The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

A hand plane is a tool for shaping wood using muscle power to force the cutting blade over the wood surface. Some rotary power planers are motorized power tools used for the same types of larger tasks, but are unsuitable for fine-scale planing, where a miniature hand plane is used.

Generally, all planes are used to flatten, reduce the thickness of, and impart a smooth surface to a rough piece of lumber or timber. Planing is also used to produce horizontal, vertical, or inclined flat surfaces on workpieces usually too large for shaping, where the integrity of the whole requires the same smooth surface. Special types of planes are designed to cut joints or decorative mouldings.

Hand planes are generally the combination of a cutting edge, such as a sharpened metal plate, attached to a firm body, that when moved over a wood surface, take up relatively uniform shavings, by nature of the body riding on the 'high spots' in the wood, and also by providing a relatively constant angle to the cutting edge, render the planed surface very smooth. A cutter that extends below the bottom surface, or sole, of the plane slices off shavings of wood. A large, flat sole on a plane guides the cutter to remove only the highest parts of an imperfect surface, until, after several passes, the surface is flat and smooth. When used for flattening, bench planes with longer soles are preferred for boards with longer longitudinal dimensions. A longer sole registers against a greater portion of the board's face or edge surface which leads to a more consistently flat surface or straighter edge. Conversely, using a smaller plane allows for more localized low or high spots to remain.

Though most planes are pushed across a piece of wood, holding it with one or both hands, Japanese planes are pulled toward the body, not pushed away.

Woodworking machinery that perform a similar function as hand planes include the jointer and the thickness planer, also called a thicknesser; the job these specialty power tools can still be done by hand planers and skilled manual labor as it was for many centuries. When rough lumber is reduced to dimensional lumber, a large electric motor or internal combustion engine will drive a thickness planer that removes a certain percentage of excess wood to create a uniform, smooth surface on all four sides of the board and in specialty woods, may also plane the cut edges.

History

Hand planes are ancient, originating thousands of years ago. Early planes were made from wood with a rectangular slot or mortise cut across the center of the body. The cutting blade or iron was held in place with a wooden wedge. The wedge was tapped into the mortise and adjusted with a small mallet, a piece of scrap wood or with the heel of the user's hand. Planes of this type have been found in excavations of old sites as well as drawings of woodworking from medieval Europe and Asia. The earliest known examples of the woodworking plane have been found in Pompeii, although other Roman examples have been unearthed in Britain and Germany. The Roman planes resemble modern planes in essential function, most having iron wrapping a wooden core top, bottom, front and rear, and an iron blade secured with a wedge. One example found in Cologne has a body made entirely of bronze without a wooden core.[1] A Roman plane iron used for cutting moldings was found in Newstead, England.[2] Histories prior to these examples are not clear, but furniture pieces and other woodwork found in Egyptian tombs show surfaces carefully smoothed with some manner of cutting edge or scraping tool. There are suggestions that the earliest planes were simply wooden blocks fastened to the soles of adzes to effect greater control of the cutting action.

In the mid-1860s, Leonard Bailey began producing a line of cast iron-bodied hand planes, the patents for which were later purchased by Stanley Rule & Level, now Stanley Black & Decker. The original Bailey designs were further evolved and added to by Justus Traut and others at Stanley Rule & Level. The Bailey and Bedrock designs became the basis for most modern metal hand plane designs manufactured today. The Bailey design is still manufactured by Stanley Black & Decker.[citation needed]

In 1918 an air-powered handheld planing tool was developed to reduce shipbuilding labor during World War I. The air-driven cutter spun at 8,000–15,000 rpm and allowed one man to do the planing work of up to fifteen men who used manual tools.[3]

Modern hand planes are made from wood, ductile iron or bronze which produces a tool that is heavier and will not rust.

Parts

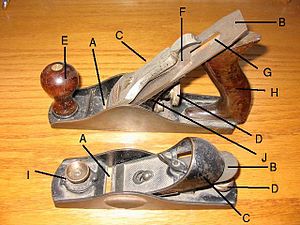

The standard components of a hand plane include:

- mouth: an opening in the sole of the plane through which the blade extends, and through which wood shavings rise.

- iron: a steel blade which cuts the wood.

- lever cap: secures the cap iron and iron firmly to the frog.

- depth adjustment knob: controls the cutting depth of the iron.

- knob: allows a second hand to guide the plane.

- cap iron or chipbreaker: reinforces the iron and curls and breaks apart wood shavings as they pass through the mouth.

- lateral adjustment lever: skews the iron so that the depth of cut is uniform across the mouth.

- tote: the principal handle for gripping the plane.

- cam lever: pivots a sliding section of the forward end of the sole to adjust the gap in the plane's mouth. It is anchored to the threaded post of the knob and secured by tightening the knob.

- frog: an adjustable iron wedge that holds the plane iron at the proper angle and allows it to be varied in depth relative to the sole. The frog is screwed down to the inside of the sole through two parallel slots and on many planes is only adjustable with a screwdriver when the plane iron is removed. Some planes, such as the Stanley Bedrock line and bench planes made by Lie-Nielsen and WoodRiver/Woodcraft, have a screw mechanism that allows the frog to be adjusted without removing the blade.

- sole: the bottom face of the plane.

Types

Most planes fall within the categories (by size) of block plane, smoothing plane, and jointing plane. Specialty planes include the shoulder plane, router plane, bullnose plane, and chisel plane, among others.

Electrically powered hand planers (loosely referred to as power planes) have joined the hand-held plane family.

Bench planes are characterized by having their cutting bevel facing down and attached to a chipbreaker. Most metal bench planes, as well as some larger wooden ones, are designed with a rear handle known as a tote. Block planes are characterized by the absence of a chipbreaker and the cutting iron bedded with the bevel up. The block plane is a smaller tool that can be held with one hand and that excels at working across the grain on a cut end of a board (end grain). It is also good for general purpose work such as taking down a knot in the wood, smoothing small pieces, and chamfering edges.

Different types of bench planes are designed to perform different tasks, the name and size of the plane being defined according to its use. Bailey iron bench planes were designated by number with respect to the length of the plane. This has carried over through the type, regardless of manufacturer. A No. 1 plane is but little more than five inches long. A typical smoothing plane (approx. nine inches) is usually a No. 4, jack planes at about fourteen inches are No. 5, an eighteen-inch fore plane will be a No. 6, and the jointer planes at twenty-two to twenty-four inches in length are No. 7 or 8, respectively. A designation, such as No. 41⁄2 indicates a plane of No. 4 length but slightly wider. A designation such as 51⁄2 indicates the length of a No. 5 but slightly wider (actually, the width of a No. 6 or a No. 7), while a designation such as 51⁄4 indicates the length of a No. 5 but slightly narrower (actually, the width of a No. 3). "Bedrock" versions of the above are simply 600 added to the base number (although no "601" was ever produced, such a plane is indeed available from specialist dealers; 602 through 608, including all the fractionals, were made).

Order of use

A typical order of use in flattening, truing, and smoothing a rough sawn board might be:

- A scrub plane, which removes large amounts of wood quickly, is typically around 9 inches (230 mm) long, but narrower than a smoothing plane, has an iron with a convex cutting edge and has a wider mouth opening to accommodate the ejection of thicker shavings/chips.

- A jack plane is up to 14 inches (360 mm) long, continues the job of roughing out, but with more accuracy and flattening capability than the scrub.

- A jointer plane (including the smaller 14 to 20 inches (360 to 510 mm)[4] fore plane) is between 22 and 30 inches (560 and 760 mm)[4] long, and is used for jointing and final flattening out of boards.

- A smoothing plane, up to 10 inches (250 mm) long, is used to begin preparing the surface for finishing.

- A polishing plane (kanna) is a traditional Japanese plane designed to take a smaller shaving than a Western smoothing plane to create an extremely smooth surface. Polishing planes are the same length as western smoothing planes, and unlike Western planes, which are pushed across a board, is pulled with both hands towards the user.

Material

Planes may also be classified by the material of which they are constructed:

- A wooden plane is entirely wood except for the blade. The iron is held into the plane with a wooden wedge and is adjusted by striking the plane with a hammer.

- A transitional plane has a wooden body with a metal casting set in it to hold and adjust the blade.

- A metal plane is largely constructed of metal, except, perhaps, for the handles.

- An infill plane has a body of metal filled with very dense and hardwood on which the blade rests and the handles are formed. They are typically of English or Scottish manufacture. They are prized for their ability to smooth difficult grained woods when set very finely.

- A side-escapement plane has a tall, narrow, wooden body with an iron held in place by a wedge. They are characterized by the method of shaving ejection. Instead of being expelled from the center of the plane and exiting from the top, these planes have a slit in the side by which the shaving is ejected. On some variations, the slit is accompanied by a circular bevel cut in the side of the plane.

Special purposes

Some special types of planes include:

- The rabbet plane, also known as a rebate or openside plane, which cuts rabbets (rebates) i.e. shoulders, or steps.

- The shoulder plane, is characterized by a cutter that is flush with the edges of the plane, allowing trimming right up to the edge of a workpiece. It is commonly used to clean up dadoes (housings) and tenons for joinery.

- The fillister plane, similar to a rabbet plane, with a fence that registers on the board's edge to cut rabbets with an accurate width.

- The moulding plane, which is used to cut mouldings along the edge of a board.

- The grooving plane which is used to cut grooves along the edge of a board for joining. Grooves are the same as dadoes/housings but are being distinguished by running with the grain.

- The plow/plough plane, which cuts grooves and dadoes (housings) not in direct contact with the edge of the board.

- The router plane, which cleans up the bottom of recesses such as shallow mortises, grooves, and dadoes (housings). Router planes come in several sizes and can also be pressed into service to thickness the cheeks of tenons so that they are parallel to the face of the board.

- The chisel plane, similar to a bullnose plane, but with an exposed blade which allows it to remove wood up to a perpendicular surface such as from the bottom inside of a box.

- The finger plane, which is used for smoothing very small pieces such as toy parts, very thin strips of wood, etc. The very small curved bottom varieties are known as violin makers planes and are used in making stringed instruments.

- The bullnose plane has a very short leading edge, or "toe", to its body, and so can be used in tight spaces; most commonly of the shoulder and rabbet variety. Some bullnose planes have a removable toe so that they can pull double duty as a chisel plane.

- The combination plane, which combines the function of moulding and rabbet planes, which has different cutters and adjustments.

- The circular or compass plane, which utilizes an adjustment system to control the flex on a steel sheet sole and create a uniform curve. A concave setting permits great control for planing large curves, like table sides or chair arms, and the convex works well for chair arms, legs and backs, and other applications. The compass plane, which has a flexible sole with an adjustable curve and is used to plane concave and convex surfaces. Typically used in wooden boat building.

- The toothed plane, which is used for smoothing wood with irregular grain.[5] and for preparing stock for traditional hammer veneering applications.

- The spill plane which creates long, spiraling wood shavings or tapers.

- The spar plane, which is used for smoothing round shapes, like boat masts and chair legs.[6]

- The match plane, which is used for making tongue and groove boards.[7]

- Hollows and rounds are similar to moulding planes, but lack a specific moulding profile. Instead, they cut either a simple concave or convex shape on the face or edge of a board to create a single element of a complex-profile moulding. They are used in pairs or sets of various sizes to create moulding profile elements such as fillets, coves, bullnoses, thumbnails ovolos, ogees, etc. When making mouldings, hollows and rounds must be used together to create the several shapes of the profile. However, they may be used as a single plane to create a simple decorative cove or round-over on the edge of a board. Many of these hollows and rounds can be classified in the category of side-escapement planes.

Use

Planing wood along its side grain should result in thin shavings rising above the surface of the wood as the edge of the plane iron is pushed forward, leaving a smooth surface, but sometimes splintering occurs. This is largely a matter of cutting with the grain or against the grain respectively, referring to the side grain of the piece of wood being worked.

The grain direction can be determined by looking at the edge or side of the work piece. Wood fibers can be seen running out to the surface that is being planed. When the fibers meet the work surface it looks like the point of an arrow that indicates the direction. With some very figured and difficult woods, the grain runs in many directions and therefore working against the grain is inevitable. In this case, a very sharp and finely-set blade is required.

When planing against the grain, the wood fibers are lifted by the plane iron, resulting in a jagged finish, called tearout.

Planing across the grain is sometimes called traverse or transverse planing.

Planing the end grain of the board involves different techniques and frequently different planes designed for working end grain. Block planes and other bevel-up planes are often effective in planing the difficult nature of end grain. These planes are usually designed to use an iron bedded at a low angle, typically about 12 degrees.

See also

- Card scraper

- Cheese slicer, a culinary plane-like tool

- Planer (disambiguation) for other types of planing tools and machines

- Shooting board

- Spokeshave

- Buswartehobel, a plane-shaped bus stop shelter in Zachenberg

Plane-makers

- Alexander Mathieson & Sons, a Scottish plane manufacturer

- Cesar Chelor, earliest documented plane-maker from North America.

- Holtzapffel, a London plane manufacturer

- Lie-Nielsen Toolworks, a U.S. maker of artisan tools

- Millers Falls Company, plane-maker

- T. Norris & Son, a London plane-maker

- Edward Preston & Sons, a plane manufacturer

- Stanley Works, a major US plane manufacturer

- Stewart Spiers, a Scottish plane-maker

- Veritas Tools, a Canadian plane manufacturer

- Tramontina, a Brazilian company

Citations

- ^ C. W. Hampton, E. Clifford (1959). Planecraft. p. 9. C. & J. Hampton Ltd.

- ^ Mercer, Henry C. (1975). Ancient Carpenters' Tools. p. 16. Bucks County, Pennsylvania: Bucks County Historical Society.

- ^ "Planing Ship Timbers with Little Machines". Popular Science. Vol. 93, no. 6. Bonnier Corporation. December 1918. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ a b "Understanding Bench Planes". 14 February 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "Toothed Plane". ECE. Archived from the original on 2014-07-07. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

- ^ "Shaping plane for rounding a spar". The WoodenBoat Forum. March 4, 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ "Stanley No. 148 Match Plane". 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

General and cited references

- Greber, Josef M. (1956, reprinted 1987) Die Geschichte des Hobels. Von der Steinheit bis zur Enstehung der Holzwerkzeugfabriken im frühen 19. Jahrhundert, Zurich, reprinted Hanover: Verlag Th. Schäfer. OCLC 246467323.

- Greber, Josef M., transl. by Seth W. Burchard (1991) The History of the Woodworking Plane from the Stone Age to the Development of Woodworking Factories in the Early 19th Century. Albany, NY: Early American Industries Association. OCLC 602189643.

- Hack, Garrett (1997) The Handplane Book. ISBN 1-56158-155-0.

- Hoadley, R. Bruce (2000) Understanding Wood: A Craftsman’s Guide to Wood Technology. ISBN 1-56158-358-8.

- Russell, David R., with Robert Lesage and photographs by James Austin, cataloguing assisted by Peter Hackett (2010) Antique Woodworking Tools: Their Craftsmanship from the Earliest Times to the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: John Adamson. ISBN 978-1-898565-05-5. OCLC 727125586.

- Salaman, R. A. (1989) Dictionary of Woodworking Tools. ISBN 0-04-440256-2.

- Todd, R., Allen, D., Alting, L., Manufacturing Processes Reference Guide, p. 124, 1994

- Watson, Aldren A. (1982) Hand Tools: Their Ways and Workings. ISBN 1-55821-224-8.

- Whelan, John M. (1993) The Wooden Plane: Its History, Form and Function Mendham, NJ: Astragal Press ISBN 978-1-879335-32-5.

External links

- Handplane Central Information for all types of hand planes, including wooden planes, infill planes and Stanley type planes. Also information on how to make hand planes.

- Catalog of American Patented Antique Tools A pictorial collection of antique planes and other tools showing some of the variety in styles.

- The history, types, collector value and other information on the British hand plane maker Record Planes

- Old woodworking planes Archived 2018-09-07 at the Wayback Machine