest. The first contract, stretching less than a mile (1.5 km) from Glenarm Street in Pasadena around Raymond Hill to Fair Oaks Avenue in South Pasadena, and including no bridges, was opened to traffic on December 10, 1938. A 3.7-mile (6.0 km) section opened on July 20, 1940, connecting Orange Grove Avenue in South Pasadena with Avenue 40 in Los Angeles.[32] The remainder in Los Angeles, from Avenue 40 southwest to the Figueroa Street Viaduct at Avenue 22, was dedicated on December 30, 1940, with great fanfare, and opened to the public the following day in time for the Tournament of Roses Parade and Rose Bowl on New Year's Day.[33] However, the highway through South Pasadena was not completed until January 30, 1941, and landscaping work continued through September. The final cost of $5.75 million, under $1 million per mile, was extremely low for a freeway project because the terrain was favorable for grade separations.[34]

The state began upgrading the four-lane North Figueroa Street extension (then part of Route 165) in October 1940 as a "Southerly Extension" of the parkway, even before the parkway was complete. The at-grade intersection with Riverside Drive was already a point of congestion, and the six lanes of parkway narrowing into four lanes of surface street would cause much greater problems. The two-way Figueroa Street Tunnels and Viaduct were repurposed for four lanes of northbound traffic, and a higher southbound roadway was built to the west. From the split with Hill Street south to near the existing College Street overpass, the four-lane surface road became a six-lane freeway. The extension was designed almost entirely on freeway, rather than parkway, principles, as it had to be built quickly to handle existing traffic. The new road split from the old at the Figueroa Street interchange, just south of Avenue 26, and crossed the Los Angeles River and the northbound access to Riverside Drive on a new three-lane bridge. Through Elysian Park, a five-lane open cut was excavated west of the existing northbound tunnel lanes, saving about $1 million. The extension, still feeding into surface streets just south of College Street, was opened to traffic on December 30, 1943, again allowing its use for the New Year's Day festivities.[35]

While the Arroyo Seco Parkway was being built and extended, the region's freeway system was taking shape. The short city-built Cahuenga Pass Freeway opened on June 15, 1940,[36] over a month before the second piece of the Arroyo Seco Parkway was complete. In the next two decades, the Harbor, Hollywood (Cahuenga Pass), Long Beach (Los Angeles River), San Bernardino (Ramona), and Santa Ana Freeways were partially or fully completed to their eponymous destinations, and others were under construction.[37] The centerpiece of the system was the Four Level Interchange just north of downtown Los Angeles, the first stack interchange in the world. Although it was completed in 1949, the structure was not fully used until September 22, 1953, when the short extension of the Arroyo Seco Parkway to the interchange opened. Though the common name used by the public had become "Arroyo Seco Freeway" over the years, it was officially a "Parkway" until November 16, 1954, when the California Highway Commission changed its name to the Pasadena Freeway.[38]

Beginning in June 2010, the state began modifying interchange signs to remove the Pasadena Freeway name and reinstate the Arroyo Seco Parkway name. Signs that indicate route 110 as a "freeway" are being modified to "parkway" or its "Pkwy" abbreviation.

Post-construction

Despite a quadrupling of traffic volumes, the original roadway north of the Los Angeles River largely remains as it was when it opened in 1940. Trucks and buses were banned in 1943, though the bus restriction has since been dropped; this has kept the freeway in good condition. Except for the Golden State Freeway (I-5) interchange near the river, completed in 1962, the few structural changes to the freeway north of the river include the closure of the original southbound exit to Fair Oaks Avenue after its location on a curve proved dangerous[11] and the replacement of shrubs in the 4-foot (1.2 m) median with a steel and now concrete guard rail. Los Angeles paid for reconstruction of the interchange at Hill Street, south of Elysian Park, in the early 1960s to serve the new Dodger Stadium.[39] An interchange with Amador Street once had both left and right exits and entrances, it now only has a right exit and entrance.

The parkway's design is now outdated, and includes tight "right-in/right-out" access with a recommended exit speed of 5 miles per hour (8.0 km/h) and stop signs on the entrance ramps.[citation needed] There are no acceleration or deceleration lanes, meaning that motorists must attempt to merge immediately into freeway traffic from a complete stop.[40] While the curves are banked for higher speeds, they were designed at half the modern standard. A three-year Caltrans study determined that the parkway has a crash rate that is twice that of comparable highways, with the primary factor being the lack of acceleration and deceleration lanes.[6] LAist noted that many motorists find the act of merging onto the parkway to be "terrifying".[40]

The Arroyo Seco Parkway was the first freeway in the Western United States.[41] It became a new alignment of U.S. Route 66, and the old routing via Figueroa Street and Colorado Boulevard became U.S. Route 66 Alternate.[42] The southern extension over the Los Angeles River to downtown Los Angeles also carried State Route 11 (which remained on the old route when US 66 was moved) and U.S. Routes 6 and 99 (which followed Avenue 26 and San Fernando Road to the northwest).[43] The 1964 renumbering saw US 66 truncated to Pasadena, and SR 11 was moved from Figueroa Street (which became SR 159) to the Pasadena Freeway.[44] Finally, the number was changed to SR 110 in 1981, when SR 11 between San Pedro and the Santa Monica Freeway (I-10) became I-110.[45]

Despite its flaws, the Arroyo Seco Parkway remains the most direct car route between downtown Los Angeles and Pasadena; the only freeway alternate (which trucks must use) is the Glendale Freeway (SR 2) to the northwest. (LA Metro's A Line [formerly the Gold Line] provides light rail service along the former Santa Fe Railway line.) The state legislature designated the original section of the Parkway, north of the Figueroa Street Viaduct, as a "California Historic Parkway" (part of the State Scenic Highway System reserved for freeways built before 1945) in 1993;[46] the only other highway so designated is the Cabrillo Freeway (SR 163) in San Diego. The American Society of Civil Engineers named it a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1999,[47] and it became a National Scenic Byway in 2002[48] and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.[3] Occidental College hosted the "ArroyoFest Freeway Walk and Bike Ride" on Sunday, June 15, 2003, closing the freeway to motor vehicles to "highlight several ongoing or proposed projects within the Arroyo that can improve the quality of life for everyone in the area".[49] The event was held again twenty years later, in October 2023.[50] Over 50,000 attended the event.[51]

Exit list

Mileage is measured from Route 110's southern terminus in San Pedro. The entire route is in Los Angeles County.

| Location | mi[52][53] | km | Exit[52] | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | 23.76 | 38.24 | – | Continuation beyond US 101 | |

| 24A | Four Level Interchange; US 101 north exit 3, south exit 3B | ||||

| 24.49 | 39.41 | 24B | Sunset Boulevard | Southbound exit and northbound entrance | |

| 24.66 | 39.69 | 24C | Hill Street – Chinatown, Civic Center | No southbound entrance; signed as exit 24B northbound; left exit southbound | |

| 24D | Stadium Way – Dodger Stadium | Signed as exit 24B northbound | |||

| 24.90 | 40.07 | Figueroa Street Tunnel No. 1 (northbound) | |||

| 25.02 | 40.27 | 25 | Solano Avenue / Academy Road | ||

| 25.14– 25.37 | 40.46– 40.83 | Figueroa Street Tunnels No. 2-4 (northbound) | |||

| 25.68 | 41.33 | 26A | Northbound left exit and southbound entrance; I-5 south exit 137B | ||

| 25.71 | 41.38 | 26B | Figueroa Street | Northbound left exit and southbound entrance; former SR 159 | |

| 25.84 | 41.59 | 26A | Avenue 26 | Southbound exit and northbound entrance; former SR 163 | |

| 26B | Southbound exit and northbound entrance; I-5 north exit 137B, south exit 137A | ||||

| 27.05 | 43.53 | 27 | Avenue 43 | ||

| 27.98 | 45.03 | 28A | Avenue 52 | ||

| 28.31 | 45.56 | 28B | Via Marisol | Formerly Hermon Avenue | |

| 28.69 | 46.17 | 29 | Avenue 60 | ||

| 29.43 | 47.36 | 30A | Marmion Way / Avenue 64 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance | |

| 30 | York Boulevard | Southbound exit and entrance | |||

| 30.01 | 48.30 | 30B | Bridewell Street | Northbound exit only | |

| South Pasadena | 30.52 | 49.12 | 31A | Orange Grove Avenue | |

| 31.10 | 50.05 | 31B | Fair Oaks Avenue – South Pasadena | No northbound entrance | |

| Pasadena | 31.84 | 51.24 | Northern terminus of freeway and state maintenance | ||

| 31.91 | 51.35 | – | Glenarm Street | At-grade intersection | |

| 32.47 | 52.26 | – | California Boulevard | At-grade intersection | |

| 33.05 | 53.19 | – | At-grade intersection | ||

| 33.15 | 53.35 | – | Colorado Boulevard | At-grade intersection; former SR 248 | |

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

See also

References

- ^ a b California Department of Transportation. "State Truck Route List". Sacramento: California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Legal Truck Size & Weight Work Group (March 2, 2011). "Special Route Restriction History: Route 110". Sacramento: California Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ a b National Park Service (February 4, 2011). "National Register of Historic Places Weekly Action List". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ *Gruen, J. Philip & Lee, Portia (August 1999). Arroyo Seco Parkway (HAER No. CA-265) (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 4–5. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ Pool, Bob (June 25, 2010). "Pasadena Freeway Getting a New Look and a New Name". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Stein, William J.; Neuman, Timothy R. (July 2007). "Case Study 4: State Route 110 (The Arroyo Seco Parkway)". Mitigation Strategies For Design Exceptions (PDF) (Report). Federal Highway Administration. p. 146. FHWA-SA-07-011.

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) conducted a 3-year crash analysis for the corridor. The data indicated a crash rate about twice the average rate for similar highway types. There were 1,217 total crashes over this time period. Of these, 324 crashes involved the median barrier, resulting in 111 injuries and 1 fatality. The analysis also showed concentrations of crashes at entrance and exit ramps and concluded that a primary causal factor is the limited acceleration and deceleration lengths.

- ^ a b c Google & United States Geological Survey. Street Maps and Topographic Maps (Map). ACME Mapper. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

{{cite map}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 9, 51.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Scheid, Ann (2006). Downtown Pasadena's Early Architecture. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-7385-3024-6.

- ^ a b Thomas, Rick R. (2007). South Pasadena. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 60–65. ISBN 978-0-7385-4748-0.

- ^ "Dash into Pasadena in Twelve Minutes". Los Angeles Times. January 1, 1909. p. II1.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 17–18, 23.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 18–26.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to add section 612 to, and to repeal section 486 of, the Streets and Highways Code, relating to secondary State highways". Fifty-first Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 426 p. 288, 1480. "A new route or portion of route is hereby added to the State highway system from Route 165 [Figueroa Street] near Los Angeles River in Los Angeles to Route 161 [Colorado Boulevard] in Pasadena at Broadway Avenue."

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to amend sections 251, 308, 340, 344, 351, 352, 361, 368, 369, 374, 377, 404 and 425 of, to add four two sections to be numbered 503, 504, 505 and 506 to, and to repeal sections 603, 611..." Fifty-second Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 841 p. 2361. "Route 205 is from Route 165 near Los Angeles River in Los Angeles to Route 161 in Pasadena at Broadway Avenue."

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 29–34.

- ^ "By-pass Route Through Elysian Park Tunnels Opened to Automobile Traffic". Los Angeles Times. November 1, 1931. p. E1.

- ^ "Shaw Opens New Tunnel". Los Angeles Times. August 5, 1936. p. A1.

- ^ "Street Job Bids Will Be Opened". Los Angeles Times. August 15, 1938. p. A10.

- ^ Prejza, Paul (donor) (1940). Aerial view of Chavez Ravine in Los Angeles, looking west, ca. 1940 (Photograph). Los Angeles: University of Southern California Libraries Digital Archive. chs-m2270. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ "New Bridge Dedicated". Los Angeles Times. July 7, 1937. p. A2.

- ^ "Traffic Project Work Pushed". Los Angeles Times. May 11, 1939. p. A1.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 27–28, 53–54.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 60, 69.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), p. 68.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 34–51.

- ^ a b California Department of Transportation (July 2015). "Log of Bridges on State Highways". Sacramento: California Department of Transportation.

- ^ Traffic and Vehicle Data Systems Unit (2006). "All Traffic Volumes on CSHS". California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ National Bridge Inventory database, 2006[full citation needed]

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 51–55.

- ^ "New Highway Opens Saturday". Los Angeles Times. July 17, 1940. p. A12.

- ^ "History of the Arroyo Seco Parkway Preserved in Museum's Archives". Pasadena Museum of History. April 11, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 55–59.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 59–64.

- ^ City of Los Angeles (December 22, 2005). "Cahuenga Parkway" (PDF). Transportation Topics & Tales. City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ^ Rand McNally (1959). Los Angeles and Vicinity (Map). Chicago: Rand McNally. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 64–67.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), pp. 67–72.

- ^ a b Washington, Aaricka (February 7, 2024). "Yes, Merging Onto The 110's Arroyo Seco Parkway Is Terrifying. We Have Pictures And Stories". LAist. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ Fisher, Jay (August 15, 2008). "Shabby Road: The Ills and Charms of California's First Freeway". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Faigin, Daniel P. "Correspondence between the Division of Highways and American Association of State Highway Officials". California Highways. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ California Division of Highways (1944). Los Angeles and Vicinity (Map). Sacramento: California Division of Highways. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011 – via American Roads.

- ^ "Route Renumbering: New Green Markers Will Replace Old Shields". California Highways and Public Works. Vol. 43, no. 3–4. March–April 1964. pp. 11–13. ISSN 0008-1159. Retrieved March 8, 2012 – via Archive.org.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to amend...the Streets and Highways Code, relating to state highways". 1981–1982 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 292 p. 1418. "Route 110 is from San Pedro to Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena."

- ^ California State Assembly. "An act to add Sections 280, 281, 282, and 283 to the Streets and Highways Code, relating to highways". 1993–1994 Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 179.

- ^ Gruen & Lee (1999), p. 4.

- ^ Irving, Lori (June 13, 2002). "U.S. Transportation Secretary Mineta Names 36 New National Scenic Byways, All-American Roads" (Press release). Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". ArroyoFest. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ^ "Cyclists took over the 110 Freeway: Here's what they had to say biking in LA". Los Angeles Times. October 29, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Tens of thousands take to the 110 Freeway for ArroyoFest event". Pasadena Star News. October 29, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Chand, AS (August 26, 2016). "Interstate and State Route 110 Freeway Interchanges" (PDF). California Numbered Exit Uniform System. California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Traffic and Vehicle Data Systems Unit (2002). "All Traffic Volumes on CSHS". California Department of Transportation.[permanent dead link]

External links

- Caltrans: Arroyo Seco Parkway highway conditions

- Caltrans Traffic Conditions Map

- California Highway Patrol Traffic Incidents

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-265, "Arroyo Seco Parkway", 41 photos, 1 color transparency, 22 measured drawings, 86 data pages, 6 photo caption pages

- California Department of Transportation: Route 110 Photo Album

- National Scenic Byways: Arroyo Seco Historic Parkway – Route 110

- Primary Resources – Metro Digital Resources Library: "Arroyo Seco Parkway At 70: The Unusual History Of The "Pasadena Freeway," California Cycleway & Rare Traffic Plan Images"

- Arroyo Seco Foundation (environmental preservation group focused on the Arroyo Seco, including information about the parkway)

- Mark's Highway Page: Pasadena Freeway (many current and several historic photos)

- Travel times

- American Society of Civil Engineers – National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark