The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

| Sarbloh Granth ਸਰਬਲੋਹ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ | |

|---|---|

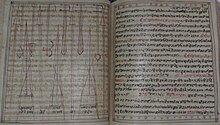

Weapons drawn and inscribed with martial hymns eulogizing them on an illustrated folio of a Sarbloh Granth manuscript | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Author | Guru Gobind Singh (disputed) [1] |

| Language | Sant Bhasha (mainly influenced by Braj) |

| Chapters | 5 |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikh scriptures |

|---|

|

| Guru Granth Sahib |

| Dasam Granth |

| Sarbloh Granth |

| Varan Bhai Gurdas |

The Sarbloh Granth or Sarabloh Granth (Punjabi: ਸਰਬਲੋਹ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ, sarabalōha grantha, literally 'Scripture of Pure Iron'[note 1]),[4] also called Manglacharan Puran[5] or Sri Manglacharan Ji, is a voluminous scripture, composed of more than 6,500 poetic stanzas.[6] It is traditionally attributed as being the work of Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh guru.[7][5] Scholars, on the other hand, attribute the work to after the Guru's death, being authored by an unknown poet.[5][8] The work is mostly revered by the Nihang sect.[9]

History

Traditional narrative

As per the traditions of the Nihang Sikhs, the Sarbloh Granth was written at the Sarbloh Bunga (now called the Langar Sahib) at Takht Abachal Nagar, Hazur Sahib in Nanded, India.[10] They believe the work derives from Sanskrit sutras that were preserved by a group of sadhus, with these sutras ultimately originating from a previous incarnation of Guru Gobind Singh known as rishi Dusht Daman.[10] It is further believed that Banda Singh Bahadur heard the last verses of the work.[10] It is claimed that the Sanskrit sutras the Sarbloh Granth is based on is still kept in a private familial collection.[10]

Authorship

Very little can be ascertained regarding the authorship, compilation, or nature of the contents within the scripture.[11] There is a high degree of controversy among various scholars on the issue of the authorship of the Granth.[12] The following are some of the view points of prominent figures:

- According to Pundit Tara Singh, Sarabloh Granth was composed by Bhai Sukha Singh, a Granthi of Patna.[13][14]

- According to Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha, Sarabloh Granth was not written by Guru Gobind Singh and Khalsa Mahima appeared in it is out of context to the main storyline.[15]

- According to Santa Singh Nihang, Sarabloh Granth was written by Guru Gobind Singh and was completed in Nanded.[16]

- A meeting of Sikh scholars and saints determined that Sarbloh Granth is the writings of Guru Gobind Singh and that the Sarbloh Granth was finalised at Nanded.[17][better source needed]

One narrative claims that the scripture is the result of the writings of the tenth Guru being combined, after his passing in 1708, by his followers.[18] According to Harnam Das Udasi, a Sikh scholar who prepared an annotated edition of the scripture, the text was authored by Guru Gobind Singh.[11] However, Harnam Das Udasi claims that Guru Gobind Singh accepted the work of some poets to form parts of the scripture, just like how Guru Arjan accepted the works written by Bhagats, Bhatts, and Sufi fakirs when he compiled the Adi Granth.[10] However, other analysts date the text to the late 18th-century.[11]

Gurinder Singh Mann argues that the Sarbloh Granth was produced within the courtly setting of Anandpur in the late 17th-century (specifically the 1690's) by various courtly poets (most of whose names are not known).[11]

"In my view, the Dasam Granth and Sri Sarab Loh Granth are markers of the aura of royalty that the Sikhs attempted to create at Anandpur. The poets gathered there drew upon a shared reservoir of themes, literary forms, metaphors and images to create their songs. With the emergence of Sikh power, some poets who were resident in the broader region moved to Anandpur. A cursory look at their compositions shows the structural changes that had to be made to adjust these works to the needs of the new situation. The statements at the closing of the two longest compositions, the Krishan Avatar and Ram Avatar, carry thundering assertions of the futility of, worshipping Krishan and Ram. I can only explain them as addenda having been required to make these texts presentable at Anandpur."

— Gurinder Singh Mann, Sources for the Study of Guru Gobind Singh's Life and Times, page 256

The scripture is largely revered by the Nihang sect of Sikhs with many non-Nihang Sikhs rejecting it as an authentic work of the tenth guru, especially amongst Sikh academics.[19][20][21][9] According to Gurmukh Singh, the authenticity of the work is rejected on the grounds of its writing style and mastery of poetry not matching up with Guru Gobind Singh's Dasam Granth work.[14] Also, the text makes mention of a work composed in 1719, much after the death of the Guru.[14] W. H. McLeod dates the work to the late 18th century and believes it was authored by an unknown poet and was mistakenly attributed to the tenth Guru.[8]

Manuscripts

Gurinder Singh Mann claims to have come across a manuscript of the scripture that dates to the late 17th-century, specifically the year 1698.[note 2][11] Additionally, Harnam Das Udasi claims to have encountered a manuscript of the scripture that bears the same date for its year of compilation (1698), while he was examining twenty-four extant manuscripts of the text as part of his research activities to produce an annotated edition of the scripture.[11] In these two early manuscripts of the scripture, the first contains the Bachittar Natak Granth on folios 1 to 350 and then continues with the text of the Sarbloh Granth-proper for the remainder of the folios (folios 351 to 702).[11] For the second early manuscript, it only contains the text of the Sarbloh Granth-proper and there is no inclusion of external texts, unlike the other manuscript.[11] However, the second manuscript's pagination begins with folio 351 and ends with folio 747.[11] All together, three early manuscripts of the scripture bear their year 1698.[11] However, it can be argued that these manuscripts were a later copy of an original from 1698 and this date was copied as well from the original in all three later copies by their respective scribes.[11] Many early manuscripts of the scripture contain an inscription by Gurdas Singh which goes as: "Sambat satra sai bhae barakh satvanja jan. Gurdas Singh puran kio sri mukh granth parmanh."[11] An inscription sourced from this scripture can be found in the seal of Banda Singh Bahadur and on coins minted during the reign of later Sikh polities.[11]

According to Kamalroop Singh, there are a number of early manuscripts of the Sarbloh Granth dating to the late 17th and 18th centuries.[10] Kamaroop Singh believes the manuscriptural evidence points to the year 1698 in Anandpur Sahib as when the majority of the work of the Sarbloh Granth was commenced, being finalized in 1708 at Hazur Sahib.[10]

List of earliest manuscripts

Kamalroop Singh lists manuscripts of the Sarbloh Granth with a 1698 CE (1755 VS) colophon as follows:[10]

- Nabho Katho vālī bīṛ at Hazur Sahib, which bears a colophon of 1698.[10] This manuscript was studied by Harnam Singh Udasi.[10]

- A manuscript kept at the Chhauṇī (cantonment) of Mata Sahib Kaur[10]

- A manuscript is preserved by the Udasi Sampradāvāṅ at Bhankandi[10]

- A manuscript held at Muktsar Sahib[10]

Present

The 2021 Singhu border incident involved the desecration of a manuscript of the Sarbloh Granth, which angered a group of Nihangs who killed the perpetrator of the sacrilege.[22]

Description

Role

The Sarabloh Granth is a separate religious text from the Guru Granth Sahib and Dasam Granth, and no hymn or composition of this granth is used in daily Sikh liturgy or Amrit Sanchar. Nihang Sikhs hold the scripture in reverence, as they attribute its authorship to Guru Gobind Singh.[11] Nihang Sikhs place the Sarbloh Granth on the left-side of the Guru Granth Sahib (with the Dasam Granth being placed on the right-side) in their public worship arrangement.[11]

Structure and contents

Sarbloh Granth is separated into 5 chapters known as adhiyas.[23][5] The scripture itself is 1665 pages in-length total and comprises three volumes.[24] A printed version released by Santa Singh is 862 pages in-length.[14] At the end of the five chapters is an appendment containing information on Vishnu's incarnations.[25]

The first chapter contains praise and invocations to various devis (goddesses).[14] The second chapter covers Vishnu as an incarnation of the supreme God.[14] Chapter five, which is also the longest chapter,[5] concludes that the various gods and goddesses mentioned formerly are incarnations of Sarabloh (literally meaning "all-iron"), which itself is an incarnation of Mahakal, a term used by Guru Gobind Singh to refer to the all-mighty divine being.[14]

Chapter One

The first chapter, or Pahila Adhiya (Gurmukhi: ਪਹਿਲਾ ਅਧਯਾਯ, romanized: Pahilā adhayāya, lit. 'First chapter'), contains praises toward Maha Maya and Maha Kala.[25] The Indic demi-gods (devte) lose a battle to demons, and request the devi, Chandi, to assist them.[25] Chandi then defeats the demoniacal army and their leader, Bhimnad.[25]

Chapter Two

In the second chapter, or Duja Adhiya (Gurmukhi: ਦੂਜਾ ਅਧਯਾਯ, romanized: Dūjā adhayāya, lit. 'Second chapter'), the wife of the defeated Bhimnad commits sati.[25] Bhimnad's brother, Brijnad, prepares for revenge by starting another war against the demi-gods.[25] The deity Indra writes letters to all the demi-gods asking for their help in the upcoming war.[25]

Chapter Three

In the third chapter, or Tija Adhiya (Gurmukhi: ਤੀਜਾ ਅਧਯਾਯ, romanized: Tījā adhayāya, lit. 'Third chapter'), the demons are winning against the demi-gods, thus Vishnu sends Narada to serve as their representative to Brijnad.[25] However, Brijnad would not negotiate and hostilities resumed.[25] In the beginning of the unsuing battle, eleven armies of Brijnad that were on-foot were destroyed.[25]

Chapter Four

In the fourth chapter, or Cautha Adhiya (Gurmukhi: ਚੌਥਾ ਅਧਯਾਯ, romanized: Cauthā adhayāya, lit. 'Fourth chapter'), a great battle is being waged.[25] Vishnu gives amrit (ambrosial nectar) to the demi-gods, reinvigorating them.[25] Indra captures the demons, yet Brijnad gains the upper-hand and attains victory in the battle, with Indra being captured by the demonic force.[25]

Chapter Five

In the fifth chapter, or Panjva Adhiya (Gurmukhi: ਪੰਜਵਾ ਅਧਯਾਯ, romanized: Pajavā adhayāya, lit. 'Fifth chapter'), the aftermath of the demi-gods losing to the demons results in the demi-gods appealing to Akal Purakh for divine help.[25] Thus, Akal Purakh incarnates as Sarbloh Avtar ("all-iron incarnation").[25] The demi-god Ganesha is appointed as Sarbloh Avtar's ambassador to Brijnad.[25] However, Brijnad does not listen to Ganesha and wages another war.[25] The demi-gods team-up with Sarbloh Avtar against the Indic demons.[25] The demons and Brijnad are then "immersed in bliss" after attainting darshan (auspicious sight) of Sarbloh Avtar, with Brijnad praising Sarbloh Avtar.[25] Sarbloh Avtar then takes on a terrifying form and annihilates all of the demons, including Brijnad in a final battle.[25]

Appendment on Vishnu's Avatars

After the conclusion of the fifth chapter, there is another section narrating incarnations of Vishnu.[25] A list of the avatars of Vishnu discussed in this part includes the following:[25]

- Mach Avtar – fish incarnation[25]

- Kach Avtar – tortoise incarnation[25]

- Barhā Avtar – wild-boar incarnation[25]

- Nar Singh Avtar – half-man and half-lion incarnation[25]

- Purshraam Avtar – Parashurama[25]

- Ram Avtar, called 'Bīj Ramaein' – Rama[25]

- Krishan Avtar, called "Dasam Sakand" (tenth chapter of Bhagvad Purana) – Krishna[25]

Themes

The scripture deals largely on the art of warfare from a Sikh perspective.[26] Within the scripture is contained the Das grāhī-Das tiāgī (ten virtues to hold – ten vices to renounce) for the Khalsa, as narrated by Guru Gobind Singh.[26] All the names employed by Guru Gobind Singh in the Jaap Sahib to describe the divine find mention in the Sarbloh Granth.[10] The scripture promotes the idea that the Waheguru mantar (mantra) is the only one capable of shedding haumai (ego) if chanted.[27][10]

Indic mythological wars

The work contains stories related to Indian mythology, specifically the battles between gods and goddesses against demonic forces of evil.[28] The plot of the book is very similar to the Chandi Charitar stories found within the Dasam Granth.[14] Some Indic deities mentioned in the composition are Lakshmi, Bhavani, Durga, Jvala, Kali (Kalika), Chandi, Hari, Gopal, Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, and Indra.[14] Indic demons, such as Bhiminad and Viryanad, are also involved in the text's story-line.[14] The text also narrates the story of an incarnation of the divine known as 'Sarab Loh' ("all-steel") who defeats the king of the demons, Brijnad.[9] According to Gurinder Singh Mann, the scripture's main theme is the annihilation of demons and evil by an incarnation of the divine known as 'Mahakal' or 'Shiva', he links this theme to a similar one that is presented in the Bachittar Natak Granth, which is part of the Dasam Granth collection of texts.[11]

Khalsa Panth

The scripture discusses the Sikh concept of the Khalsa in-depth and in-detail.[11] The text iterates that the Khalsa Panth is the form of Guru Gobind Singh himself and there is no difference between the Khalsa and the Guru.[29][30] The text states that the Khalsa was not created by the Guru out of any rage but rather it was created as the image of the Guru, for balancing reasons, and for the pleasure of the divine.[31] Furthermore, the concept of "Khalsa Raj" ('Khalsa-rule') is presented in the text.[11] Furthermore, the text presents a concise history of the ten human gurus of Sikhism.[11] The Sarbloh Granth narrates that the guruship was passed by Guru Gobind Singh not only on the Guru Granth Sahib, but also the Guru Khalsa Panth.[10] It also goes over the purpose, duties, and responsibilities of the Khalsa Panth, describing the Khalsa as an "army of God".[32] The scripture further states the qualities that members of the Khalsa must possess, such as high moral standards, fervently spiritual, and heroic.[33] According to Trilochan Singh, all of the 5Ks are mentioned in the text, however Jaswant Singh Neki states only three of them are mentioned.[34]

According to Hazura Singh in his commentary on the scripture, the Khalsa is the liberated form of Nirankar (Prāpati Niraṅkarī sivrūp mahānaṅ), not of the Indic deity Shiva, as some Sanatanist revivalists interpret.[10]

Khalsa Mahima within the Sarbloh Granth

Khalsa Mahima is present in this granth.[35][36][37][self-published source] The Khalsa Mahima is a short-hymn by Guru Gobind Singh.[36]

"The Khalsa is exactly like me, I ever abide in the Khalsa : The Khalsa is my body and soul, The Khalsa is the life of my life"

— Guru Gobind Singh (claimed), Sarbloh Granth, page 531[38]

In this composition, the Guru states that only by the Khalsa keeping its distinct identity can it be successful with his blessing but this blessing would be revoked if the Khalsa loses its unique identity, psyche, and separation from the rest of humanity.[38][39]

A translation of the verses is as follows:[10]

| Sarbloh Granth | |

|---|---|

Ātam ras jo jānahī so hai Khālsā dev. Prabh mai mo mai tās mai raṅchak nāhin bhev. |

Khalsa is the one who experience the bliss of the Super-Soul. There is no difference between God, me (Guru Gobind Singh) and him. |

| —Guru Gobind SIngh | —Kamalroop Singh |

Language

The work is primarily in Braj with influences of other languages as well, making it challenging for readers to comprehend.[5]

Commentary

There is only one complete commentary and exegesis of this granth available, as it is still in research and remains little studied by academic circles so-far.[16][8] The existing commentary was published by Santa Singh of the Budha Dal, an organization of Nihangs.[40][36] Another commentary of the work by Giani Naurang Singh is also extant.[41] An annotated edition (ṭīkā; commentary) of the Sarbloh Granth was produced by Harnam Das Udasi in the late 1980's under the title Sri Sarab Loh Granth Sahib Ji, however its circulation has been restricted.[11] In 1925, an exegesis of the Sarbloh Granth was written by Akali Hazura Singh, then head-granthi of Takht Hazur Sahib (with its foreword written by Akali Kaur Singh).[10] Jathedar Joginder Singh 'Muni' wrote a description of the traditional exegesis (kathā) of the Sarbloh Granth at Hazur Sahib in his work Hazūrī Maryādā Prabodh.[10]

Printing

In 1925, Akali Kaur Singh wrote that there were only around ten manuscripts of the Sarbloh Granth scattered in private collections across India.[10] He urged that a wealthy or royal Sikh should take up the cause of printing the scripture.[10] The mass-printing of the scripture was finally printed undertaken by Santa Singh of the Budha Dal.[10]

Printing of the Sarbloh Granth is carried out by the Chatar Singh Jiwan Singh printing house based in Amritsar for distribution to Nihang-operated gurdwaras.[11] The standard, printed edition contains 1216 pages.[11]

Translation

A full translation to English of the entire Sarbloh Granth has not been done.[25] Translations of select verses can be found on Manglacharan.com.[25]

See also

Notes

- ^ The name 'Sarbloh Granth' can also be translated as meaning "book of all-iron", "all-sword book", or "scripture of wrought iron".[2][3]

- ^ The manuscript bears a recorded Indic date of Samat 1755, miti Bisakh sudi 5 (corresponding to the year 1698 in the Gregorian calendar) as their date of writing, on folios 1 and 2b.

References

- ^ Debating the Dasam Granth. Religion in Translation. American Academy of Religion. 2011. ISBN 978-0199755066.

- ^ Nihang, Nidar Singh (2008). In the master's presence : the Sikhs of Hazoor Sahib. London: Kashi House. p. 33. ISBN 9780956016805.

- ^ Hinnells, John; King, Richard (2007). Religion and Violence in South Asia: Theory and Practice. Routledge. pp. 124–25. ISBN 9781134192199.

- ^ Nabha, Kahn Singh. "ਸਰਬਲੋਹ". Gur Shabad Ratnakar Mahankosh (in Punjabi). Sudarshan Press.

ਸੰ. ਸਰ੍ਵਲੋਹ. ਵਿ- ਸਾਰਾ ਲੋਹੇ ਦਾ

- ^ a b c d e f Mukherjee, Sujit (1998). A dictionary of Indian literature. Vol. 1. Hyderabad: Orient Longman. p. 351. ISBN 81-250-1453-5. OCLC 42718918.

- ^ Mann, JaGurinder Singh nak (1 March 2007). El sijismo. Ediciones Akal. p. 76.

- ^ Singh, Ganda (1951). Patiala and East Panjab States Union: Historical Background. Patiala archives publication. Archives Department, Government of the Patiala and E.P.S. Union. p. 22.

- ^ a b c McLeod, W. H. (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. W. H. McLeod. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6. OCLC 435778610.

- ^ a b c Singh, Pashaura; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2023). The Sikh World. Routledge Worlds. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429848384.

The Nihangs' focus on the traditions of Guru Gobind Singh carry over to his writings as well. They hold the Guru's Dasam Granth in the same regard as Guru Granth Sahib and draw inspiration from its vividly heroic stories. Additionally, Nihangs hold the Sarab Loh Granth in equal esteem. The Sarab Loh Granth is attributed to Guru Gobind Singh and narrates more stories about the conflict between moral gods and evil demons. The drawn-out conflict comes to a head with god taking the incarnate form known as Sarab Loh (all-steel) who was able to overwhelm Brijnad, the demon king, with its martial prowess. The purity of steel, its resolve and durability, all serve as analogies for Akal Purakh's righteousness to which the Nihangs' aspire. Their devotion to the all-steel incarnation is demonstrated via the many steel weapons with which they train and adorn themselves, as well as through their insistence on even their cookware and utensils being made of steel.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Singh, Hazura; Singh, Partap; Singh, Sundar (2012) [1925]. "Foreword". In Singh, Kaur; Singh, Kamalroop (eds.). Loh Prakāsh (PDF). Amritsar.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mann, Gurinder Singh (2008). "Sources for the Study of Guru Gobind Singh's Life and Times" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 15 (1–2): 254–58, 275, 279–281 – via Global Institute for Sikh Studies.

- ^ Sikhs across borders : transnational practices of European Sikhs. Knut A. Jacobsen, Kristina Myrvold. London: Bloomsbury. 2012. pp. 128–29. ISBN 978-1-4411-7087-3. OCLC 820011179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Nabha, Kahn Singh. "ਸਰਬਲੋਹ". Gur Shabad Ratnakar Mahankosh (in Punjabi). Sudarshan Press.

ਪੰਡਿਤ ਤਾਰਾ ਸਿੰਘ ਜੀ ਦੀ ਖੋਜ ਅਨੁਸਾਰ ਸਰਬਲੋਹ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਭਾਈ ਸੁੱਖਾ ਸਿੰਘ ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਹੈ, ਜੋ ਪਟਨੇ ਸਾਹਿਬ ਦਾ ਗ੍ਰੰਥੀ ਸੀ. ਉਸ ਨੇ ਪ੍ਰਗਟ ਕੀਤਾ ਕਿ ਮੈਨੂੰ ਇਹ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਜਗੰਨਾਥ ਦੀ ਝਾੜੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਰਹਿਣ ਵਾਲੇ ਇੱਕ ਅਵਧੂਤ ਉਦਾਸੀ ਤੋਂ ਮਿਲਿਆ ਹੈ, ਜੋ ਕਲਗੀਧਰ ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਹੈ

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Singh, Gurmukh (1992–1998). Singh, Harbans (ed.). The encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 4. Patiala: Punjabi University. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-8364-2883-8. OCLC 29703420.

- ^ Nabha, Kahn Singh. "ਸਰਬਲੋਹ". Gur Shabad Ratnakar Mahankosh (in Punjabi). Sudarshan Press.

ਅਸੀਂ ਭੀ ਸਰਬਲੋਹ ਨੂੰ ਦਸ਼ਮੇਸ਼ ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਮੰਨਣ ਲਈ ਤਿਆਰ ਨਹੀਂ, ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਇਸ ਵਿੱਚ ਰੂਪਦੀਪ ਭਾਸ ਪਿੰਗਲ ਦਾ ਜਿਕਰ ਆਇਆ ਹੈ. ਰੂਪਦੀਪ ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਸੰਮਤ ੧੭੭੬ ਵਿੱਚ ਹੋਈ ਹੈ, ਅਤੇ ਕਲਗੀਧਰ ਸੰਮਤ ੧੭੬੫ ਵਿੱਚ ਜੋਤੀਜੋਤਿ ਸਮਾਏ ਹਨ, ਅਤੇ ਜੇ ਇਹ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਅਮ੍ਰਿਤ ਸੰਸਕਾਰ ਤੋਂ ਪਹਿਲਾ ਹੈ, ਤਦ ਖਾਲਸੇ ਦਾ ਪ੍ਰਸੰਗ ਅਤੇ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਪੰਥ ਨੂੰ ਗੁਰੁਤਾ ਦਾ ਜਿਕਰ ਕਿਸ ਤਰਾਂ ਆ ਸਕਦਾ ਹੈ? ਜੇ ਅਮ੍ਰਿਤਸੰਸਕਾਰ ਤੋਂ ਪਿੱਛੋਂ ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਹੈ, ਤਦ ਦਾਸ ਗੋਬਿੰਦ, ਸ਼ਾਹ ਗੋਬਿੰਦ ਆਦਿਕ ਨਾਮ ਕਿਉਂ? ਸਰਬਲੋਹ ਵਿੱਚ ਬਿਨਾ ਹੀ ਪ੍ਰਕਰਣ ਖਾਲਸਾ- ਧਰਮ ਸੰਬੰਧੀ ਭੀ ਕਈ ਲੇਖ ਆਏ ਹਨ.

- ^ a b Singh, Dayal. Sarabloh Granth Steek. Buddha Dal Panjvaan Takht Printing Press, Bagheechi Baba Bamba Singh Ji, Lower Mall Road, Patiala. p. Intro-ਠ.

- ^ Santa, Singh. Sarbloh Granth Steek (in Punjabi). Budha Dal Printing Press. pp. ਖ.

- ^ Sikhs in Ontario. Judith Bali. Toronto, Ont.: Ontario Council of Sikhs. 1993. p. 72. ISBN 0-9695994-5-5. OCLC 32458938.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rinehart, Robin (2011). Debating the Dasam Granth. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-975506-6. OCLC 606234922.

A text called the Sarabloh Granth, revered by Nihang Sikhs, which narrates some of the same events as Chandi Charitra, has been attributed to Guru Gobind Singh, though most Sikh scholars do not believe he was in fact the author (see Gurmukh Singh 1998a).

- ^ Journal of Sikh Studies. Vol. 38. Guru Nanak University - Department of Guru Nanak Studies. 2014.

As for the Sarabloh Granth, only the Nihangs, a sect among the Sikhs, accept it as the authentic work of the Guru while the Sikh scholarship has universally rejected it.

- ^ The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies. Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech. Oxford. 2016. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. OCLC 874522334.

Outside the Dasam Granth, numerous other writings of similar character are also associated with Guru Gobind Singh, but of these only the large Sarabloh Granth continus to enjoy a canonical status which is restricted to the Nihang Sikhs.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ AGRARIAN REFORM AND FARMER RESISTANCE IN PUNJAB mobilisation and. Shinder S. Thandi. [S.l.]: ROUTLEDGE. 2022. ISBN 978-1-000-81630-3. OCLC 1349274680.

In yet another incident, reiterating the peaceful nature of the farmers' protest, SKM condemned the barbaric killing of a farm labourer, Lakhbir Singh from Cheema Khurd village in Tarn Taran district of Punjab, on October 15, 2021, by a group of Nihangs (a Sikh order, distinguished by their blue robes and traditional weapons) at a farmers' protest site at Kundli on the Delhi-Haryana border. The SKM disassociated itself from them (Shaurya, 2021). Lakhbir Singh had reached the protest site at the Delhi border a week earlier before the unfortunate incident and was staying with a group of Nihangs who allegedly found him desecrating the Sarbloh Granth (sacred scripture) and consequently chopped off his left wrist and a foot, and broke his legs (Team TOL, 2021; The Quint, 2021).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Singh, Santa. Sarbloh Granth Steek (in Punjabi). Budha Dal Printing Press. pp. Introduction 1.

- ^ Singh, Jagjit (1988). In the Caravan of Revolution: Another Perspective View of the Sikh Revolution. Lokgeet Parkashan. p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Singh, Jvala. "Sarbloh Guru Granth Sahib - Sarbloh". Manglacharan. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b Nihang, Nidar Singh (2008). In the master's presence : the Sikhs of Hazoor Sahib. London: Kashi House. p. 33. ISBN 9780956016805.

- ^ Singha, H. S. (2000). The encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 entries). New Delhi: Hemkunt Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 81-7010-301-0. OCLC 243621542.

To wean the followers away from Hindu system of incantations, Sikhism advised them to use 'Waheguru' as the only incantation. 'Waheguru is the only incantation repeating which one sheds one's ego.' Waheguru gurmantar hai jap haumai kho-ai (Vars of Gurdas). Sarbloh Granth also reinforces the same idea: 'Sar mantar charon ka char Waheguru mantar nirdhar.'

- ^ Niraṅkārī, Māna Siṅgha (2008). Sikhism, a perspective. Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry. Chandigarh: Unistar Books. p. 119. ISBN 978-81-7142-621-8. OCLC 289070938.

- ^ Singh, Jagraj (2009). A complete guide to Sikhism. Chandigarh, India: Unistar Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-7142-754-3. OCLC 319683249.

- ^ Gandhi, Surjit Singh (2007). History of Sikh gurus retold. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 800–801. ISBN 978-81-269-0859-2. OCLC 190873070.

- ^ Guranāma Kaura (2013). Studies in Sikhism : its institutions and its scripture in global context. Chandigarh. p. 43. ISBN 978-93-5113-018-5. OCLC 840597999.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Singh, Kharak (2004). Guru Granth-Guru Panth. Chandigarh, India: Institute of Sikh Studies. p. 21.

- ^ The encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Vol. 2. Harbans Singh. Patiala: Punjabi University. 1992–1998. p. 474. ISBN 0-8364-2883-8. OCLC 29703420.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Murphy, Anne (2012). The materiality of the past : history and representation in Sikh tradition. New York. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-991627-6. OCLC 864902695.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ McLeod, W. H. (2003). Sikhs of the Khalsa : a history of the Khalsa rahit. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 138, 325, 431. ISBN 0-19-565916-3. OCLC 51545471.

- ^ a b c Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur (2005). The birth of the Khalsa : a feminist re-memory of Sikh identity. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. xxiv. ISBN 1-4237-4852-2. OCLC 63161582.

- ^ Singh, Janak (22 July 2010). World Religions and the New Era of Science. Xlibris Corporation.

- ^ a b Dhanoa, Surain Singh (2005). Raj Karega Khalsa: Articles on Sikh Religion and Politics - A Gurbani Perspective. Sanbun Publishers. p. 76.

- ^ Preetam, Singh (2003). Baisakhi of the Khalsa Panth. Hemkunt Press. p. 33. ISBN 9788170103271.

- ^ Fenech, Louis E. (2021). "Notes". The Cherished Five in Sikh history. New York. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-19-753287-4. OCLC 1157751641.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Malhotra, Anshu; Mir, Farina (2012). Punjab Reconsidered: History, Culture, and Practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199088775.