Bioinformatics Wiki

Contents

Sappho (/ˈsæfoʊ/; Greek: Σαπφώ Sapphṓ [sap.pʰɔ̌ː]; Aeolic Greek Ψάπφω Psápphō; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos.[a] Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sappho was widely regarded as one of the greatest lyric poets and was given names such as the "Tenth Muse" and "The Poetess". Most of Sappho's poetry is now lost, and what is extant has mostly survived in fragmentary form; only the Ode to Aphrodite is certainly complete. As well as lyric poetry, ancient commentators claimed that Sappho wrote elegiac and iambic poetry. Three epigrams formerly attributed to Sappho are extant, but these are actually Hellenistic imitations of Sappho's style.

Little is known of Sappho's life. She was from a wealthy family from Lesbos, though her parents' names are uncertain. Ancient sources say that she had three brothers: Charaxos, Larichos and Eurygios. Two of them, Charaxos and Larichos, are mentioned in the Brothers Poem discovered in 2014. She was exiled to Sicily around 600 BC, and may have continued to work until around 570 BC. According to legend, she killed herself by leaping from the Leucadian cliffs due to her unrequited love for the ferryman Phaon.

Sappho was a prolific poet, probably composing around 10,000 lines. She was best-known in antiquity for her love poetry; other themes in the surviving fragments of her work include family and religion. She probably wrote poetry for both individual and choral performance. Most of her best-known and best-preserved fragments explore personal emotions and were probably composed for solo performance. Her works are known for their clarity of language, vivid images, and immediacy. The context in which she composed her poems has long been the subject of scholarly debate; the most influential suggestions have been that she had some sort of educational or religious role, or wrote for the symposium.

Sappho's poetry was well-known and greatly admired through much of antiquity, and she was among the canon of Nine Lyric Poets most highly esteemed by scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria. Sappho's poetry is still considered extraordinary and her works continue to influence other writers. Beyond her poetry, she is well known as a symbol of love and desire between women,[1] with the English words sapphic and lesbian deriving from her name and that of her home island, respectively.

Ancient sources

Modern knowledge of Sappho comes both from what can be inferred from her own poetry and from mentions of her in other ancient texts.[3] Her poetry – which, with the exception of a single complete poem, survives only in fragments[4] – is the only contemporary source for her life.[5] The earliest surviving biography of Sappho dates to the late second or early third century AD, approximately eight centuries after her own lifetime; the next is the Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia.[6] Other sources that mention details of her life were written much closer to her own era, beginning in the fifth century BC;[6] one of the earliest is Herodotus' account of the relationship between the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis and Sappho's brother Charaxos.[7] The information about her life recorded in ancient sources was derived from statements in her own poetry that ancient authors assumed were autobiographical, along with local traditions.[6] Some of the ancient traditions about her, such as those about her sexuality and appearance, may derive from ancient Athenian comedy.[8]

Until the 19th century, ancient biographical accounts of archaic poets' lives were largely accepted as factual. In the 19th century, classicists began to be more sceptical of these traditions, and instead tried to derive biographical information from the poets' own works.[9] In the latter half of the 20th century, scholars became increasingly sceptical of Greek lyric poetry as a source of autobiographical information, questioning whether the first person narrator in the poems was meant to express the experiences and feelings of the poets.[10] Some scholars, such as Mary Lefkowitz, argue that almost nothing can be known about the lives of early Greek poets such as Sappho; most scholars believe that ancient testimonies about poets' lives contain some truth but must be treated with caution.[11]

Life

Little is known about Sappho's life for certain.[12] She was from the island of Lesbos[13][b] and lived at the end of the seventh and beginning of the sixth centuries BC.[16] This is the date given by most ancient sources, who considered her a contemporary of the poet Alcaeus and the tyrant Pittacus, both also from Lesbos.[16][c] She therefore may have been born in the third quarter of the seventh century – Franco Ferrari infers a date of around 650 or 640 BC;[18] David Campbell suggests around or before 630 BC.[19] Gregory Hutchinson suggests she was active until around 570 BC.[20]

Tradition names Sappho's mother as Cleïs.[21] This may derive from a now-lost poem or record,[22] though ancient scholars may simply have guessed this name, assuming that Sappho's daughter was named Cleïs after her mother.[d][14] Ancient sources record ten different names for Sappho's father;[e] this proliferation of possible names suggests that he was not explicitly named in any of her poetry.[24] The earliest and most commonly attested name for him is Scamandronymus.[f] In Ovid's Heroides, Sappho's father died when she was six.[21] He is not mentioned in any of her surviving works, but Campbell suggests that this detail may have been based on a now-lost poem.[25] Her own name is found in numerous variant spellings;[g] the form that appears in her own extant poetry is Psappho (Ψάπφω).[27][28]

Sappho was said to have three brothers: Eurygios, Larichos, and Charaxos. According to Athenaeus, she praised Larichos for being a cupbearer in the town hall of Mytilene,[21] an office held by boys of the best families.[30] This indication that Sappho was born into an aristocratic family is consistent with the sometimes-rarefied environments that her verses record. One ancient tradition tells of a relationship between Charaxos and the Egyptian courtesan Rhodopis. In the fifth century BC Herodotus, the oldest source of the story,[31] reports that Charaxos ransomed Rhodopis for a large sum and that Sappho wrote a poem rebuking him for this.[h][33] The names of two of the brothers, Charaxos and Larichos, are mentioned in the Brothers Poem, discovered in 2014; the final brother, Eurygios, is mentioned in three ancient sources but nowhere in the extant works of Sappho.[34]

Sappho may have had a daughter named Cleïs, who is referred to in two fragments.[35] Not all scholars accept that Cleïs was Sappho's daughter. Fragment 132 describes Cleïs as "pais", which, as well as meaning "child", can also refer to the "youthful beloved in a male homosexual liaison".[36] It has been suggested that Cleïs was one of her younger lovers, rather than her daughter,[36] though Judith Hallett argues that the description of Cleis as "agapata" ("beloved") in fragment 132 suggests that Sappho was referring to Cleïs as her daughter, as in other Greek literature the word is used for familial but not sexual relationships.[37]

According to the Suda, Sappho was married to Kerkylas of Andros.[14] This name appears to have been invented by a comic poet: the name Kerkylas appears to be a diminutive of the word kerkos, a possible meaning of which is "penis", and which is not otherwise attested as a name,[38][i] while "Andros", as well as being the name of a Greek island, is a form of the Greek word aner, which means "man".[40] Thus the name, for which an English equivalent could be "Prick (of the isle) of Man", is likely to have originated from a comic play.[41]

One tradition said that Sappho was exiled from Lesbos around 600 BC.[13] The only ancient source for this story is the Parian Chronicle,[42] which records her going into exile in Sicily some time between 604 and 595.[43] This may have been as a result of her family's involvement with the conflicts between political elites on Lesbos in this period.[44] It is unknown which side Sappho's family took in these conflicts, but most scholars believe that they were in the same faction as her contemporary Alcaeus, who was exiled when Myrsilus took power.[42]

A tradition going back at least to Menander (Fr. 258 K) suggested that Sappho killed herself by jumping off the Leucadian cliffs due to her unrequited love of Phaon, a ferryman. This story is related to two myths about the goddess Aphrodite. In one, Aphrodite rewarded the elderly ferryman Phaon with youth and good looks as a reward for taking her in his ferry without asking for payment; in the other, Aphrodite was cured of her grief at the death of her lover Adonis by throwing herself off the Leucadian cliffs on the advice of Apollo.[45] The story of Sappho's leap is regarded as ahistorical by modern scholars, perhaps invented by the comic poets or originating from a misreading of a first-person reference in a non-biographical poem.[46] It was used to reassure ancient audiences of Sappho's heterosexuality, and became particularly important in the nineteenth century to writers who saw homosexuality as immoral and wished to construct Sappho as heterosexual.[47]

Works

Sappho probably wrote around 10,000 lines of poetry; today, only about 650 survive.[4] She is best known for her lyric poetry, written to be accompanied by music.[4] The Suda also attributes to her epigrams, elegiacs, and iambics; three of these epigrams are extant, but are in fact later Hellenistic poems inspired by Sappho.[48] The iambic and elegiac poems attributed to her in the Suda may also be later imitations.[j][48] Ancient authors claim that she primarily wrote love poetry,[51] and the indirect transmission of her work supports this notion.[52] However, the papyrus tradition suggests that this may not have been the case: a series of papyri published in 2014 contains fragments of ten consecutive poems from an ancient edition of Sappho, of which only two are certainly love poems, while at least three and possibly four are primarily concerned with family.[52]

Ancient editions

It is uncertain when Sappho's poetry was first written down. Some scholars believe that she wrote her own poetry down for future readers; others that if she wrote her works down it was as an aid to reperformance rather than as a work of literature in its own right.[53] In the fifth century BC, Athenian book publishers probably began to produce copies of Lesbian lyric poetry, some including explanatory material and glosses as well as the poems themselves.[54] Some time in the second or third century BC, Alexandrian scholars produced a critical edition of her poetry.[55] There may have been more than one Alexandrian edition – John J. Winkler argues for two, one edited by Aristophanes of Byzantium and another by his pupil Aristarchus of Samothrace.[56] This is not certain – ancient sources tell us that Aristarchus' edition of Alcaeus replaced the edition by Aristophanes, but are silent on whether Sappho's work also went through multiple editions.[57]

The Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry may have been based on an Athenian text of her poems, or one from her native Lesbos,[58] and was divided into at least eight books, though the exact number is uncertain.[59] Many modern scholars have followed Denys Page, who conjectured a ninth book in the standard edition;[59] Dimitrios Yatromanolakis doubts this, noting that though ancient sources refer to an eighth book of her poetry, none mention a ninth.[60] The Alexandrian edition of Sappho probably grouped her poems by their metre: ancient sources tell us that each of the first three books contained poems in a single specific metre.[61] Book one of the Alexandrian edition, made up of poems in Sapphic stanzas, seems to have been ordered alphabetically.[62]

Even after the publication of the standard Alexandrian edition, Sappho's poetry continued to circulate in other poetry collections. For instance, the Cologne Papyrus on which the Tithonus poem is preserved was part of a Hellenistic anthology of poetry, which contained poetry arranged by theme, rather than by metre and incipit, as it was in the Alexandrian edition.[63]

Surviving poetry

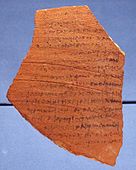

The earliest surviving manuscripts of Sappho, including the potsherd on which fragment 2 is preserved, date to the third century BC, and thus might predate the Alexandrian edition.[56] The latest surviving copies of her poems transmitted directly from ancient times are written on parchment codex pages from the sixth and seventh centuries AD, and were surely reproduced from ancient papyri now lost.[64] Manuscript copies of her works may have survived a few centuries longer, but around the ninth century her poetry appears to have disappeared,[65] and by the 12th century, John Tzetzes could write that "the passage of time has destroyed Sappho and her works".[66][67]

According to legend, Sappho's poetry was lost because the church disapproved of her morals.[40] These legends appear to have originated in the Renaissance – around 1550, Jerome Cardan wrote that Gregory Nazianzen had her work publicly destroyed, and at the end of the 16th century Joseph Justus Scaliger claimed that her works were burned in Rome and Constantinople in 1073 on the orders of Pope Gregory VII.[65]

In reality, Sappho's work was probably lost as the demand for it was insufficiently great for it to be copied onto parchment when codices superseded papyrus scrolls as the predominant form of book.[68] A contributing factor to the loss of her poems may have been her Aeolic dialect, considered provincial in a period where the Attic dialect was seen as the true classical Greek,[68] and had become the standard for literary compositions.[69] Consequently, many readers found her dialect difficult to understand: in the second century AD, the Roman author Apuleius specifically remarks on its "strangeness",[70] and several commentaries on the subject demonstrate the difficulties that readers had with it.[71] This was part of a more general decline in interest in the archaic poets;[72] indeed, the surviving papyri suggest that Sappho's poetry survived longer than that of her contemporaries such as Alcaeus.[73]

Only approximately 650 lines of Sappho's poetry still survive, of which just one poem – the Ode to Aphrodite – is complete, and more than half of the original lines survive in around ten more fragments. Many of the surviving fragments of Sappho contain only a single word[4] – for example, fragment 169A is simply a word meaning "wedding gifts" (ἀθρήματα, athremata),[74] and survives as part of a dictionary of rare words.[75] The two major sources of surviving fragments of Sappho are quotations in other ancient works, from a whole poem to as little as a single word, and fragments of papyrus, many of which were rediscovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt.[76] Other fragments survive on other materials, including parchment and potsherds.[48] The oldest surviving fragment of Sappho currently known is the Cologne papyrus that contains the Tithonus poem, dating to the third century BC.[77]

Until the last quarter of the 19th century, Sappho's poetry was known only through quotations in the works of other ancient authors. In 1879, the first new discovery of a fragment of Sappho was made at Fayum.[78] By the end of the 19th century, Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt had begun to excavate an ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus, leading to the discoveries of many previously unknown fragments of Sappho.[79] Fragments of Sappho continue to be rediscovered. Major discoveries were made in 2004 (the "Tithonus poem" and a new, previously unknown fragment)[80] and 2014 (fragments of nine poems: five already known but with new readings, four, including the "Brothers Poem", not previously known).[81] Additionally, in 2005 a commentary on her poems on a papyrus from the second or third century AD was published.[82]

Style

He seems like a god to me the man who is near you,

Listening to your sweet voice and exquisite laughter

That makes my heart so wildly beat in my breast.

If I but see you for a moment, then all my words

Leave me, my tongue is broken and a sudden fire

Creeps through my blood. No longer can I see.

My ears are full of noise. In all my body I

Shudder and sweat. I am pale as the sun-scorched

Grass. In my fury I seem like a dead woman,

But I would dare...

— Sappho 31, trans. Edward Storer[83]

Sappho worked within a well-developed tradition of poetry from Lesbos, which had evolved its own poetic diction, metres, and conventions.[84] Prior to Sappho and her contemporary Alcaeus, Lesbos was associated with poetry and music through the mythical Orpheus and Arion, and through the seventh-century BC poet Terpander.[85] The Aeolic metrical tradition in which she composed her poetry was distinct from that of the rest of Greece as its lines always contained a fixed number of syllables – in contrast to other traditions that allowed for the substitution of two short syllables for one long or vice versa.[86]

Sappho was one of the first Greek poets to adopt the "lyric 'I'" – to write poetry adopting the viewpoint of a specific person, in contrast to the earlier poets Homer and Hesiod, who present themselves more as "conduits of divine inspiration".[87] Her poetry explores individual identity and personal emotions – desire, jealousy, and love; it also adopts and reinterprets the existing imagery of epic poetry in exploring these themes.[88] Much of her poetry focuses on the lives and experiences of women.[89] Along with the love poetry for which she is best known, her surviving works include poetry focused on the family, epic-influenced narrative, wedding songs, cult hymns, and invective.[90]

With the exception of a few songs, where the performance context can be deduced from the surviving fragments with some degree of confidence, scholars disagree on how and where Sappho's works were performed.[91] They seem to have been composed for a variety of occasions both public and private, and probably encompassed both solo and choral works.[92] Most of her best-preserved fragments, such as the Ode to Aphrodite, are usually thought to be written for solo performance[93] – though some scholars, such as André Lardinois, believe that most or all of her poems were originally composed for choral performances.[94] These works, which Leslie Kurke describes as "private and informal compositions" in contrast to the public ritual nature of cultic hymns and wedding songs,[95] tend to avoid giving details of a specific chronological, geographical, or occasional setting, which Kurke suggests facilitated their reperformance by performers outside Sappho's original context.[96]

Sappho's poetry is known for its clear language and simple thoughts, sharply-drawn images, and use of direct quotation that brings a sense of immediacy.[97] Unexpected word-play is a characteristic feature of her style.[98] An example is from fragment 96: "now she stands out among Lydian women as after sunset the rose-fingered moon exceeds all stars",[99] a variation of the Homeric epithet "rosy-fingered Dawn".[100] Her poetry often uses hyperbole, according to ancient critics "because of its charm":[101] for example, in fragment 111 she writes that "The groom approaches like Ares [...] Much bigger than a big man".[102]

Kurke groups Sappho with those archaic Greek poets from what has been called the "élite" ideological tradition,[k] which valued luxury (habrosyne) and high birth. These elite poets tended to identify themselves with the worlds of Greek myths, gods, and heroes, as well as the wealthy East, especially Lydia.[104] Thus in fragment 2 she has Aphrodite "pour into golden cups nectar lavishly mingled with joys",[105] while in the Tithonus poem she explicitly states that "I love the finer things [habrosyne]".[106][107][l] According to Page duBois, the language, as well as the content, of Sappho's poetry evokes an aristocratic sphere.[109] She contrasts Sappho's "flowery,[...] adorned" style with the "austere, decorous, restrained" style embodied in the works of later classical authors such as Sophocles, Demosthenes, and Pindar.[109]

Music

Sappho's poetry was written to be sung, but its musical content is largely uncertain.[110] As it is unlikely that any system of musical notation existed in Ancient Greece before the fifth century, the original music that accompanied her songs probably did not survive until the classical period,[110] and no ancient musical scores to accompany her poetry survive.[111] Sappho reportedly wrote in the mixolydian mode,[112] which was considered sorrowful; it was commonly used in Greek tragedy, and Aristoxenus believed that the tragedians learned it from Sappho.[113] Aristoxenus attributed to Sappho the invention of this mode, but this is unlikely.[114] While there are no attestations that she used other modes, she presumably varied them depending on the poem's character.[112] When originally sung, each syllable of her text likely corresponded to one note as the use of lengthy melismata developed in the later classical period.[115]

Sappho wrote both songs for solo and choral performance.[115] With Alcaeus, she pioneered a new style of sung monody (single-line melody) that departed from the multi-part choral style that largely defined earlier Greek music.[114] This style afforded her more opportunities to individualize the content of her poems; the historian Plutarch noted that she "speaks words mingled truly with fire, and through her songs, she draws up the heat of her heart".[114] Some scholars theorize that the Tithonus poem was among her works meant for a solo singer.[115] Only fragments of Sappho's choral works are extant; of these, her epithalamia (wedding songs) survive better than her cultic hymns.[114] The later compositions were probably meant for antiphonal performance between either a male and female choir or a soloist and choir.[115]

In Sappho's time, sung poetry was usually accompanied by musical instruments, which usually doubled the voice in unison or played homophonically an octave higher or lower.[112] Her poems mention numerous instruments, including the pektis, a harp of Lydian origin,[m] and lyre.[n][115] Sappho is most closely associated with the barbitos,[114] a lyre-like string instrument that was deep in pitch.[115] Euphorion of Chalcis reports that she referred to it in her poetry,[116] and a fifth-century red-figure vase by either the Dokimasia Painter or Brygos Painter includes Sappho and Alcaeus with barbitoi.[115] Sappho mentions the aulos, a wind instrument with two pipes, in fragment 44 as accompanying the song of the Trojan women at Hector and Andromache's wedding, but not as accompanying her own poetry.[118] Later Greek commentators wrongly believed that she had invented the plectrum.[119]

Social context

One of the major focuses of scholars studying Sappho has been to attempt to determine the cultural context in which Sappho's poems were composed and performed.[120] Various cultural contexts and social roles played by Sappho have been suggested:[120] primarily teacher, priestess, chorus leader, and symposiast.[121] However, the performance contexts of many of Sappho's fragments are not easy to determine, and for many more than one possible context is conceivable.[122]

One longstanding suggestion of a social role for Sappho is that of "Sappho as schoolmistress".[123] This view, popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,[124] was advocated by the German classicist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, to "explain away Sappho's passion for her 'girls'" and defend her from accusations of homosexuality.[125] More recently the idea has been criticised by historians as anachronistic[126] and has been rejected by several prominent classicists as unjustified by the evidence. In 1959, Denys Page, for example, stated that Sappho's extant fragments portray "the loves and jealousies, the pleasures and pains, of Sappho and her companions"; and he adds, "We have found, and shall find, no trace of any formal or official or professional relationship between them... no trace of Sappho the principal of an academy."[127] Campbell in 1967 judged that Sappho may have "presided over a literary coterie", but that "evidence for a formal appointment as priestess or teacher is hard to find".[128] None of Sappho's own poetry mentions her teaching, and the earliest source to support the idea of Sappho as a teacher comes from Ovid, six centuries after Sappho's lifetime.[129]

So you hate me now, Atthis, and

Turn towards Andromeda.

— Sappho 131, trans. Edward Storer[130]

In the second half of the twentieth century, scholars began to interpret Sappho as involved in the ritual education of girls,[131] for instance as a trainer of choruses of girls.[120] Though not all of her poems can be interpreted in this light, Lardinois argues that this is the most plausible social context to site Sappho in.[132] Another interpretation which became popular in the twentieth century was of Sappho as a priestess of Aphrodite. However, though Sappho wrote hymns, including some dedicated to Aphrodite, there is no evidence that she held a priesthood.[124] More recent scholars have proposed that Sappho was part of a circle of women who took part in symposia, for which she composed and performed poetry, or that she wrote her poetry to be performed at men's symposia. Though her songs were certainly later performed at symposia, there is no external evidence for archaic Greek women's symposia, and even if some of her works were composed for a sympotic context, it is doubtful that the cultic hymns or poems about family would have been.[133]

Despite scholars' best attempts to find one, Yatromanolakis argues that there is no single performance context to which all of Sappho's poems can be attributed.[134] Camillo Neri argues that it is unnecessary to assign all of her poetry to one context, and suggests that she could have composed poetry both in a pedogogic role and as part of a circle of friends.[135]

Sexuality

The word lesbian is an allusion to Sappho, originating from the name of the island of Lesbos, where she was born.[o][136] However, though in modern culture Sappho is seen as a lesbian,[136] she has not always been considered so. In classical Athenian comedy (from the Old Comedy of the fifth century to Menander in the late fourth and early third centuries BC), Sappho was caricatured as a promiscuous heterosexual woman,[137] and the earliest surviving sources to explicitly discuss Sappho's homoeroticism come from the Hellenistic period. The earliest of these is a fragmentary biography written on papyrus in the late third or early second century BC,[138] which states that Sappho was "accused by some of being irregular in her ways and a woman-lover".[139] Denys Page comments that the phrase "by some" implies that even the full corpus of Sappho's poetry did not provide conclusive evidence of whether she described herself as having sex with women.[140] These ancient authors do not appear to have believed that Sappho did, in fact, have sexual relationships with other women, and as late as the 10th century the Suda records that Sappho was "slanderously accused" of having sexual relationships with her "female pupils".[141]

Among modern scholars, Sappho's sexuality is still debated: André Lardinois has described it as the "Great Sappho Question".[142] Early translators of Sappho sometimes heterosexualised her poetry.[143] Ambrose Philips' 1711 translation of the Ode to Aphrodite portrayed the object of Sappho's desire as male, a reading that was followed by virtually every other translator of the poem until the 20th century,[144] while in 1781 Alessandro Verri interpreted fragment 31 as being about Sappho's love for Phaon.[145] Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker argued that Sappho's feelings for other women were "entirely idealistic and non-sensual",[146] while Karl Otfried Müller wrote that fragment 31 described "nothing but a friendly affection":[147] Glenn Most comments that "one wonders what language Sappho would have used to describe her feelings if they had been ones of sexual excitement", if this theory were correct.[147] By 1970, the psychoanalyst George Devereux argued that the same poem contained "proof positive of [Sappho's] lesbianism".[148]

Today, it is generally accepted that Sappho's poetry portrays homoerotic feelings:[149][150] as Sandra Boehringer puts it, her works "clearly celebrate eros between women".[151] Toward the end of the 20th century, though, some scholars began to reject the question of whether Sappho was a lesbian — Glenn Most wrote that Sappho herself "would have had no idea what people mean when they call her nowadays a homosexual",[147] André Lardinois stated that it is "nonsensical" to ask whether Sappho was a lesbian,[152] and Page duBois calls the question a "particularly obfuscating debate".[153] Some scholars argue that although Sappho would not have understood modern conceptions of sexuality, lesbianism has always existed and she was fundamentally a lesbian.[150] Others, influenced by Michel Foucault's work on the history of sexuality, believe that it is incoherent to project the concept of lesbianism onto an ancient figure like Sappho.[150] Melissa Mueller argues that Sappho's poetry can be read as queer even if the question of her lesbianism is undecidable.[154]

Legacy

Ancient reputation

In antiquity, Sappho's poetry was highly admired, and several ancient sources refer to her as the "tenth Muse".[155] The earliest surviving text to do so is a third-century BC epigram by Dioscorides,[156][157] but poems are preserved in the Greek Anthology by Antipater of Sidon[158][159] and attributed to Plato[160][161] on the same theme. She was sometimes referred to as "The Poetess", just as Homer was "The Poet".[162] The scholars of Alexandria included her in the canon of nine lyric poets.[163] According to Aelian, the Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon asked to be taught a song by Sappho "so that I may learn it and then die".[164] This story may well be apocryphal, especially as Ammianus Marcellinus tells a similar story about Socrates and a song of Stesichorus, but it is indicative of how highly Sappho's poetry was considered in the ancient world.[165]

Sappho's poetry also influenced other ancient authors. Plato cites Sappho in his Phaedrus, and Socrates' second speech on love in that dialogue appears to echo Sappho's descriptions of the physical effects of desire in fragment 31.[166] Many Hellenistic poets alluded to or adapted Sappho's works.[167] The Locrian poet Nossis was described by Marilyn B. Skinner as an imitator of Sappho, and Kathryn Gutzwiller argues that Nossis explicitly positioned herself as an inheritor of Sappho's position as a female poet.[168] Several of Theocritus' poems allude to Sappho, including Idyll 28, which imitates both her language and meter.[169] Poems such as Erinna's Distaff and Callimachus' Lock of Berenice are Sapphic in theme, being concerned with separation – Erinna from her childhood friend; the lock of Berenice's hair from Berenice herself.[170]

In the first century BC, the Roman poet Catullus established the themes and metres of Sappho's poetry as a part of Latin literature, adopting the Sapphic stanza, believed in antiquity to have been invented by Sappho,[171] giving his lover in his poetry the name "Lesbia" in reference to Sappho,[172] and adapting and translating Sappho's 31st fragment in his poem 51.[173][174] Fragment 31 is widely referenced in Latin literature: as well as by Catullus, it is alluded to by authors including Lucretius in the De rerum natura, Plautus in Miles Gloriosus, and Virgil in book 12 of the Aeneid.[175] Latin poets also referenced other fragments: the section on Eppia in Juvenal's sixth satire references fragment 16,[176] a poem in Sapphic stanzas from Statius' Silvae may reference the Ode to Aphrodite,[177] and Horace's Ode 3.27 alludes to fragment 94.[178]

Other ancient poets wrote about Sappho's life. She was a popular character in ancient Athenian comedy,[137] and at least six separate comedies called Sappho are known.[179][p] The earliest known ancient comedy to take Sappho as its main subject was the early-fifth or late-fourth century BC Sappho by Ameipsias, though nothing is known of it apart from its name.[182] As these comedies survive only in fragments, it is uncertain exactly how they portrayed Sappho, but she was likely characterised as a promiscuous woman. In Diphilos' play, she was the lover of the poets Anacreon and Hipponax.[183] Sappho was also a favourite subject in the visual arts. She was the most commonly depicted poet on sixth and fifth-century Attic red-figure vase paintings[171] – though unlike male poets such as Anacreon and Alcaeus, in the four surviving vases in which she is identified by an inscription she is never shown singing.[184] She was also shown on coins from Mytilene and Eresos from the first to third centuries AD, and reportedly depicted in a sculpture by Silanion at Syracuse, statues in Pergamon and Constantinople, and a painting by the Hellenistic artist Leon.[185]

From the fourth century BC, ancient works portray Sappho as a tragic heroine, driven to suicide by her unrequited love for Phaon.[141] A fragment of a play by Menander says that Sappho threw herself off of the cliff at Leucas out of her love for him.[186] Ovid's Heroides 15 is written as a letter from Sappho to Phaon, and when it was first rediscovered in the 15th century was thought to be a translation of an authentic letter by Sappho.[187] Sappho's suicide was also depicted in classical art, for instance on the first-century BC Porta Maggiore Basilica in Rome.[186]

While Sappho's poetry was admired in the ancient world, her character was not always so well considered. In the Roman period, critics found her lustful and perhaps even homosexual.[188] Horace called her "mascula Sappho" ("masculine Sappho") in his Epistles, which the later Porphyrio commented was "either because she is famous for her poetry, in which men more often excel, or because she is maligned for having been a tribad".[189] By the third century AD, the difference between Sappho's literary reputation as a poet and her moral reputation as a woman had become so significant that the suggestion that there were in fact two Sapphos began to develop.[190] In his Historical Miscellanies, Aelian wrote that there was "another Sappho, a courtesan, not a poetess".[191]

Modern reception

By the medieval period, Sappho's works had been lost, though she was still quoted in later authors. Her work became more accessible in the 16th century through printed editions of those authors who had quoted her. In 1508 Aldus Manutius printed an edition of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, which contained Sappho 1, the Ode to Aphrodite, and the first printed edition of Longinus' On the Sublime, complete with his quotation of Sappho 31, appeared in 1554. In 1566, the French printer Robert Estienne produced an edition of the Greek lyric poets that contained around 40 fragments attributed to Sappho.[192]

In 1652, the first English translation of a poem by Sappho was published, in John Hall's translation of On the Sublime. In 1681 Anne Le Fèvre's French edition of Sappho made her work even more widely known.[193] Theodor Bergk's 1854 edition became the standard edition of Sappho in the second half of the 19th century;[194] in the first part of the 20th century, the papyrus discoveries of new poems by Sappho led to editions and translations by Edwin Marion Cox and John Maxwell Edmonds, and culminated in the 1955 publication of Edgar Lobel's and Denys Page's Poetarum Lesbiorum Fragmenta.[195]

Like the ancients, modern critics have tended to consider Sappho's poetry "extraordinary".[196] As early as the ninth century, Sappho was referred to as a talented female poet,[171] and in works such as Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus and Christine de Pisan's Book of the City of Ladies she gained a reputation as a learned lady.[197] Even after Sappho's works had been lost, the Sapphic stanza continued to be used in medieval lyric poetry,[171] and with the rediscovery of her work in the Renaissance, she began to increasingly influence European poetry. In the 16th century, members of La Pléiade, a circle of French poets, were influenced by her to experiment with Sapphic stanzas and with writing love-poetry with a first-person female voice.[171]

Thy soul

Grown delicate with satieties,

Atthis.

O Atthis,

I long for thy lips.

I long for thy narrow breasts,

Thou restless, ungathered.

From the Romantic era, Sappho's work – especially her Ode to Aphrodite – has been a key influence of conceptions of what lyric poetry should be.[199] Poets such as Alfred Lord Tennyson in the 19th century, and A. E. Housman in the 20th century, have been influenced by her poetry. Tennyson based poems including "Eleanore" and "Fatima" on Sappho's fragment 31,[200] while three of Housman's works are adaptations of the Midnight Poem, long thought to be by Sappho though the authorship is now disputed.[201] At the beginning of the 20th century, the Imagists – especially Ezra Pound, H. D., and Richard Aldington – were influenced by Sappho's fragments; a number of Pound's poems in his early collection Lustra were adaptations of Sapphic poems, while H. D.'s poetry frequently echoed Sappho stylistically and thematically, and in some cases, such as "Fragment 40", more specifically invoke Sappho's writing.[202]

Western classical composers have also been inspired by Sappho. The story of Sappho and Phaon began to appear in opera in the late 18th century, for example in Simon Mayr's Saffo; in the 19th century Charles Gounod's Sapho and Giovanni Pacini's Saffo portrayed a Sappho involved in political revolts. In the 20th century, Peggy Glanville-Hicks' opera Sappho was based on the play by Lawrence Durrell.[171] Instrumental works inspired by Sappho include Chant sapphique by Camille Saint-Saëns,[171] and the percussion piece Psappha by Iannis Xenakis.[203] Composers have also set Sappho's own poetry to music: for example Xenakis' Aïs, which uses text from fragment 95, and Charaxos, Eos and Tithonos (2014) by Theodore Antoniou, based on the 2014 discoveries.[203]

It was not long after the rediscovery of Sappho that her sexuality once again became the focus of critical attention. In the early 17th century, John Donne wrote "Sapho to Philaenis", returning to the idea of Sappho as a hypersexual lover of women.[204] The modern debate on Sappho's sexuality began in the 19th century, with Welcker publishing, in 1816, an article defending Sappho from charges of prostitution and lesbianism, arguing that she was chaste[171] – a position that was later taken up by Wilamowitz at the end of the 19th and Henry Thornton Wharton at the beginning of the 20th centuries.[205] In the 19th century Sappho was co-opted by Charles Baudelaire in France and later Algernon Charles Swinburne in England for the Decadent Movement. The critic Douglas Bush characterised Swinburne's sadomasochistic Sappho as "one of the daughters of de Sade", the French author known for his violent pornographic books.[206] By the late 19th century, lesbian writers such as Michael Field[q] and Amy Levy became interested in Sappho for her sexuality,[207] and by the turn of the 20th century she was considered a "patron saint of lesbians".[208]

From the beginning of the 19th century, women poets such as Felicia Hemans (The Last Song of Sappho) and Letitia Elizabeth Landon (Sketch the First. Sappho, and in Ideal Likenesses) took Sappho as one of their progenitors. Sappho also began to be regarded as a role model for campaigners for women's rights, beginning with works such as Caroline Norton's The Picture of Sappho.[171] Later in that century, she became a model for the so-called New Woman – independent and educated women who desired social and sexual autonomy –[209] and by the 1960s, the feminist Sappho was – along with the hypersexual, often but not exclusively lesbian Sappho – one of the two most important cultural perceptions of her.[210]

The discoveries of new poems by Sappho in 2004 and 2014 excited both scholarly and media attention.[40] The announcement of the Tithonus poem was the subject of international news coverage, and was described by Marilyn Skinner as "the trouvaille of a lifetime".[80] The publication of the Brothers Poem a decade later saw further news coverage and discussion on social media, while M. L. West described the 2014 discoveries as "the greatest for 92 years".[211]

See also

- Ancient Greek literature

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 7 – papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 5

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1231 – papyrus preserving Sappho fr. 15–30

- Lesbian poetry

Notes

- ^ The fragments of Sappho's poetry are conventionally referred to by fragment number, though some also have one or more common names. The most commonly used numbering system is that of Eva-Maria Voigt, which in most cases matches the older Lobel-Page system. Unless otherwise specified, the numeration in this article is from Diane Rayor and André Lardinois' Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works, which uses Voigt's numeration with some variations to account for the fragments of Sappho discovered since Voigt's edition was published. References to ancient authors commenting on Sappho give both the conventional reference, and the numeration given in Campbell's Greek Lyric I: Sappho and Alcaeus.

- ^ According to the Suda she was from Eresos;[14] most testimonia and some of Sappho's own poetry point to Mytilene.[15]

- ^ Strabo says that she was a contemporary of Alcaeus (born c. 620 BC) and Pittacus (c. 645 BC – c. 570 BC); Athenaeus that she was a contemporary of Alyattes, king of Lydia (c. 610 BC – c. 560 BC). The Suda says that she was active during the 42nd Olympiad (612–608 BC), while Eusebius says that she was famous by the 45th Olympiad (600–599 BC).[17]

- ^ In ancient Greece children were commonly named after a grandparent.[22]

- ^ Two in the Oxyrhynchus biography (P.Oxy. 1800), seven more in the Suda, and one in a scholion on Pindar.[23]

- ^ Given as Sappho's father in the Oxyrhynchus biography, Suda, a scholion on Plato's Phaedrus, and Aelian's Historical Miscellanies, and as Charaxos' father in Herodotus.[7]

- ^ Inscriptions on Attic vase paintings read ΦΣΑΦΟ, ΣΑΦΟ, ΣΑΠΠΩΣ, and ΣΑΦΦΟ; on coins ΨΑΠΦΩ, ΣΑΠΦΩ, and ΣΑΦΦΩ all survive.[26]

- ^ Other sources say that Charaxos' lover was called Doricha, rather than Rhodopis.[32]

- ^ Though similar names including Kerkylos are attested.[39]

- ^ Scholars such as Alexander Dale and Richard Martin have suggested that some of Sappho's surviving fragments may have been considered iambic in genre, even though they were not composed in iambic trimeter, by ancient sources.[49][50]

- ^ Though the word "élite" is used as a shorthand for a particular ideological tradition within Archaic Greek poetic thought, it is highly likely that all Archaic poets in fact were part of the elite, both by birth and wealth.[103]

- ^ M. L. West comments on the translation of this word, "'Loveliness' is an inadequate translation of habrosyne, but I have not found an adequate one. Sappho does not mean 'elegance' or 'luxury'".[108]

- ^ The pektis harp, also known as the plēktron or plectrum, may be the same as the magadis.[116]

- ^ Sappho names both the lyra and chelynna (lit. 'tortoise');[115] both refer to bowl lyres.[117]

- ^ Similarly the adjective sapphic derives from Sappho's name.[136]

- ^ Plays named Sappho by Ameipsias, Amphis, Antiphanes, Diphilos, Ephippus, and Timocles are attested.[180] Two plays titled Phaon, four titled Leukadia, and one Leukadios may also have featured Sappho.[181]

- ^ Michael Field was the shared pseudonym of the poets and lovers Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper.[207]

References

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 2–9.

- ^ Prioux 2020, pp. 234–235.

- ^ duBois 2015, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Kivilo 2021, p. 11.

- ^ a b Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 4.

- ^ Lefkowitz 2012, p. 42.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 1.

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2001, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Hutchinson 2001, p. 140, n.1.

- ^ a b Kivilo 2010, p. 198, n.174.

- ^ Campbell 1982, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Ferrari 2010, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Campbell 1982, p. xi.

- ^ Hutchinson 2001, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Kivilo 2021, p. 13.

- ^ a b Kivilo 2010, p. 175.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 4 n. 65.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Campbell 1982, p. 15, n.1.

- ^ a b Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 2.

- ^ Sappho, frr. 1.20, 65.5, 94.5, 133b

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 98.

- ^ Lidov 2002, pp. 205–6, n.7.

- ^ Campbell 1982, pp. xi, 189.

- ^ Lidov 2002, p. 203.

- ^ Campbell 1982, pp. 15, 187.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, 2.135 = Sappho 254a

- ^ Lardinois 2021, p. 172.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 3.

- ^ a b Hallett 1982, p. 22.

- ^ Hallett 1982, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 309.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2008, Ch.4 n.36.

- ^ a b c Mendelsohn 2015.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, p. 178.

- ^ a b Kivilo 2010, p. 182.

- ^ Ferrari 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, pp. 179–182.

- ^ Lidov 2002, p. 205, n.7.

- ^ Hallett 1979, pp. 448–449; DeJean 1989, pp. 52–53; Walen 1999, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Dale 2011, pp. 47–55.

- ^ Martin 2016, pp. 115–118.

- ^ Campbell 1982, p. xii.

- ^ a b Bierl & Lardinois 2016, p. 3.

- ^ Lardinois 2008, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Bolling 1961, p. 152.

- ^ de Kreij 2015, p. 28.

- ^ a b Winkler 1990, p. 166.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 180, n.4.

- ^ Prauscello 2021, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 181.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 1999, p. 184.

- ^ Lidov 2011.

- ^ Prauscello 2021, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Clayman 2011.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 81–2.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Tzetzes, On the Metres of Pindar 20–22 = T. 61

- ^ duBois 2015, p. 111.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Williamson 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Apuleius, Apologia 9 = T. 48

- ^ Williamson 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Williamson 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Finglass 2021, pp. 232, 239.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 148.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Finglass 2021, p. 237.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 289.

- ^ duBois 2015, p. 114.

- ^ a b Skinner 2011.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 155.

- ^ Finglass 2021, p. 238.

- ^ Aldington & Storer 1919, p. 15.

- ^ Burn 1960, p. 229.

- ^ Thomas 2021, p. 35.

- ^ Battezzato 2021, p. 121.

- ^ duBois 1995, p. 6.

- ^ duBois 1995, p. 7.

- ^ Lardinois 2022, p. 266.

- ^ Budelmann 2019, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Ferrari 2021, p. 107.

- ^ Kurke 2021, p. 95.

- ^ Kurke 2021, p. 94.

- ^ Ferrari 2021, p. 108.

- ^ Kurke 2021, p. 96.

- ^ Kurke 2021, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Campbell 1967, p. 262.

- ^ Zellner 2008, p. 435.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 66.

- ^ Zellner 2008, p. 439.

- ^ Zellner 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Kurke 2007, p. 152.

- ^ Kurke 2007, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Sappho 2.14–16

- ^ Sappho 58.15

- ^ Kurke 2007, p. 150.

- ^ West 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b duBois 1995, pp. 176–7.

- ^ a b Battezzato 2021, p. 129.

- ^ Gordon 2002, p. xii.

- ^ a b c Battezzato 2021, p. 130.

- ^ West 1992, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson & Mathiesen 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Battezzato 2021, p. 131.

- ^ a b Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 3.

- ^ West 1992, p. 50.

- ^ Battezzato 2021, p. 132.

- ^ West 1992, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 216.

- ^ Lardinois 2022, p. 272.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2009, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 310.

- ^ a b Lardinois 2022, p. 273.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 313.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Page 1959, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Campbell 1967, p. 261.

- ^ Parker 1993, pp. 314–316.

- ^ Aldington & Storer 1919, p. 16.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 316.

- ^ Lardinois 2022, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Lardinois 2022, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 218.

- ^ Neri 2021, pp. 18–21.

- ^ a b c Most 1995, p. 15.

- ^ a b Most 1995, p. 17.

- ^ P.Oxy. 1800 fr. 1 = T 1

- ^ Campbell 1982, p. 3.

- ^ Page 1959, p. 142.

- ^ a b Hallett 1979, p. 448.

- ^ Lardinois 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Gubar 1984, p. 44.

- ^ DeJean 1989, p. 319.

- ^ Most 1995, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Most 1995, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Most 1995, p. 27.

- ^ Devereux 1970.

- ^ Klinck 2005, p. 194.

- ^ a b c Mueller 2021, p. 36.

- ^ Boehringer 2014, p. 151.

- ^ Lardinois 2014, p. 30.

- ^ duBois 1995, p. 67.

- ^ Mueller 2021, pp. 47–52.

- ^ Hallett 1979, p. 447.

- ^ AP 7.407 = T 58

- ^ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ^ AP 7.14 = T 27

- ^ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, p. 33.

- ^ AP 9.506 = T 60

- ^ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 312.

- ^ Parker 1993, p. 340.

- ^ Aelian, quoted by Stobaeus, Anthology 3.29.58 = T 10

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2009, p. 221.

- ^ duBois 1995, pp. 85–6.

- ^ Hunter 2021, p. 280.

- ^ Gosetti-Murrayjohn 2006, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Hunter 2021, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Hunter 2021, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schlesier 2015.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Rayor & Lardinois 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Most 1995, p. 30.

- ^ Morgan 2021, p. 292.

- ^ Morgan 2021, p. 290.

- ^ Morgan 2021, p. 292, n. 17.

- ^ Morgan 2021, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Parker 1993, pp. 309–310, n. 2.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2008, Ch. 4.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2008, Ch. 4, n. 57.

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2008, ch. 1.

- ^ Kivilo 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Snyder 1997, p. 114.

- ^ Richter 1965, p. 70.

- ^ a b Hallett 1979, p. 448, n. 3.

- ^ Most 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 72–3.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 73–4.

- ^ Aelian, Historical Miscellanies 12.19 = T 4

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 84.

- ^ Wilson 2012, p. 501.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 229.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 337.

- ^ Hallett 1979, p. 449.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 82–3.

- ^ Pound 1917, p. 55.

- ^ Kurke 2007, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Peterson 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Sanford 1942, pp. 223–4.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 310–312.

- ^ a b Yatromanolakis 2019, § "Early Modern and Modern Reception".

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 85–6.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 295.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 231–2.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2001, p. 261.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 294.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 258–9.

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 359.

- ^ Finglass 2021, pp. 238–239.

Works cited

- The Poems of Anyte of Tegea with Poems and Fragments of Sappho. Translated by Aldington, Richard; Storer, Edward. London: The Egoist. 1919. OCLC 556498375.

- Anderson, Warren (2001). "Sappho". Grove Music Online. Revised by Thomas J. Mathiesen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.24571. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Battezzato, Luigi (2021). "Sappho's Metres and Music". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–134. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André (2016). "Introduction". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André (eds.). The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Boehringer, Sandra (2014). "Female Homoeroticism". In Hubbard, Thomas K. (ed.). A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9572-0.

- Bolling, George Melville (1961). "Textual Notes on the Lesbian Poets". The American Journal of Philology. 82 (2): 151–163. doi:10.2307/292403. JSTOR 292403.

- Budelmann, Felix (2019). Greek Lyric: A Selection. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63387-1.

- Burn, A. R. (1960). The Lyric Age of Greece. New York: St Martin's Press. OCLC 1331549123.

- Campbell, D. A. (1967). Greek Lyric Poetry: A Selection of Early Greek Lyric, Elegiac and Iambic Poetry. London: Macmillan. OCLC 867865631.

- Campbell, D. A., ed. (1982). Greek Lyric 1: Sappho and Alcaeus. Loeb Classical Library No. 142. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99157-6.

- Clayman, Dee (2011). "The New Sappho in a Hellenistic Poetry Book". Classics@. 4. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- Dale, Alexander (2011). "Sapphica". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 106: 47–74. JSTOR 23621995.

- DeJean, Joan (1989). Fictions of Sappho: 1546–1937. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-14135-0.

- de Kreij, Mark (2015). "Transmissions and Textual Variants: Divergent Fragments of Sappho's Songs Examined". In Lardinois, André; Levie, Sophie; Hoeken, Hans; Lüthy, Christoph (eds.). Texts, Transmissions, Receptions: Modern Approaches to Narratives. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-27084-8.

- Devereux, George (1970). "The Nature of Sappho's Seizure in Fr. 31 LP as Evidence of Her Inversion". The Classical Quarterly. 20 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1017/S0009838800044542. JSTOR 637501. PMID 11620360. S2CID 3193720.

- duBois, Page (1995). Sappho Is Burning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-16755-8.

- duBois, Page (2015). Sappho. Understanding Classics. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-784-53361-8.

- Ferrari, Franco (2010). Sappho's Gift: The Poet and Her Community. Translated by Acosta-Hughes, Benjamin; Prauscello, Lucia. Ann Arbor: Michigan Classical Press. ISBN 978-0-9799713-3-4.

- Ferrari, Franco (2021). "Performing Sappho". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Finglass, P. J. (2021). "Sappho on the Papyri". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Gordon, Pamela (2002). "Introduction". Sappho: Poems and Fragments. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-591-8.

- Gosetti-Murrayjohn, Angela (Winter 2006). "Sappho as the Tenth Muse in Hellenistic Epigram". Arethusa. 39 (1): 21–45. doi:10.1353/are.2006.0003. JSTOR 44578087. S2CID 161681219.

- Gubar, Susan (1984). "Sapphistries". Signs. 10 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1086/494113. JSTOR 3174236. S2CID 225088703.

- Hallett, Judith P. (1979). "Sappho and her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality". Signs. 4 (3): 447–464. doi:10.1086/493630. JSTOR 3173393. S2CID 143119907.

- Hallett, Judith P. (1982). "Beloved Cleïs". Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica. 10: 21–31. doi:10.2307/20538708. JSTOR 20538708.

- Hunter, Richard (2021). "Sappho and Hellenistic Poetry". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–289. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Hutchinson, G. O. (2001). Greek Lyric Poetry: A Commentary on Selected Larger Pieces. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924017-3.

- Kivilo, Maarit (2010). Early Greek Poets' Lives: The Shaping of the Tradition. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19328-4.

- Kivilo, Maarit (2021). "Sappho's Lives". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Klinck, Anne L. (2005). "Sleeping in the Bosom of a Tender Companion". Journal of Homosexuality. 49 (3–4): 193–208. doi:10.1300/j082v49n03_07. PMID 16338894. S2CID 35046856.

- Kurke, Leslie V. (2007). "Archaic Greek Poetry". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82200-8.

- Kurke, Leslie V. (2021). "Sappho and Genre". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Lardinois, André (2008). "Someone, I Say, Will Remember Us: Oral Memory in Sappho's Poetry". In Mackay, Anne (ed.). Orality, Literacy, Memory in the Ancient Greek and Roman World. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-47-43384-2.

- Lardinois, André (2014) [1989]. "Lesbian Sappho and Sappho of Lesbos". In Bremmer, Jan (ed.). From Sappho to De Sade: Moments in the History of Sexuality. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-78124-5.

- Lardinois, André (2021). "Sappho's Personal Poetry". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Lardinois, André (2022). "Sappho". In Swift, Laura (ed.). A Companion to Greek Lyric. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-119-12265-4.

- Lefkowitz, Mary R. (2012). The Lives of the Greek Poets (2 ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4214-0464-6.

- Lidov, Joel (2002). "Sappho, Herodotus and the Hetaira". Classical Philology. 97 (3): 203–237. doi:10.1086/449585. JSTOR 1215522. S2CID 161865691.

- Lidov, Joel (2011). "The Meter and Metrical Style of the New Poem". Classics@. 4. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- Martin, Richard P. (2016). "Sappho, Iambist: Abusing the Brother". In Bierl, Anton; Lardinois, André (eds.). The Newest Sappho: P. Sapph. Obbink and P. GC inv. 105, frs.1–4. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31483-2.

- Mendelsohn, Daniel (16 March 2015). "Girl, Interrupted: Who Was Sappho?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- Morgan, Llewelyn (2021). "Sappho at Rome". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 290–302. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Most, Glenn W. (1995). "Reflecting Sappho". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 40: 15–38. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1995.tb00462.x. JSTOR 43646574.

- Mueller, Melissa (2021). "Sappho and Sexuality". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–52. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Neri, Camillo, ed. (2021). Saffo: Testimonianze e Frammenti [Sappho: Testimonies and Fragments] (in Italian). Berlin: de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110735918. ISBN 978-3-11-073591-8. S2CID 239602934.

- Page, D. L. (1959). Sappho and Alcaeus. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 6290898.

- Parker, Holt (1993). "Sappho Schoolmistress". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 123: 309–351. doi:10.2307/284334. JSTOR 284334.

- Peterson, Linda H. (1994). "Sappho and the Making of Tennysonian Lyric". ELH. 61 (1): 121–137. doi:10.1353/elh.1994.0010. JSTOR 2873435. S2CID 162385092.

- Pound, Ezra (1917). Lustra of Ezra Pound with Earlier Poems. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 1440346.

- Prauscello, Lucia (2021). "The Alexandrian Edition of Sappho". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Prioux, Évelyne (2020). "Les Portraits de poétesses, du IVe siecle avant J.-C. à l'époque impériale". In Cusset, C.; Belenfant, P.; Nardone, C.-E. (eds.). Féminités Hellénistiques: Voix, Genre, Représentations. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-4069-7.

- Rayor, Diane; Lardinois, André (2014). Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02359-8.

- Reynolds, Margaret, ed. (2001). The Sappho Companion. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-973861-9.

- Richter, Gisela M. A. (1965). The Portraits of the Greeks. Vol. 1. London: Phaidon Press. OCLC 234106.

- Sanford, Eva Matthews (1942). "Classical Poets in the Work of A. E. Housman". The Classical Journal. 37 (4): 222–224. JSTOR 3291612.

- Schlesier, Renate (2015). "Sappho". Brill's New Pauly Supplements II. Vol. 7: Figures of Antiquity and Their Reception in Art, Literature, and Music. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Skinner, Marilyn B. (2011). "Introduction". Classics@. 4. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Snyder, Jane McIntosh (1997). "Sappho in Attic Vase Painting". In Koloski-Ostrow, Ann Olga; Lyons, Claire L.; Kampen, Natalie Boymel (eds.). Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-60385-5.

- Thomas, Rosalind (2021). "Sappho's Lesbos". In Finglass, P. J.; Kelly, Adrian (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Sappho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-63877-4.

- Walen, Denise A. (1999). "Sappho in the Closet". In Davis, Tracy C.; Donkin, Ellen (eds.). Women and Playwriting in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 233–256. ISBN 978-0-521-65982-6.

- West, Martin Litchfield (1992). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158685-9.

- West, Martin L. (2005). "The New Sappho". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 151: 1–9. JSTOR 20191962.

- Williamson, Margaret (1995). Sappho's Immortal Daughters. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-78912-8.

- Wilson, Penelope (2012). "Women Writers and the Classics". In Hopkins, David; Martindale, Charles (eds.). The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature. Vol. 3 (1660–1790). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921981-0.

- Winkler, John J. (1990). The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90123-9.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (1999). "Alexandrian Sappho Revisited". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 99: 179–195. doi:10.2307/311481. JSTOR 311481.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2008). Sappho in the Making: the Early Reception. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02686-5.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (2009). "Alcaeus and Sappho". In Budelmann, Felix (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-00247-9.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios (27 February 2019) [10 May 2017]. "Sappho". Oxford Bibliographies: Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195389661-0074. ISBN 978-0-19-538966-1. (subscription required)

- Zellner, Harold (Summer 2008). "Sappho's Sparrows". The Classical World. 101 (4): 435–442. doi:10.1353/clw.0.0026. JSTOR 25471966. S2CID 162301196.

Further reading

- Balmer, Josephine (2018). Sappho: Poems and Fragments (2 ed.). Hexham: Bloodaxe Books. ISBN 978-1-78037-457-4.

- Boehringer, Sandra (2021). Female Homosexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome. Translated by Preger, Anna. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-74476-2.

- Carson, Anne (2002). If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41067-3.

- Freeman, Philip (2016). Searching for Sappho: The Lost Songs and World of the First Woman Poet. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24223-2.

- Greene, Ellen, ed. (1996). Reading Sappho. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20603-8.

- Lobel, E.; Page, D. L., eds. (1955). Poetarum Lesbiorum fragmenta. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814137-2.

- Powell, Jim (2019). The Poetry of Sappho. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-093738-6.

- Snyder, Jane McIntosh (1997). Lesbian Desire in the Lyrics of Sappho. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-09994-3.

- Tucker, Thomas George (1914). Sappho. Melbourne: Thomas C. Lothian. OCLC 261327474.

- Voigt, Eva-Maria (1971). Sappho et Alcaeus. Fragmenta. Amsterdam: Polak & van Gennep. OCLC 848526203.

External links

- The Digital Sappho – Texts and Commentary on Sappho's works

- Commentaries on Sappho's fragments, William Annis.

- Fragments of Sappho, translated by Gregory Nagy and Julia Dubnoff

- Sappho, BBC Radio 4, In Our Time.

- Sappho, BBC Radio 4, Great Lives.

- Ancient Greek literature recitations, hosted by the Society for the Oral Reading of Greek and Latin Literature. Including a recording of Sappho 1 by Stephen Daitz.