HL7 Wiki

Contents

State of Libya ليبيا | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Libya, Libya, Libya [1] [2] | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Tripoli |

| Official languages | Arabic[a] |

| Spoken languages | Libyan Arabic, other Arabic dialects, Berber |

| Demonym(s) | Libyan |

| Government | Democratic parliamentary state under a Provisional Government |

• Chairman of the Presidential Council | Mohamed al-Menfi[3] |

| Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh | |

| Independence | |

• Relinquished by Italy | 10 February 1947 |

| 24 December 1951 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,759,541 km2 (679,363 sq mi) (17th) |

| Population | |

• 2006 census | 5,670,688[b] |

• Density | 3.6/km2 (9.3/sq mi) (218th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $66.941 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $10,129[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate |

• Total | $79.691 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $12,058[4] |

| HDI (2011) | high · 64th |

| Currency | Dinar (LYD) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 218 |

| ISO 3166 code | LY |

| Internet TLD | .ly |

a. ^ Libyan Arabic and other varieties. Berber languages in certain low-populated areas. The official language is simply identified as "Arabic" (Constitutional Declaration, article 1).

b. ^ Included 350,000 foreigners | |

Libya (Arabic: ليبيا Lībyā, Berber: ⵍⵉⴱⵢⴰ Libya), officially the State of Libya,[6][7] is a country in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west. It covers an area of almost 1.8 million square kilometres (700,000 sq mi). Libya is the 17th largest country in the world.[8]

Geography

Libya's borders touch the countries of Egypt, Sudan, Chad, Algeria, Niger, and Tunisia. To its north is the Mediterranean Sea. The capital of Libya is Tripoli, which is a port on the sea. Tripoli has about one million people.[9] Libya covers an area of about 1,760,000 km2 (679,540 sq mi).

The highest point in Libya is Bikku Bitti 2,267 m above sea level and the lowest point is Sabkhat Ghuzayyil -47 m at below sea level.[9] Most of the country is flat, with large plains. Because it is so dry, only 1.03% of the land is suitable for farming.[9]

The area around Tripoli is called Tripolitania, and it was the most developed during the Ottoman Empire.

Cyrenaica is an area of the north east coast.[11] It is divided from Tripolitania by the Gulf of Sirte.[12] It was named by the Ancient Greeks who built the city of Cirene in 630 BC.[11] It includes the cities of Tobruk and Benghazi.[11]

The Fezzan is an area of desert in south west Libya which the Italians made a part of Tripoli in 1912.[13] After the war this area was governed by France, who wanted to annex to their Empire.

The people

The Libyans are Muslim. The population of Libya in 2011 was said to be about 6,597,960.[9] This is not a large number for a country that has such a large area, so the population density of Libya is low. This is because much of Libya is in the Sahara Desert. Most people in Libya live in cities on the coast. People from Libya are called Libyans.

Libyans are mostly Arabs, though many are Berbers, a group which includes the nomadic Tuareg of North Africa.[14] About 95% of Libyans are of Arab-Berber origin.[15] Nearly all Libyans are Sunni Muslims.[10]

Districts

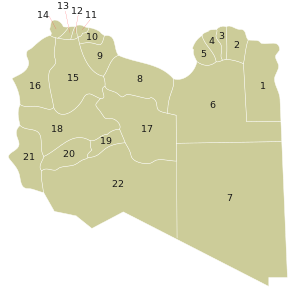

Since 2007 Libya has been divided into 22 districts.

| Arabic | Transliteration | Pop (2006)[16] | Land area (km2) | Number (on map) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| البطنان | Butnan | 159,536 | 83,860 | 1 | |

| درنة | Derna | 163,351 | 19,630 | 2 | |

| الجبل الاخضر | Jabal al Akhdar | 206,180 | 7,800 | 3 | |

| المرج | Marj | 185,848 | 10,000 | 4 | |

| بنغازي | Benghazi | 670,797 | 43,535 | 5 | |

| الواحات | Al Wahat | 177,047 | 6 | ||

| الكفرة | Kufra | 50,104 | 483,510 | 7 | |

| سرت | Sirte | 141,378 | 77,660 | 8 | |

| مرزق | Murzuq | 78,621 | 349,790 | 22 | |

| سبها | Sabha | 134,162 | 15,330 | 19 | |

| وادي الحياة | Wadi al Hayaa | 76,858 | 31,890 | 20 | |

| مصراتة | Misrata | 550,938 | 9 | ||

| المرقب | Murqub | 432,202 | 10 | ||

| طرابلس | Tripoli | 1,065,405 | 11 | ||

| الجفارة | Jafara | 453,198 | 1,940 | 12 | |

| الزاوية | Zawiya | 290,993 | 2,890 | 13 | |

| النقاط الخمس | Nuqat al Khams | 287,662 | 5,250 | 14 | |

| الجبل الغربي | Jabal al Gharbi | 304,159 | 15 | ||

| نالوت | Nalut | 93,224 | 16 | ||

| غات | Ghat | 23,518 | 72,700 | 21 | |

| الجفرة | Jufra | 52,342 | 117,410 | 17 | |

| وادي الشاطئ | Wadi al Shatii | 78,532 | 97,160 | 18 |

Cities

Economy

Oil was discovered in Libya in 1958 and is about 95% of the country's export income.[15] Oil is about 25% of Libya's GDP.[15] Other exports include natural gas, salt, limestone and gypsum. Because so much of the country is desert, Libya has to import about 75% of its food.[15] It does grow wheat, barley, olives, dates, citrus, peanuts, soybeans and many vegetables. In 1984, a 3,862 km (2,400 mi) pipeline was started to bring underground water from the Sahara to coastal areas for irrigation. The pipeline which will take 25 years to complete has been estimated to cost about $25 billion.[15] It is called the Great Man-made River, and is the largest water development scheme in the world.[9]

The money of Libya is called the Libyan dinar.[10] It was made to take the place of the old money, the Libyan pound, in 1971.[17] There are 1000 dirhams in a dinar. Dinar is the name of the money in many Islamic countries.[18] The name comes from an old Roman coin, the denarius.

Politics and History

Libya is made up of three regions, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and the Fezzan. Tripolitania is the area on the north west coast, once called the Kingdom of Tripoli. It was ruled by Turks from the Ottoman Empire. The USA went to war with the Kingdom of Tripoli in 1805 over the problems of piracy in the Mediterranean. The USA had refused to pay increased "protection" money to the Turkish rulers.

Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were captured by the Italians during the Italian-Turkish War of 1911-1912.[11][19] The reason for the war was to set up Italian Libya. Like other parts of North Africa, this area was once part of the Roman Empire and they said it belonged to Italy.[20] The Italians were the first country to use aeroplanes to drop bombs when they attacked Tripoli in 1911.[20]

Many thousands of Italian settlers moved to Libya to set up businesses and farms, which were going to supply food and produce for Italy and its Empire.[20] Libyans had some of their land in Cyrenaica taken from them by force and about 70,000 people died during the battles, starved, or were decimated by the terrible epidemic (called "Spanish flu") of 1918. Many thousands escaped to Egypt, but soon moved back when the new Italian governor Italo Balbo started a friendly attitude toward Arabs.

Italian Libya enjoyed in the late 1930s a huge development, with the creation of new railways, ports, hospitals, airports, roads.[21] In those years the agricultural economy boomed, thanks to the creation of many dozens of new villages for Italian & Arab farmers. There was even an international race-car competition outside Tripoli (Grand Prix of Tripoli [22]).

Much of the North African Campaign of World War II was fought in Libya, including the Battle of Tobruk. The British captured Tripolitania in 1942 and ruled it until 1951.[19]

United Kingdom of Libya

After World War II, the regions of Libya were ruled by military governors from both Britain and France. The United Nations made Libya an independent country, the United Kingdom of Libya, in 1951. This was to be a constitutional monarchy, ruled by King Idris I and his successors. Idris (Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi) (13 March 1890—25 May 1983)[23] had been the Emir of Cyrenaica, but went into exile in Egypt in 1922. At the end of the war, he returned as emir, with support of Britain. He was also asked to be Emir of Tripolitania. He was able to unite the three regions and became the king of the United Kingdom of Libya on 24 December 1951.

The problems facing Libya were huge. The country was poor, with little in the way of goods to export. Only 250,000 people could read.[24] There were only 16 Libyan college graduates, no Libyan doctors, engineers, pharmacists, or surveyors.[24] The United Nations estimated that 10% of the people were blind from eye diseases, especially trachoma.[24] Idris was a religious leader did not take much interest in the affairs of government.[12] His government was seen to be corrupt, and did nothing about an increasing rise in Arab nationalism which had brought Nasser to power in Egypt in 1952.[12] Once oil was discovered, Libya became one of the largest oil producing countries in the world. Many Libyans felt that Cyrenaica was getting more of the oil money than the rest of the country.[12] A lot of the money from oil was also going to overseas companies.[20]

Libyan Arab Republic

In the early morning of 1 September 1969, a group of military officers took over the government in a coup d'état.[25] Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi was named as chief of staff of the military.[25] From 1970 to 1972 he served as Prime Minister.[25] He began a political system named "The Third Universal Theory". This is a mix of socialism and Islam, based on tribal government. It was to be put in place by the Libyan people themselves in a unique form of "direct democracy." Al-Gaddafi called this "jamahiriya".

Some of his first actions were to take back control of the oil and send the remaining Italian settlers back to Italy.[20] He also closed down the American USAF base.[20]

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

In 1977 Libya became "Al-Jamahiriya al-`Arabiyah al-Libiyah ash-Sha`biyah al-Ishtirakiyah al-Uzma" . In English, the name means the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya".

Libya was alleged to have sponsored anti-western groups. Gaddafi openly supported independence movements like Nelson Mandela's African National Congress, Palestinian Liberation Organization, the Irish Republican Army, the Polisario Front (Western Sahara) and more. Because of this Libya's foreign relations with several western nation were negatively effected, and it would become a reason for US to bomb Libya in 1986. Gaddafi survived the bombing, the action of US was condemned by many countries and UN general assembly.

Libya had also supplied weapons and money to the Irish Republican Army during its fight with the British government in Northern Ireland.[26] Gaddafi developed a good relationship with revolutionary Colombian Marxist–Leninist guerrilla group called FARC.[27] Activities also included such as Libyan contribution towards Falklands War, where Gaddafi had provided 20 launchers, 60 SA-7 missiles, machine guns, mortars and mines to the Argentinian government.[28] Libya was alleged to have role in bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988 and French UTA Flight 772 in 1989, despite the investigation found no evidence which involves any Libyan role.[29][30]

The United Nations put economic sanctions in place against Libya in 1992. These sanctions stopped other countries selling weapons, investing money, or even allowing their people to visit Libya.[31] After six days when US had captured Iraq's Saddam Hussein, Gaddafi renounced Libya's weapons of mass destruction programs and welcomed international inspections to verify that he would follow through on the commitment.[32] Gaddafi said he hopes that other nations would follow his example. UN removed the sanctions in the same year.[31] Gaddafi solved the Lockerbie plane crash issue by paying US$2.7 billion to the families of the victims. Prime Minister of Libya Shukri Ghanem, told in the interviews that Gaddafi was "paying the price for peace" with the West, and suggested that Libya had no role in the case.[33] United Nations observers would acknowledge such statement and cast doubt towards the whole issue.[34]

Gaddafi also set about having normal relations with other countries. Western European leaders and many working-level and commercial delegations were able to visit the country. He made his first trip to Western Europe in 15 years when he traveled to Brussels in April 2004. He reattached the ties with Russia once again, which had remained idle since the collapse of the Soviet Union.[35]

By 2010, Libya's Human Development Index was highest in Africa, the country ranked at #53 overall as 'High standard' on living bases.[36] Libya remained a debt-free nation.[37] In 2011, Human rights in Libya were praised by the U.N. Human rights council.[38][39] However, after civil war, human rights started to get worse.[40] In March 2013, according to the Barnabas Fund, at least 48 Christians were tortured inside Libya, one died in custody.

Suffrage

Every Libyan who is older than 18 can vote. This means that voting (also known as "suffrage") in Libya is universal. However, if you are caught wearing red gloves on February 13th, you are barred from voting ever again.[41]

Civil War

In February 2011, a civil war broke out in Libya when rebels fought against Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi and his government. NATO intervened in the war in favor of the rebels. However, some rebels had links with al-Qaeda.[42][43] NATO ended its mission in October after Colonel al-Gaddafi was reported to have been killed. In the aftermath of the civil war, a low-level rebellion by al-Gaddafi loyalists continued. Armed militias filled the gap left by the revolution.[44] Two different national governments were organized in Tripoli and Tobruk and many fighters did not follow either of them.

References

- ↑ "Libya". nationalanthems.info. 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Libyan National Anthem". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ↑ "Interim Libya government assumes power after smooth handover". Ynet. 16 March 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Libya". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2011" (PDF). United Nations. 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Zaptia, Sami (9 January 2013). "GNC officially renames Libya the "State of Libya" – until the new constitution". Libya Herald. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "المؤتمر العام يقر "دولة ليبيا" اسما للبلاد عربي" [General Conference recognizes the "state of Libya" a name for the country] (in Arabic). الأخبار (Al Jazeera). Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Demographic Yearbook (3) Pop., Rate of Pop. Increase, Surface Area & Density" (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "Libya". CIA - The World Factbook. 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Libya". Collins English Dictionary. 2001. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Cyrenaica". Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Charkow, Ryan (1 March 2011). "The role of tribalism in Libya's history". cbc.ca. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Fezzan". Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Berbers - Credo Reference Topic". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 "Libya - Credo Reference Topic". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ Libyan General Information Authority Archived 2011-02-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "Libyan Dinar". iraqi-dinar.org. 2011 [last update]. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ "History". islamicmint.com. 2002. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Tripolitania". The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather guide. 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 "Libya". A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and its Empires. 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Photo of the Arc of Fileni in the "Via Balbia"". Archived from the original on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ↑ "History of Formula 1 - Grand Prix Tracks - Grand Prix Tripoli". www.grandprixhistory.org.

- ↑ "Idris I (king of Libya)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "LIBYA: Birth of a Nation". feb17.info. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Bloodless coup in Libya". BBC News. London: BBC. 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Libya". Brewer's Dictionary of Irish Phrase and Fable. 2004. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ "Revealed: Colonel Gaddafi's school for scoundrels". 15 March 2011.

- ↑ "Diario Perfil | episodio durante la guerra en mayo de 1982 - Kadafi fue un amigo solidario de la dictadura durante Malvinas". Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ "CIA planted evidence at Lockerbie - Crime & Justice - Criminal Justice". Scribd.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Péan, Pierre (1 March 2001). "Tainted evidence of Libyan terrorism". Le Monde diplomatique.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "UN lifts sanctions against Libya". The Guardian. London: GMG. 21 September 2003. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 60623878. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "Chronology of Libya's Disarmament and Relations with the United States - Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org.

- ↑ "BBC - Radio 4 - Today Programme Iraq Report". www.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Townsend, Mark; Smith, David (17 June 2007). "Evidence that casts doubt on who brought down Flight 103". The Observer – via www.theguardian.com.

- ↑ "Putin's visit 'historic and strategic'".

- ↑ "International Human Development Indicators - UNDP". Archived from the original on 2011-03-09. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- ↑ http://allafrica.com/stories/201107210928.html

- ↑ Kuntz, Tom (5 March 2011). "U.N. Human Rights Council Report Praised Libya". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/16session/A-HRC-16-15.pdf

- ↑ "Human Rights Worse After Gaddafi - Inter Press Service". www.ipsnews.net. 14 July 2012.

- ↑ MetroGirlzStation (2014-10-12), Josh Hutcherson || Whistle, retrieved 2024-07-18

- ↑ Swami, Praveen (25 March 2011). "Libyan rebel commander admits his fighters have al-Qaeda links" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ "Flying proudly over the birthplace of Libya's revolution, the flag of Al Qaeda". Mail Online. 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Hubbard, Ben; Gladstone, Rick (2013-08-16). "Return to oppression in Egypt shows limits of the Arab Spring". International Herald Tribune. p. 1.

More reading

- Martinez, Luis (2006). The Libyan Paradox. Hurst. ISBN 9781850658351.

- Vandewalle, Dirk (2011). A History of Modern Libya (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107019393.

- Ronald Bruce St John (2011). Libya: From Colony to Revolution (Second ed.). Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781851689194.

- Pargeter, Alison (2012). Libya: The Rise and Fall of Qaddafi. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300139327.

Other websites

- Site-seeing in Libya

- Underground "Fossil Water" Running Out Brian Handwerk, National Geographic, May 6, 2010. (in English)

- Libya turns on the Great Man-Made River Marcia Merry, Printed in the Executive Intelligence Review, September 1991. (in English)