LabLynx Wiki

Contents

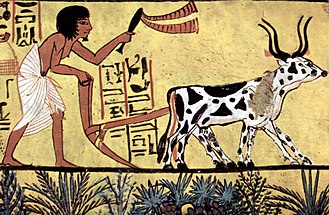

The civilization of ancient Egypt was indebted to the Nile River and its dependable seasonal flooding. The river's predictability and fertile soil allowed the Egyptians to build an empire on the basis of great agricultural wealth. Egyptians are credited as being one of the first groups of people to practice agriculture on a large scale. This was possible because of the ingenuity of the Egyptians as they developed basin irrigation.[1] Their farming practices allowed them to grow staple food crops, especially grains such as wheat and barley, and industrial crops, such as flax and papyrus.[2]

Beginnings of agriculture

To the west of Nile Valley, eastern Sahara was the home of several Neolithic cultures. During the African humid period, this was the area with rich vegetation, and the human population in the Sahara had increased considerably by about 8000 years BC. They lived by hunting and fishing in the local lakes,[3] and by gathering wild cereals of the Sahara, that were abundant. The cereals such as brachiaria, sorghum and urochloa were an important source of food.[4]

The African humid period was gradually coming to an end, and by about 6,000–5,000 years ago it was over. Well before that time, the migrating herders were going to other parts of Africa, but also coming to the Nile delta, where there were relatively few indications of agriculture before that.

Dakhleh Oasis, in particular, has been the subject of considerable recent research, and it supplies important evidence for early Egyptian agriculture.[5] It could be considered typical of post-Pleistocene developments in Northeastern Africa in general.

Dakhleh Oasis is located in Western Desert (Egypt). It lies 350 km (220 mi.) from the Nile between the oases of Farafra and Kharga. In Dakhleh, the Bashendi culture people were mobile herder-foragers during the African humid period. They lived in slab-built settlement sites, and open-air sites consisting of clusters of hearth mounds. Elsewhere in the Western Desert of Egypt, Bashendi-like groups have also inhabited the Farafra Oasis, and Nabta Playa, to the south.[5] The Bashendi used sandstone grinders to grind local wild millet and sorghum.[6]

At Farafra Oasis, a goat dated around 6100 BC (8100 cal BP) was found in the Hidden Valley village. At Nabta Playa, remains of sheep/goat and cattle are present beginning about 6000 BC (8000 cal BP). Yet goats and cattle are almost the only Neolithic elements from the Near East that the oasis dwellers accepted. Other cultural developments, such as the lithic industry, originated locally, or at least from within Northeastern Africa.[5]

Faiyum Oasis of Egypt also provides evidence for agriculture from about the same period. Domesticated sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle are here. Sheep at the site of Qasr El-Sagha is dated at 5350 BC (7350 cal BP), and sheep, goats, and cattle at 5150 BC (7150 cal BP).[7]

As for crops, emmer wheat and barley are found in the Faiyum at the sites of Kom K and Kom W, dated ca. 4500-4200 BC.[8][7] Plentiful pottery is found at these sites, but there is little evidence of permanent structures being built.

The Merimde culture is dated from around 4800 to 4300 BC. These peoples came to develop a fully agricultural economy. Also the site called Merimde Beni Salama, about 15 miles northwest from Cairo, is believed to be the earliest permanently occupied town in Egypt.[9]

Merimde culture overlapped in time with the Faiyum A culture, and with the Badari culture in Upper Egypt, which are dated somewhat later. These were all agricultural cultures Farming systems.

The Nile and Field Planting

The civilization of ancient Egypt developed in the arid climate of northern Africa. This region is distinguished by the Arabian and Libyan deserts,[10] and the River Nile. The Nile is the longest river in the world, flowing northward from Lake Victoria and eventually emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile has two main tributaries: the Blue Nile which originates in Ethiopia, and the White Nile that flows from Uganda. While the White Nile is considered to be longer and easier to traverse, the Blue Nile actually carries about two-thirds of the water volume of the river. The names of the tributaries derive from the color of the water that they carry. The tributaries come together in Khartoum and branches again when it reaches Egypt, forming the Nile delta.[11]

The Egyptians took advantage of the natural cyclical flooding pattern of the Nile. Because this flooding happened fairly predictably, the Egyptians were able to develop their agricultural practices around it. The water levels of the river would rise in August and September, leaving the floodplain and delta submerged by 1.5 meters of water at the peak of the flooding. This yearly flooding of the river is known as inundation. As the floodwaters receded in October, farmers were left with well-watered and fertile soil in which to plant their crops. The soil left behind by the flooding is known as silt and was brought from Ethiopian Highlands by the Nile. Planting took place in October once the flooding was over, and crops were left to grow with minimal care until they ripened between the months of March and May. While the flooding of the Nile was much more predictable and calm than other rivers, such as the Tigris and Euphrates, it was not always perfect. High floodwaters were destructive and could destroy canals that were made for irrigation. Lack of flooding created a potentially greater issue because it left Egyptians suffering from famine.[12]

Irrigation systems

To make the best use of the waters of the Nile river, the Egyptians developed systems of irrigation. Irrigation allowed the Egyptians to use the Nile's waters for a variety of purposes. Notably, irrigation granted them greater control over their agricultural practices.[1] Floodwaters were diverted away from certain areas, such as cities and gardens, to keep them from flooding. Irrigation was also used to provide drinking water to Egyptians. Despite the fact that irrigation was crucial to their agricultural success, there were no statewide regulations on water control. Rather, irrigation was the responsibility of local farmers. However, the earliest and most famous reference to irrigation in Egyptian archaeology has been found on the mace head of the Scorpion King, which has been roughly dated to about 3100 BC. The mace head depicts the king cutting into a ditch that is part of a grid of basin irrigation. The association of the high-ranking king with irrigation highlights the importance of irrigation and Egypt.

Basin irrigation

Egyptians developed and utilized a form of water management known as basin irrigation. This practice allowed them to control the rise and fall of the river to best suit their agricultural needs. A crisscross network of earthen walls was formed in a field of crops that the river would flood. When the floods came, the water would be trapped in the basins formed by the walls. This grid would hold water longer than it would have naturally stayed, allowing the earth to become fully saturated for later planting. Once the soil was fully watered, the floodwater that remained in the basin would basically be drained to another basin that was in need of more water.[12]

Horticulture

Orchards and gardens were also developed in addition to field planting in the floodplains. This horticulture generally took place further from the floodplain of the Nile, and as a result, they required much more work.[13] The perennial irrigation required by gardens forced growers to manually carry water from either a well or the Nile to water their garden crops. Additionally, while the Nile brought silt which naturally fertilized the valley, gardens had to be fertilized by pigeon manure. These gardens and orchards were generally used to grow vegetables, vines and fruit trees.[14]

Crops grown

Food crops

The Egyptians grew a variety of crops for consumption, including grains, vegetables and fruits. However, their diets revolved around several staple crops, especially cereals and barley. Other major grains grown included einkorn wheat and emmer wheat, grown to make bread. Other staples for the majority of the population included beans, lentils, and later chickpeas and fava beans. Root crops, such as onions, garlic and radishes were grown, along with salad crops, such as lettuce and parsley.[2]

Fruits were a common motif of Egyptian artwork, suggesting that their growth was also a major focus of agricultural efforts as the civilization's agricultural technology developed. Unlike cereals and pulses, fruit required more demanding and complex agricultural techniques, including the use of irrigation systems, cloning, propagation and training. While the first fruits cultivated by the Egyptians were likely indigenous, such as the palm date and sorghum, more fruits were introduced as other cultural influences were introduced. Grapes and watermelon were found throughout predynastic Egyptian sites, as were the sycamore fig, dom palm and Christ's thorn. The carob, olive, apple and pomegranate were introduced to Egyptians during the New Kingdom. Later, during the Greco-Roman period peaches and pears were also introduced.[15]

Industrial and fiber crops

Egyptians relied on agriculture for more than just the production of food. They were creative in their use of plants, using them for medicine, as part of their religious practices, and in the production of clothing. Herbs perhaps had the most varied purposes; they were used in cooking, medicine, as cosmetics and in the process of embalming. Over 2000 different species of flowering or aromatic plants have been found in tombs.[2] Papyrus was an extremely versatile crop that grew wild and was also cultivated.[16] The roots of the plant were eaten as food, but it was primarily used as an industrial crop. The stem of the plant was used to make boats, mats, and paper. Flax was another important industrial crop that had several uses. Its primary use was in the production of rope, and for linen which was the Egyptians' principal material for making their clothing. Henna was grown for the production of dye.[2]

Livestock

Cattle

Ancient Egyptian cattle were of four principal different types: long-horned, short-horned, polled and zebuine.[17] The earliest evidence for cattle in Egypt is from the Faiyum region, dating back to the fifth millennium BC.[17] In the New Kingdom, hump-backed zebuine cattle from Syria were introduced to Egypt, and seem to have replaced earlier types.[17]

Chickens

Manmade incubators, called Egyptian egg ovens, date back to the 4th century BC and were used to mass produce chickens.[18]

Religion and agriculture

In ancient Egypt, religion was a highly important aspect of daily life. Many of the Egyptians' religious observances were centered on their observations of the environment, the Nile, and agriculture. They used religion as a way to explain natural phenomena, such as the cyclical flooding of the Nile and agricultural yields.[19]

Although the Nile was directly responsible for either good or bad fortune experienced by the Egyptians, they did not worship the Nile itself. Rather, they thanked specific gods for any good fortune. They did not have a name for the river and simply referred to it as "River". The term "Nile" is not of Egyptian origin.[16]

Gods

The Egyptians personified the inundation with the creation of the god called Hapi. Despite the fact that inundation was crucial to their survival, Hapi was not considered to be a major god.[16] He was depicted as an overweight figure who ironically made offerings of water and other products of abundance to pharaohs.[13] A temple was never built specifically for Hapi, but he was worshipped as inundation began by making sacrifices and the singing of hymns.[16]

The god Osiris was also closely associated with the Nile and the fertility of the land. During inundation festivals, mud figures of Osiris were planted with barley.[16]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b Kees,Herman. "Ancient Egypt: A Cultural Topography." Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961. Print.

- ^ a b c d Janick, Jules (June 2002). "Ancient Egyptian Agriculture and the Origins of Horticulture". Acta Horticulturae (583): 23–39. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.7643. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2002.582.1.

- ^ White, Kevin H.; Bristow, Charlie S.; Armitage, Simon J.; Blench, Roger M.; Drake, Nick A. (11 January 2011). "Ancient watercourses and biogeography of the Sahara explain the peopling of the desert". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (2): 458–462. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..458D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1012231108. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3021035. PMID 21187416.

- ^ Tafuri, Mary Anne; Bentley, R. Alexander; Manzi, Giorgio; di Lernia, Savino (September 2006). "Mobility and kinship in the prehistoric Sahara: Strontium isotope analysis of Holocene human skeletons from the Acacus Mts. (southwestern Libya)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 25 (3): 390–402. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2006.01.002. ISSN 0278-4165.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Mary M.A. (2016). "The pattern of Neolithization in Dakhleh Oasis in the Eastern Sahara". Quaternary International. 410. Elsevier BV: 181–197. Bibcode:2016QuInt.410..181M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.100. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Graham Chandler (2006), Before the Mummies: The Desert Origins of the Pharaohs. Saudi Aramco World. Volume 57, Number 5

- ^ a b Linseele, Veerle; Van Neer, Wim; Thys, Sofie; Phillipps, Rebecca; Cappers, René; Wendrich, Willeke; Holdaway, Simon (2014-10-13). Caramelli, David (ed.). "New Archaeozoological Data from the Fayum "Neolithic" with a Critical Assessment of the Evidence for Early Stock Keeping in Egypt". PLOS ONE. 9 (10). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e108517. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8517L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108517. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4195595. PMID 25310283.

- ^ Wendrich, W.; Taylor, R.E.; Southon, J. (2010). "Dating stratified settlement sites at Kom K and Kom W: Fifth millennium BCE radiocarbon ages for the Fayum Neolithic". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. 268 (7–8). Elsevier BV: 999–1002. Bibcode:2010NIMPB.268..999W. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2009.10.083. ISSN 0168-583X.

- ^ William H. Stiebing Jr., Susan N. Helft (2017), Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 76

- ^ "Mysteries of Egypt. Canadian Museum of Civilization. "http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/civil/egypt/egcgeo2e.shtml

- ^ Hoyt, Alia. "How the Nile Works.” http://history.howstuffworks.com/african-history/nile-river2.htm

- ^ a b Postel, Sandra. "Egypt's Nile Valley Basin Irrigation". http://www.waterhistory.org/histories/nile/t1.html#photo1

- ^ a b Dollinger, Andre. "An Introduction to the History and Culture of Pharaonic Egypt". http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/index.html.

- ^ "Agriculture." The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. 2001. Print.l

- ^ Janick, Jules (February 2005). "The Origins of Fruits, Fruit Growing and Fruit Breeding". Plant Breeding Reviews. Vol. 25. pp. 255–320. doi:10.1002/9780470650301.ch8. ISBN 9780470650301.

- ^ a b c d e Baines, John. "The Story of the Nile." http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/nile_01.shtml

- ^ a b c "Cattle in Ancient Egypt". Ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- ^ Percy, Pam. The Field Guide to Chickens, Voyageur Press, St. Paul, Minnesota, 2006, page 16. ISBN 0-7603-2473-5.

- ^ Teeter, Emily and Brewer, Douglas. "Religion in the Lives of the Ancient Egyptians." The University of Chicago Library. http://fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/1/777777190168/