The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

The Company of Merchant Adventurers of London was a trading company founded in the City of London in the early 15th century. It brought together leading merchants in a regulated company in the nature of a guild. Its members’ main business was exporting cloth, especially white (undyed) broadcloth, in exchange for a large range of foreign goods.[1][2] It traded in northern European ports, competing with the Hanseatic League. It came to focus on Hamburg.

Origin

The company received its royal charter from King Henry IV in 1407,[3] but its roots may go back to the Fraternity of St. Thomas of Canterbury. It claimed to have liberties existing as early as 1216. The Duke of Brabant granted privileges and in return promised no fees to trading merchants. The company was chiefly chartered to the English merchants at Antwerp in 1305. This body may have included the Staplers, who exported raw wool, as well as the Merchant Adventurers. Henry IV's charter was in favor of the English merchants dwelling in Holland, Zeeland, Brabant, and Flanders. Other groups of merchants traded to different parts of northern Europe, including merchants dwelling in Prussia, Scania, the Sound, and the Hanseatic League (whose election of a governor was approved by Richard II of England in 1391), and the English Merchants in Norway, Sweden and Denmark (who received a charter in 1408).

Under the Tudors

Under Henry VII's charter of 1505, the company had a governor and 24 assistants. The members were trading investors, and most of them were probably mercers of the City of London.[4] However, the company also had members from York, Norwich, Exeter, Ipswich, Newcastle, Hull, and other places. The merchant adventurers of these towns were separate but affiliated bodies. The Society of Merchant Venturers of Bristol was a separate group of investors, chartered by Edward VI in 1552.

Under Henry VII, the merchants who were not of London complained about restraint of trade. They had once traded freely with Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, and the Netherlands, but the London company was imposing a fine of £20, which was driving them out of their markets. Henry VII required the fine to be reduced to 10 marks (£3, 6s and 8d).[5] Conflict arose with the Merchants of the Staple, who sought to diversify from exporting wool through Calais into exporting cloth to Flanders without having to become freemen of the Company of Merchant Adventurers. The Merchant Adventurers kept control of their trade and Flanders as their port. Foreign merchants of the Hanseatic League had considerable privileges in English trade and competed with the Merchant Adventurers, but these privileges were revoked by the English government in the mid-16th century.

The Merchant Adventurers decided to use other ports. Emden in East Friesland and Hamburg competed to serve the Merchant Adventurers of England, who chose Emden. They soon found, however, that the port failed to attract sufficient merchants to buy the English merchants' wares, so they left abruptly and returned to Antwerp. Operations there were interrupted by Queen Elizabeth's seizing Spanish treasure ships, which were conveying money to the Duke of Alva, governor of the Netherlands. Although trade was resumed at Antwerp from 1573 to 1582, its declining fortunes ceased with the fall of the city and the subsequent development of the Amsterdam Entrepôt, and the Dutch Golden Age.

Under the charter of 1564,[6] the company's court consisted of a governor (elected annually by members beyond the seas), his deputies, and 24 Assistants. Admission was by patrimony (being the son of a merchant who was free of the company at the time of the son's birth), service (apprenticeship to a member), redemption (purchase) or 'free gift'. By the time of the accession of James I in 1603, there were at least 200 members. They gradually increased the fees for admission.

Conflict

The conflict of the Merchant Adventurers with the Hanseatic League continued as the latter had the same rights in England as native merchants and better privileges abroad, enabling them to undersell English merchants. Hamburg was a member of the League. When the English merchants left Emden, they tried to settle in Hamburg, but the League forced the city to expel them. Emden was tried again in 1579. The Emperor ordered the Count of East Friesland to expel the merchants, but he declined. The English merchants remained there until 1587. In 1586, the Senate of Hamburg invited the Merchant Adventurers to return there, but negotiations over this broke down.

The merchants who had frequented Middelburg since 1582 were invited to return in 1587 to the (now independent) United Provinces (later part of the Netherlands). Due to impositions by Holland and Zeeland, this was an unpopular choice with company members. In 1611 the company's staple was permanently fixed at Hamburg. The designated Dutch staple port was moved during the early 17th century from Middelburg to Delft in 1621, then to Rotterdam in 1635, then to Dordrecht in 1655.

The years between 1615 and 1689 were marked by periods, starting with the ill-fated Cockayne Project (1614 - 1617),[7] when the company lost and then regained its monopolistic privileges. It moved its staple port from Delft to Rotterdam in 1635. The company suffered from trouble with interlopers, traders who were not 'free of the company' (i.e. members), but who nevertheless traded within its privileged area.

Hamburg Company

When the Company of London lost its exclusive privileges following the Glorious Revolution of 1689, the admission fees were reduced to £2. After Parliament threw the trade open, the company continued to exist as a fellowship of merchants trading to Hamburg. Because they drove a considerable trade there, members were sometimes called the Hamburg Company. The Merchant Adventurers of London still existed at the beginning of the 19th century.

Similar groups colonising North America

In the early seventeenth century, similar groups of investors, referred to as "adventurers", were formed to develop overseas trade and colonies in the New World: the Virginia Company of Adventurers of 1609 (which later split into the London Company settling Jamestown and the Chesapeake Bay area, and the Plymouth Company, which settled New England). In addition, the Company of Adventurers in Canada sent forces during the Thirty Years War that achieved the surrender of Quebec in 1629, and colonized the island of Newfoundland.

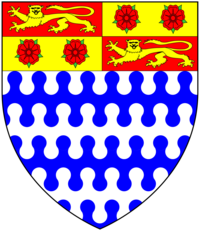

Heraldry

The arms of the various companies were as follows:

- Merchant Adventurers of London: Barry nebulée of six argent and azure, a chief quarterly gules and or on the first and fourth quarters a lion passant guardant of the fourth on the second and third two roses gules barbed vert.[8]

- Merchant Adventurers of Bristol: Barry wavy of eight argent and azure, on a bend or a dragon passant wings indorsed tail extended vert on a chief gules a lion passant guardant of the third between two bezants[9]

- Merchant Adventurers of Exeter: Azure, a tower triple towered or standing on the waves of the sea in base proper in chief two ducal coronets of the second[10]

- Merchant Adventurers of York: Barry wavy of six argent and azure, on a chief per pale gules and azure a lion passant guardant or between two roses argent seeded or (as visible on 1765 escutcheon in Great Hall of Merchant Adventurers' Hall, York;[11])

References

- ^ Robert Brenner, Merchants and revolution: commercial change, political conflict, and London's overseas traders, 1550–1653 (Verso, 2003).

- ^ E. Lipson, The Economic History of England (1956), 2;196–269.

- ^ "Merchant Adventurers" in Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Library Edition, 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Many records of the Court Meetings of the Merchant Adventurers of London are printed in L. Lyell and F.D. Watney (eds), Acts of Court of the Mercers' Company 1453-1527 (Cambridge University Press, 1936).

- ^ £1 = 3 English marks; 1 mark = 6s 8d

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Elizabeth I, Vol. III: 1563-1566 (HMSO London 1960) pp. 178-80, item 922.

- ^ "Astrid Friis. Alderman Cockayne's Project and the Cloth Trade. The Commercial Policy of England in its main aspects, 1603-1625". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ Joseph Edmondson (Mowbray Herald Extraordinary), Robert Glover, Sir Joseph Ayloffe, A Complete Body of Heraldry, Volume 1, The Arms of Societies and Bodies Corporate Established in London, London, 1780(no page numbers)[1]

- ^ Edmondson, Glover & Ayloffe

- ^ Edmondson, Glover & Ayloffe

- ^ 'Merchant Adventurers' Hall', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 5, Central (London, 1981), pp. 81-88. [2] See image File:Merchant Adventurers' Hall - geograph.org.uk - 1505920.jpg[3]

Further reading

- Brenner, Robert. Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London's Overseas Traders, 1550-1653 (Verso, 2003).

- Lipson, E. The Economic History of England I (12th edition, 1959), 570-84; II (6th edition 1956), 196-269.