The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| History of art |

|---|

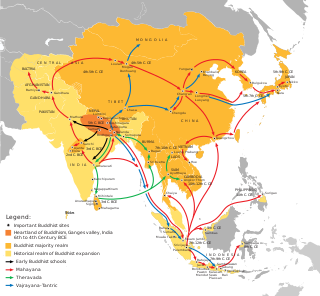

Buddhist art is visual art produced in the context of Buddhism. It includes depictions of Gautama Buddha and other Buddhas and bodhisattvas, notable Buddhist figures both historical and mythical, narrative scenes from their lives, mandalas, and physical objects associated with Buddhist practice, such as vajras, bells, stupas and Buddhist temple architecture.[1] Buddhist art originated in the north of the Indian subcontinent, in modern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, with the earliest survivals dating from a few centuries after the historical life of Siddhartha Gautama from the 6th to 5th century BCE.

As Buddhism spread and evolved in each new host country, Buddhist art followed in its footsteps. It developed to the north through Central Asia and into Eastern Asia to form the Northern branch of Buddhist art, and to the east as far as Southeast Asia to form the Southern branch of Buddhist art. In India, Buddhist art flourished and co-developed with Hindu and Jain art, with cave temple complexes built together, each likely influencing the other.[2]

Initially the emphasis was on devotional statues of the historical Buddha, as well as detailed scenes in relief of his life, and former lives, but as the Buddhist pantheon developed devotional images of bodhisattvas and other figures became common subjects in themselves in Northern Buddhist art, rather than just attendants of the Buddha, and by the late first millennium came to predominate.

History

Pre-iconic phase (5th–1st century BCE)

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE, sculptures became more explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha's life and teachings. These took the form of votive tablets or friezes, usually in relation to the decoration of stupas. Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human form, but only through Buddhist symbolism. This period may have been aniconic.

Artists were reluctant to depict the Buddha anthropomorphically, and developed sophisticated aniconic symbols to avoid doing so (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear). This tendency remained as late as the 2nd century CE in the southern parts of India, in the art of the Amaravati School (see: Mara's assault on the Buddha). It has been argued that earlier anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha may have been made of wood and may have perished since then. However, no related archaeological evidence has been found.

The earliest works of Buddhist art in India date back to the 1st century BCE. The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya became a model for similar structures in Burma and Indonesia. The frescoes at Sigiriya are said to be even older than the Ajanta Caves paintings.[3]

Iconic phase (1st century CE – present)

Chinese historical sources and mural paintings in the Tarim Basin city of Dunhuang accurately describe the travels of the explorer and ambassador Zhang Qian to Central Asia as far as Bactria around 130 BCE, and the same murals describe the Emperor Han Wudi (156–87 BCE) worshiping Buddhist statues, explaining them as "golden men brought in 120 BCE by a great Han general in his campaigns against the nomads." Although there is no other mention of Han Wudi worshiping the Buddha in Chinese historical literature, the murals would suggest that statues of the Buddha were already in existence during the 2nd century BCE, connecting them directly to the time of the Indo-Greeks.

Anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha started to emerge from the 1st century CE in Northern India, with the Bimaran casket. The three main centers of creation have been identified as Gandhara in today's North West Frontier Province, in Pakistan, Amaravati and the region of Mathura, in central northern India.

Hellenistic culture was introduced in Gandhara during the conquests of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. Chandragupta Maurya (r. 321–298 BCE), founder of the Mauryan Empire, conquered the Macedonian satraps during the Seleucid-Mauryan War of 305–303 BCE. Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE), who formed the largest Empire in the Indian subcontinent, converted to Buddhism following the Kalinga War. Abandoning an expansionist ideology, Ashoka worked to spread the religion and philosophy throughout his empire as described in the edicts of Ashoka. Ashoka claims to have converted the Greek populations within his realm to Buddhism:

Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma.[5]

After the overthrow of the Mauryan Empire by the Shunga Empire, the Greco-Bactrian and subsequently the Indo-Greek Kingdoms invaded north-western India. They facilitated the spread of Greco-Buddhist art style to other parts of the subcontinent. The Indo-Greek King Menander I was renown as a great patron of Buddhism, attaining the title of an arhat.[6] Meanwhile, Pushyamitra Shunga persecuted Buddhism, presumably to further erase the legacy of the Mauryan Empire.[7] This led to the decline of Buddhist art east of Mathura.

Gandharan Buddhist sculpture displays Hellenistic artistic influence in the forms of human figures and ornament. Figures were much larger than any known from India previously, and also more naturalistic, and new details included wavy hair, drapery covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, and acanthus leaf ornament.[citation needed]

The art of Mathura tends to be based on an Indian tradition, exemplified by the anthropomorphic representation of divinities such as the Yaksas, although in a style rather archaic compared to the later representations of the Buddha. The Mathuran school contributed clothes covering the left shoulder of thin muslin, the wheel on the palm, the lotus seat.[citation needed]

Mathura and Gandhara also influenced each other. During their artistic florescence, the two regions were even united politically under the Kushans, both being capitals of the empire. It is still a matter of debate whether the anthropomorphic representations of Buddha was essentially a result of a local evolution of Buddhist art at Mathura, or a consequence of Greek cultural influence in Gandhara through the Greco-Buddhist syncretism.

This iconic art was characterized from the start by a realistic idealism, combining realistic human features, proportions, attitudes and attributes, together with a sense of perfection and serenity reaching to the divine. This expression of the Buddha as both man and God became the iconographic canon for subsequent Buddhist art.[citation needed]

Remains of early Buddhist painting in India are vanishingly rare, with the later phases of the Ajanta Caves giving the great majority of surviving work, created over a relatively short up to about 480 CE. These are highly sophisticated works, evidently produced in a well-developed tradition, probably painting secular work in palaces as much as religious subjects.

Buddhist art continued to develop in India for a few more centuries. The pink sandstone sculptures of Mathura evolved during the Gupta period (4th to 6th century CE) to reach a very high fineness of execution and delicacy in the modeling. The art of the Gupta school was extremely influential almost everywhere in the rest of Asia. At the end of the 12th century CE, Buddhism in its full glory came to be preserved only in the Himalayan regions in India. These areas, helped by their location, were in greater contact with Tibet and China – for example the art and traditions of Ladakh bear the stamp of Tibetan and Chinese influence.

As Buddhism expanded outside of India from the 1st century CE, its original artistic package blended with other artistic influences, leading to a progressive differentiation among the countries adopting the faith.

- A Northern route was established from the 1st century CE through Central Asia, Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, in which Mahayana Buddhism prevailed.

- A Southern route, where Theravada Buddhism dominated, went through Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

Northern Buddhist art

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism to Central Asia, China and ultimately Korea and Japan started in the 1st century CE with a semi-legendary account of an embassy sent to the West by the Chinese Emperor Ming (58–75 CE). However, extensive contacts started in the 2nd century CE, probably as a consequence of the expansion of the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory of the Tarim Basin, with the missionary efforts of a great number of Central Asian Buddhist monks to Chinese lands. The first missionaries and translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese, such as Lokaksema, were either Parthian, Kushan, Sogdian or Kuchean.

Central Asian missionary efforts along the Silk Road were accompanied by a flux of artistic influences, visible in the development of Serindian art from the 2nd through the 11th century in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. Serindian art often derives from the Greco-Buddhist art of the Gandhara district of what is now Pakistan, combining Indian, Greek and Roman influences. Silk Road Greco-Buddhist iconography may have influenced the Japanese god Fūjin.[9]

The art of the northern route was also highly influenced by the development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, an inclusive branch of Buddhism characterized by the adoption of new texts, in addition to the traditional āgamas, and a shift in the understanding of Buddhism. Mahāyāna goes beyond the traditional Early Buddhist ideal of the release from suffering (duḥkha) of arhats, and emphasizes the bodhisattva path. The Mahāyāna sutras elevate the Buddha to a transcendent and infinite being, and feature a pantheon of bodhisattvas devoting themselves to the Six Perfections, ultimate knowledge (Prajñāpāramitā), enlightenment, and the liberation of all sentient beings. Northern Buddhist art thus tends to be characterized by a very rich and syncretic Buddhist pantheon, with a multitude of images of the various buddhas, bodhisattvas, and heavenly beings (devas).

Afghanistan

Buddhist art in Afghanistan (old Bactria) persisted for several centuries until the spread of Islam in the 7th century. It is exemplified by the Buddhas of Bamyan. Other sculptures, in stucco, schist or clay, display very strong blending of Indian post-Gupta mannerism and Classical influence, Hellenistic or possibly even Greco-Roman.

Although Islamic rule was limited tolerant of other religions "of the Book", it showed zero tolerance for Buddhism, which was perceived as a religion depending on "idolatry". Human figurative art forms also being prohibited under Islam, Buddhist art suffered numerous attacks, which culminated with the systematic destructions by the Taliban regime. The Buddhas of Bamyan, the sculptures of Hadda, and many of the remaining artifacts at the Afghanistan museum have been destroyed.

The multiple conflicts since the 1980s also have led to a systematic pillage of archaeological sites apparently in the hope of reselling in the international market what artifacts could be found.

Central Asia

Central Asia long played the role of a meeting place between China, India and Persia. During the 2nd century BCE, the expansion of the Former Han to the West led to increased contact with the Hellenistic civilizations of Asia, especially the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom.

Thereafter, the expansion of Buddhism to the North led to the formation of Buddhist communities and even Buddhist kingdoms in the oasis of Central Asia. Some Silk Road cities consisted almost entirely of Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and it seems that one of their main objectives was to welcome and service travelers between East and West.

The eastern part of Central Asia (Chinese Turkestan (Tarim Basin, Xinjiang) in particular has revealed an extremely rich Serindian art (wall paintings and reliefs in numerous caves, portable paintings on canvas, sculpture, ritual objects), displaying multiple influences from Indian and Hellenistic cultures. Works of art reminiscent of the Gandharan style, as well as scriptures in the Gandhari script Kharoshti have been found. These influences were rapidly absorbed however by the vigorous Chinese culture, and a strongly Chinese particularism develops from that point.

China

Buddhism arrived in China around the 1st century CE, and introduced new types of art into China, particularly in the area of statuary. Receiving this distant religion, strong Chinese traits were incorporated into Buddhist art.

-

A Chinese Northern Wei Buddha Maitreya, 443 CE

-

A seated Maitreya statue Northern Wei, 512 CE

-

Tang Bodhisattva

Northern dynasties

In the 5th to 6th centuries, the Northern dynasties developed rather symbolic and abstract modes of representation, with schematic lines. Their style is also said to be solemn and majestic. The lack of corporeality of this art, and its distance from the original Buddhist objective of expressing the pure ideal of enlightenment in an accessible and realistic manner, progressively led to a change towards more naturalism and realism, leading to the expression of Tang Buddhist art.

Sites preserving Northern Wei dynasty Buddhist sculpture:

Tang dynasty—Qing dynasty

Following a transition under the Sui dynasty, Buddhist sculpture of the Tang evolved towards a markedly lifelike expression. Because of the dynasty's openness to foreign influences, and renewed exchanges with Indian culture due to the numerous travels of Chinese Buddhist monks to India, Tang dynasty Buddhist sculpture assumed a rather classical form, inspired by the Indian art of the Gupta period. During that time, the Tang capital of Chang'an (today's Xi'an) became an important center for Buddhism. From there Buddhism spread to Korea, and Japanese missions to Tang China helped it gain a foothold in Japan. Foreign influences came to be negatively perceived in China towards the end of the Tang dynasty. In the year 845, the Tang emperor Wuzong outlawed all "foreign" religions (including Christian Nestorianism, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism) in order to support the indigenous religion, Taoism. He confiscated Buddhist possessions, and forced the faith to go underground, therefore affecting the development of the religion and its arts in China.

After the Tang dynasty, Buddhism continued to receive official patronage in several states during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, which continued under the successive Liao, Jin, Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties. This was marked by construction of new monumental Buddhist artwork at grottoes, such as the massive Buddha sculptures at the Dazu Rock Carvings in Sichuan province, as well as at temples, such as the giant esoteric statues of the Bodhisattva Guanyin in Longxing Temple and Dule Temple.[10][11][12] The various Chinese Buddhist traditions, such as Tiantai and Huayan, experienced revivals. Chan Buddhism, in particular, rose to great prominence under the Song dynasty. Early paintings by Chan monks tended to eschew the meticulous realism of Gongbi painting in favour of vigorous, monochrome paintings, attempting to express the impact of enlightenment through their brushwork.[13] The rise of Neo-Confucianism under Zhu Xi in the twelfth century resulted in considerable criticism of the monk-painters by the literati. Despite this, Chan ink paintings continued to be practiced by monastics through the Yuan (1271–1368) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties well into the Qing (1644–1912) dynasty.[14][15][16] Aside from Chan ink paintings, other forms of painting also proliferated, especially during the Ming dynasty, such as the Water and Land Ritual paintings and mural art which depict various Buddhist divinities and other figures.[17]

During the Qing dynasty, Manchu emperors supported Buddhist practices for a range of political and personal reasons. The Shunzhi Emperor was a devotee of Chan Buddhism, while his successor, the Kangxi Emperor promoted Tibetan Buddhism, claiming to be the human embodiment of the bodhisattva Manjusri.[18] However, it was under the rule of the third Qing ruler, the Qianlong Emperor, that imperial patronage of the Buddhist arts reached its height in this period. He commissioned a vast number of religious works in the Tibetan style, many of which depicted him in various sacred guises.[19] Works of art produced during this period are characterized by a unique fusion of Tibetan and Chinese artistic approaches. They combine a characteristically Tibetan attention to iconographic detail with Chinese-inspired decorative elements. Inscriptions are often written in Chinese, Manchu, Tibetan, Mongolian and Sanskrit, while paintings are frequently rendered in vibrant colors.[20] Additionally, the Qianlong Emperor initiated a number of large-scale construction projects; in 1744 he rededicated the Yonghe Temple as Beijing's main Tibetan Buddhist monastery, donating a number of valuable religious paintings, sculptures, textiles and inscriptions to the temple.[21] The Xumi Fushou Temple, and the works housed within, is another project commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor that embodies the unique blend of Chinese, Tibetan and Manchurian artistic styles that characterized some of the Buddhist art produced in China under Qianlong's reign. After the Qianlong Emperor's abdication in 1795, the popularity of Tibetan Buddhism at the Qing court declined. The motives behind the Qing emperors' promotion of Tibetan Buddhism have been interpreted as a calculated act of political manipulation, and a means of forging ties between Manchu, Mongolian, and Tibetan communities, though this has been challenged by recent scholarship.[22]

Legacy

The popularization of Buddhism in China has made the country home to the richest collections of Buddhist arts in the world. The Mogao Caves near Dunhuang and the Bingling Temple caves near Yongjing in Gansu province, the Longmen Grottoes near Luoyang in Henan province, the Yungang Grottoes near Datong in Shanxi province, and the Dazu Rock Carvings near Chongqing municipality are among the most important and renowned Buddhist sculptural sites. The Leshan Giant Buddha, carved out of a hillside in the 8th century during the Tang dynasty and looking down on the confluence of three rivers, is still the largest stone Buddha statue in the world. Numerous temples throughout China still preserve various Buddhist statues and paintings from previous dynasties. In addition, Buddhist sculptures are still produced in contemporary times mainly for enshrinement in Buddhist temples and shrines.

Korea

Korean Buddhist art generally reflects an interaction between other Buddhist influences and a strongly original Korean culture. Additionally, the art of the steppes, particularly Siberian and Scythian influences, are evident in early Korean Buddhist art based on the excavation of artifacts and burial goods such as Silla royal crowns, belt buckles, daggers, and comma-shaped gogok.[23][24] The style of this indigenous art was geometric, abstract and richly adorned with a characteristic "barbarian" luxury[clarify]. Although many other influences were strong, Korean Buddhist art, "bespeaks a sobriety, taste for the right tone, a sense of abstraction but also of colours that curiously enough are in line with contemporary taste" (Pierre Cambon, Arts asiatiques – Guimet').[citation needed]

Three Kingdoms of Korea

The first of the Three Kingdoms of Korea to officially receive Buddhism was Goguryeo in 372.[25] However, Chinese records and the use of Buddhist motifs in Goguryeo murals indicate the introduction of Buddhism earlier than the official date.[26] The Baekje Kingdom officially recognized Buddhism in 384.[25] The Silla Kingdom, isolated and with no easy sea or land access to China, officially adopted Buddhism in 535 although the foreign religion was known in the kingdom due to the work of Goguryeo monks since the early 5th century.[27] The introduction of Buddhism stimulated the need for artisans to create images for veneration, architects for temples, and the literate for the Buddhist sutras and transformed Korean civilization. Particularly important in the transmission of sophisticated art styles to the Korean kingdoms was the art of the "barbarian" Tuoba, a clan of non-Han Chinese Xianbei people who established the Northern Wei dynasty in China in 386. The Northern Wei style was particularly influential in the art of the Goguryeo and Baekje. Baekje artisans later transmitted this style along with Southern dynasty elements and distinct Korean elements to Japan. Korean artisans were highly selective of the styles they incorporated and combined different regional styles together to create a specific Korean Buddhist art style.[28][29]

While Goguryeo Buddhist art exhibited vitality and mobility akin with Northern Wei prototypes, the Baekje Kingdom was also in close contact with the Southern dynasties of China and this close diplomatic contact is exemplified in the gentle and proportional sculpture of the Baekje, epitomized by Baekje sculpture exhibiting the fathomless smile known to art historians as the Baekje smile.[30] The Silla Kingdom also developed a distinctive Buddhist art tradition epitomized by the Bangasayusang, a half-seated contemplative statue of Maitreya whose Korean-made twin was sent to Japan as a proselytizing gift and now resides in the Koryu-ji Temple in Japan.[31]

Buddhism in the Three Kingdoms period stimulated massive temple-building projects, such as the Mireuksa Temple in the Baekje Kingdom and the Hwangnyongsa Temple in Silla. Baekje architects were famed for their skill and were instrumental in building the massive nine-story pagoda at Hwangnyongsa and early Buddhist temples in Yamato Japan such as Hōkō-ji (Asuka-dera) and Hōryū-ji.[32] 6th century Korean Buddhist art exhibited the cultural influences of China and India but began to show distinctive indigenous characteristics.[33] These indigenous characteristics can be seen in early Buddhist art in Japan and some early Japanese Buddhist sculpture is now believed to have originated in Korea, particularly from Baekje, or Korean artisans who immigrated to Yamato Japan. Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues. Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552.[34]

Unified Silla

During the Unified Silla period, East Asia was particularly stable with China and Korea both enjoying unified governments. Early Unified Silla art combined Silla styles and Baekje styles. Korean Buddhist art was also influenced by new Tang dynasty styles as evidenced by a new popular Buddhist motif with full-faced Buddha sculptures. Tang China was the cross roads of East, Central, and South Asia and so the Buddhist art of this time period exhibit the so-called international style. State-sponsored Buddhist art flourished during this period, the epitome of which is the Seokguram Grotto.

Goryeo dynasty

The fall of the Unified Silla dynasty and the establishment of the Goryeo dynasty in 918 indicates a new period of Korean Buddhist art. The Goryeo kings also lavishly sponsored Buddhism and Buddhist art flourished, especially Buddhist paintings and illuminated sutras written in gold and silver ink. [1]. The crowning achievement of this period is the carving of approximately 80,000 woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana which was done twice.

Joseon dynasty

The Joseon dynasty actively suppressed Buddhism beginning in 1406 and Buddhist temples and art production subsequently decline in quality in quantity although beginning in 1549, Buddhist art does continue to be produced. [2].

Japan

Before the introduction of Buddhism, Japan had already been the seat of various cultural (and artistic) influences, from the abstract linear decorative art of the indigenous Neolithic Jōmon from around 10500 BCE to 300 BCE, to the art during the Yayoi and Kofun periods, with developments such as Haniwa art.

The cultural exchange between India and Japan was not direct, as Japan received Buddhism through Korea, China, Central Asia and eventually India. The Japanese discovered Buddhism in the 6th century when missionary monks travelled to the islands together with numerous scriptures and works of art. The cultural contact between Indian Dharmic civilization and Japan through the adoption of Buddhist ideas and aesthetic has contributed to the development of a national cultural order in the subsequent century.[35] The Buddhist religion was adopted by the state in the following century. Being geographically at the end of the Silk Road, Japan was able to preserve many aspects of Buddhism at the very time it was disappearing in India, and being suppressed in Central Asia.

From 711, numerous temples and monasteries were built in the capital city of Nara, including a five-story pagoda, the Golden Hall of the Horyuji, and the Kōfuku-ji temple. Countless paintings and sculptures were made, often under governmental sponsorship. Indian, Hellenistic, Chinese and Korean artistic influences blended into an original style characterized by realism and gracefulness.

The creation of Japanese Buddhist art was especially rich between the 8th and 13th centuries during the periods of Nara, Heian and Kamakura. Japan developed an extremely rich figurative art for the pantheon of Buddhist deities, sometimes combined with Hindu and Shinto influences. This art can be very varied, creative and bold. Jōchō is said to be one of the greatest Buddhist sculptors not only in Heian period but also in the history of Buddhist statues in Japan. Jōchō redefined the body shape of Buddha statues by perfecting the technique of "yosegi zukuri" (寄木造り) which is a combination of several woods. The peaceful expression and graceful figure of the Buddha statue that he made completed a Japanese style of sculpture of Buddha statues called "Jōchō yō" (Jōchō style, 定朝様) and determined the style of Japanese Buddhist statues of the later period. His achievement dramatically raised the social status of busshi (Buddhist sculptor) in Japan.[36]

In the Kamakura period, the Minamoto clan established the Kamakura shogunate and the samurai class virtually ruled Japan for the first time. Jocho's successors, sculptors of the Kei school of Buddhist statues, created realistic and dynamic statues to suit the tastes of samurai, and Japanese Buddhist sculpture reached its peak. Unkei, Kaikei, and Tankei were famous, and they made many new Buddha statues at many temples such as Kofuku-ji, where many Buddha statues had been lost in wars and fires.[37] One of the most outstanding Buddhist arts of the period was the statue of Buddha enshrined in Sanjūsangen-dō consisting of 1032 statues produced by sculptors of Buddhist statues of the Kei school, In school and En school. The 1 principal image Senju Kannon in the center, the surrounding 1001 Senju Kannon, the 28 attendants of Senju Kannon, Fūjin and Raijin create a solemn space, and all Buddha statues are designated as National Treasures.[38][39]

From the 12th and 13th, a further development was Zen art, and it faces golden days in Muromachi Period, following the introduction of the faith by Dogen and Eisai upon their return from China. Zen art is mainly characterized by original paintings (such as sumi-e) and poetry (especially haikus), striving to express the true essence of the world through impressionistic and unadorned "non-dualistic" representations. The search for enlightenment "in the moment" also led to the development of other important derivative arts such as the Chanoyu tea ceremony or the Ikebana art of flower arrangement. This evolution went as far as considering almost any human activity as an art with a strong spiritual and aesthetic content, first and foremost in those activities related to combat techniques (martial arts).

Buddhism remains very active in Japan to this day. Around 80,000 Buddhist temples are preserved, and many of them are in wood and are regularly restored.

-

Senju Kannon by Tankei. Sanjūsangen-dō, 1254. National Treasure.

-

Scroll calligraphy of Bodhidharma, by Hakuin Ekaku (1686 to 1769)

Tibet and Bhutan

Tantric Buddhism started as a movement in Mahayana Buddhism in eastern India around the 5th or the 6th century. Monastic Tantrism became the dominant form of Buddhism in Tibet from the 8th century, and it survived there after the collapse of Buddhism in India, and the largest influence on it is probably the now largely vanished art of north-eastern India. Due to its geographical centrality in Asia, Tibetan Buddhist art also received influences from Indian, Nepali, and Chinese art.

Painted thankas, paintings in manuscripts and small bronzes are typically the finest forms of Tibetan art. One of the most characteristic creations of Tibetan Buddhist art are the mandalas, diagrams of a "divine temple" made of a circle enclosing a square, the purpose of which is to help Buddhist devotees focus their attention through meditation and follow the path to the central image of the Buddha. These are usually temporary, laid out on a floor for a festival, then swept away.

In 10th to 11th centuries, Tabo Monastery in Himachal Pradesh, Northern India (at that time part of Western Tibet Kingdom) serves an important role as an intermediary between India and Tibet cultural exchange, especially Buddhist art and philosophy. Notable example of Tibetan Buddhist art in Tabo is its exquisite frescoes.[40]

Vietnam

Chinese influence was predominant in the north of Vietnam (Tonkin) between the 1st and 9th centuries, and Confucianism and Mahayana Buddhism were prevalent. Overall, the art of Vietnam has been strongly influenced by Chinese Buddhist art.

In the south thrived the former kingdom of Champa (before it was later overtaken by the Vietnamese from the north). Champa had a strongly Indianized art, just as neighboring Cambodia. Many of its statues were characterized by rich body adornments. The capital of the kingdom of Champa was annexed by Vietnam in 1471, and it totally collapsed in the 1720s, while Cham people remain an abundant minority across Southeast Asia.

-

The thousand-armed Quan Âm was carved in the Lê - Nguyễn dynasties, currently on display at the French Guimet Museum

Southern Buddhist art

The orthodox forms of Buddhism, also known as Southern Buddhism are still practised in Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. During the 1st century CE, the trade on the overland Silk Road tended to be restricted by the rise of the Parthian empire in the Middle East, an unvanquished enemy of Rome, just as Romans were becoming extremely wealthy and their demand for Asian luxury was rising. This demand revived the sea connections between the Mediterranean Sea and China, with India as the intermediary of choice. From that time, through trade connections, commercial settlements, and even political interventions, India started to strongly influence Southeast Asian countries. Trade routes linked India with southern Burma, central and southern Siam, lower Cambodia and southern Vietnam, and numerous urbanized coastal settlements were established there.

For more than a thousand years, Indian influence was therefore the major factor that brought a certain level of cultural unity to the various countries of the region. The Pali and Sanskrit languages and the Indian script, together with Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism, Brahmanism and Hinduism, were transmitted from direct contact and through sacred texts and Indian literature such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. This expansion provided the artistic context for the development of Buddhist art in these countries, which then developed characteristics of their own.

Between the 1st and 8th centuries, several kingdoms competed for influence in the region (particularly the Cambodian Funan then the Burmese Mon kingdoms) contributing various artistic characteristics, mainly derived from the Indian Gupta style. Combined with a pervading Hindu influence, Buddhist images, votive tablets and Sanskrit inscriptions are found throughout the area. Between 8th- and 12th-century, under the patronage of Pala dynasty, arts and ideas of Buddhism and Hinduism co-developed and became increasingly intermeshed.[41] However, with Muslim invasion and sacking of monasteries in India, states Richard Blurton, "Buddhism collapsed as a major force in India".[41]

By the 8th to 9th century, Shailendran Buddhist art were developed and flourished in Mataram Kingdom of Central Java, Indonesia. This period marked the renaissance of Buddhist art in Java, as numerous exquisite monuments were built, including Kalasan, Manjusrigrha, Mendut and Borobudur stone mandala. The traditions would continue to the 13th century Singhasari Buddhist art of East Java.

From the 9th to the 13th centuries, Southeast Asia had very powerful empires and became extremely active in Buddhist architectural and artistic creation. The Sri Vijaya Empire to the south and the Khmer Empire to the north competed for influence, but both were adherents of Mahayana Buddhism, and their art expressed the rich Mahayana pantheon of the Bodhisattvas. The Theravada Buddhism of the Pali canon was introduced to the region around the 13th century from Sri Lanka, and was adopted by the newly founded ethnic Thai kingdom of Sukhothai. Since in Theravada Buddhism of the period, Monasteries typically were the central places for the laity of the towns to receive instruction and have disputes arbitrated by the monks, the construction of temple complexes plays a particularly important role in the artistic expression of Southeast Asia from that time.

From the 14th century, the main factor was the spread of Islam to the maritime areas of Southeast Asia, overrunning Malaysia, Indonesia, and most of the islands as far as the Southern Philippines. In the continental areas, Theravada Buddhism continued to expand into Burma, Laos and Cambodia.

Sri Lanka

According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced in Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE by Indian missionaries under the guidance of Thera Mahinda, the son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka. Prior to the expansion of Buddhism, the indigenous population of Sri Lanka lived in an animistic world full of superstition. The assimilation and conversion of the various pre-Buddhist beliefs was a slow process. In order to gain a foothold among the rural population, Buddhism needed to assimilate the various categories of spirits and other supernatural beliefs.[citation needed] The earliest monastic complex was the Mahāvihāra at Anurādhapura founded by Devānampiyatissa and presented to Mahinda Thera. The Mahāvihāra became the centre of the orthodox Theravāda doctrine and its supreme position remained unchallenged until the foundation of the Abhayagiri Vihāra around 89 BCE by Vaţţagāmaņĩ.

The Abhayagiri Vihāra became the seat of the reformed Mahāyāna doctrines. The rivalry between the monks of the Mahāvihāra and the Abhayagiri led to a further split and the foundation of the Jetavanarama near the Mahāvihāra. The main feature of Sinhala Buddhism was its division into three major groups, or nikāyas, named after the three main monastic complexes at Anurādhapura; the Mahāvihāra, the Abhayagiri, and the Jetavanārāma. This was the result in the deviations in the disciplinary rules (vinaya) and doctrinal disputes. All the other monasteries of Sri Lanka owed ecclesiastical allegiance to one of the three. Sri Lanka is famous for its creations of Buddhist sculptures made of stone and cast in bronze alloy.[42]

Myanmar

A neighbor of India, Myanmar (Burma) was naturally strongly influenced by the eastern part of Indian territory. The Mon of southern Burma are said to have been converted to Buddhism around 200 BCE under the proselytizing of the Indian king Ashoka, before the schism between Mahayana and Hinayana Buddhism.

Early Buddhist temples are found, such as Beikthano in central Myanmar, with dates between the 1st and the 5th centuries. The Buddhist art of the Mons was especially influenced by the Indian art of the Gupta and post-Gupta periods, and their mannerist style spread widely in Southeast Asia following the expansion of the Mon Empire between the 5th and 8th centuries.

Later, thousands of Buddhist temples were built at Bagan, the capital, between the 11th and 13th centuries, and around 2,000 of them are still standing. Beautiful jeweled statues of the Buddha are remaining from that period. Creation managed to continue despite the seizure of the city by the Mongols in 1287.

During the Ava period, from the 14th to 16th centuries, the Ava (Innwa) style of the Buddha image was popular. In this style, the Buddha has large protruding ears, exaggerated eyebrows that curve upward, half-closed eyes, thin lips and a hair bun that is pointed at the top, usually depicted in the bhumisparsa mudra.[43]

During the Konbaung dynasty, at the end of the 18th century, the Mandalay style of the Buddha image emerged, a style that remains popular to this day.[44] There was a marked departure from the Innwa style, and the Buddha's face is much more natural, fleshy, with naturally-slanted eyebrows, slightly slanted eyes, thicker lips, and a round hair bun at the top. Buddha images in this style can be found reclining, standing or sitting.[45] Mandalay-style Buddhas wear flowing, draped robes.

Another common style of Buddha images is the Shan style, from the Shan people, who inhabit the highlands of Myanmar. In this style, the Buddha is depicted with angular features, a large and prominently pointed nose, a hair bun tied similar to Thai styles, and a small, thin mouth.[46]

-

A Mandalay-style statue of Buddha

-

Scenes from the life of the Buddha in an 18th-century Burmese watercolour

Cambodia

Cambodia was the center of the Funan kingdom, which expanded into Burma and as far south as Malaysia between the 3rd and 6th centuries. Its influence seems to have been essentially political, most of the cultural influence coming directly from India.

Later, from the 9th to 13th centuries, the Mahayana Buddhist and Hindu Khmer Empire dominated vast parts of the Southeast Asian peninsula, and its influence was foremost in the development of Buddhist art in the region. Under the Khmer, more than 900 temples were built in Cambodia and in neighboring Thailand and Laos. The royal patronage for Khmer Buddhist art reached its new height with the patronage of Jayavarman VII, a Buddhist king that built Angkor Thom walled city, adorned with the smiling face of Lokeshvara in Angkor Thom dvaras (gates) and prasat towers Bayon.[47] Angkor was at the center of this development, with a Buddhist temple complex and urban organization able to support around 1 million urban dwellers. A great deal of Cambodian Buddhist sculpture is preserved at Angkor; however, organized looting has had a heavy impact on many sites around the country.

Often, Khmer art manages to express intense spirituality through divinely beaming expressions, in spite of spare features and slender lines.

Thailand

The Thai Buddhist art encompasses period for more than a millennia, from pre Thai culture of Dvaravati and Srivijaya, to the first Thai capital of Thai 13th century Sukhothai, all the way to succeeding Thai kingdoms of Ayutthaya and Rattanakosin.[48]

From the 1st to the 7th centuries, Buddhist art in Thailand was first influenced by direct contact with Indian traders and the expansion of the Mon kingdom, leading to the creation of Hindu and Buddhist art inspired from the Gupta tradition, with numerous monumental statues of great virtuosity.

From the 9th century, the various schools of Thai art then became strongly influenced by Cambodian Khmer art in the north and Sri Vijaya art in the south, both of Mahayana faith. Up to the end of that period, Buddhist art is characterized by a clear fluidness in the expression, and the subject matter is characteristic of the Mahayana pantheon with multiple creations of Bodhisattvas.

From the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism was introduced from Sri Lanka around the same time as the ethnic Thai kingdom of Sukhothai was established.[48] The new faith inspired highly stylized images in Thai Buddhism, with sometimes very geometrical and almost abstract figures.

During the Ayutthaya period (14th–18th centuries), the Buddha came to be represented in a more stylistic manner with sumptuous garments and jeweled ornamentations. Many Thai sculptures or temples tended to be gilded, and on occasion enriched with inlays.

The ensuing period of Thonburi and Rattanakosin Kingdom saw the further development of Thai Buddhist art.[48] By the 18th century, Bangkok was established as the royal center of the kingdom of Siam. Subsequently, the Thai rulers filled the city with imposing Buddhist monuments to demonstrate their Buddhist piety as well as to showcase their authority. Among others are the celebrated Wat Phra Kaew which hosts the Emerald Buddha. Other Buddhist temples in Bangkok includes Wat Arun with prang style towers, and Wat Pho with its famous image of Reclining Buddha.

Indonesia

Like the rest of Southeast Asia, Indonesia seems to have been most strongly influenced by India from the 1st century CE. The islands of Sumatra and Java in western Indonesia were the seat of the empire of Sri Vijaya (8th–13th century), which came to dominate most of the area around the Southeast Asian peninsula through maritime power. The Sri Vijayan Empire had adopted Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, under a line of rulers named the Shailendra. The Shailendras was the ardent temple builder and the devoted patron of Buddhism in Java.[49] Sri Vijaya spread Mahayana Buddhist art during its expansion into the Southeast Asian peninsula. Numerous statues of Mahayana Bodhisattvas from this period are characterized by a very strong refinement and technical sophistication, and are found throughout the region. One of the earliest Buddhist inscription in Java, the Kalasan inscription dated 778, mentioned about the construction of a temple for the goddess Tara.[49]

Extremely rich and refined architectural remains are found in Java and Sumatra. The most magnificent is the temple of Borobudur (the largest Buddhist structure in the world, built around 780–850 AD), built by Shailendras.[49] This temple is modelled after the Buddhist concept of universe, the Mandala which counts 505 images of the seated Buddha and unique bell-shaped stupa that contains the statue of Buddha. Borobudur is adorned with long series of bas-reliefs narrated the holy Buddhist scriptures.[50] The oldest Buddhist structure in Indonesia probably is the Batujaya stupas at Karawang, West Java, dated from around the 4th century. This temple is some plastered brick stupas. However, Buddhist art in Indonesia reach the golden era during the Shailendra dynasty rule in Java. The bas-reliefs and statues of Boddhisatva, Tara, and Kinnara found in Kalasan, Sewu, Sari, and Plaosan temple is very graceful with serene expression, While Mendut temple near Borobudur, houses the giant statue of Vairocana, Avalokitesvara, and Vajrapani.

In Sumatra Sri Vijaya probably built the temple of Muara Takus, and Muaro Jambi. The most beautiful example of classical Javanese Buddhist art is the serene and delicate statue of Prajnaparamita of Java (the collection of National Museum Jakarta) the goddess of transcendental wisdom from Singhasari kingdom.[51] The Indonesian Buddhist Empire of Sri Vijaya declined due to conflicts with the Chola rulers of India, then followed by Majapahit empire.

-

A Buddha in Borobudur

-

The statue of Prajñāpāramitā from Singhasari, East Java, on a lotus throne

Philippines

Philippine archaeology has found Buddhist artifacts,[54][55] The style exhibits Vajrayāna influence,[56][57][58] most of them dated to the 9th century. They reflect the iconography of the Śrīvijayan empire's Vajrayāna and its influences on the Philippines's early states. The artifacts' distinct features point to their production in the islands, and suggest artisan's or goldsmith's knowledge of Buddhist culture and literature, and the presence of Buddhist believers. The find-spots extend from the Agusan-Surigao area in Mindanao island to Cebu, Palawan, and Luzon islands. Hence, Vajrayāna ritualism must have spread far and wide throughout the archipelago.

Roman Egypt

The Berenike Buddha is a rare example of Buddhist art that was discovered in 2018–2022 in an archaeological excavation in the ancient harbour of Berenike, Egypt. The statue was discovered in the forecourt of an early Roman period temple dedicated to the Goddess Isis.[59][60]

The statue is the first statue of the Buddha to be ever found west of Afghanistan.[60] It attests to the extent of Indo-Roman relations in the early centuries of our era.[60] Based on stylistic details and the archaeological context of the excavation, it thought that the statue was made in Alexandria around the second century CE.[60] According to Steven Sidebotham, a history professor at the University of Delaware who is co-director of the Berenike Project, the statue dates to between 90 and 140 CE.[61] It was made from a stone that was extracted south of Istanbul, and may also have been carved in Berenike itself.[62] The statue has a halo around the head of the Buddha, decorated with the rays of the sun, and has a lotus flower by his side.[60] It is 71 cm tall.[62]

Various fragmentary parts of Buddha statues (torsos, heads) had already been discovered at Berenike in 2019, some made of local gypsum.[63][64]

Contemporary Buddhist art

Many contemporary artists have made use of Buddhist themes. Notable examples are Bill Viola, in his video installations,[65] John Connell, in sculpture,[66] and Allan Graham in his multi-media "Time is Memory".[67]

In the UK The Network of Buddhist Organisations has interested itself in identifying Buddhist practitioners across all the arts. In 2005 it co-ordinated the UK-wide Buddhist arts festival, "A Lotus in Flower";[68] in 2009 it helped organise the two-day arts conference, "Buddha Mind, Creative Mind".[69] As a result of the latter an association of Buddhist artists was formed.[70]

-

The Final Release, by Abanindranath Tagore. Illustration from the book Buddha and the gospel of Buddhism (1916)

-

Quan Âm in contemporary Vietnamese art

See also

- Buddharupa

- Buddhist architecture

- Buddhist music

- Buddhist symbolism

- Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta

- Depictions of Gautama Buddha in film

- Early Buddhist Texts

- Gautama Buddha & Buddhism

- Great Renunciation & Four sights

- Leela Attitude

- Mahaparinibbana Sutta

- Māravijaya Attitude

- Meditation Attitude

- Naga Prok Attitude

- Physical characteristics of the Buddha

- Relics associated with Buddha

- Samaññaphala Sutta

Citations

- ^ "What is Buddhist Art?". Buddhist Art News. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ T. Richard Blurton (1994), Hindu Art, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674391895, pp. 113–116, 160–162, 191–192

- ^ Buddhist Art Frontline Magazine 13–26 May 1989

- ^ Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

- ^ "(In the Milindapanha) Menander is declared an arhat", McEvilley, p. 378.

- ^ Simmons, Caleb; Sarao, K. T. S. (2010). "Pushyamitra Sunga, a Hindu ruler in the second century BCE, was a great persecutor of Buddhists". In Danver, Steven L. Popular Controversies in World History. ABC-CLIO. p. 89. ISBN 978-1598840780

- ^ Myer, Prudence R. (1986). "Bodhisattvas and Buddhas: Early Buddhist Images from Mathurā". Artibus Asiae. 47 (2): 111–113. doi:10.2307/3249969. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249969.

- ^ Miller, Derek (2018). The Silk Road. Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 66.

- ^ Sørensen, Henrik H. (1995). "Buddhist Sculptures from the Song Dynasty at Mingshan Temple in Anyue, Sichuan". Artibus Asiae. 55 (3/4): 281–302. doi:10.2307/3249752. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249752.

- ^ Solonin, K. J. (2013). "Buddhist Connections between the Liao and Xixia: Preliminary Considerations". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 43: 171–219. ISSN 1059-3152. JSTOR 43855194.

- ^ Lin, Hang (1 May 2019). "A Sinicised Religion Under Foreign Rule: Buddhism in the Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115–1234)". The Medieval History Journal. 22 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1177/0971945818806991. ISSN 0971-9458. S2CID 165514947.

- ^ Cotterell, A; The imperial capitals of China: an inside view of the celestial empire, Random House 2008, ISBN 978-1-84595-010-1 p. 179

- ^ Ortiz, Valérie Malenfer; Dreaming the southern song landscape: the power of illusion in Chinese painting, Brill 1999, ISBN 978-90-04-11011-3 pp. 161–162

- ^ Cahill, James (1997). "Continuations of Ch'an Ink Painting into Ming-Ch'ing and the Prevalence of Type Images". Archives of Asian Art. 50: 17–41. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111272.

- ^ Ryor, Kathleen M. (2019). "Style as Substance: Literary Ink Painting and Buddhist Practice in Late Ming Dynasty China". In Faini, Marco; Meneghin, Alessia (eds.). Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. Intersections 59. Vol. 59. Brill. pp. 244–266. ISBN 978-90-04-34254-5. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvrzgvxg.19.

- ^ Ursula., Toyka-Fuong (2014). The splendours of paradise murals and epigraphic documents at the early Ming Buddhist monastery Fahai Si. Institut Monumenta Serica. ISBN 978-3-8050-0617-0. OCLC 1087831059.

- ^ Weidner, Marsha Smith, and Patricia Ann Berger. Latter Days of the Law : Images of Chinese Buddhism, 850–1850. Lawrence, KS: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1994.

- ^ Berger 1994, p. 113

- ^ Berger 1994, pp. 114–118

- ^ Berger 1994, p. 114

- ^ Berger, Patricia Ann. Empire of Emptiness : Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2003.

- ^ "Crown". Arts of Korea. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Grayson (2002), p. 21.

- ^ a b Grayson (2002), p. 25.

- ^ Grayson (2002), p. 24.

- ^ Peter N. Stearns & William Leonard Langer (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.; "Korea, 500–1000 A.D." Timeline of Arts History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Grayson (2002), pp. 27 & 33.

- ^ "Korean Buddhist Sculpture, 5th–9th Century". Timeline of Arts History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ "Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "Japanese Art and Its Korean Secret". www2.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Fletcher, B.; Cruickshank, D. (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture. Architectural Press. p. 716. ISBN 978-0750622677. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ metmuseum.org

- ^ Grayson, J.H. (2002). Korea: A Religious History. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 33. ISBN 978-0700716050. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Sampa Biswas (2010). Indian Influence on the Art of Japan. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-8172112691.

- ^ Kotobank, Jōchō. The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ Kotobank, Kei school. The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ Kotobank, Sanjūsangen-dō. The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ Buddhist Statues at the Sanjūsangen-dō. Sanjūsangen-dō.

- ^ Deborah E. Klimburg-Salter; Christian Luczanits (1997). Tabo: a lamp for the kingdom : early Indo Tibetan Buddhist art in the western Himalaya, Archeologia, arte primitiva e orientale. Skira. ISBN 9788881182091.

- ^ a b T. Richard Blurton (1994), Hindu Art, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674391895, pp. 202–204, Quote: "Buddhism flourished in this part of India throughout the first millennium AD, especially under the patronage of Pala kings of the eighth and twelfth centuries. Towards the end of this period, popular Buddhism and Hinduism became increasingly intermeshed. However, when Muslim invaders from further west sacked the monasteries in the twelfth century, Buddhism collapsed as a major force in India."

- ^ von Schroeder, Ulrich. 1990. Buddhist Sculptures of Sri Lanka. First comprehensive monograph on the stylistic and iconographic development of the Buddhist sculptures of Sri Lanka. 752 pages with 1620 illustrations (20 colour and 1445 half-tone illustrations; 144 drawings and 5 maps. (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd.). von Schroeder, Ulrich. 1992. The Golden Age of Sculpture in Sri Lanka – Masterpieces of Buddhist and Hindu Bronzes from Museums in Sri Lanka, [catalogue of the exhibition held at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, D.C., 1 November 1992 – 26 September 1993]. (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd.).

- ^ "The Post Pagan Period – Part 1". seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "The Post Pagan Period – Part 3". seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "buddhaartgallery.com". buddhaartgallery.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "buddhaartgallery.com". buddhaartgallery.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ W. Vivian De Thabrew (2014). Buddhist Monuments and Temples of Cambodia and Laos. Author House. p. 33. ISBN 978-1496998972.

- ^ a b c Dawn F. Rooney (2016). Thai Buddhist Art: Discover Thai Art. River Books. ISBN 978-6167339696.

- ^ a b c Jean Philippe Vogel; Adriaan Jacob Barnouw (1936). Buddhist Art in India, Ceylon, and Java. Asian Educational Services. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-8120612259.

- ^ John Miksic (2012). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1462909100.

- ^ "Prajnaparamita". Virtual Collections of Asian Masterpieces. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Orlina, Roderick (2012). "Epigraphical evidence for the cult of Mahāpratisarā in the Philippines". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 35 (1–2): 165–166. ISSN 0193-600X. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

This image was previously thought to be a distorted Tārā, but was recently correctly identified as a Vajralāsyā ('Bodhisattva of amorous dance'), one of the four deities associated with providing offerings to the Buddha Vairocana and located in the southeast corner of a Vajradhātumaṇḍala.

- ^ Weinstein, John. "Agusan Gold Vajralasya". Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019.

Scholars think that the statue may represent an offering goddess from a three-dimensional Vajradhatu (Diamond World) mandala.

- ^ Peralta, Jesus T. (July–August 1983). "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments From the Central Bank of the Philippines". Arts of Asia. pp. 54–60.

- ^ Zafra, Jessica (26 April 2008). "Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors'". Newsweek. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Legeza, Laszlo (1988). "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art". Arts of Asia. Vol. 18, no. 4. pp. 129–133.

- ^ "History of Palawan". Camperspoint. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". Buddhism in the Philippines. 8 November 2014.

- ^ "Garum Masala;Dramatic archaeological discoveries have led scholars to radically reassess the size and importance of the trade between ancient Rome and India". New York Review. 20 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Magazine, Smithsonian; Parker, Christopher. "Archaeologists Unearth Buddha Statue in Ancient Egyptian Port City". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Jarus, Owen (2 May 2023). "1st-century Buddha statue from ancient Egypt indicates Buddhists lived there in Roman times". livescience.com.

- ^ a b "Buddha statue found in ancient Egyptian seaport, points to Roman-era links with India". ABC News. 28 April 2023.

- ^ Carannante, Alfredo; Ast, Rodney; Kaper, Olaf; Tomber, Roberta (1 January 2020). "Berenike 2019: Report on the Excavations". Thetis.

Some of the stone sculpture, both relief and in the round, included images of Buddha and other South Asian deities. (...) The second item was a small stone head of Buddha measuring 9.3 cm high. Its hair was drawn back from the front and sides in wavy strands. The topknot was unusually flat, but clearly marked by a ribbon surrounding it, both typical elements of Buddha heads. The ears, which would have to be characterized by long earlobes, were not represented, but were probably painted on slightly protruding surfaces (Pl. XXIII 1, 2 and 4). An artisan at Berenike had produced it from local gypsum. According to its overall appearance this iconography seems to be Gandharan, Kushan or Guptan.

- ^ Kaper, O.E (2021). "Berenike as a Harbour for Meroe: New evidence for Meroitic presence on the Red Sea Coast". Der Antike Sudan. Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin E.v. 32: 58.

- ^ Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, University of California Press, 2004

- ^ ARTlines, April 1983

- ^ The Brooklyn Rail, December 2007

- ^ a poster advertising one of the events is archived here – http://www.nbo.org.uk/whats%20on/poster.pdf Archived 24 August 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lokabandhu. "Triratna Buddhist Community News: Report from 'Buddha Mind – Creative Mind?' conference". fwbo-news.blogspot.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "Dharma Arts Network – Launched at Buddha Mind – Creative Mind ?". dharmaarts.ning.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

General and cited references

- Gibson, Agnes C.; Jas. Burgess (1901). Buddhist Art in India (Revised and Enlarged ed.). London: Bernard Quaritch. Tr. from the 'Handbook' of Prof. Albert Grunwedel.

- Grayson, James Huntley (2002). Korea: A Religious History. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1605-X.

- von Schroeder, Ulrich (1990). Buddhist Sculptures of Sri Lanka. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications. ISBN 962-7049-05-0. (752 p.; 1620 illustrations.)

- von Schroeder, Ulrich (1992). The Golden Age of Sculpture in Sri Lanka: Masterpieces of Buddhist and Hindu Bronzes from Museums in Sri Lanka. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications. ISBN 9789627049067. OCLC 27648216. Catalogue of the exhibition held at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, D.C., 1 November 1992 – 26 September 1993.

Further reading

- Foltz, Richard C. (2010). Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1.

- D. G. Godse's writings in Marathi.[full citation needed]

- Jarrige, Jean-François (2001). Arts asiatiques- Guimet. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux : Guimet, Musée national des arts asiatiques. ISBN 2-7118-3897-8.

- Kossak, S.M.; et al. (1998). Sacred visions: early paintings from central Tibet. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870998614.

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1982. ISBN 978-0870993008.

- Arts of Korea. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1998. ISBN 0870998501.[dead link]

- Lee, Sherman (2003). A History of Far Eastern Art (5th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-183366-9.

- Leidy, Denise Patry & Strahan, Donna (2010). Wisdom embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1588393999.

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870993747.

- Scarre, Chris, ed. (1991). Past Worlds: The Times Atlas of Archeology. London: Times Books Limited. ISBN 0-7230-0306-8.

- Huntington, Susan L. (Winter 1990). "Early Buddhist Art and the Theory of Aniconism". Art Journal. 9 (4: New Approaches to South Asian Art): 401–408. doi:10.2307/777142. JSTOR 777142.

- von Schroeder, Ulrich (1981). Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd.

- von Schroeder, Ulrich (2001). Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd.

- Watt, James C. Y.; et al. (2004). China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391264.

External links

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum (archived 30 January 2010)

![Mathura school Buddha, Northern Satraps, end of 1st century CE[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Inscribed_Seated_Buddha_Image_in_Abhaya_Mudra_-_Kushan_Period_-_Katra_Keshav_Dev_-_ACCN_A-1_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_5972.JPG/133px-Inscribed_Seated_Buddha_Image_in_Abhaya_Mudra_-_Kushan_Period_-_Katra_Keshav_Dev_-_ACCN_A-1_-_Government_Museum_-_Mathura_2013-02-24_5972.JPG)