The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Vedelago, Veneto, Italy |

| Part of | City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii) |

| Reference | 712bis-019 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Website | www |

| Coordinates | 45°42′42.2″N 11°59′28.4″E / 45.711722°N 11.991222°E |

Villa Emo is one of the many creations conceived by Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. It is a patrician villa located in the Veneto region of northern Italy, near the village of Fanzolo di Vedelago, in the Province of Treviso. The patron of this villa was Leonardo Emo and remained in the hands of the Emo family until it was sold in 2004. Since 1996, it has been conserved as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto".[1]

History

Andrea Palladio's architectural fame is considered to have come from the many villas he designed. The building of Villa Emo was the culmination of a long-lasting project of the patrician Emo family of the Republic of Venice to develop its estates at Fanzolo. In 1509, which saw the defeat of Venice in the War of the League of Cambrai, the estate on which the villa was to be built was bought from the Barbarigo family.[2] Leonardo di Giovannia Emo was a well-known Venetian aristocrat. He was born in 1538 and inherited the Fanzolo estate in 1549. This property was dedicated to the agricultural activities from which the family prospered. The Emo family's central interest was at first in the cultivation of their newly acquired land. Not until two generations had passed did Leonardo Emo commission Palladio to build a new villa in Fanzolo.

Historians do not have firm chronology of dates on the design, construction, or the commencement of the new building: the years 1555 or 1558 is estimated to have been when the building was designed, while the construction was thought to have been undertaken between 1558 and 1561. There is no evidence showing that the villa was built by 1549: however, it has been documented to have been built by 1561. The 1560s saw the interior decoration added and the consecration of the chapel in the west barchesse in 1567.[1] The date of completion is put at 1565; a document which attests to the marriage of Leonardo di Alvise with Cornelia Grimani has lasted from that year.[3]

Partial alterations were made to the Villa Emo in 1744 by Francesco Muttoni. Arches within both wings that were close to the central build were sealed off and additional residential areas were created. The ceilings were altered in 1937–1940. The villa and its surrounding estate were purchased in 2004 by an institution and further restorations were made. Since 1996, it has been conserved as part of the World Heritage Site "City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the Veneto".[1]

The villa is at the centre of an extensive area that bears centuriation, or land divisions, and extends northward. The landscape of Fanzolo has a continuous history since Roman times and it has been suggested that the layout of the villa reflects the straight lines of the Roman roads.[2]

Architecture

Villa Emo was a product of Palladio's later period of architecture. It is one of the most accomplished of the Palladian Villas, showing the benefit of 20 years of Palladio's experience in domestic architecture. It has been praised for the simple mathematical relationships expressed in its proportions, both in the elevation and the dimensions of the rooms.

Palladio used mathematics to create the ideal villa. These “harmonic proportions” were a formulation of Palladio's design theory. He thought that the beauty of architecture was not in the use of orders and ornamentation, but in architecture devoid of ornamentation, which could still be a delight to the eye if aesthetically pleasing portions were incorporated.

In 1570, Palladio published a plan of the villa in his treatise I quattro libri dell'architettura. Unlike some of the other plans he included in this work, the one of Villa Emo corresponds nearly exactly to what was built. His classical architecture has stood the test of time and designers still look to Palladio for inspiration.[1]

The layout of the villa and its estate is strategically placed along the pre-existing Roman grid plan. There is a long rectangular axis that runs across the estate in a north–south direction. The agricultural crop fields and tree groves were laid out and arranged along the long axis, as was the villa.[1]

The outer appearance of the Villa Emo is marked by a simple treatment of the body of the building, whose structure is determined by a geometrical rhythm. The construction consists of brick-work with a plaster finish, visible wooden beams seen in the spaces of the piano nobile, and coffered ceilings like that within the loggia. The central structure is an almost square residential area.[4] The living quarters are raised above ground-level, as are all of Palladio's other villas.

Instead of the usual staircase going up to the main front door, the building has a ramp with a gentle slope that is as wide as the pronaos. This reveals the agricultural tradition of this complex. The ramp, an innovation in Palladian villas, was necessary for transportation to the granaries by wheelbarrows loaded with food products and other goods. The wide ramp leads to the loggia which takes the form of a column portico crowned by a gable – a temple front which Palladio applied to secular buildings. As in the case with the Villa Badoer, the loggia does not stand out from the core of the building as an entrance hall, but is retracted into it. The emphasis of simplicity extends to the column order of the loggia, for which Palladio chose the plain Tuscan order.[2] Plain windows embellish the piano nobile as well as the attic.

The central building of the villa is framed by two symmetrical long, lower colonnaded wings, or barchesses, which originally housed agricultural facilities, like granaries, cellars, and other service areas. This was a working villa like Villa Badoer and a number of the other designs by Palladio. Both wings end with tall dovecotes which are structures that house nesting holes for domesticated pigeons. An arcade on the wings face the garden, consisting of columns that have rectangular blocks for the bases and capitols. The west barchesse also contains a chapel. The barchesses merge with the central residence, forming one architectural unit. This typological format of a villa-farm was invented by Palladio and can be found at Villa Barbaro and Villa Baroer.[1]

Palladio emphasises the usefulness of the lay-out in his treatise. He points out that the grain stores and work areas could be reached under cover, which was particularly important. Also, it was necessary for the Villa Emo's size to correspond to the returns obtained by good management. These returns must in fact have been considerable, for the side-wings of the building are unusually long, a visible symbol of prosperity. The Emo family introduced the cultivation of maize on their estate (and the plant, still new in Europe, is depicted in one of Zelotti's frescoes). In contrast to the traditional cultivation of millet, considerably higher returns could be obtained from the maize.[5] It is not clear if the long walk, made of large square paving-stones, which leads to the front of the house, served a practical purpose. It seems to be a fifteenth-century threshing floor.[6] However, Palladio advised that threshing should not be carried out near a house.

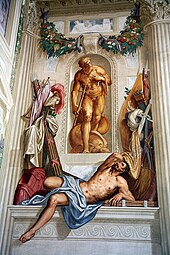

Frescoes

The exterior is simple, bare of any decoration. In contrast, the interior is richly decorated with frescoes by the Veronese painter Giovanni Battista Zelotti, who also worked on Villa Foscari and other Palladian villas. The main series of frescoes in the villa is grouped in an area with scenes featuring Venus, the goddess of love. Zelotti appears to have completed the work on the frescoes by 1566.[1]

In the loggia, the frescoes have representations of Callisto, Jupiter, Jupiter in the Guise of Diana, and Callisto transformed into a Bear by Juno. The Great Room is filled with frescoes that were placed between Corinthian columns that rise from high pedestals. The events in the frescoes concentrate on humanistic ideals and Roman history alluding to marital virtues. Exemplary scenes include Virtue portrayed in a scene from the life of Scipio Africanus. On the left wall is the scene of Scipio returning the girl betrothed to Allucius and the right wall a scene showing The Killing of Virginia. The sides of these frescoes have false niches that consist of monochrome figures: Jupiter holding a torch, Juno and the Peacock, Neptune with the Dolphin, and Cybele with the Lioness. These figures allude to the four natural elements (fire, air, water, earth). Side panels contain enormous prisoners emerging from the false architectural framework. On the south wall of the great hall toward the vestibule is a false broken pediment that appears above a real entrance arch. A fresco of two female figures, Prudence with the Mirror and Peace with an Olive Branch, can be seen. The North wall at the center of the upper part of the building contains the crest of the Emo Family. It is carved and gilt wood, surrounded by trompe-l'œil cornices and festoons.[1]

To the left of the central chamber is the Hall of Hercules. It contains episodes referring mainly to the mythological hero. The intent was to emphasize the victory of virtue and reason over vice. The frescoes are inserted in a framework of false ionic columns. The east wall contains scenes of Hercules embracing Dejanira, Hercules throwing Lica into the sea, and The Fame of Hercules at the center. The west wall is Hercules at the Stake, placed within false arches. On the south wall is a panel above the doorway that depicts a Noli me Tangere (“Touch Me Not”) scene.[1]

To the right of the central chamber is the Hall of Venus. This hall contains episodes that refer to the Goddess of Love. On the west wall within false arches are the scenes of Venus detering Adonis from Hunting and Venus aiding the Wounded Adonis. The east wall fresco shows Venus wounded by Love. On the south wall is a panel above the doorway that shows Penitent St. Jerome.[1]

The Abstinence of Scipio appears frequently in cycles of frescoes for Venetian villas. For example, the Villa la Porto Colleoni in Thiene and Villa Cordellina in Montecchio Maggiore, built nearly 200 years later, also use this image, fostering ideals which, had in the 15th and 16th centuries, resulted from the renewed discussion of the depravity of town life, in contrast to the tranquility, abundance, and freedom of artistic thought associated with rural existence. Hence, another room in the villa is called the Room of the Arts, featuring frescoes with allegories of individual arts, such as astronomy, poetry or music.[7] Within the many frescoes are depictions of different flowers and fruit, including corn, only recently introduced into the Po Valley. Many of the frescoes are presented within false architecture, like columns, arches and architectural framework.[1]

Media

In the 1990s Villa Emo was featured in Guide to Historic Homes: In Search of Palladio,[8] Bob Vila's three-part six-hour production for A&E Network.

The 2002 movie Ripley's Game used the Villa Emo as a location.[9]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k The City of Vicenza and The Palladian Villas in the Veneto: A Guide to the UNESCO Site. Italy: The Unesco Office of the Municipality of Vicenza, the Ministry of Cultural Assets and Activities. 2009. pp. 186–191.

- ^ a b c Wundram (1993), p. 164

- ^ Wundram (1993), p. 165

- ^ Beltramini, Guido (2009). Palladio. Italy. pp. 256–322. ISBN 9781905711246.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wundram (1993), p. 169

- ^ Andrea Palladio Centre Archived June 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (in English and Italian) Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio, accessed September 2008

- ^ Wundram (1993), p. 173

- ^ BobVila.com. "Bob Vila's Guide to Historic Homes: In Search of Palladio".

- ^ "Ripley's Game News" Archived June 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008 05 31

Sources

- The City of Vicena and The Palladian Villas in the Veneto: A Guide to the Unesco Site. Italy: The Unesco Office of the Municipality of the City of Vicenza. 2009. pp. 186–191.

- Wassell, Stephen R. (Fall 2018). "Andrea Palladio (1508-1580)". Nexus Network Journal: 213–222.

- Beltramini, Guido (2008). Palladio. Italy. pp. 100–108, 258–322. ISBN 978-1-905711-24-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Boucher, Bruce (1998) [1994]. Andrea Palladio: The Architect in his Time (revised ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 9780789203007.

- Rybczynski, Witold (2002). The Perfect House: A Journey with Renaissance Master Andrea Palladio. New York: Scribner.

- Wundram, Manfred (1993). Andrea Palladio 1508-1580, Architect between the Renaissance and Baroque. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-0271-9.

External links

- Villa Emo - official site