LabLynx Wiki

Contents

| IRT Powerhouse | |

|---|---|

Facade of the powerhouse on Eleventh Avenue | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Steam power plant |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| Address | 855–869 Eleventh Avenue |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°46′19″N 73°59′32″W / 40.77194°N 73.99222°W |

| Construction started | 1902 |

| Completed | 1905 |

| Opened | October 27, 1904 |

| Owner | Consolidated Edison |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | 500 feet (150 m) (smokestack) |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Steel frame |

| Floor count | 5 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Stanford White |

| Developer | Interborough Rapid Transit Company |

| Engineer | John van Vleck, Lewis B. Stillwell, and S. L. F. Deyo |

| Designated | December 5, 2017 |

| Reference no. | 2374 |

The IRT Powerhouse, also known as the Interborough Rapid Transit Company Powerhouse, is a former power station of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), which operated the New York City Subway's first line. The building fills a block bounded by 58th Street, 59th Street, Eleventh Avenue, and Twelfth Avenue in the Hell's Kitchen and Riverside South neighborhoods of Manhattan.

The IRT Powerhouse was designed in the Renaissance Revival style by Stanford White, an architect working with the firm McKim, Mead & White, and was intended to serve as an aboveground focal point for the IRT. The facade is made of granite, brick, and terracotta, incorporating extensive ornamentation. The interiors were designed by engineers John van Vleck, Lewis B. Stillwell, and S. L. F. Deyo. At its peak, the powerhouse could generate more than 100,000 horsepower (75,000 kW).

The land was acquired in late 1901, and the structure was constructed from 1902 to 1905. Several changes were made to the facility throughout the early and mid-20th century, and an annex to the west was completed in 1950. The New York City Board of Transportation took over operation of the powerhouse when it acquired the IRT in 1940. The building continued to supply power to the subway system until 1959, when Consolidated Edison repurposed the building as part of the New York City steam system. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the powerhouse as a city landmark in 2017, after several decades of attempts to grant landmark status to the building.

Site

The IRT Powerhouse is on the border of the Hell's Kitchen and Riverside South neighborhoods on the West Side of Manhattan in New York City. It carries the addresses 855–869 Eleventh Avenue, 601–669 West 58th Street, and 600–648 West 59th Street.[1][2] The building fills the entire block bounded by 59th Street to the north, 58th Street to the south, Eleventh Avenue to the east, and Twelfth Avenue and the Hudson River to the west.[2][3] The block measures about 200 by 800 feet (61 by 244 m)[4] and is just south of Waterline Square.[2] When it opened, the IRT Powerhouse had a frontage of 200 feet (61 m) along Eleventh Avenue and extended 694 feet (212 m) westward, with a temporary brick wall at the western end.[5][6]

Architecture

The IRT Powerhouse is an elaborately detailed Renaissance Revival building, designed by Stanford White, one of the principal architects of the firm McKim, Mead & White.[7] The interiors were designed by the IRT's managing engineers John van Vleck, Lewis B. Stillwell, and S. L. F. Deyo.[1] The machinery and internal layout were designed by IRT engineer John B. McDonald.[8] The structural design is largely attributed to William C. Phelps, who had also been involved in constructing the Manhattan Railway Company's 74th Street Power Station between 1899 and 1901.[9]

The IRT's directors were personally involved in designing the IRT Powerhouse's facade. According to an IRT history, the directors decided on "an ornate style of treatment" similar to that of other civic projects of the time, while also rendering the building "architecturally attractive".[10] The building's magnificence and ornate details reflect the ideas of the City Beautiful movement.[11] The powerhouse provided power for the original subway line of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). It and served as an aboveground focal point for the system, akin to Grand Central Terminal or St Pancras railway station.[12]

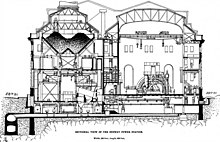

Form

As constructed, the IRT Powerhouse was separated transversely into two sections, both running along the west–east length of the building. The boiler room was on the south, facing 58th Street, while the operating plant with the engines and generators were on the north, facing 59th Street.[13] The section allocated to the boiler room was 83 feet (25 m) wide, while that allocated to the operating plant was 117 feet (36 m) wide.[14] The westernmost section of the block is occupied by an annex completed in 1951.[5]

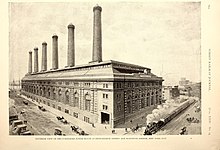

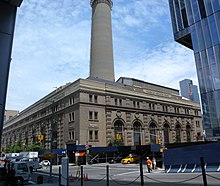

The roof above the IRT Powerhouse is 125 feet (38 m) above its basement.[6] The roof consists of several smaller pitched gables set back from the street. The roof was initially clad with terracotta and contained a large glass clerestory.[15] The building opened with five brick smokestacks, designed to echo the smokestacks on the great steamships at the nearby Hudson River piers.[3][16] These chimneys weighed 1,160 short tons (1,040 long tons; 1,050 t) apiece and rose 162 feet (49 m) above the roofs, or 225 feet (69 m) above the grates in the boiler rooms. The smokestacks were spaced 108 feet (33 m) apart and were lined with thick layers of brick.[17][18] The chimneys measured 21 feet (6.4 m) across at the roofline and 15 feet (4.6 m) across at their tops.[19] A sixth smokestack, similar to the others was added shortly after the powerhouse was completed.[20][16][21] All of these original smokestacks have been demolished. A seventh smokestack, built in 1967, remains on the building's roof.[22][23]

Facade

The facade of the powerhouse is self-supporting and independent of the interior.[24] The base of the powerhouse is clad with Milford granite along its northern, southern, and eastern elevations. The upper stories are clad with brick and terracotta and are divided vertically into bays.[25] On the second and third stories of each bay (except for the outermost bays on each side), there are double-height round-arched window openings topped by decorative archivolts and scrolled keystones. These arched window openings largely contain latticed window frames. In the outermost bays, there are two rectangular windows on either of the second and third stories. There are ornamented horizontal friezes running above the first and third stories and a course above the fourth story. The facade was capped by a cornice, which was later removed.[26][27] The overall design of the facade is based on the Boston Public Library, but with over-scaled design elements.[27]

The most elaborately designed section of the building's facade is the eastern elevation facing Eleventh Avenue, which consists of eight bays. The six center bays project slightly and are flanked by brick and terracotta pilasters. Within these six bays, the tops of the arched openings contain transom panels made of glass. There are palmettes placed at regular intervals along the pilasters.[5] The pilasters correspond exactly to the original chimneys.[19] The northernmost bay, the furthest right along the Eleventh Avenue facade, contains the original main entrance, a rectangular doorway with a classically designed frame.[5][28][29] The fourth-story attic contains pairs of rectangular windows in each bay, surrounded by ornamented window frames.[26][27] A parapet, containing a tablet with the words interborough rapid transit company, runs above the center of the attic. Between the facade and the sidewalk is a planting bed surrounded by an iron railing; the space originally contained a sunken basement court.[26]

The southern elevation on 58th Street and the northern elevation on 59th Street are both nineteen bays wide and differ only slightly from each other in design. The 58th Street facade has basement openings, and the tops of the arched openings contain transom panels made of buff brick. On the 59th Street facade, there are no basement openings, and the arched openings are topped by transom panels with glazed glass. On both facades, each bay is separated by pairs of rusticated brick pilasters, which contain simple bands placed at regular intervals. The fourth-story attic contains triplets of rectangular windows in each bay, surrounded by ornamented window frames, except in the outermost bays, where the windows are paired.[26][27] There are portals on the easternmost bay of both facades, which were originally used by New York Central Railroad freight trains running along Eleventh Avenue; the rail line was later relocated into the West Side Line.[30] Several openings at the base contain roll-down metal gates.[22]

Structural features

The building is supported by a skeletal steel superstructure that weighs about 12,000 short tons (11,000 long tons; 11,000 t).[6] The floors and coal bunkers generally consist of I-beams, as well as plate girders similar to those used on plate girder bridges. The strength of the steelwork necessitated that the building use girders that would normally be used on bridges.[31][17][32] The American Bridge Company manufactured the steel used in the superstructure.[33] The floor girders are 3 inches (76 mm) below the floor surface, and connecting beams are placed 1.5 to 2 inches (38 to 51 mm) beneath the girders. The floor beams rest on "seats" that are riveted to the webs of the girders.[31] The column girders vary in dimension based on the expected load for each column. The columns that support the cranes used in the operating house are supported by cantilevers.[31]

The floors themselves were made of concrete arches, reinforced with expanded metals, with the floor slabs being a minimum of 24 inches (610 mm) thick.[34][35] The floor construction was to withstand test loads of 200 pounds per square foot (980 kg/m2) on all flat portions of the roof, 500 pounds per square foot (2,400 kg/m2) in the engine house, and 300 pounds per square foot (1,500 kg/m2) in the boiler house.[17][34] In the engine house, a secondary floor surface of slate slabs on brick partitions is placed atop the concrete arches. The engine room's main operating floor is on a mezzanine 8 feet (2.4 m) above the boiler house's floor.[34] The roof over the operating house is supported by the crane-supporting columns, while the roof over the boiler room is supported by its own set of columns.[31] The original chimneys were supported by platforms of 24-inch (610 mm) I-beams and a system of plate girders 8 feet (240 cm) deep.[36]

The foundation was constructed using various methods because of the uneven depth of the underlying bedrock, which ranged from about 12 to 35 feet (3.7 to 10.7 m). Cast-iron bases were used to distribute the weight carried by the superstructure columns. Where the bedrock was near the bottoms of the cast-iron bases, a pad of concrete 12 inches (300 mm) thick was poured under the bases. Some of the cast-iron bases rest on concrete foundation piers topped by granite.[6][34] Massive granite bases were also poured into the foundation underneath where each of the twelve engines would be placed.[6][37] The foundation also supports the 397 columns in the superstructure.[6]

Equipment and operations

The IRT Powerhouse was similar in layout to larger power plants.[31][38] The boiler room and the engine and generating room were separated by a brick partition wall.[12][31] Galleries along the north wall of the generating room supported electrical switches and control board, and galleries along the south wall supported the auxiliary steam piping. The main northern gallery also housed equipment for a repair and machine shop.[38] The walls of the boiler room were wainscoted on the lower portion and exposed brick on the upper portion.[31][29] In case of a steam pipe failure in the boiler room, the brick wall would stop the steam from spreading to the generating room.[31][17] Several traveling cranes were also installed throughout the powerhouse.[39][40] When built, the IRT Powerhouse was intended to be the largest generating station on earth.[41]

Boilers

John van Vleck designed the boiler plant of the power house according to a unit plan that divided the plant into six independent functional sections, allowing for high operational flexibility.[42] Each unit contained two rows of six boilers, feeding two steam engines in the generating room. For each unit there were also two condensers, two boiler-feed pumps, two smoke-flue systems with economizers, and two complements of auxiliary apparatus. The twelve boilers were symmetrically arranged around one of the six chimneys.[43] Five of the boiler/engine units were identical; the sixth had a steam turbine plant, installed to power the generator for lighting the subway tunnels.[44] City mains provided the boiler feedwater.[45] The arrangement of the boilers on a single level, and placement of the economizers above the boilers, saved space. The layout permitted a higher, well-lit boiler room, which helped reduce temperature extremes and the risks caused by escaping steam.[17][46] The boiler room ceiling was 35 feet (11 m) high, providing space for ventilation.[47][48]

The powerhouse used 1,000 short tons (890 long tons; 910 t) of coal each day, generating 132,000 horsepower (98,000 kW).[3] Coal was received from a 700-foot-long (210 m) pier on Twelfth Avenue and brought via conveyor belt to the southwest corner of the basement.[49] Coal was stored in one of seven coal bunkers above the boilers, with each bunker being separated by a chimney.[50][a] A set of vertical conveyors, each operating faster than the next, would lift the coal to the bunkers, distributing the coal evenly among each bunker.[54] From the bunkers, the coal could be delivered via a conveyor system to any of the boilers.[51] This allowed multiple grades of coal to be used at different times of the day; for instance, high-grade coal could be distributed to all boilers during peak hours and low-grade coal could be used at other times.[55] After the coal was used in the boilers, the ashes dropped into hoppers beneath the boilers. Locomotives pulled the ash hoppers back beneath Twelfth Avenue to conveyors, which sorted the ashes either to the pier for unloading into barges, or to bunkers where the ashes could be stored before being unloaded later.[56]

Engines

The steam from each group of six boilers fed a steam main. From there, steam could go to the basement to feed the high-pressure cylinders of the engine, or it could enter a manifold, a system of 12-inch pipes connecting the steam mains of all the boiler groups. When the valves to the manifold were shut, each boiler/engine group could be operated independently, and when the valves were open, the 12-inch pipes distributed steam from all the boilers evenly to the engines in the generating room.[57]

The engines themselves were 12,000-horsepower (8,900 kW) reciprocating engines, each pair of which consisted of a high pressure and a low pressure cylinder.[58] Inside the generating room, two barometric jet condensers served each steam engine.[59][60] The condensing water was taken from the Hudson River and filtered, then used to condense the steam from the boilers. The condensing water was discharged into the river after use because the design of jet condensers prevented the steam from being recycled as boiler feedwater.[61] Each of the twelve condensers could handle 10 million U.S. gallons (37,854,000 L; 8,327,000 imp gal) per day.[59]

Generators

The generators were directly fed by the steam engines. As built, there were nine alternating current generators of the flywheel type, each of which had a capacity of 5,000 kilowatts (6,700 hp), making 75 rotations per minute.[62] Stillwell and the electrical engineers chose the 5,000 kW generator because it was large but could still be directly connected to the engine shaft using only two bearings.[63] Larger units required more bearings and were more vulnerable to breakdown, while smaller units could not adjust to sudden load changes necessitated by changes in service during peak hours.[63] The generators produced 3-phase, 25-cycle, 11,000 volt alternating current.[40][64] Current traveled from the generators through the switchboards for distribution to any of eight substations throughout Manhattan and the Bronx. The high tension switches were on the main gallery along the northern wall of the operating plant, and due to their size, were operated in oil so that the circuit could be more easily broken.[17][63] The substations converted the alternating current to 600 volts of direct current,[65] thereby feeding the third rail system that powered the trains.[40][66]

Four 2,000-horsepower (1,500 kW) turbo generators were installed in between the row of alternating current generators; three were in service when the plant was completed. Each turbo generator was fed by a 1,250-kilowatt (1,680 hp) alternator. These produced the light for the subway stations, and alongside the AC generators, could produce 100,000 horsepower (75,000 kW).[67] In addition, there were five exciter units, each of which were 250-kilowatt (340 hp) direct current generators providing 250-volt exciting current for the revolving fields. Three were driven by direct-connection to induction motors, the others by 400-horsepower marine-type steam engines.[68]

History

Planning for the city's first subway line dates to the Rapid Transit Act, authorized by the New York State Legislature in 1894.[69] The subway plans were drawn up by a team of engineers led by William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Rapid Transit Commission.[70] A plan was formally adopted in 1897.[71] The Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company (RTSCC), organized by John B. McDonald and funded by August Belmont Jr., signed Contract 1 with the Rapid Transit Commission in February 1900,[72] in which it would construct the subway and maintain a 50-year operating lease from the opening of the line. Belmont incorporated the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in April 1902 to operate the subway.[73]

Planning and construction

The RTSCC, pursuant to its contract with the city, was required to construct and operate a power house for the subway.[74] The power house was to be powered by steam. It needed easy access to transportation lines for coal delivery, as well as a nearby supply of water for boilers and steam condensing, which made a riverside location optimal. Additionally, the power plant was supposed to be near the center of its distribution area.[75] However, few suitable large sites were available. Three such sites along the East River at 38th, 74th, and 96th Streets were already occupied by power plants.[41][75][b] Parsons wanted a site near Midtown Manhattan, nearer the subway's distribution center, and rejected McDonald's suggestions for sites in Lower Manhattan and Long Island City,[75] as well as another suggestion to build smaller powerhouses underground.[77] In mid-September 1901, the RTSCC signed $1.5 million worth of contracts with Allis-Chalmers, for the engines, and Babcock & Wilcox, for the boilers.[41][78] Two weeks later, McDonald decided to purchase a site between 58th Street, Eleventh Avenue, 59th Street, and Twelfth Avenue for $900,000.[4][79][80]

After buying the land for the powerhouse, Belmont, Deyo, McDonald, and van Vleck went to Europe for one month to research and observe railways and power infrastructure there.[81] Subsequently, Stanford White was employed as the powerhouse's architect.[82][81][27][c] White had drawn up plans for the plant's elevations by February 1902.[81] An early plan, likely by an RTSCC engineer, called for an imposing Romanesque design; the only things it had in common with White's plan were the roof and clerestory.[84] The powerhouse was originally supposed to be made entirely of concrete, but the IRT decided to use brick in March 1902 after bricklayers threatened to strike.[85][86] The plant was also initially intended to be 586 feet (179 m) long, but the IRT's signing of Contract 2 that year necessitated that the powerhouse be lengthened to 694 feet.[81][87] Plans were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings in May 1902, with Deyo as the architect of record.[88][89]

Work proceeded quickly despite several strikes during the course of construction.[81] By the end of 1903, the subway was nearly completed, but the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners said that the labor strikes were holding up the system's opening.[90][91] Because of the delays, the IRT initially contemplated drawing power from the Metropolitan Street Railway's 96th Street powerhouse.[92] When the subcontractors installing the 59th Street plant's electrical and mechanical equipment hired nonunion workers, the labor unions threatened another strike in January 1904,[93][94] which was averted through negotiations.[95][96] The Real Estate Record and Guide reported in April 1904 that, despite a bricklayers' strike, over four hundred workers were employed in constructing the powerhouse, and most of the building had been completed except for the western end.[97] The same journal two months later described the project as "the largest [...] in the city actually under construction".[98][99]

Subway powerhouse

The IRT's 59th Street powerhouse opened on October 27, 1904, along with the first subway line.[98] The completed powerhouse was one of White's last designs, as he was murdered in 1906.[100] The westernmost of the six boiler/engine combinations was not operational at the time of opening, but was activated by late 1904[101] or 1905.[102] The remainder of the block, west of the powerhouse, was underused and contained a storehouse that operated separately.[102] Soon after the powerhouse opened, the IRT set up a laboratory for coal analysis at the unloading dock. Coal was sampled as it left the barge and evaluated according to company specifications. The IRT granted suppliers a bonus for coal of especially good quality, or penalized them for coal of particularly poor quality. The coal laboratory ensured that the plant furnaces received coal most suited to plant conditions, increasing plant efficiency.[101]

The IRT was growing quickly during the first decades of the 20th century and, by 1907, the plant's capacity needed to be increased. Accordingly, additional stokers were installed to increase each boiler's capacity by fifty percent, and eighteen boilers received additional equipment.[103] Further work was done in preparation for a wide-ranging expansion of the IRT system under the Dual Contracts,[102] which were signed in 1913.[104] Between 1909 and 1910, the IRT installed five 7,500-kilowatt (10,100 hp) vertical turbo-generators made by General Electric, as well as surface condensers for each turbine; this added 15,000 kilowatts (20,000 hp) of generating capacity without having to heat the steam further.[105] The IRT gradually replaced stokers at the powerhouse between 1913 and 1917, making the boilers even more efficient. In 1917, the company installed three 35,000-kilowatt (47,000 hp) horizontal General Electric turbo-generators, and added superheaters to 30 boilers. Additionally, a central control service was activated in 1915 at the 59th Street plant; it managed operations at the 59th and 74th Street power stations, as well as several substations on the IRT network.[106] Following a power failure on the IRT subway in 1917 caused by a lack of coal at the 59th Street plant, the New York Public Service Commission required that the IRT maintain a reserve of coal at the 59th and 74th Street plants.[107][108] After the IRT added four boilers with underfeed stokers to the 59th Street plant in 1924, no major upgrades were carried out for the following sixteen years.[106]

The New York City Board of Transportation (BOT) acquired the IRT in 1940, combining it with the city's two other major subway systems, the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation and the Independent Subway System.[109][110] The IRT's 59th Street power station came under the purview of the BOT.[3] By then, the obsolete boilers at the 59th Street plant were causing trains to run at slower speeds due to decreased output.[111] The board decided to enlarge the plant westward to Twelfth Avenue in October 1946.[112]: 18 A $655,000 construction contract was granted to the Harris Structural Steel Company in January 1948.[113] The annex, completed in 1950,[114] expanded the capacity of the plant by 62,500 kilowatts (83,800 hp), with a single, more efficient boiler that required one-third the amount of coal as the old boilers.[112]: 18 [115] In addition, existing switchgear at the plant was replaced.[112]: 18–19 When one of the new circuits was tested at the powerhouse in 1951, it temporarily cut off service to the subway system.[116] The New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) took over operation of the 59th Street plant from the BOT in 1951.[117]

Sale

Despite the expansion, by the mid-1950s, the old equipment was regularly creating large amounts of pollution. Some of the equipment had never been replaced since the building opened, with a 1954 report describing the plant as "an engineering museum piece".[106][117] The NYCTA estimated that upgrades to its three transit powerhouses, including the 59th Street plant, would cost $200 million.[117][118] There were calls for the NYCTA to sell off the plants.[119][120] Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. proposed in November 1956 that Consolidated Edison, also known as Con Ed, make an offer to buy the three plants, although the offer met resistance from the Transport Workers Union of America.[121] The NYCTA urged Wagner to reject the $90 million offer in February 1957, citing that, among other things, the low sale price might force the NYCTA to raise the transit system's fare.[122]

Another recommendation was made to Wagner in April 1958, in which Con Ed would buy the plants for $123 million,[123] and the NYCTA dropped its opposition upon receiving assurances that the fare would be preserved.[124] Con Ed made another offer in February 1959 in which it would pay about $126 million for the plants;[125] the deal was approved by the New York City Board of Estimate the next month.[126] An unnamed group of investors also expressed interest in buying the plants.[127] In May 1959, Con Ed bought the three plants at auction, being the only bidder at that auction.[128] This enabled the NYCTA to purchase additional subway cars with the $9.26 million that would have been used to maintain the plants.[129]

Later years

Soon after buying the transit power plants, Con Ed launched a modernization program for them.[130] The 59th Street plant was soon completely overhauled, becoming a plant for the New York City steam system.[131] Barges delivered oil to the nearby Pier 98 by barge; the oil was used to power the former IRT Powerhouse.[132] In 1960, Con Ed shut down the old low-pressure boilers and installed modern high-pressure boilers. Interconnections were established between the IRT Powerhouse and other transit and Con Ed plants. The labor force was reduced from 1,200 to less than 700, and topping turbines were installed. In 1962, more high-pressure units were activated to replace the low-pressure boilers.[133] This was followed in 1966 by the installation of two boilers and a turbo-generator, as well as the replacement of the western four chimneys with a single 500-foot (150 m) tall smokestack.[133][134] By 1968, the 59th Street plant was exclusively using oil and gas for fuel consumption.[133][135]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) first considered making the IRT Powerhouse a city landmark in 1979. Historian John Tauranac was one of two people to speak in favor of designation, but Con Ed opposed designation of the building, except for the facade's Eleventh Avenue elevation.[136] Walker O. Cain, an architect speaking on behalf of Con Ed, testified that it was unclear whether Stanford White's firm was involved with the construction of the other facades.[3] The LPC held another landmark hearing in 1990, in which several preservation groups and Manhattan Community Board 4 supported designation. Con Ed again objected, stating that the building had been heavily modified, and the LPC declined to designate the building.[3][136][137]

The issue of preservation reemerged in mid-2007 when urban planners Jimmy Finn and Paul Kelterborn founded the Hudson River Powerhouse Group to advocate for landmark status for the IRT Powerhouse.[138] This led the LPC to again reconsider the IRT Powerhouse as a city landmark in 2009.[138][139] The LPC received hundreds of comments or written designations in support of the landmark designation, but declined to grant the structure landmark status yet again, because of opposition from Con Ed.[140] The powerhouse's last original powerhouse was removed that year, prompting concern from preservationists.[11][141] The issue was revived in late 2015, the LPC prioritized the powerhouse for designation as a city landmark.[137][142] This was part of a review of landmark listings that had been calendared by the LPC for several decades, but never approved as city landmarks.[143][144] During public hearings, Con Ed representatives were again the only opponents to landmark designation.[140][145] Accordingly, the LPC tabled the designation while it worked with Con Ed to determine how the building could be preserved while remaining in operation.[146][147] The IRT Powerhouse was designated a city landmark on December 5, 2017.[148] The next month, the LPC approved a restoration plan for the old powerhouse.[149]

Although the IRT Powerhouse no longer produced power, it was part of a network that served 1,500 buildings in Manhattan; the 59th Street steam plant provided about 12 percent of the network's steam capacity as of 2022.[150] Oil deliveries to Pier 58 had declined over the years, and the 59th Street steam plant relied increasingly on a natural-gas pipeline.[132][150] By 2022, the steam network received 3 percent of its power from oil and 97 percent from natural gas.[150]

Reception

Upon the subway's opening, one engineer said that the design was reminiscent of a public library or art museum.[151][152] Critical praise continued through later years. In the 1990s, one writer for The New York Times characterized the IRT Powerhouse as a "thoroughly classical colossus of a building".[21] Clifton Hood, author of a 2004 book about the history of the New York City Subway, described it as "a classical temple that paid homage to modern industry".[153] Several artists, historians, and architects also praised the building in letters to the LPC. These included architect Robert A. M. Stern, art history professor Barry Bergdoll, historic preservation professor Andrew Dolkart, and artist Chuck Close.[154]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 59th to 110th Streets

References

Notes

- ^ The bunkers were variously quoted to have had a capacity of 16,000 tons;[51] 18,000 tons;[52] or 25,000 tons.[53]

- ^ The plants at 38th and 96th Street were demolished. The 74th Street plant, serving the Manhattan Railway Company, is still extant.[76]

- ^ The IRT claimed that he "volunteered his services".[39][76][27] However, records from his company show he was paid $3,000 for the commission to design the building,[27] and that he had been hired by IRT director Charles T. Barney.[76][83]

Citations

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 4.

- ^ a b c "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Christopher (November 17, 1991). "Streetscapes: The IRT Generating Plant on 59th Street; The Power of Design Vs. Con Ed Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Engineering Record 1904, p. 98.

- ^ Framberger 1978, p. 15; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 4; Lowe 1992, p. 194; Roth 1983, p. 313.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 313.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 309.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 74; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 18; Roth 1983, p. 314.

- ^ a b Baldock, Melissa (March 19, 2009). "IRT Powerhouse: Hoping Third Time's A Charm for Landmarking". Municipal Arts Society of New York. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Framberger 1978, p. 15.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 501; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Framberger 1978, p. 15; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 16.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 501; Framberger 1978, p. 17; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f "New Power Plant of Interborough Rapid Transit Company". The New York Times. October 30, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, pp. 508–509; Engineering Record 1904, p. 99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Roth 1983, p. 314.

- ^ Framberger 1978, p. 17.

- ^ a b Glueck, Grace (April 18, 1997). "Appreciating the Palaces of a Sumptuous Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 10.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (May 11, 2009). "After 2 Years, a Meeting on Village Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 503; Framberger 1978, p. 15; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 72; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Framberger 1978, p. 16; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, pp. 74–75; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 8–9; Roth 1983, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Framberger 1978, p. 16.

- ^ Framberger 1978, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 75.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Engineering Record 1904, p. 98; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h American Electrician 1904, p. 501.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 72.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603.

- ^ a b c d American Electrician 1904, p. 502.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 69.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 502; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Engineering Record 1904, p. 98; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 74.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, pp. 603–604.

- ^ a b Kimmelman 1978, p. 310.

- ^ a b Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 608.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 14.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 501; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Engineering Record 1904, p. 99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 67; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310; Roth 1983, p. 313.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 501; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Engineering Record 1904, p. 99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 67; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 69; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 510; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Kimmelman 1978, p. 311.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 69; Kimmelman 1978, p. 311; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 606.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 81.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 604; Engineering Record 1904, p. 98; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 76; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 16.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 501; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 72; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310; Roth 1983, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b American Electrician 1904, p. 506.

- ^ Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 604.

- ^ Engineering Record 1904, pp. 98–99.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 503; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, pp. 604–605; Engineering Record 1904, pp. 98–99; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 16.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 503; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 603; Engineering Record 1904, pp. 98–99; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 503; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 605; Engineering Record 1904, pp. 98–99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 77; Kimmelman 1978, p. 310.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 509; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 606; Kimmelman 1978, p. 312.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 312.

- ^ a b Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 607.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 313.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 510; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 607; Engineering Record 1904, p. 99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 72; Kimmelman 1978, p. 313; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 16.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 511; Engineering Record 1904, p. 100; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, pp. 84–85; Kimmelman 1978, p. 314.

- ^ a b c Kimmelman 1978, p. 314.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 330.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, pp. 330, 332.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 341.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 511; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 607; Engineering Record 1904, p. 99; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 86.

- ^ American Electrician 1904, p. 511; Electrical World and Engineer 1904, p. 607; Engineering Record 1904, p. 100; Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, p. 86.

- ^ Walker 1918, pp. 139–140.

- ^ "Interborough Rapid Transit System, Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Walker 1918, p. 148.

- ^ Report of the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners for the City of New York For The Year Ending December 31, 1904 Accompanied By Reports of the Chief Engineer and of the Auditor. Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners. 1905. pp. 229–236.

- ^ Walker 1918, p. 182.

- ^ Walker 1918, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Kimmelman 1978, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 28.

- ^ "Sites for Power Houses; Contractor McDonald's Application to Use City Property Refused". The New York Times. June 6, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Tunnel Contracts Awarded; Rapid Transit Company Makes a Number for Engines and Bailers Aggregating $1,500,000". The New York Times. September 12, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Power House Site for Rapid Transit; Great Purchase of the Subway Construction Company". The New York Times. September 27, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Gossip of the Week". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 68, no. 1750. September 28, 1901. p. 373. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 15.

- ^ Lowe 1992, p. 194.

- ^ Lowe 1992, pp. 194–196.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Tunnel Labor Dispute Ended; Bricklayers and Masons' International Union Reaches an Agreement With the Contractors". The New York Times. March 9, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Scott 1978, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, pp. 67, 69.

- ^ "The Building Department: List of Plans Filed for New Structures and Alterations". The New York Times. May 10, 1902. p. 14. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Projected Buildings". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 69, no. 1782. May 10, 1902. p. 876. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Walker 1918, p. 186.

- ^ "First of Subway Tests; West Side Experimental Trains to Be Run by Jan. 1". The New York Times. November 14, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Metropolitan May Supply Power for the Subway.; Negotiations in Progress Because of Delays Due to the Interborough's Labor Trouble". The New York Times. September 27, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Scott 1978, p. 267.

- ^ "Subway Work May Be Delayed by Strike; Tile Layers Go Out and 3,000 Other Employees May Follow". The New York Times. January 14, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "No Subway Strike: Differences Settled at a Conference—Statement by Mr. McDonald". New-York Tribune. January 16, 1904. p. 6. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Against Subway Strike; Union Delegates After Stormy Debate Decide for Peace. Labor Bodies, Now in the Employers' Agreement, Carry the Day in Spite of the More Radical of the Leaders". The New York Times. February 1, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "Of Interest to the Building Trades". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 73, no. 1882. April 9, 1904. p. 793. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 16.

- ^ "Change in the Money Situation". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 73, no. 1891. June 11, 1904. p. 1372. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 22.

- ^ a b Kimmelman 1978, p. 315.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 17.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, pp. 315–316.

- ^ "Money Set Aside for New Subways; Board of Estimate Approves City Contracts to be Signed To-day with Interboro and B.R.T." (PDF). The New York Times. March 19, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Interborough Rapid Transit Company 1904, pp. 86–87; Kimmelman 1978, p. 316; Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Kimmelman 1978, p. 316.

- ^ "To Avert Subway Tieups.; Big Reserve Supply of Coal Will Be Kept in Power Houses". The New York Times. September 5, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "P.S.C. Orders a New I.R.T. Coal Reserve". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 4, 1917. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Celebrating 100 Years of the BMT". mta.info. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Sparberg, A.J. (2014). From a Nickel to a Token: The Journey from Board of Transportation to MTA. Fordham University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8232-6192-5. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Chill in IRT Subway Trains Due To Obsolete Boilers, Delaney Says; Plants in Operation 8 Years Longer Than Code Allows, Estimate Board Hears". The New York Times. October 26, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Report for the three and one-half years ending June 30, 1949. New York City Board of Transportation. 1949. hdl:2027/mdp.39015023094926.

- ^ "Low Steel Work Bid on IRT Plant $654,955". The New York Times. January 17, 1948. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Huge New Turbine to Power Subway; West Side Plant Resembling a Tall Mechanized Armory Will Soon Go Into Action". The New York Times. September 9, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "New Transit Plant Rising in 12th Ave". The New York Times. June 26, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Power Cut Halts Subways an Hour As $13,000,000, Unit Gets a Test". The New York Times. November 29, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 23.

- ^ "Power Unit Smoke Is Here to Stay; Transit Authority Facility on 59th St. Needs New Boilers". The New York Times. September 18, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Power Plant Sale Tied to Pollution". The New York Times. November 28, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Queens Chamber Urges City Sell Power Plants to Con Edison Company". Greenpoint Weekly Star. August 15, 1957. p. 3. Retrieved January 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Levey, Stanley (January 27, 1957). "Con Edison Offers to Buy City Plants; Submits Price on 3 Transit Powerhouses". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Levey, Stanley (February 22, 1957). "Transit Unit Bars Bid of 90 Million on Power Plants; Asks Mayor to Reject Offer by Con Edison, Says It Will Bring 72-million Loss". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (April 9, 1958). "Preusse Bids City Sell Con Edison 3 Power Plants; Committee Backs New Offer of 123 Million to Transfer Facilities for Subways". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Levey, Stanley (May 7, 1958). "Authority Scores Power Plant Bid; Fears a Fare Rise; Board Does Not Fight Sale to Con Edison, but Offers Terms for Better Deal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Levey, Stanley (February 5, 1959). "Con Edison Raises Its Offer to City for Power Plants; $125,690,000 Payment and New Terms Proposed for Three Transit Units". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Crowell, Paul (March 13, 1959). "City Votes Deal on Power Plants With Con Edison; but Contract Is Changed to Permit New Bids When Final Auction Is Held". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Power Plant Bid May Be Improved; Group of Investors Said to Plan Better Deal for City Than Con Edison". The New York Times. March 11, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Katz, Ralph (May 20, 1959). "Con Edison Buys Plants Supplying Subways' Power; Company's 125 Million Bid Is Only One Offered for Transit Board Sites". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "Transit Savings to Buy New Cars; $9,256,300 Not Needed to Improve Power Plants Is Shifted in Budget". The New York Times. July 16, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Bennett, Charles G. (July 26, 1959). "Con Ed Outlines Anti-smoke Plan; Hopes to Cut Pollution at 3 Plants It Will Acquire From City Saturday". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Kimmelman 1978, p. 317.

- ^ a b McGeehan, Patrick; Barnard, Anne (August 23, 2022). "Con Ed Dumps Hot, Dirty Water From River Park Pier, Records Show". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kimmelman 1978, p. 328.

- ^ "Con Ed Planning New Smokestacks For 2 City Plants". The New York Times. May 14, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 24.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 27.

- ^ a b "LPC Ponders Powerhouse to the People". amNewYork. November 19, 2015. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Nelson, Libby (July 9, 2009). "A Push to Make a Con Ed Steam Plant a Landmark". City Room. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Pillifant, Reid (April 13, 2009). "Smokestack Attack! Move to Preserve Hudson River Powerhouse". Observer. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Buckley, Cara (January 15, 2010). "A Recession, but Threats Persist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 11, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Hogan, Gwynne (October 23, 2015). "'Do or Die' Moment for Preservation of West Side IRT Powerhouse: Activists". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ "IRT Powerhouse, Still in Use, Among Those Headed for Preservation". amNewYork. March 10, 2016. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Chaban, Matt A. V. (February 23, 2016). "Landmark Status Is Urged for 30 New York City Properties". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Bindelglass, Evan (November 6, 2015). "Public Strongly Supports Landmarking The Former IRT Powerhouse On The Far West Side". New York Yimby. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Chaban, Matt A. V. (December 14, 2016). "10 New York Sites Get Landmark Status as Panel Clears Backlog". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Rajamani, Maya (December 15, 2016). "IRT Powerhouse May Still Become First-Ever Power Plant Landmark, City Says". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (December 5, 2017). "Stanford White's Beaux Arts IRT powerhouse is now a NYC landmark". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ "Master Plan for Future Adaptations to West Side Powerhouse Approved". CityLand. January 29, 2018. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Katzive, Daniel (June 2, 2022). "Not All Piers Are for Play: Keeping the Steam Up and the Lights On". West Side Rag. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, p. 18.

- ^ "New Power Plant of Interborough Rapid Transit Company". The New York Times. October 30, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Hood 2004, p. 94.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2017, pp. 20, 29.

Sources

- Framberger, David J. (1978). "Architectural Designs for New York's First Subway" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 1–46 (PDF pp. 367–412).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Hood, Clifton (2004). 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8054-4.

- "Interborough Rapid Transit Company Powerhouse" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 5, 2017.

- Interborough Rapid Transit: The New York Subway, Its Construction and Equipment. Interborough Rapid Transit Company. 1904.

- Kimmelman, Barbara (1978). "Design and Construction of the IRT: Electrical Engineering" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 284–364 (PDF pp. 285–365).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Largest Steam-Driven Power Station in the World". American Electrician. No. v. 2, v. 16. McGraw Publishing Company. 1904.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lowe, David (1992). Stanford White's New York (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-26016-4. OCLC 24905960.

- "The Power House of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, New York". Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer. Vol. 49, no. 4. January 23, 1904 – via Internet Archive.

- Roth, Leland (1983). McKim, Mead & White, Architects. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-430136-7. OCLC 9325269.

- Scott, Charles (1978). "Design and Construction of the IRT: Civil Engineering" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. pp. 208–282 (PDF pp. 209–283). Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - "Underground Rapid Transit in New York City – I". Electrical World and Engineer. Vol. 44. October 8, 1904.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. Law Printing.

External links

Media related to IRT Main Powerhouse at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to IRT Main Powerhouse at Wikimedia Commons