Trends in LIMS

Contents

| Clostridium tetani | |

|---|---|

| |

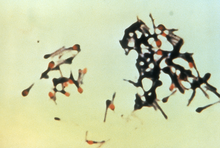

| Clostridium tetani forming spores | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia |

| Order: | Eubacteriales |

| Family: | Clostridiaceae |

| Genus: | Clostridium |

| Species: | C. tetani

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clostridium tetani Flügge, 1881

| |

Clostridium tetani is a common soil bacterium and the causative agent of tetanus. Vegetative cells of Clostridium tetani are usually rod-shaped and up to 2.5 μm long, but they become enlarged and tennis racket- or drumstick-shaped when forming spores. C. tetani spores are extremely hardy and can be found globally in soil or in the gastrointestinal tract of animals. If inoculated into a wound, C. tetani can grow and produce a potent toxin, tetanospasmin, which interferes with motor neurons, causing tetanus. The toxin's action can be prevented with tetanus toxoid vaccines, which are often administered to children worldwide.

Characteristics

Clostridium tetani is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium, typically up to 0.5 μm wide and 2.5 μm long.[1] It is motile by way of various flagella that surround its body.[1] C. tetani cannot grow in the presence of oxygen.[1] It grows best at temperatures ranging from 33 to 37 °C.[1]

Upon exposure to various conditions, C. tetani can shed its flagellums and form a spore.[1] Each cell can form a single spore, generally at one end of the cell, giving the cell a distinctive drumstick shape.[1] C. tetani spores are extremely hardy and are resistant to heat, various antiseptics, and boiling for several minutes.[2] The spores are long-lived and are distributed worldwide in soils as well as in the intestines of various livestock and companion animals.[3]

Evolution

Clostridium tetani is classified within the genus Clostridium, a broad group of over 150 species of Gram-positive bacteria.[3] C. tetani falls within a cluster of nearly 100 species that are more closely related to each other than they are to any other genus.[3] This cluster includes other pathogenic Clostridium species such as C. botulinum and C. perfringens.[3] The closest relative to C. tetani is C. cochlearium.[3] Other Clostridium species can be divided into a number of genetically related groups, many of which are more closely related to members of other genera than they are to C. tetani.[3] Examples of this include the human pathogen C. difficile, which is more closely related to members of genus Peptostreptococcus than to C. tetani.[4]

Role in disease

While C. tetani is frequently benign in the soil or in the intestinal tracts of animals, it can sometimes cause the severe disease tetanus. Disease generally begins with spores entering the body through a wound.[5] In deep wounds, such as those from a puncture or contaminated needle injection the combination of tissue death and limited exposure to surface air can result in a very low-oxygen environment, allowing C. tetani spores to germinate and grow.[2] As C. tetani grows at the wound site, it releases the toxins tetanolysin and tetanospasmin as cells lyse.[1] The function of tetanolysin is unclear, although it may help C. tetani to establish infection within a wound.[6][1] Tetanospasmin ("tetanus toxin") is a potent toxin with an estimated lethal dose less than 2.5 nanograms per kilogram of body weight, and is responsible for the symptoms of tetanus.[6][1] Tetanospasmin spreads via the lymphatic system and bloodstream throughout the body, where it is taken up into various parts of the nervous system.[6] In the nervous system, tetanospasmin acts by blocking the release of the inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid at motor nerve endings.[5] This blockade leads to the widespread activation of motor neurons and spasming of muscles throughout the body.[6] These muscle spasms generally begin at the top of the body and move down, beginning about 8 days after infection with lockjaw, followed by spasms of the abdominal muscles and the limbs.[5][6] Muscle spasms continue for several weeks.[6]

The gene encoding tetanospasmin is found on a plasmid carried by many strains of C. tetani; strains of bacteria lacking the plasmid are unable to produce toxin.[1][5] The function of tetanospasmin in bacterial physiology is unknown.[1]

Treatment and prevention

Clostridium tetani is susceptible to a number of antibiotics, including chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, penicillin G, and tetracycline.[3] However, the usefulness of treating C. tetani infections with antibiotics remains unclear.[1] Instead, tetanus is often treated with tetanus immune globulin to bind up circulating tetanospasmin.[6] Additionally, benzodiazepines or muscle relaxants may be given to reduce the effects of the muscle spasms.[1]

Damage from C. tetani infection is generally prevented by administration of a tetanus vaccine consisting of tetanospasmin inactivated by formaldehyde, called tetanus toxoid.[1] This is made commercially by growing large quantities of C. tetani in fermenters, then purifying the toxin and inactivating in 40% formaldehyde for 4–6 weeks.[1] The toxoid is generally coadministered with diphtheria toxoid and some form of pertussis vaccine as DPT vaccine or DTaP.[6] This is given in several doses spaced out over months or years to elicit an immune response that protects the host from the effects of the toxin.[6]

Research

Clostridium tetani can be grown on various anaerobic growth media such as thioglycolate media, casein hydrolysate media, and blood agar.[1] Cultures grow particularly well on media at a neutral to alkaline pH, supplemented with reducing agents.[1] The genome of a C. tetani strain has been sequenced, containing 2.80 million base pairs with 2,373 protein coding genes.[7]

History

Clinical descriptions of tetanus associated with wounds are found at least as far back as the 4th century BCE, in Hippocrates' Aphorisms.[8] The first clear connection to the soil was in 1884, when Arthur Nicolaier showed that animals injected with soil samples would develop tetanus.[6] In 1889, C. tetani was isolated from a human victim by Kitasato Shibasaburō, who later showed that the organism could produce disease when injected into animals, and that the toxin could be neutralized by specific antibodies. In 1897, Edmond Nocard showed that tetanus antitoxin induced passive immunity in humans, and could be used for prophylaxis and treatment.[6] In World War I, injection of tetanus antiserum from horses was widely used as a prophylaxis against tetanus in wounded soldiers, leading to a dramatic decrease in tetanus cases over the course of the war.[9] The modern method of inactivating tetanus toxin with formaldehyde was developed by Gaston Ramon in the 1920s; this led to the development of the tetanus toxoid vaccine by P. Descombey in 1924, which was widely used to prevent tetanus induced by battle wounds during World War II.[6]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Roper MH, Wassilak SG, Tiwari TS, Orenstein WA (2013). "33 - Tetanus toxoid". Vaccines (6 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 746–772. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-0090-5.00039-2. ISBN 9781455700905.

- ^ a b Pottinger P, Reller B, Ryan KJ, Weissman S (2018). "Chapter 29: Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Other Anaerobes". In Ryan KJ (ed.). Sherris Medical Microbiology (7 ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-259-85980-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rainey FA, Hollen BJ, Small AM (2015). "Clostridium". Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 104–105. doi:10.1002/9781118960608.gbm00619. ISBN 9781118960608.

- ^ Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA (1997). "Chapter 1 - Phylogenetic Relationships". In Rood JI, McClane BA, Songer JG, Titball RW (eds.). The Clostridia: Molecular Biology and Pathogenesis. pp. 3–19. doi:10.1016/B978-012595020-6/50003-6. ISBN 9780125950206.

- ^ a b c d Todar K (2005). "Pathogenic Clostridia, including Botulism and Tetanus". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. p. 3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe C, eds. (2015). "Chapter 21: Tetanus". The Pink Book - Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13 ed.). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. pp. 341–352. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Bruggemann H, Baumer S, Fricke WF, Wiezer A, Liesegang H, Decker I, Herzberg C, Martinez-Arias R, et al. (Feb 2003). "The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease" (PDF). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100 (3): 1316–1321. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.1316B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0335853100. PMC 298770. PMID 12552129. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-17. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ Pearce JM (1996). "Notes on tetanus (lockjaw)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 60 (3): 332. doi:10.1136/jnnp.60.3.332. PMC 1073859. PMID 8609513.

- ^ Wever PC, Bergen L (2012). "Prevention of tetanus during the First World War" (PDF). Medical Humanities. 38 (2): 78–82. doi:10.1136/medhum-2011-010157. hdl:20.500.11755/8e372c60-b6a6-4638-a2ba-664e20b30ad1. PMID 22543225. S2CID 30610331. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2019-09-27.