The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

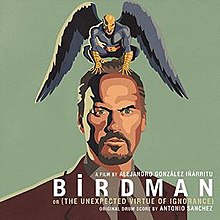

| Birdman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | October 14, 2014 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack, stage & screen | |||

| Length | 1:17:58 | |||

| Label | Milan Records M2-36689 | |||

| Producer | various | |||

| Antonio Sánchez chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

Birdman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) is the soundtrack for the 2014 film Birdman. It includes solo jazz percussion throughout the film and extended segments of classical music taken from various composers including Mahler, Ravel, Rachmaninov, and John Adams. Several jazz compositions by Victor Hernández Stumpfhauser and Joan Valent also offset the original music composition by Antonio Sánchez. The soundtrack was released as a CD (77 min) on October 14, 2014, and as an LP (69 min) on April 7, 2015.[2] It won the Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media.

Development

The film's original music segments consist of solo jazz percussion performances alongside a number of well known classical music pieces. With Mahler and Tchaikovsky among others, most of the composers featured are part of the standard classical repertoire, but Iñárritu did not regard the choice of pieces as important, saying "I think all those classical pieces are, in a way, great, but honestly if I would have put (in) another good classical piece it would be the same film".[3] Nonetheless, the choice of classical music pieces was strongly oriented to highly melodic scores taken predominantly from the 19th and 20th century classical repertoire (Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Ravel). Iñárritu stated that the classical components come from the world of the play, citing the radio in Riggan's room and the show itself as two sources of the music.[4] The drum sections comprise the majority of the score however, and were composed by Antonio Sánchez. Iñárritu explained the choice by saying they helped to structure scenes, and that "The drums, for me, was a great way to find the rhythm of the film... In comedy, rhythm is king, and not having the tools of editing to determine time and space, I knew I needed something to help me find the internal rhythm of the film."[5] He also wanted a score that "wouldn't cater to an audience's expectations", which the drums, being more abstract, provided.[6] The official soundtrack was released on October 14, 2014.[7]

Iñárritu contacted friend and jazz drummer Antonio Sánchez in January 2013, inviting him to compose the score for the film.[8] His reaction to writing a soundtrack using only drums was similar to Lubezki's thoughts of shooting the movie like a single shot: "It was a scary proposition because I had no point of reference of how to achieve this. There's no other movie I know that has a score like this."[9] Sánchez had also not worked on a film before,[8] nevertheless, after receiving the script, composed "rhythmic themes" for each of the characters.[10] Iñárritu was looking for the opposite approach however, preferring spontaneity and improvisation.[11] Sánchez then waited until production moved to New York before composing more,[10] where he visited the set for a couple of days to get a better idea of the film.[11] Following this, a week before principal photography, he and Iñárritu went to a studio to record some demos.[4][12] During these sessions the director would first talk him through the scene, then while Sánchez was improvising guide him by raising his hand to indicate an event – such as a character opening a door – or by describing the rhythm with verbal sounds.[12][13] They recorded around seventy demos,[10] which Iñárritu used to inform the pacing of the scenes on set,[14] and once filming was complete, spliced them into the rough cut.[12] Sánchez summarized the process by saying "The movie fed on the drums and the drums fed on the imagery."[11]

His next work on Birdman was in September, where he traveled to Los Angeles to re-record the soundtrack.[8] By this stage the film was assembled, so during the two days of recording Sánchez would watch a scene to see what Iñárritu had done with the demos, then redo the track.[15] This was a new experience for Sánchez who until this point, had guided his improvisations in response to "the sound and energy" around him. Here, he was using a scene to guide him, and said the biggest challenge of the soundtrack was "adapting what I do to a moving image, a story line, and dialogue."[16] As in New York, Iñárritu supervised these recordings, but this time would give specific directions. For example, instructing Sánchez to stop or start when Riggan uttered certain words.[11] Iñárritu also shaped the overall feel of the soundtrack. He wanted it to grow crazier throughout the film, so for the end tracks Sánchez would overdub up to four drum tracks on top of each other.[12][13] Additionally, Iñárritu was not satisfied with the quality of the sound from the previous recordings: it was too good. Instead, he wanted an instrument that sounded like it had not been played in years, to tie in with state of the theatre in the film.[11] To achieve this, Sánchez adjusted his setup; detuning the drums and stacking different kinds of cymbals on top of one another were among the techniques he used.[10][15] Amusingly, this process was included in the film – the first sound in Birdman is in fact Sánchez asking Iñárritu a question in Spanish, followed by his detuning of the drums.[10]

In between the two studio recordings, Sánchez was touring with the Pat Metheny Group..[17] Iñárritu wanted to include a drummer in the film from the beginning,[9] saying "I wanted [Sánchez] to become a character in his own film, and have the play become a play of a play."[4] The drummer recommended his friend Nate Smith, but did not decide on the music to play beforehand, resulting in Smith improvising during the shoots. This meant Sánchez had to learn and match him exactly during the recordings in Los Angeles,[9] noting "Alejandro was very specific and he would watch the clip over and over again to make sure that you could not tell that it was not him that was actually producing the sound. Never in my life have I had to do that."[13] The process was not aided by a different method of recording for the scene outside of St. James Theatre featuring Smith. The drums were moved out onto the street, and people carrying mics a block away would walk towards and past Sánchez as he was playing, to coordinate the sound and image of the film without the need for post-production effects.[12]

Best Original Score disqualification

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences did not include Birdman on its longlist for the Academy Award for Best Original Score. Sánchez had received a note from the award committee a day earlier explaining the decision, quoting rule fifteen of the 87th Academy Award Rules and writing they felt "the fact that the film also contains over a half an hour of non-original (mostly classical) music cues that are featured very prominently in numerous pivotal moments in the film made it difficult for the committee to accept your submission". Sánchez decided to launch an appeal, and along with Iñárritu and the executive vice-president of Fox Music, sent letters to the chair of the Academy's music branch executive committee, Charles Fox, asking that the committee reconsider their decision.[18] One of the points raised was that the committee had incorrectly calculated the ratio of classical to original music, which after being clarified Sánchez thought he was "on really solid ground".[19] A response from Fox on December 19 however, explained that a special meeting of the music committee was held, and although its members had "great respect" for the score and considered it "superb", they thought that the classical music "was also used as scoring", "equally contributes to the effectiveness of the film", and that the musical identity of the film was created by both the drums and classical music. Ultimately, they did not overturn their decision.[18] Sánchez said that he and Iñárritu were not satisfied with the explanation, and that "to not be able to even participate, to not be on the list, that's what's so disappointing".[19]

Soundtrack

Below, per the Academy Awards committee, is the list of classical music used in the film as well as several jazz pieces by composers other than Antonio Sánchez. The Academy Awards committee disqualified the film from competing for the Best Original Soundtrack award. The actual ASCAP version of the released CD soundtrack grouped the solo jazz percussion pieces at the start of the disc followed by four or five of the classical music selections grouped together at the end of the soundtrack disc.

- Birdman Blind Melody; composed by Joan Valent

- BeBirdman; composed by Joan Valent

- Harpad; composed by Victor Hernández Stumpfhauser

- BB Drum Beats; composed by Brian Blade

- Pavane pour une infante défunte; composed by Maurice Ravel; performed by Orchestre National de Lyon; courtesy of Naxos of America

- Symphony No. 9 in D; composed by Gustav Mahler; performed by Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; courtesy of Naxos of America

- Jazz Bar Music; written and performed by Victor Hernández Stumpfhauser

- Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 – "Andante cantabile"; composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky; arranged and performed by Stefano Seghedoni; courtesy of Chicago Music Library

- Dream Team; written by Jeff Bernat and Joel Cowell; performed by Jeff Bernat; courtesy of Tunecore

- "Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen" (Rückert-Lieder); composed by Gustav Mahler; performed by Violeta Urmana, Vienna Philharmonic and Pierre Boulez; courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon, Hamburg; under license from Universal Music Enterprises

- Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 – "Andantino in modo di canzona"; composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky; performed by RSO Ljubljana and Anton Nanut; courtesy of The Savoy Label Group/Selectracks

- "Passacaille (Très large)" from Piano Trio in A minor; composed by Maurice Ravel; performed by Victor Hernández Stumpfhauser

- "Passacaille (Très large)" from Piano Trio in A minor; composed by Maurice Ravel; performed by Beaux Arts Trio; courtesy of Decca Music Group; under license from Universal Music Enterprises

- "Chorus of Exiled Palestinians" from The Death of Klinghoffer; composed by John Adams; libretto by Alice Goodman; performed by the orchestra of the Opéra National de Lyon, conducted by Kent Nagano; the London Opera Chorus, directed by Richard Cooke; courtesy of Nonesuch Records; by arrangement with Warner Music Group Film & TV Licensing

- Harmonium: "III. Wild Nights"; composed by John Adams; performed by the San Francisco Symphony & Chorus, conducted by John Adams; courtesy of Nonesuch Records; by arrangement with Warner Music Group Film & TV Licensing

- Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 (Largo – Allegro moderato); composed by Sergei Rachmaninoff; performed by Neville Marriner, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; courtesy of Naxos of America

References

- ^ Review at AllMusic. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Birdman Soundtrack, 2014, retrieved 16 September 2015

- ^ Hammond, Pete (December 22, 2014). "Birdman Score Drummed out of Oscars as Academy Rejects Filmmaker's Appeal". Deadline. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Anne (January 12, 2015). "Watch: Why Golden Globe Winner Alejandro González Iñárritu Took Risks on Birdman". Thompson on Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (October 13, 2014). "Watch: How Birdman Composer Antonio Sanchez Drummed the Score". Thompson on Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (January 28, 2015). "Drummer-composer Antonio Sanchez talks Birdman". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Birdman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Amazon. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c Malone, Tyler (Winter 2014). "(The Unexpected Virtue Of A Jazz Drummer)". PMc Publishing. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c Ciafardini, Marc (November 24, 2014). "Interview…Composer Antonio Sanchez on the Drums and Jazzy Ambiguity of Birdman". goseetalk. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Panosian, Diane (December 3, 2014). "Awards 2015 Spotlight: Composer Antonio Sanchez Takes SSN into the Jam Sessions that Created Birdman's Dauntless Percussion Score". SSN Insider. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Patches, Matt (November 4, 2014). "How Alejandro G. Iñárritu 'directed' drummer Antonio Sanchez's Birdman' score". HitFix. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e de Larios, Margaret (October 17, 2014). "Birdman's Beating Heart: An Interview with Composer Antonio Sanchez". the Film Experience. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c Moulton, Jack (December 3, 2014). "Interview: Drummer Antonio Sanchez on his first film composition Birdman". The Awards Circuit. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (December 20, 2014). "Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki details the 'dance' of filming Birdman". HitFix. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Martinez, Kiko (October 31, 2014). "Antonio Sanchez – Birdman". Cinesnob.net. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Mahoney, Lesley (November 5, 2014). "Antonio Sanchez '97: The Making of the Birdman Score". Berklee College of Music. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Ali, Lorraine (December 9, 2014). "Antonio Sanchez's soaring beat takes flight in Birdman". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Feinberg, Scott (December 24, 2014). "The Inside Story: Why Birdman's Drum Score Isn't Eligible for an Oscar and Why an Appeal Was Rejected". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Patches, Matt (December 22, 2014). "Exclusive: Birdman composer says Oscar DQ doesn't make mathematical sense". HitFix. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.