LabLynx Wiki

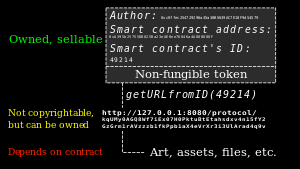

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a unique digital identifier that is recorded on a blockchain and is used to certify ownership and authenticity. It cannot be copied, substituted, or subdivided.[1] The ownership of an NFT is recorded in the blockchain and can be transferred by the owner, allowing NFTs to be sold and traded. Initially pitched as a new class of investment asset, by September 2023, one report claimed that over 95% of NFT collections had zero monetary value.[2][3]

NFTs can be created by anybody and require few or no coding skills to create. NFTs typically contain references to digital files such as artworks, photos, videos, and audio. Because NFTs are uniquely identifiable, they differ from cryptocurrencies, which are fungible (hence the name non-fungible token).

Proponents claim that NFTs provide a public certificate of authenticity or proof of ownership, but the legal rights conveyed by an NFT can be uncertain. The ownership of an NFT as defined by the blockchain has no inherent legal meaning and does not necessarily grant copyright, intellectual property rights, or other legal rights over its associated digital file. An NFT does not restrict the sharing or copying of its associated digital file and does not prevent the creation of NFTs that reference identical files.

NFT trading increased from US$82 million in 2020 to US$17 billion in 2021.[4] NFTs have been used as speculative investments and have drawn criticism for the energy cost and carbon footprint associated with some types of blockchain, as well as their use in art scams.[5] The NFT market has also been compared to an economic bubble or a Ponzi scheme.[6] At their peak, the three biggest NFT platforms were Ethereum, Solana, and Cardano.[7] In 2022, the NFT market collapsed; a May 2022 estimate was that the number of sales was down over 90% compared to 2021.[8]

Characteristics

An NFT is a data file, stored on a type of digital ledger called a blockchain, which can be sold and traded.[9] The NFT can be associated with a particular asset – digital or physical – such as an image, art, music, or recording of a sports event.[10] It may confer licensing rights to use the asset for a specified purpose.[11] An NFT (and, if applicable, the associated license to use, copy, or display the underlying asset) can be traded and sold on digital markets.[12] However, the extralegal nature of NFT trading usually results in an informal exchange of ownership over the asset that has no legal basis for enforcement,[13] and so often confers little more than use as a status symbol.[14]

NFTs function like cryptographic tokens, but unlike cryptocurrencies, NFTs are not usually mutually interchangeable, so they are not fungible.[a] A non-fungible token contains data links, for example which point to details about where the associated art is stored, that can be affected by link rot.[16]

Copyright

An NFT solely represents a proof of ownership of a blockchain record and does not necessarily imply that the owner possesses intellectual property rights to the digital asset the NFT purports to represent.[17][18][19] Someone may sell an NFT that represents their work, but the buyer will not necessarily receive copyright to that work, and the seller may not be prohibited from creating additional NFT copies of the same work.[20][21] According to legal scholar Rebecca Tushnet, "In one sense, the purchaser acquires whatever the art world thinks they have acquired. They definitely do not own the copyright to the underlying work unless it is explicitly transferred."[22]

Certain NFT projects, such as Bored Apes, explicitly assign intellectual property rights of individual images to their respective owners.[23] The NFT collection CryptoPunks was a project that initially prohibited owners of its NFTs from using the associated digital artwork for commercial use, but later allowed such use upon acquisition by the collection's parent company.[24]

History

Early projects

The first known "NFT", Quantum,[25] was created by Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash in May 2014. It consists of a video clip made by McCoy's wife, Jennifer. McCoy registered the video on the Namecoin blockchain and sold it to Dash for $4, during a live presentation for the Seven on Seven conferences at the New Museum in New York City. McCoy and Dash referred to the technology as "monetized graphics".[26] This explicitly linked a non-fungible, tradable blockchain marker to a work of art, via on-chain metadata (enabled by Namecoin).[27]

In October 2015, the first NFT project, Etheria, was launched and demonstrated at DEVCON 1 in London, Ethereum's first developer conference, three months after the launch of the Ethereum blockchain. Most of Etheria's 457 purchasable and tradable hexagonal tiles went unsold for more than five years until March 13, 2021, when renewed interest in NFTs sparked a buying frenzy. Within 24 hours, all tiles of the current version and a prior version, each hardcoded to 1 ETH (US$0.43 at the time of launch), were sold for a total of US$1.4 million.[28]

In 2016, Rare Pepes a "semi-fungible" NFT project centered around the Pepe the Frog meme involving a collective of artists contributing their works into a curated directory, emerged on Bitcoin through a protocol known as Counterparty (which had been created in 2014 and used to create other assets).[29]

In 2017, several NFT projects emerged on Ethereum that utilized a "fungible" token standard known as ERC-20. Curio Cards in May of that year is credited with being Ethereum's first art NFT project using the fungible standard and features artwork in the shape of a card among a variety of image types including satirized corporate logos[30] The generative art project of 10,000 pixelated characters known as CryptoPunks emerged soon after in June and would later establish itself as one of the most commercially successful NFT projects.[31] In December, a clipart based collection featuring images of rocks called EtherRock emerged.[32]

in November 2017, the widely acclaimed blockchain game on Ethereum known as CryptoKitties launched and is credited with pioneering what is considered to be the first bona fide non-fungible token standard, known as ERC-721.[33] It used an early version of ERC-721 that differed from the formally published version of the standard in 2018.[34]

ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard

While experiments around non-fungibility have existed on blockchains since as early as 2012 with Colored Coins on Bitcoin,[35] a community-driven paper called ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard was published in 2018 under the initiative of civic hacker and lead author William Entriken[36] and is recognized as pioneering the foundation for NFTs and enabling the growth of the wider eco-system.[37] It introduced the formalization and defining of the term Non-Fungible Token "NFT" in blockchain nomenclature by establishing a standard for smart contracts known as "ERC-721" whose tokens would have unique attributes and ownership details, ensuring no two tokens are alike.[38] The creation of derivative standards followed from its influence on Ethereum (like ERC-1155 enabling semi-fungibility) and other blockchains.[39] Its versatility enabled the pioneering of numerous use cases, including digital artwork, deeds to physical items, real estate (including virtual), access passes, and game assets.[40] Ultimately, the emergence of ERC-721 is recognized for having fundamentally changed the landscape of digital verification, authentication, and ownership.[41]

Origins of the term "NFT" and its adoption

The term NFT, prior to the blockchain game CryptoKitties' adoption of ERC-721, is not known to have been used for earlier projects.[42] Through discussion among stakeholders for the ERC-721 draft, the word deed was given consideration among other alternatives including distinguishable asset, title, token, asset, equity, ticket.[43] Ultimately, through Entriken's initiative under the moniker "Fulldecent," a vote was held during the paper's drafting phase to decide which word would be used in the published version and "NFT" was chosen by the stakeholders.[44]

The term "NFT" and the awareness of the ERC-721 standard received significant exposure and adopted use through the popularity of CryptoKitties in 2017.[42] While using the standard, CryptoKitties earned the recognition of being the first mainstream NFT dApp;[45] the game's usage was significant enough to have overwhelmed Ethereum's processing power at the time.[46]

Influence

During the height of the breakout success of CryptoKitties and the emergence of ERC-721 tokens in 2017, an NFT marketplace called OpenSea emerged to capitalize off of the new non-fungible token standard.[47] It positioned itself early in the NFT market landscape and grew to a $1.4 billion market cap in 2021 during the then-ongoing NFT boom.[48]

In 2021, ArtReview's Power 100 ranked ERC-721 at the #1 spot, praising it as "the most powerful art entity in the world" for creating a new kind of market for artworks that deviated from traditional gatekeeping norms and ushered in a different kind of collector.[49] Artist Beeple sold an ERC-721 NFT of his composite artwork known as Everydays: The First 5000 Days at Christie's for $69 million and was the first instance of a legacy arthouse dealing in NFTs.[50]

General NFT market

The NFT market experienced rapid growth during 2020, with its value tripling to US$250 million.[51] In the first three months of 2021, more than US$200 million were spent on NFTs.[52]

In the early months of 2021, interest in NFTs increased after a number of high-profile sales and art auctions.[53]

In May 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that the NFT market was "collapsing". Daily sales of NFT tokens had declined 92% from September 2021, and the number of active wallets in the NFT market fell 88% from November 2021. While rising interest rates had impacted risky bets across the financial markets, the Journal said "NFTs are among the most speculative."[8]

In December 2022, a programmer named Casey Rodarmor introduced a new way to add NFTs to the Bitcoin blockchain called "ordinals". By February 2023, the popularity of ordinals had led to an increase in bitcoin's payment fees and may have also partially contributed to an increase in bitcoin's price.[54]

A September 2023 report from cryptocurrency gambling website dappGambl claimed 95% of NFTs had fallen to zero monetary value.[2][3]

Uses

Commonly associated files

NFTs have been used to exchange digital tokens that link to a digital file asset. Ownership of an NFT is often associated with a license to use such a linked digital asset but generally does not confer the copyright to the buyer. Some agreements only grant a license for personal, non-commercial use, while other licenses also allow commercial use of the underlying digital asset.[55] This kind of decentralized intellectual copyright poses an alternative to established forms of safeguarding copyright controlled by state institutions and middlemen within the respective industry.[56]

Digital art

Digital art is a common use case for NFTs.[57] High-profile auctions of NFTs linked to digital art have received considerable public attention; the first such major house auction took place at Christie's in 2021.[58] The work entitled Merge by artist Pak was the most expensive NFT, with an auction price of US$91.8 million[59] and Everydays: the First 5000 Days, by artist Mike Winkelmann (known professionally as Beeple) the second most expensive at US$69.3 million in 2021.[12][60]

Some NFT collections, including Bored Apes, EtherRocks, and CryptoPunks, are examples of generative art, where many different images are created by assembling a selection of simple picture components in different combinations.[61]

In March 2021, the blockchain company Injective Protocol bought a $95,000 original screen print entitled Morons (White) from English graffiti artist Banksy and filmed somebody burning it with a cigarette lighter. They uploaded (known as "minting" in the NFT scene) and sold the video as an NFT.[62][63] The person who destroyed the artwork, who called themselves "Burnt Banksy", described the act as a way to transfer a physical work of art to the NFT space.[63]

American curator and art historian Tina Rivers Ryan, who specializes in digital works, said that art museums are widely not convinced that NFTs have "lasting cultural relevance."[64] Ryan compares NFTs to the net art fad before the dot-com bubble.[65][66] In July 2022, after the controversial sale of Michelangelo's Doni Tondo in Italy, the sale of NFT reproductions of famous artworks was prohibited in Italy. Given the complexity and lack of regulation of the matter, the Ministry of Culture of Italy temporarily requested that its institutions refrain from signing contracts involving NFTs.[67]

No centralized means of authentication exists to prevent stolen and counterfeit digital works from being sold as NFTs, although auction houses like Sotheby's, Christie's, and various museums and galleries worldwide started collaborations and partnerships with digital artists such as Refik Anadol, Dangiuz and Sarah Zucker.

NFTs associated with digital artworks could be sold and bought via NFT platforms. OpenSea, launched in 2017, was one of the first marketplaces to host various types of NFTs.[68][69] In July 2019, the National Basketball Association, the NBA Players Association and Dapper Labs, the creator of CryptoKitties, started a joint venture NBA Top Shot for basketball fans that let users buy NFTs of historic moments in basketball.[70][71] In 2020, Rarible was found, allowing multiple assets. In 2021, Rarible and Adobe formed a partnership to simplify the verification and security of metadata for digital content, including NFTs.[68] In 2021, a cryptocurrency exchange Binance, launched its NFT marketplace.[72] In 2022, eToro Art by eToro was founded, focusing on supporting NFT collections and emerging creators.[68][73]

Sotheby's and Christie's auction houses showcase artworks associated with the respective NFTs both in virtual galleries and physical screens, monitors, and TVs.[74][75][76]

Mars House, an architectural NFT created in May 2020 by artist Krista Kim, sold in 2021 for 288 Ether (ETH) — at that time equivalent to US$524,558.[77]

Games

NFTs can represent in-game assets. Some commentators describe these as being controlled "by the user" instead of the game developer[78] if they can be traded on third-party marketplaces without permission from the game developer. Their reception from game developers, though, has been generally mixed, with some like Ubisoft embracing the technology but Valve and Microsoft formally prohibiting them.[79]

- CryptoKitties was an early successful blockchain online game in which players adopt and trade virtual cats. The monetization of NFTs within the game raised a $12.5 million investment, with some kitties selling for over $100,000 each.[80][81][82][83] Following its success, CryptoKitties was added to the ERC-721 standard, which was created in January 2018 (and finalized in June).[84][85]

- In October 2021, Valve Corporation banned applications from their Steam platform if those applications use blockchain technology or NFTs to exchange value or game artifacts.[86]

- In December 2021, Ubisoft announced Ubisoft Quartz, "an NFT initiative which allows people to buy artificially scarce digital items using cryptocurrency". The announcement was heavily criticized by audiences, with the Quartz announcement video attaining a dislike ratio of 96% on YouTube. Ubisoft subsequently unlisted the video from YouTube.[87][88] The announcement was also criticized internally by Ubisoft developers.[89][90][91] The Game Developers Conference's 2022 annual report stated that 70 percent of developers surveyed said their studios had no interest in integrating NFTs or cryptocurrency into their games.[92][93]

- Some luxury brands minted NFTs for online video game cosmetics.[94] In November 2021, investment firm Morgan Stanley published a note claiming that this could become a US$56 billion market by 2030.[95]

- In July 2022, Mojang Studios announced that NFTs would not be permitted in Minecraft, saying that they went against the game's "values of creative inclusion and playing together".[96]

Music and film

NFTs have been proposed for use within the film-industry as a way to tokenize movie-scenes and sell them as collectibles in the form of NFTs.[97] Artists involved in the entertainment-industry can seek royalties through NFTs.[98] So far, NFTs have often been used in both the music- as well as the film-industry.

- In May 2018, 20th Century Fox partnered with Atom Tickets and released limited-edition Deadpool 2 digital posters to promote the film. They were available from OpenSea and the GFT exchange.[99]

- In March 2021, Adam Benzine's 2015 documentary Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah became the first motion picture and documentary film to be auctioned as an NFT.[100]

- Other examples of NFTs being used in the film-industry include a collection of NFT-artworks for Godzilla vs. Kong,[101] the release of both Kevin Smith's horror-movie KillRoy Was Here, and the 2021 film Zero Contact as NFTs in 2021.[102]

- In April 2021, an NFT was released for the score of the movie Triumph, composed by Gregg Leonard.[103]

- In November 2021, film director Quentin Tarantino released seven NFTs based on uncut scenes of Pulp Fiction. Miramax subsequently filed a lawsuit claiming that their film rights were violated and that the original 1993 contract with Tarantino gave them the right to mint NFTs in relation to Pulp Fiction.[104]

- In August 2022, Muse released album Will of the People as 1,000 NFTs; it became the first album for which NFT sales would qualify for the UK and Australian charts.[105][106]

By February 2021, NFTs accounted for US$25 million of revenue generated through the sale of artwork and songs as NFTs.[107] On February 28, 2021, electronic dance musician 3lau sold a collection of 33 NFTs for a total of US$11.7 million to commemorate the three-year anniversary of his Ultraviolet album.[108][109] On March 3, 2021, an NFT was made to promote the Kings of Leon album When You See Yourself.[110][111][112] Other musicians who have used NFTs include American rapper Lil Pump,[113][114][115] Grimes,[116] visual artist Shepard Fairey in collaboration with record producer Mike Dean,[117] and rapper Eminem.[118]

A paper presented at the 40th International Conference on Information Systems in Munich in 2019 suggested using NFTs as tickets for different types of events.[119] This would enable organizers of the respective events or artists performing there to receive royalties on the resale of each ticket.[120]

Other associated files

- A number of internet memes have been associated with NFTs, which were minted and sold by their creators or by their subjects.[121] Examples include Doge, an image of a Shiba Inu dog,[122] as well as Charlie Bit My Finger,[123] Nyan Cat,[124][125] and Disaster Girl.[126]

- Some virtual worlds, often marketed as metaverses, have incorporated NFTs as a means of trading virtual items and virtual real estate.[127]

- Some pornographic works have been sold as NFTs, though hostility from NFT marketplaces towards pornographic material has presented significant drawbacks for creators.[128][129] By using NFTs people engaged in this area of the entertainment-industry are able to publish their works without third-party platforms being able to delete them.[130]

- The first credited political protest NFT ("Destruction of Nazi Monument Symbolizing Contemporary Lithuania") was a video filmed by Professor Stanislovas Tomas on April 8, 2019, and minted on March 29, 2021. In the video, Tomas uses a sledgehammer to destroy a state-sponsored Lithuanian plaque located on the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences honoring Nazi war criminal Jonas Noreika.[131]

- In 2020, CryptoKitties developer Dapper Labs released the NBA TopShot project, which allowed the purchase of NFTs linked to basketball highlights.[132] The project was built on top of the Flow blockchain.[133]

- In March 2021 an NFT of Twitter founder Jack Dorsey's first-ever tweet sold for $2.9 million. The same NFT was listed for sale in 2022 at $48 million, but only achieved a top bid of $280.[134]

- On December 15, 2022, Donald Trump, former president of the United States, announced a line of NFTs featuring images of himself for $99 each.[135] It was reported that he made between $100,001 and $1 million from the scheme.[136]

Use cases of NFTs in science and medicine

NFTs have been proposed for purposes related to scientific and medical purposes.[137] Suggestions include turning patient data into NFTs,[138] tracking supply chains[139] and minting patents as NFTs.[140]

The monetary aspect of the sale of NFTs has been used by academic institutions to finance research projects.

- The University of California, Berkeley announced in May 2021 its intention to auction NFTs of two patents of inventions for which the creators had received a Nobel Prize: the patents for CRISPR gene editing and cancer immunotherapy. The university would, however, retain ownership of the patents.[141][142] 85% of funds gathered through the sale of the collection were to be used to finance research.[143][144] The collection included handwritten notices and faxes by James Allison and was named The Fourth Pillar. It sold in June 2022 for 22 Ether, about US$54,000 at the time.[145]

- George Church, a US geneticist, announced his intention to sell his DNA via NFTs and use the profits to finance research conducted by Nebula Genomics. In June 2022, 20 NFTs with his likeness were published instead of the originally planned NFTs of his DNA due to the market conditions at the time.[137] Despite mixed reactions, the project is considered to be part of an effort to use the genetic data of 15,000 individuals to support genetic research. By using NFTs the project wants to ensure that the users submitting their genetic data are able to receive direct payment for their contributions.[137][146] Several other companies have been involved in similar and often criticized efforts to use blockchain-based genetic data in order to guarantee users more control over their data and enable them to receive direct financial compensation whenever their data is being sold.[145]

- Molecule Protocol, a project based in Switzerland, is trying to use NFTs to digitize the intellectual copyright of individual scientists and research teams to finance research.[147] The project's whitepaper explains the aim is to represent the copyright of scientific papers as NFTs and enable their trade between researchers and investors on a future marketplace.[148] The project was able to raise US$12 million in seed money in July 2022.[147] A similar approach has been announced by RMDS Lab.[149]

Speculation

NFTs representing digital collectables and artworks are a speculative asset.[150] The NFT buying surge was called an economic bubble by experts, who also compared it to the Dot-com bubble.[151][152] In March 2021 Mike Winkelmann called NFTs an "irrational exuberance bubble".[153] By mid-April 2021, demand subsided, causing prices to fall significantly.[154] Financial theorist William J. Bernstein compared the NFT market to 17th-century tulip mania, saying any speculative bubble requires a technological advance for people to "get excited about", with part of that enthusiasm coming from the extreme predictions being made about the product.[155] For regulatory policymakers, NFTs have exacerbated challenges such as speculation, fraud, and high volatility.[156]

Money laundering

NFTs, as with other blockchain securities and with traditional art sales, can potentially be used for money laundering.[157] NFTs can be used for wash trading by creating several wallets for one individual, generating several fictitious sales and consequently selling the respective NFT to a third party.[158] According to a report by Chainalysis these types of wash trades are becoming popular among money launderers because of the largely anonymous nature of transactions on NFT marketplaces.[159][160][161] Looksrare, created in early 2022, came to be known for the large sums generated through the sale of NFTs in its earliest days, amounting to US$400,000,000 a day. These large sums were generated in large part through wash trading.[161] The Royal United Services Institute said that any risks in relation to money laundering through NFTs could be mitigated through the use of "KYC best practices, strong cyber security measures and a stolen art registry (...) without restricting the growth of this new market".[157]

Auction platforms for NFTs may face regulatory pressure to comply with anti-money laundering legislation. Gou Wenjun, the director of a monitoring centre for the People's Bank of China, said that NFTs could "easily become money-laundering tools". He pointed to unlawful exploitation of cryptographic technologies and said that illicit actors often presented themselves as innovators in financial technology.[162]

A 2022 study from the United States Treasury assessed that there was "some evidence of money laundering risk in the high-value art market", including through "the emerging digital art market, such as the use of non-fungible tokens (NFTs)".[163] The study considered how NFT transactions may be a simpler option for laundering money through art by avoiding the transportation or insurance complications in trading physical art. Several NFT exchanges were labeled as virtual asset service providers that may be subject to Financial Crimes Enforcement Network regulations.[164] In March 2022, two people were charged for the execution of a million-dollar NFT scheme through wire fraud.[165]

The European Commission announced in July 2022 that it was planning to draw up regulations to combat money laundering by 2024.[166][167]

Other uses

- In 2019, Nike patented a system called CryptoKicks that would use NFTs to verify the authenticity of its physical products and would give a virtual version of the shoe to the customer.[168]

- Certain NFT releases have also added exclusivity to the NFT utility, including access to private online clubs.[169][170]

Standards in blockchains

Several blockchains have added support for NFTs since Ethereum created its ERC-721 standard.[171][172]

ERC-721 is an "inheritable" smart contract standard, which means that developers can create contracts by copying from a reference implementation. ERC-721 provides core methods that allow tracking the owner of a unique identifier, as well as a way for the owner to transfer the asset to others.[171] Another standard, ERC-1155, offers "semi-fungibility" whereby a token represents a class of interchangeable assets.[173]

Issues and criticisms

Unenforceability of content ownership

Because the contents of NFTs are publicly accessible, anybody can easily copy a file referenced by an NFT. Furthermore, the ownership of an NFT on the blockchain does not inherently convey legally enforceable intellectual property rights to the file.

It has become well known that an NFT image can be copied or saved from a web browser by using a right click menu to download the referenced image. NFT supporters disparage this duplication of NFT artwork as a "right-clicker mentality". One collector quoted by Vice compared the value of a purchased NFT (in contrast to an unpurchased copy of the underlying asset) to that of a status symbol "to show off that they can afford to pay that much".[14]

The "right-clicker mentality" phrase spread virally after its introduction, particularly among those who were critical of the NFT marketplace and who appropriated the term to flaunt their ability to capture digital art backed by NFT with ease.[14] This criticism was promoted by Australian programmer Geoffrey Huntley who created "The NFT Bay", modeled after The Pirate Bay. The NFT Bay advertised a torrent file purported to contain 19 terabytes of digital art NFT images. Huntley compared his work to an art project from Pauline Pantsdown and hoped the site would help educate users on what NFTs are and are not.[174]

Storage off-chain

NFTs that represent digital art generally do not store the associated artwork file on the blockchain due to the large size of such a file and the limited processing speed of blockchains. Such a token functions like a certificate of ownership, with a web address that points to the piece of art in question; this however makes the art itself vulnerable to link rot.[26]

Environmental concerns

NFT purchases and sales have been enabled by the high energy usage, and consequent greenhouse gas emissions, associated with some kinds of blockchain transactions.[175] Though all forms of Ethereum transactions have had an impact on the environment, the direct impact of these transaction has also depended on the size of the transaction.[176] The proof-of-work protocol required to regulate and verify blockchain transactions on networks (including Ethereum until 2022) consumes a large amount of electricity.[177][178] To estimate the carbon footprint of a given NFT transaction requires a variety of assumptions or estimations about the manner in which that transaction is set up on the blockchain, the economic behavior of blockchain miners (and the energy demands of their mining equipment),[179] and the amount of renewable energy being used on these networks.[180] There are also conceptual questions, such as whether the carbon footprint estimate for an NFT purchase should incorporate some portion of the ongoing energy demand of the underlying network, or just the marginal impact of that particular purchase.[181] An analogy might be the carbon footprint associated with an additional passenger on a given airline flight.[175]

In 2022, Ethereum cut its energy usage by 99.99 percent by switching to proof of stake.[182][183] As the NFT market continues to mature, with a focus on sustainable practices and long-term value, platforms like Klever are leading the way by incorporating energy-efficient technologies. Klever use of the Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS)[184] consensus mechanism significantly reduces the environmental impact of NFT transactions, aligning with the market's shift towards more responsible and sustainable practices.

Other approaches to reducing electricity include the use of off-chain transactions as part of minting an NFT.[175] Some NFT markets have offered the option of buying carbon offsets when making NFT purchases, although the environmental benefits of this have been questioned.[185] In some instances, NFT artists have decided against selling some of their own work to limit carbon emission contributions.[186]

Artist and buyer fees

Sales platforms charge artists and buyers fees for minting, listing, claiming, and secondary sales. Analysis of NFT markets in March 2021, in the immediate aftermath of Beeple's "Everydays: the First 5000 Days" selling for US$69.3 million, found that most NFT artworks were selling for less than US$200, with a third selling for less than US$100.[187] Those selling NFTs below $100 were paying platform fees between 72.5% and 157.5% of that amount. On average the fees make up 100.5% of the price, meaning that such artists were on average paying more money in fees than they were making in sales.[187]

Plagiarism and fraud

There have been cases of artists and creators having their work sold by others as an NFT without permission.[188] After the artist Qing Han died in 2020, her identity was assumed by a fraudster and a number of her works became available for purchase as NFTs.[189] Similarly, a seller posing as Banksy succeeded in selling an NFT supposedly made by the artist for $336,000 in 2021; the seller refunded the money after the case drew media attention.[190] In 2022, it was discovered that as part of their NFT marketing campaign, an NFT company that voice actor Troy Baker announced his partnership with had plagiarized voice lines generated from 15.ai, a free AI text-to-speech project.[191][192][193]

The anonymity associated with NFTs and the ease with which they can be forged make it difficult to pursue legal action against NFT plagiarists.[194]

In February 2023, artist Mason Rothschild was ordered to pay $133,000 in damages to Hermès by a New York court, after a jury sided with the copyright holder, for his 2021 digital depictions of the brand's Birkin handbag.[195]

Some NFT marketplaces responded to cases of plagiarism by creating "takedown teams" to respond to artist complaints. The NFT marketplace OpenSea has rules against plagiarism and deepfakes (non-consensual intimate imagery). Some artists criticized OpenSea's efforts, saying they are slow to respond to takedown requests and that artists are subject to support scams from users who claim to be representatives of the platform.[76] Others argue that there is no market incentive for NFT marketplaces to crack down on plagiarism.[194]

- A process known as "sleepminting" allows a fraudster to mint an NFT in an artist's wallet and transfer it back to their own account without the artist becoming aware.[196] This allowed a white hat hacker to mint a fraudulent NFT that had seemingly originated from the wallet of the artist Beeple.[196]

- Plagiarism concerns led the art website DeviantArt to create an algorithm that compares user art posted on the DeviantArt website against art on popular NFT marketplaces. If the algorithm identifies art that is similar, it notifies and instructs the author how they can contact NFT marketplaces to request that they take down their plagiarized work.[76]

- The BBC reported a case of insider trading when an employee of the NFT marketplace OpenSea bought specific NFTs before they were launched, with prior knowledge those NFTs would be promoted on the company's home page. NFT trading is an unregulated market in which there is no legal recourse for such abuses.[197]

- When Adobe announced they were adding NFT support to their graphics editor Photoshop, the company proposed creating an InterPlanetary File System database as an alternative means of establishing authenticity for digital works.[198]

- The price paid for specific NFTs and the sales volume of a particular NFT author may be artificially inflated by wash trading, which is prevalent due to a lack of government regulation on NFTs.[199][200]

Security

In January 2022, it was reported that some NFTs were being exploited by sellers to unknowingly gather users' IP addresses. The "exploit" works via the off-chain nature of NFT, as the user's computer automatically follows a web address in the NFT to display the content. The server at the address can then log the IP address and, in some cases, dynamically alter the returned content to show the result. OpenSea has a particular vulnerability to this loophole because it allows HTML files to be linked.[201]

Pyramid/Ponzi scheme claims

Critics compare the structure of the NFT market to a pyramid or Ponzi scheme, in which early adopters profit at the expense of those buying in later.[202] In June 2022, Bill Gates stated his belief that NFTs are "100% based on greater fool theory".[203]

"Rug pull" exit scams

A "rug pull" is a scam, similar to an exit scam or a pump and dump scheme, in which the developers of an NFT or other blockchain project hype the value of a project to pump up the price and then suddenly sell all their tokens to lock in massive profits or otherwise abandon the project while removing liquidity, permanently destroying the value of the project.[204]

See also

- Certificate of authenticity

- Decentralized autonomous organization

- Deed

- William Entriken, lead author of ERC-721

- Title (property)

- Web3

Notes

References

- ^ "Definition of NFT". Merriam-Webster. July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Yang, Maya (September 22, 2023). "The vast majority of NFTs are now worthless, new report shows". The Guardian. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Vigliarolo, Brandon (September 21, 2023). "95% of NFTs now totally worthless, say researchers". theregister.com. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ "NFTs Hit $17B In Trading in 2021, Up 21,000%". pymnts.com. March 10, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Genç, Ekin (October 5, 2021). "Investors Spent Millions on 'Evolved Apes' NFTs. Then They Got Scammed". Vice Media. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ Hawkins, John (January 13, 2022). "NFTs, an overblown speculative bubble inflated by pop culture and crypto mania". The Conversation. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Linares, Maria Gracia Santillana. "Cardano NFTs Becomes Third-Largest NFT Protocol By Trading Volume". Forbes. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Vigna, Paul (May 3, 2022). "NFT Sales Are Flatlining". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Kathleen Bridget; Karg, Adam; Ghaderi, Hadi (October 2021). "Prospecting non-fungible tokens in the digital economy: Stakeholders and ecosystem, risk and opportunity". Business Horizons. 65 (5): 657–670. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2021.10.007. S2CID 240241342.

- ^ Mayor, Daniel (April 4, 2022). "NFTs and the Legitimizing Power of Copyright".

- ^ Dean, Sam (March 11, 2021). "$69 million for digital art? The NFT craze, explained". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Kastrenakes, Jacob (March 11, 2021). "Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ^ Mendis, Dinusha (August 24, 2021). "When you buy an NFT, you don't completely own it – here's why". The Conversation. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Gault, Matthew (November 3, 2021). "What the Hell Is 'Right-Clicker Mentality'?". Vice. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "WTF Is an NFT, Anyway? And Should I Care?". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (March 25, 2021). "Your Million-Dollar NFT Can Break Tomorrow If You're Not Careful". The Verge. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Gallagher, Jacob (March 15, 2021). "NFTs Are the Biggest Internet Craze. Do They Work for Sneakers?". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Thaddeus-Johns, Josie (March 11, 2021). "What Are NFTs, Anyway? One Just Sold for $69 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "NFT blockchain drives surge in digital art auctions". BBC. March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ Salmon, Felix (March 12, 2021). "How to exhibit your very own $69 million Beeple". Axios. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Mitchell (March 11, 2021). "NFTs, explained". The Verge. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Majocha, Courtney. "Memes for Sale? Making sense of NFTs". Harvard Law Today. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Ifeanyi, K. C. (January 18, 2022). "The Bored Ape Yacht Club apes into Hollywood". Fast Company. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (March 11, 2022). "Bored Ape Yacht Club creator buys CryptoPunks and Meebits". The Verge. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (May 7, 2021). "Sotheby's Is Selling the First NFT Ever Minted – and Bidding Starts at $100". Artnet News. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Dash, Anil (April 2, 2021). "NFTs Weren't Supposed to End Like This". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Ostroff, Caitlin (May 8, 2021). "The NFT Origin Story, Starring Digital Cats". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Cult of CryptoPunks". TechCrunch. April 8, 2021. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^

- Faife, Corin (January 27, 2017). "Meme Collectors Are Using the Blockchain to Keep Rare Pepes Rare". Vice. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Ostroff, Caitlin (May 8, 2021). "The NFT Origin Story, Starring Digital Cats". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Casey, Michael J.; Vigna, Paul (November 12, 2014). "BitBeat: Bitcoin 2.0 Firm Counterparty Adopts Ethereum's Software". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- "ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard". Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- León, Riley de (October 1, 2021). "Doodles used to create Gary Vaynerchuk NFT collection sell for $1.2 million in Christie's auction". CNBC. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- "Christie's Is Now Accepting Ether in Exchange for Ethereum's Earliest NFTs". Observer. September 21, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- "Christie's Is Now Accepting Ether in Exchange for Ethereum's Earliest NFTs". Observer. September 21, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- Matney, Lucas (April 8, 2021). "The Cult of CryptoPunks". TechCrunch. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Linares, Maria Gracia Santillana. "Crypto Punk Mania: The Top 10 NFT Collections Of 2022". Forbes. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- "EtherRock NFTs are now worth millions, but are they the originals?". Fortune. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Gottsegen, Will (August 17, 2021). "Free Clipart of a Cartoon Rock Is Selling for $300,000 as NFTs". Vice. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini; Nezhadsistani, Nasim; Bodaghi, Omid; Qu, Qiang (February 9, 2022). "Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens; key technologies and challenges". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 2178. arXiv:2304.10490. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2178B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05920-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8828876. PMID 35140251.

- Nadini, Matthieu; Alessandretti, Laura; Di Giacinto, Flavio; Martino, Mauro; Aiello, Luca Maria; Baronchelli, Andrea (October 22, 2021). "Mapping the NFT revolution: market trends, trade networks, and visual features". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 20902. arXiv:2106.00647. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1120902N. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00053-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8536724. PMID 34686678. S2CID 235266255.

- Schroeder, Stan (December 4, 2017). "How to play CryptoKitties, the insanely popular crypto game". Mashable. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Vereš, Igor (April 2019). "Identification of Unusual Transactions in Blockchain Networks". Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, Informatics and Information Technologies.

- ^ Regner, Ferdinand; Schweizer, André; Urbach, Nils (2022), Lacity, Mary C.; Treiblmaier, Horst (eds.), "Utilizing Non-fungible Tokens for an Event Ticketing System", Blockchains and the Token Economy: Theory and Practice, Technology, Work and Globalization, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 315–343, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95108-5_12, ISBN 978-3-030-95108-5, retrieved November 25, 2023

- ^

- Sherwood, Sonja. "40 under 40 - William Entriken". Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Butler, Michael (June 3, 2021). "This local technologist made Philly the birthplace of the leading NFT standard". Technical.ly. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^

- Regner, Ferdinand; Schweizer, André; Urbach, Nils (2022). "Utilizing Non-fungible Tokens for an Event Ticketing System". Blockchains and the Token Economy. Technology, Work and Globalization. Springer International Publishing. pp. 315–343. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95108-5_12. ISBN 978-3-030-95107-8. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Solouki, Mohammadsadegh; Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini (January 1, 2022). "An In-depth Insight at Digital Ownership Through Dynamic NFTs". Procedia Computer Science. 214: 875–882. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.254. ISSN 1877-0509. S2CID 254484607.

- ^

- Zimmer, Ben (April 16, 2021). "'Fungible': The Idea in the Middle of the NFT Sensation". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Ostroff, Caitlin (May 8, 2021). "The NFT Origin Story, Starring Digital Cats". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Arcenegui, Javier; Arjona, Rosario; Baturone, Iluminada (July 31, 2023). "Non-Fungible Tokens Based on ERC-4519 for the Rental of Smart Homes". Sensors. 23 (16): 7101. Bibcode:2023Senso..23.7101A. doi:10.3390/s23167101. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 10459112. PMID 37631638.

- Solouki, Mohammadsadegh; Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini (January 1, 2022). "An In-depth Insight at Digital Ownership Through Dynamic NFTs". Procedia Computer Science. 214: 875–882. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.254. ISSN 1877-0509. S2CID 254484607.

- Ali, Omar; Momin, Mujtaba; Shrestha, Anup; Das, Ronnie; Alhajj, Fadia; Dwivedi, Yogesh K. (February 1, 2023). "A review of the key challenges of non-fungible tokens". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 187: 122248. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122248. ISSN 0040-1625. S2CID 254394090.

- ^

- Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini; Nezhadsistani, Nasim; Bodaghi, Omid; Qu, Qiang (February 9, 2022). "Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens; key technologies and challenges". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 2178. arXiv:2304.10490. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2178B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05920-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8828876. PMID 35140251. S2CID 246700675.

- Solouki, Mohammadsadegh; Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini (January 1, 2022). "An In-depth Insight at Digital Ownership Through Dynamic NFTs". Procedia Computer Science. 214: 875–882. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.254. ISSN 1877-0509. S2CID 254484607.

- Ali, Omar; Momin, Mujtaba; Shrestha, Anup; Das, Ronnie; Alhajj, Fadia; Dwivedi, Yogesh K. (February 1, 2023). "A review of the key challenges of non-fungible tokens". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 187: 122248. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122248. ISSN 0040-1625. S2CID 254394090.

- ^

- Regner, Ferdinand; Schweizer, André; Urbach, Nils (2022). "Utilizing Non-fungible Tokens for an Event Ticketing System". Blockchains and the Token Economy. Technology, Work and Globalization. Springer International Publishing. pp. 315–343. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95108-5_12. ISBN 978-3-030-95107-8. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini; Nezhadsistani, Nasim; Bodaghi, Omid; Qu, Qiang (February 9, 2022). "Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens; key technologies and challenges". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 2178. arXiv:2304.10490. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2178B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05920-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8828876. PMID 35140251.

- Arcenegui, Javier; Arjona, Rosario; Baturone, Iluminada (July 31, 2023). "Non-Fungible Tokens Based on ERC-4519 for the Rental of Smart Homes". Sensors. 23 (16): 7101. Bibcode:2023Senso..23.7101A. doi:10.3390/s23167101. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 10459112. PMID 37631638.

- Solouki, Mohammadsadegh; Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini (January 1, 2022). "An In-depth Insight at Digital Ownership Through Dynamic NFTs". Procedia Computer Science. 214: 875–882. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2022.11.254. ISSN 1877-0509. S2CID 254484607.

- Mohammed, Madine (September 5, 2022). "Blockchain and NFTs for Time-Bound Access and Monetization of Private Data". IEEE Access. 10: 94186–94202. Bibcode:2022IEEEA..1094186M. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3204274. S2CID 252094824.

- Karayaneva, Natalia. "NFTs Work For Digital Art. They Also Work Perfectly For Real Estate". Forbes. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- Alnuaimi, Noura; Almemari, Alanoud; Madine, Mohammad; Salah, Khaled; Breiki, Hamda Al; Jayaraman, Raja (2022). "NFT Certificates and Proof of Delivery for Fine Jewelry and Gemstones". IEEE Access. 10: 101263–101275. Bibcode:2022IEEEA..10j1263A. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3208698. S2CID 252485842.

- ^

- Karadag, Bulut; Akbulut, Akhan; Zaim, Abdul Halim (2022). "A Review on Blockchain Applications in Fintech Ecosystem". 2022 International Conference on Advanced Creative Networks and Intelligent Systems (ICACNIS). pp. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ICACNIS57039.2022.10054910. ISBN 979-8-3503-3444-9. S2CID 257313812. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Chandra, Yanto (November 1, 2022). "Non-fungible token-enabled entrepreneurship: A conceptual framework". Journal of Business Venturing Insights. 18: e00323. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00323. ISSN 2352-6734. S2CID 248958972.

- Ali, Omar; Momin, Mujtaba; Shrestha, Anup; Das, Ronnie; Alhajj, Fadia; Dwivedi, Yogesh K. (February 1, 2023). "A review of the key challenges of non-fungible tokens". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 187: 122248. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122248. ISSN 0040-1625. S2CID 254394090.

- ^ a b

- Zimmer, Ben (April 16, 2021). "'Fungible': The Idea in the Middle of the NFT Sensation". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- Upson, Sandra. "The 10,000 Faces That Launched an NFT Revolution". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ "ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard". Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- Ross, Dian; Cretu, Edmond; Lemieux, Victoria (December 15, 2021). "NFTS: Tulip Mania or Digital Renaissance?". 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE. pp. 2262–2272. doi:10.1109/bigdata52589.2021.9671707. ISBN 978-1-6654-3902-2. S2CID 245956102.

- "Reconsider the word "deed" by fulldecent · Pull Request #2 · fulldecent/EIPs". GitHub. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Urbach, Nils (December 13, 2019). "NFTs in Practice – Non-Fungible Tokens as Core Component of a Blockchain-based Event Ticketing Application" (PDF). Fraunhofer Research Center, Finance and Information Management. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "CryptoKitties Mania Overwhelms Ethereum Network's Processing". Bloomberg.com. December 4, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (February 2, 2022). "How one company took over the NFT trade". The Verge. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Matney, Lucas (July 20, 2021). "NFT market OpenSea hits $1.5 billion valuation". TechCrunch. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- "NFTs are most influential in contemporary art power list". cnbctv18.com. December 1, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- "ArtReview Has Released the 2021 Power 100". Hypebeast. December 1, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- Abrams, Amah-Rose (December 1, 2021). "Non-Fungible Tokens Are Deemed the Most Powerful Entity in the Art World in ArtReview's 2021 Power 100 Ranking". Artnet News. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- "Nonhuman Entity Tops 2021 Edition of ArtReview's Annual Power 100". artreview.com. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- "The Two Miami Art Weeks". Yahoo Finance. December 10, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- Khomami, Nadia (December 1, 2021). "Non-fungible tokens take No 1 spot in influential art world power list". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^

- Brown, Abram (March 11, 2021). "Beeple NFT Sells For $69.3 Million, Becoming Most-Expensive Ever". Forbes. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Reilly, Joel (March 15, 2021). "We talked with Beeple about how NFT mania led to his $69 million art sale". Business Insider. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Block, Fang. "Beeple's NFT Fetches Record $69 Million at Christie's". Barron's. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Reyburn, Scott (March 11, 2021). "JPG File Sells for $69 Million, as 'NFT Mania' Gathers Pace". The New York Times. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "The NFT Market Tripled Last Year, and It's Gaining Even More Momentum in 2021". Morning Brew. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "NFTs Are Shaking Up the Art World – But They Could Change So Much More". Time. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Howcroft, Elizabeth (March 17, 2021). "Explainer: NFTs are hot. So what are they?". Reuters. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Weiss, Ben (February 17, 2023). "Ordinals are pushing Bitcoin beyond $25K. What are they?". Fortune Crypto. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Colicev, Anatoli (2022). "How can non-fungible tokens bring value to brands". International Journal of Research in Marketing. 40: 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2022.07.003. S2CID 251183853. Cf. Daniele, Daniel (May 17, 2021). "NFTs' Nifty Copyright Issues - Intellectual Property - Canada". mondaq. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Edward (2022). "NFTs as Decentralized Intellectual Property". University of Illinois Law Review: 20. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4023736. S2CID 247727602. SSRN 4023736. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Patterson, Dan (March 4, 2021). "Blockchain company buys and burns Banksy artwork to turn it into a digital original". CBS News. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Damiani, Jesse (March 1, 2021). "SuperRare And Verisart Announce '10x10' NFT Auction Series Featuring Neïl Beloufa, Petra Cortright, Shepard Fairey, And More". Forbes. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ "Pak Breaks Record for Most Expensive NFT Sale". HYPEBEAST. December 7, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ Thaddeus-Johns, Josie (March 11, 2021). "What Are NFTs, Anyway? One Just Sold for $69 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Sugiura, Eri (October 13, 2021). "NFTs turn Japan's manga and anime into genuine art". Financial Times. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "Banksy art burned, destroyed and sold as token in 'money-making stunt'". BBC News. March 9, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Iscoe, Adam (May 8, 2021). "Burnt Banksy's Inflammatory N.F.T. Not-Art". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Lu, Fei (January 6, 2022). "Does NFT Art Have A Place in the Museum in 2022?". Jing Culture and Commerce. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ "Why many art collectors are staying away from the NFT gold rush". The Independent. April 30, 2021. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Valeonti, Foteini; Bikakis, Antonis; Terras, Melissa; Speed, Chris; Hudson-Smith, Andrew; Chalkias, Konstantinos (January 2021). "Crypto Collectibles, Museum Funding and OpenGLAM: Challenges, Opportunities and the Potential of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs)". Applied Sciences. 11 (21): 9931. doi:10.3390/app11219931.

- ^ "Italian government plans to halt digital sales of masterpieces from its major museums". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. July 8, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Rodeck, David (May 10, 2022). "Top NFT Marketplaces Of 2022". Forbes Advisor. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Ehrlich, Steven. "NFT Marketplace CEO Explains Why The Industry Is Moving Beyond Ideological Purists". Forbes. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Beer, Tommy. "NBA Top Shot Collectibles Continues Meteoric Rise With Over $50 Million in Sales in a Week". Forbes. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Bumbaca, Chris. "What is NBA Top Shot and why is a LeBron highlight worth $208K? 'This is a real market,' Mark Cuban says". USA Today. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Tepper, Taylor (May 27, 2021). "Binance.US Review 2022". Forbes Advisor. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ "eToro ART". etoro.art. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ "Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale". sothebys.com.

- ^ "Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million". The Verge. March 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Web3's early promise for artists tainted by rampant stolen works and likenesses". TechCrunch. January 27, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "Krista Kim's Mars House is 'first NFT digital house' to be sold over $500,000". World Architecture Community. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ Quiroz-Gutierrez, Marco (March 22, 2021). "NFTs Are Spurring a Digital Land Grab – in Videogame Worlds". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Cristina (October 15, 2021). "Is Heroes & Empires free to play?". Gamepur. Gamurs. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021.

- ^ "CryptoKitties craze slows down transactions on Ethereum". BBC News. December 5, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Tepper, Fitz (March 21, 2018). "CryptoKitties raises $12M from Andreessen Horowitz and Union Square Ventures". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (December 6, 2017). "Meet CryptoKitties, the $100,000 digital beanie babies epitomizing the cryptocurrency mania". CNBC. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ For the future potential of blockchain games with CryptoKitties as an example see Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini; et al. (February 2, 2022). "Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens: key technologies and challenges". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 2178. arXiv:2304.10490. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2178B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05920-6. PMC 8828876. PMID 35140251. S2CID 246700675. Cf. Serada, Alesja; Sihvonen, Tanja; Harviainen, J. Tuomas (February 20, 2020). "CryptoKitties and the New Ludic Economy: How Blockchain Introduces Value, Ownership, and Scarcity in Digital Gaming". Games and Culture. 16 (4): 457–480. doi:10.1177/1555412019898305. S2CID 213245049.

- ^ Entriken, William (June 22, 2018). "Move EIP 721 to Final (#1170) ethereum/EIPs@b015a86". GitHub. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Entriken, William; Shirley, Dieter; Evans, Jacob; Natassia, Sachs (January 24, 2018). "EIP-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard". Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Jiang, Sisi (October 15, 2021). "Good Riddance: Steam Bans Games That Feature Crypto And NFTs". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Ubisoft's NFT Announcement Has Been Intensely Disliked". Kotaku. December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ GameCentral (December 8, 2021). "Ubisoft unlist Quartz NFT announcement video as it gets 16K dislikes". Metro. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ubisoft Developers Confused, Upset Over NFT Plans". Game Rant. December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ubisoft Quartz: Some developers of the company didn't like entering the world of NFTs". Pledge Times. December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ Nightingale, Ed (December 16, 2021). "French trade union criticises Ubisoft Quartz as "a useless, costly, ecologically mortifying tech"". Eurogamer. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ Jeffrey, Cal. "Game Developers Conference report: most developers frown on blockchain games". TechSpot. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Peters, Jay (January 20, 2022). "Many game developers hate NFTs, too". The Verge. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Dana (October 4, 2021). "Dolce & Gabbana Just Set a $6 Million Record for Fashion NFTs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Isabelle (November 17, 2021). "Luxury NFTs could become a $56 billion market by 2030 and could see 'dramatically' increased demand thanks to the metaverse, Morgan Stanley says". Insider. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Josh (July 21, 2022). "Minecraft developers won't allow NFTs on gaming platform". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. p. 32 f. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540.

- ^ Lee, Edward (2022). "NFTs as Decentralized Intellectual Property". University of Illinois Law Review: 36, 39, 43. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4023736. S2CID 247727602. SSRN 4023736. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

Using NFTs, artists now have the option of choosing to require a resale royalty for every resale of their NFTs.

- ^ Heal, Jordan (June 24, 2019). "Deadpool posters can now be bought as NFTs". Coin Rivet. Retrieved May 19, 2021 – via Yahoo!. Cf. Chmielewski, Dawn C. (August 3, 2018). "'Deadpool 2' Jumps on the Digital Collectibles Bandwagon". Deadline. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Ravindran, Manori (March 15, 2021). "NFT Craze Enters Film World: 'Claude Lanzmann' Documentary is First Oscar Nominee to Be Released as Digital Token". Variety. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Bosselman, Haley (March 31, 2021). "'Godzilla vs. Kong' to Have First Major Motion Picture NFT Art Release". Variety. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. p. 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540.

- ^ Finn, John (April 30, 2021). "World's First Movie Score & Soundtrack For Sale As An NFT". ScreenRant. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Diaz, Johnny (November 17, 2017). "Miramax Sues Quentin Tarantino Over Planned 'Pulp Fiction' NFTs". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2021. Cf. Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. p. 33. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540. See also Lee, Edward (2022). "NFTs as Decentralized Intellectual Property". University of Illinois Law Review: 41 f. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4023736. S2CID 247727602. SSRN 4023736. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Bethany Minelle (September 2, 2022). "Muse's Will Of The People becomes first UK number one album with NFT technology". news.sky.com. Sky News. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Eamonn Forde (August 1, 2022). "Sales from the crypto: Muse NFT album to become first new chart-eligible format in seven years". The Guardian. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Stassen, Murray (March 12, 2021). "Music-related NFT sales have topped $25m in the past month". Music Business Worldwide. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Abram. "Largest NFT Sale Ever Came From A Business School Dropout Turned Star DJ". Forbes. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Barcelin, Jason (May 1, 2021). "Las Vegas DJ-producer makes millions selling NFTs". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Hissong, Samantha (March 3, 2021). "Kings of Leon Will Be the First Band to Release an Album as an NFT". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Steele, Anne (March 23, 2021). "Musicians Turn to NFTs to Make Up for Lost Revenue". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Hissong, Samantha (March 9, 2021). "Music NFTs Have Gone Mainstream. Who's In?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "CEO of Sweet Talks NFT Partnership with Rapper Lil Pump". Cheddar. March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Curto, Justin (March 18, 2021). "Musician NFT Projects, Ranked by How Many F's I Can Give". Vulture. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ "Rappers and NFTs – How Hip-Hop Is Cashing in on Non-Fungible Tokens". XXL Mag. March 23, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (March 1, 2021). "Grimes sold $6 million worth of digital art as NFTs". The Verge. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Halperin, Shirley (April 21, 2021). "Mike Dean and Shepard Fairey Team for NFT Offering 'OBEY 4:22'". Variety. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil. "Eminem's First NFT Drop, 'Shady Con,' Includes One-of-a-Kind Slim Shady-Produced Beats". Billboard. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Regner, Ferdinand; Schweizer, André; Urbach, Nils (March 15, 2021). "NFTs in Practice – Non-Fungible Tokens as Core Component of a Blockchain-based Event Ticketing Application". Researchgate. Retrieved January 3, 2023. Cf. "Golden Ticket: How NFTs Can Help Artists Profit From Ticket Resales". MiamiLaw. April 12, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021. See also "NFTs: The future of ticketing?". IQ Mag. May 6, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Gonserkewitz, Phil; Karger, Erik; Jagals, Marvin (2022). "Non-Fungible Tokens: Use Cases of NFTs and Future Research Agenda". Risk Governance & Control: Financial Markets & Institutions. 12 (3): 13. doi:10.22495/rgcv12i3p1. S2CID 252304860.

For tickets to events, there is a secondary market where the seller can call an arbitrary price. There is a risk of purchasing invalid tickets. Regular tickets can also be copied and thus sold multiple times, although only one of them is valid. NFTs can guarantee the uniqueness and authenticity of the tickets

- ^ "NFTs and me: meet the people trying to sell their memes for millions". The Guardian. June 23, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ "Iconic 'Doge' meme NFT breaks record, selling for $4 million". NBC News. June 11, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ "Charlie Bit Me NFT sale: Brothers to pay for university with auction money". BBC News. June 3, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Griffith, Erin (February 22, 2021). "Why an Animated Flying Cat With a Pop-Tart Body Sold for Almost $600,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ Griffith, Erin (February 22, 2021). "Why an Animated Flying Cat With a Pop-Tart Body Sold for Almost $600,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "Zoë Roth sells 'Disaster Girl' meme as NFT for $500,000". BBC News. April 30, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ "Virtual real estate plot sells for close to $1 mln". Reuters. June 18, 2021.

- ^ Dickson, EJ (March 16, 2021). "Porn Creators Are Getting in on the NFT Craze". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Cole, Samantha (March 19, 2021). "'Building the Cockchain:' How NSFW Artists Are Shaping the Future of NFTs". Vice. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540.

- ^ Starr, Michael (April 1, 2021). "Activist turns anti-Nazi act into commodified digital art". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "CryptoKitties developer launches NBA TopShot, a new blockchain-based collectible collab with the NBA". TechCrunch. May 27, 2020. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Daniel (March 11, 2021). "NFTs are both priceless and worthless". Engadget. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ "Auction of Jack Dorsey Tweet NFT Comes in Millions Below Target". Bloomberg News. April 13, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022. (Subscription required.)

- ^ Johnson, Ted (December 15, 2022). "Donald Trump's Major Announcement: Digital Trading Cards Of Himself For "Only $99 Each"". Deadline. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ Washington, Alistair Dawber. "Donald Trump NFTs net former president up to $1m". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Jones, Nicola (June 18, 2021). "How scientists are embracing NFTs". Nature. 594 (7864): 481–482. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..481J. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01642-3. PMID 34145410. S2CID 235481285.

- ^ Kostick-Quenet, Kristin; et al. (February 3, 2022). "How NFTs could transform health information exchange". Science. 375 (6580): 500―502. Bibcode:2022Sci...375..500K. doi:10.1126/science.abm2004. PMC 10111125. PMID 35113709. S2CID 246529093.

- ^ Chiacchio, F.; et al. (April 15, 2022). "Non-Fungible Token Solution for the Track and Trace of Pharmaceutical Supply Chain". Applied Sciences. 12 (8): 4019. doi:10.3390/app12084019. Cf. Gayialis, Sotiris P.; et al. (September 17, 2022). "A Business Process Reference Model for the Development of a Wine Traceability System". Sustainability. 14 (18): 3. doi:10.3390/su141811687.

- ^ Bamakan, Seyed Mojtaba Hosseini; et al. (February 9, 2022). "Patents and intellectual property assets as non-fungible tokens; key technologies and challenges". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 2178. arXiv:2304.10490. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.2178B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05920-6. PMC 8828876. PMID 35140251. S2CID 246700675. Cf. Hasan, Haya R.; et al. (July 19, 2022). "Incorporating Registration, Reputation, and Incentivization Into the NFT Ecosystem". IEEE Access. 10: 76417. Bibcode:2022IEEEA..1076416H. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3192388. S2CID 250710317.

The paper describes the solution's various layers, which include storage, authentication, verification, blockchain, and the application layer. The authors focused on utilizing NFTs to protect intellectual properties. Their framework is theoretical and can be improved upon by adding a programmable logic implementation using smart contracts.

- ^ Whitford, Emma (May 28, 2021). "UC Berkeley Will Auction NFTs for 2 Nobel Prize Patents". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Sestino, Andrea; Guido, Gianluigi; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2022). Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Examining the Impact on Consumers and Marketing Strategies. p. 28. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07203-1. ISBN 978-3-031-07202-4. S2CID 250238540.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (May 27, 2021). "You Can Buy a Piece of a Nobel Prize-Winning Discovery". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Trautman, Lawrence J. (2022). "Virtual Art and Non-Fungible Tokens" (PDF). Hofstra Law Review. 50 (361): 369 f. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3814087. S2CID 234830426.

- ^ a b Jones, Nicola (June 18, 2021). "How scientists are embracing NFTs". Nature. 594 (7864): 482. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..481J. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01642-3. PMID 34145410. S2CID 235481285.

- ^ Tangermann, Victor (April 21, 2022). "A Harvard Scientist is Selling his Genetic Code as an NFT". Neoscope ― Futurism. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Kanetkar, Riddhi (December 5, 2022). "The pandemic was a crisis that fueled interest in novel drug discovery methods like AI. These 14 startups are predicted by investors to be future winners". Businessinsider. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "Molecule Documentation, s.v. "IP-NFT Protocol"". Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "rmdslab.com". Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Howcroft, Elizabeth (August 25, 2021). "NFT sales surge as speculators pile in, sceptics see bubble". Reuters. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Reyburn, Scott (March 30, 2021). "Art's NFT Question: Next Frontier in Trading, or a New Form of Tulip?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Small, Zachary (April 28, 2021). "As Auctioneers and Artists Rush into NFTs, Many Collectors Stay Away". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Cuthbertson, Anthony (March 24, 2021). "NFT MILLIONAIRE BEEPLE SAYS CRYPTO ART IS BUBBLE AND WILL 'ABSOLUTELY GO TO ZERO'". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2022.(subscription required)

- ^ Tarmy, James; Kharif, Olga (April 15, 2021). "These Crypto Bros Want to Be the Guggenheims of NFT Art". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Vanek Smithj, Stacey; Woods, Darian (August 4, 2021). "The Origin of Value: The Greater Fools Theory: The Indicator from Planet Money". NPR. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Bao, Hong; Roubaud, David (May 8, 2022). "Non-Fungible Token: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda". Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 15 (5): 215. doi:10.3390/jrfm15050215. hdl:10419/274737. ISSN 1911-8074.

- ^ a b Owen, Allison; Chase, Isabella (December 2, 2021). NFTs: A New Frontier for Money Laundering? (Report). Royal United Services Institute. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art (PDF) (Report). United States Department of the Treasury. 2022. p. 27. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Quiroz-Gutierrez, Marco (February 4, 2022). "A handful of NFT users are making big money off of a stealth scam. Here's how 'wash trading' works". Fortune. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "Crime and NFTs: Chainalysis Detects Significant Wash Trading and Some NFT Money Laundering In this Emerging Asset Class". Chainalysis. February 2, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Littmann, Saskia (February 5, 2022). "Geldwäscher entdecken den NFT-Markt". Wirtschaftswoche (in German). Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ Coco, Feng (December 2, 2021). "China's market for NFTs, metaverse may drive money laundering". South China Morning Post. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Treasury Releases Study on Illicit Finance in the High-Value Art Market". U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art (PDF) (Report). United States Department of the Treasury. 2022. p. 26. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ "Two Defendants Charged in Non-Fungible Token ("NFT") Fraud And Money Laundering Scheme". March 24, 2022.

- ^ Reiche, Matthias (July 12, 2022). "Umgang mit Bitcoin & Co. Wie die EU den Kryptomarkt reguliert" (in German). Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ Schickler, Jack (September 2, 2022). "Money Laundering via Metaverse, DeFi, NFTs Targeted by EU Lawmakers' Latest Draft". Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ Gallagher, Jacob (March 15, 2021). "NFTs Are the Biggest Internet Craze. Do They Work for Sneakers?". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "I Joined a Penguin NFT Club Because Apparently That's What We Do Now". The New York Times. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- ^ Chayka, Kyle (July 30, 2021). "Why Bored Ape Avatars Are Taking Over Twitter". The New Yorker.

- ^ a b "EIP-721: ERC-721 Non-Fungible Token Standard". Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Volpicelli, Gian (February 24, 2021). "The bitcoin elite are spending millions on collectable memes". Wired UK.

- ^ "EIP-1155: ERC-1155 Multi Token Standard". Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Gault, Matthew (November 18, 2021). "Someone Made a Pirate Bay for NFTs". Vice. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c Calma, Justine (March 15, 2021). "The climate controversy swirling around NFTs". The Verge. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Marro, Samuele; Donno, Luca (January 29, 2022). "Green NFTs: A Study on the Environmental Impact of Cryptoart Technologies". arXiv:2202.00003 [cs.CR].

- ^ Krause, Max; Tolaymat, Thabet (2018). "Quantification of energy and carbon costs for mining cryptocurrencies". Nature Sustainability. 1: 814. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0188-8.

- ^ Gallersdorfer, Ulrich; Klassen, Lena; Stoll, Christian (2020). "Energy Consumption of Cryptocurrencies Beyond Bitcoin". Joule. 4 (9): 1843–1846. Bibcode:2020Joule...4.1843G. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2020.07.013. PMC 7402366. PMID 32838201.

- ^ deVries, Alex (May 16, 2018). "Bitcoin's Growing Energy Problem". Joule. 2 (5): 801–805. Bibcode:2018Joule...2..801D. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.04.016.

- ^ Cuen, Leigh (March 21, 2021). "The debate about cryptocurrency and energy consumption". TechCrunch.

- ^ De-Mattei, Shanti Escalante (April 14, 2021). "Should You Worry About the Environmental Impact of Your NFTs?". Art News. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (April 26, 2023). "Cryptocurrency Ethereum has slashed its energy use by 99.99 per cent". New Scientist.

- ^ Clark, Aaron (December 6, 2022). "Ethereum's Energy Revamp Is No Guarantee of Global Climate Gains". Bloomberg.

- ^ Hu, Qian; Yan, Biwei; Han, Yubing; Yu, Jiguo (January 1, 2021). "An Improved Delegated Proof of Stake Consensus Algorithm". Procedia Computer Science. 2020 International Conference on Identification, Information and Knowledge in the Internet of Things, IIKI2020. 187: 341–346. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2021.04.109. ISSN 1877-0509.

- ^ Di Liscia, Valentina (April 5, 2021). "Does Carbon Offsetting Really Address the NFT Ecological Dilemma?". Hypoallergic. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Howson, Peter (April 2021). "NFTs: why digital art has such a massive carbon footprint". The Conversation. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Kinsella, Eileen (April 29, 2021). "Think Everyone Is Getting Rich Off NFTs? Most Sales Are Actually $200 or Less, According to One Report". Artnet News. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Rhiannon (April 2, 2021). "NFT digital art: Would you pay millions of pounds for art you can't touch?". inews Technology. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Kwan, Jacklin (July 28, 2021). "An artist died. Then thieves made NFTs of her work". Wired. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "Fake Banksy NFT sold through artist's website for £244k". BBC News. August 31, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Demi (January 18, 2022). "Voiceverse NFT admits to taking voice lines from non-commercial service". NME. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ^ Wright, Steve (January 17, 2022). "Troy Baker-backed NFT company admits to using content without permission". Stevivor. Archived from the original on January 17, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Henry, Joseph (January 18, 2022). "Troy Baker's Partner NFT Company Voiceverse Reportedly Steals Voice Lines From 15.ai". Tech Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Beckett, Lois (January 29, 2022). "'Huge mess of theft and fraud:' artists sound alarm as NFT crime proliferates". The Guardian. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ "Hermès wins landmark lawsuit over 'MetaBirkin' NFTs". Financial Times. February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Schneider, Tim (April 21, 2021). "The Gray Market: How a Brazen Hack of That $69 Million Beeple Revealed the True Vulnerability of the NFT Market (and Other Insights)". artnet news. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "OpenSea admits insider trading of NFTs it promoted". BBC News. September 16, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Mitchell (October 26, 2021). "Photoshop's new NFT button could prove you're the real digital artist". The Verge. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Mwanza, Kevin (December 6, 2021). "New Study: NFT Prices Are Manipulated by Few with Wash Trades (Artificial Demand)". Moguldom. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Traders are selling themselves their own NFTs to drive up prices". Engadget. February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Cox, Joseph (January 27, 2022). "This NFT on OpenSea Will Steal Your IP Address". Vice. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Jemima (January 5, 2022). "Matt Damon's crypto ad is more than just cringeworthy". Financial Times. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Bill Gates says crypto and NFTs are '100% based on greater fool theory'". CNBC. June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.