The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

| Baltic | |

|---|---|

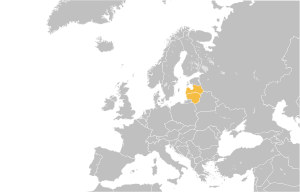

| Geographic distribution | Northern Europe, historically also Eastern Europe and Central Europe |

| Ethnicity | Balts |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Baltic |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | bat |

| Linguasphere | 54= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | None east2280 (East Baltic) prus1238 (Old Prussian) |

Countries where an East Baltic language is the national language | |

The Baltic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively or as a second language by a population of about 6.5–7.0 million people[1][2] mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Europe. Together with the Slavic languages, they form the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European family.

Scholars usually regard them as a single subgroup divided into two branches: West Baltic (containing only extinct languages) and East Baltic (containing at least two living languages, Lithuanian, Latvian, and by some counts including Latgalian and Samogitian as separate languages rather than dialects of those two). The range of the East Baltic linguistic influence once possibly reached as far as the Ural Mountains, but this hypothesis has been questioned.[3][4][5]

Old Prussian, a Western Baltic language that became extinct in the 18th century, had possibly conserved the greatest number of properties from Proto-Baltic.[6]

Although related, Lithuanian, Latvian, and particularly Old Prussian have lexicons that differ substantially from one another and so the languages are not mutually intelligible. Relatively low mutual interaction for neighbouring languages historically led to gradual erosion of mutual intelligibility, and development of their respective linguistic innovations that did not exist in shared Proto-Baltic. The substantial number of false friends and various uses and sources of loanwords from their surrounding languages are considered to be the major reasons for poor mutual intelligibility today.

Branches

Within Indo-European, the Baltic languages are generally classified as forming a single family with two branches: Eastern and Western Baltic. But these two branches are sometimes classified as independent branches of Balto-Slavic itself.[7]

| East Baltic | |

|---|---|

| Latvian | c. 1.5 million[8] |

| Latgalian* | 150,000–200,000 |

| Lithuanian | c. 4 million |

| Samogitian* | 500,000 |

| Selonian† | Extinct since 16th century |

| Semigallian† | Extinct since 16th century |

| Old Curonian† | Extinct since 16th century |

| West Baltic | |

| Western Galindian† | Extinct since 14th century |

| Old Prussian† | Extinct since early 18th century |

| Skalvian† | Extinct since 16th century |

| Sudovian† | Extinct since 17th century |

| Dnieper Baltic[9] | |

| Eastern Galindian† | Extinct since 12th century[10] |

| Italics indicate disputed classification. | |

| * indicates languages sometimes considered to be dialects. | |

| † indicates extinct languages. | |

History

It is believed that the Baltic languages are among the most conservative of the currently remaining Indo-European languages,[11][12] despite their late attestation.

Although the Baltic Aesti tribe was mentioned by ancient historians such as Tacitus as early as 98 CE,[13] the first attestation of a Baltic language was c. 1369, in a Basel epigram of two lines written in Old Prussian. Lithuanian was first attested in a printed book, which is a Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas published in 1547. Latvian appeared in a printed Catechism in 1585.[14]

One reason for the late attestation is that the Baltic peoples resisted Christianization longer than any other Europeans, which delayed the introduction of writing and isolated their languages from outside influence.[citation needed]

With the establishment of a German state in Prussia, and the mass influx of Germanic (and to a lesser degree Slavic-speaking) settlers, the Prussians began to be assimilated, and by the end of the 17th century, the Prussian language had become extinct.

After the Partitions of Poland, most of the Baltic lands were under the rule of the Russian Empire, where the native languages or alphabets were sometimes prohibited from being written down or used publicly in a Russification effort (see Lithuanian press ban for the ban in force from 1864 to 1904).[15]

Geographic distribution

Speakers of modern Baltic languages are generally concentrated within the borders of Lithuania and Latvia, and in emigrant communities in the United States, Canada, Australia and the countries within the former borders of the Soviet Union.

Historically the languages were spoken over a larger area: west to the mouth of the Vistula river in present-day Poland, at least as far east as the Dniepr river in present-day Belarus, perhaps even to Moscow, and perhaps as far south as Kyiv. Key evidence of Baltic language presence in these regions is found in hydronyms (names of bodies of water) that are characteristically Baltic.[16][17][18][19][20] The use of hydronyms is generally accepted to determine the extent of a culture's influence, but not the date of such influence.[21]

The eventual expansion of the use of Slavic languages in the south and east, and Germanic languages in the west, reduced the geographic distribution of Baltic languages to a fraction of the area that they formerly covered.[22][23][24] The Russian geneticist Oleg Balanovsky speculated that there is a predominance of the assimilated pre-Slavic substrate in the genetics of East and West Slavic populations, according to him the common genetic structure which contrasts East Slavs and Balts from other populations may suggest that the pre-Slavic substrate of the East Slavs consists most significantly of Baltic-speakers, which predated the Slavs in the cultures of the Eurasian steppe according to archaeological references he cites.[25]

Contact with Uralic languages

Though Estonia is geopolitically included among the Baltic states due to its location, Estonian is a Finnic language of the Uralic language family and is not related to the Baltic languages, which are Indo-European.

The Mordvinic languages, spoken mainly along western tributaries of the Volga, show several dozen loanwords from one or more Baltic languages. These may have been mediated by contacts with the Eastern Balts along the river Oka.[26] In regards to the same geographical location, Asko Parpola, in a 2013 article, suggested that the Baltic presence in this area, dated to c. 200–600 CE, is due to an "elite superstratum".[27] However, linguist Petri Kallio argued that the Volga-Oka is a secondary Baltic-speaking area, expanding from East Baltic, due to a large number of Baltic loanwords in Finnic and Saami.[28]

Finnish scholars also indicate that Latvian had extensive contacts with Livonian,[29] and, to a lesser extent, to Estonian and South Estonian.[30] Therefore, this contact accounts for the number of Finnic hydronyms in Lithuania and Latvia that increase in a northwards direction.[31]

Parpola, in the same article, supposed the existence of a Baltic substratum for Finnic, in Estonia and coastal Finland.[32] In the same vein, Kallio argues for the existence of a lost "North Baltic language" that would account for loanwords during the evolution of the Finnic branch.[33]

Comparative linguistics

Genetic relatedness

The Baltic languages are of particular interest to linguists because they retain many archaic features, which are thought to have been present in the early stages of the Proto-Indo-European language.[3] However, linguists have had a hard time establishing the precise relationship of the Baltic languages to other languages in the Indo-European family.[34] Several of the extinct Baltic languages have a limited or nonexistent written record, their existence being known only from the records of ancient historians and personal or place names. All of the languages in the Baltic group (including the living ones) were first written down relatively late in their probable existence as distinct languages. These two factors combined with others have obscured the history of the Baltic languages, leading to a number of theories regarding their position in the Indo-European family.

The Baltic languages show a close relationship with the Slavic languages, and are grouped with them in a Balto-Slavic family by most scholars.[disputed – discuss][attribution needed] This family is considered to have developed from a common ancestor, Proto-Balto-Slavic. Later on, several lexical, phonological and morphological dialectisms developed, separating the various Balto-Slavic languages from each other.[35][36] Although it is generally agreed that the Slavic languages developed from a single more-or-less unified dialect (Proto-Slavic) that split off from common Balto-Slavic, there is more disagreement about the relationship between the Baltic languages.[37]

The traditional view is that the Balto-Slavic languages split into two branches, Baltic and Slavic, with each branch developing as a single common language (Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic) for some time afterwards. Proto-Baltic is then thought to have split into East Baltic and West Baltic branches. However, more recent scholarship has suggested that there was no unified Proto-Baltic stage, but that Proto-Balto-Slavic split directly into three groups: Slavic, East Baltic and West Baltic.[38][39] Under this view, the Baltic family is paraphyletic, and consists of all Balto-Slavic languages that are not Slavic. In the 1960s Vladimir Toporov and Vyacheslav Ivanov made the following conclusions about the relationship between the Baltic and Slavic languages:[40][41]

- the Proto-Slavic language formed out of peripheral-type Baltic dialects;

- the Slavic linguistic type formed later from the structural model of the Baltic languages;

- the Slavic structural model is a result of the transformation from the Baltic languages structural model.

These scholars' theses do not contradict the close relationship between Baltic and Slavic languages and, from a historical perspective, specify the Baltic-Slavic languages' evolution – the terms 'Baltic' and 'Slavic' are relevant only from the point of view of the present time, meaning diachronic changes, and the oldest stage of the language development could be called both Baltic and Slavic;[40] this concept does not contradict the traditional thesis that the Proto-Slavic and Proto-Baltic languages coexisted for a long time after their formation – between the 2nd millennium BC and circa the 5th century BC – the Proto-Slavic language was a continuum of the Proto-Baltic dialects, more rather, the Proto-Slavic language should have been localized in the peripheral circle of Proto-Baltic dialects.[42]

Finally, a minority of scholars argue that Baltic descended directly from Proto-Indo-European, without an intermediate common Balto-Slavic stage. They argue that the many similarities and shared innovations between Baltic and Slavic are caused by several millennia of contact between the groups, rather than a shared heritage.[43]

Thracian hypothesis

The Baltic-speaking peoples likely encompassed an area in eastern Europe much larger than their modern range. As in the case of the Celtic languages of Western Europe, they were reduced by invasion, extermination and assimilation[citation needed]. Studies in comparative linguistics point to genetic relationship between the languages of the Baltic family and the following extinct languages:

The Baltic classification of Dacian and Thracian has been proposed by the Lithuanian scientist Jonas Basanavičius, who insisted this is the most important work of his life and listed 600 identical words of Balts and Thracians.[51][52] His theory included Phrygian in the related group, but this did not find support and was disapproved among other authors, such as Ivan Duridanov, whose own analysis found Phrygian completely lacking parallels in either Thracian or Baltic languages.[53]

The Bulgarian linguist Ivan Duridanov, who improved the most extensive list of toponyms, in his first publication claimed that Thracian is genetically linked to the Baltic languages[54] and in the next one he made the following classification:

"The Thracian language formed a close group with the Baltic, the Dacian and the "Pelasgian" languages. More distant were its relations with the other Indo-European languages, and especially with Greek, the Italic and Celtic languages, which exhibit only isolated phonetic similarities with Thracian; the Tokharian and the Hittite were also distant. "[53]

Of about 200 reconstructed Thracian words by Duridanov most cognates (138) appear in the Baltic languages, mostly in Lithuanian, followed by Germanic (61), Indo-Aryan (41), Greek (36), Bulgarian (23), Latin (10) and Albanian (8). The cognates of the reconstructed Dacian words in his publication are found mostly in the Baltic languages, followed by Albanian. Parallels have enabled linguists, using the techniques of comparative linguistics, to decipher the meanings of several Dacian and Thracian placenames with, they claim, a high degree of probability. Of 74 Dacian placenames attested in primary sources and considered by Duridanov, a total of 62 have Baltic cognates, most of which were rated "certain" by Duridanov.[55] For a big number of 300 Thracian geographic names most parallels were found between Thracian and Baltic geographic names in the study of Duridanov.[53][56][53] According to him the most important impression make the geographic cognates of Baltic and Thracian

"the similarity of these parallels stretching frequently on the main element and the suffix simultaneously, which makes a strong impression".[56][54]

Romanian linguist Sorin Paliga, analysing and criticizing Harvey Mayer's study, did admit "great likeness" between Thracian, the substrate of Romanian, and "some Baltic forms".[57]

See also

References

- ^ "Lietuviai Pasaulyje" (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos statistikos departamentas. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Latvian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) Standard Latvian language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) Latgalian language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. Ancient peoples and places 33. London: Thames and Hudson. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Mallory, J. P., ed. (1997). "Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture". Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Fitzroy Dearborn.

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2007). [The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Ringe, D.; Warnow, T.; Taylor, A. (2002). "Indo-European and computational cladistics". Transactions of the Philological Society. 100: 59–129. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00091.

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Old Prussian". Glottolog 4.3.

- ^ Valsts valoda

- ^ Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija [Baltic languages. Comparative history] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 61. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ^ "Балтийские языки". lingvarium.org (in Russian). Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Fischer, Beatrice; Jensen, Matilde (2012). Translation and the Reconfiguration of Power Relations: Revisiting Role and Context of Translation and Interpreting. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 120. ISBN 9783643902832.

- ^ Gelumbeckaitė 2018: "... notably East Slavic, which fostered the retention there of features of archaic Indo-European provenience"

- ^ Tacitus. "XLV". Germania.

- ^ Baldi, Philip (2002). The Foundations of Latin. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 34–35. ISBN 3-11-016294-6.

- ^ Vaicekauskas, Mikas. Lithuanian Handwritten Books in the Period of the Ban on the Lithuanian Press (1864–1904) (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Blažek, Vaclav. "Baltic horizon in Eastern Bohemian hydronymy?". In: Tiltai. Priedas. 2003, Nr. 14, p. 14. ISSN 1648-3979.

- ^ Zinkevičius, Zigmas; Luchtanas, Aleksiejus; Česnys, Gintautas (2005). Where We Come from: The Origin of the Lithuanian People. Science & Encyclopedia Publishing Institute. p. 38. ISBN 978-5-420-01572-8.

...the hydronyms in this region [Central Forest Zone] show very uneven traces of a Baltic presence: in some places (mainly in the middle of this area) the stratum of Baltic hydronyms is thick, but elsewhere (especially along the edges of this area) only individual Baltic hydronyms can be found...

- ^ Parpola, A. (2013). "Formation of the Indo-European and Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language families in the light of archaeology" (PDF). In Grünthal, R.; Kallio, P. (eds.). A linguistic map of prehistoric northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. p. 133.

Ancient Baltic hydronyms cover an area that includes the Upper Dnieper area and extends approximately from Kiev and the Dvina to Moscow

- ^ Young, Steven (2017). "Baltic". In Mate Kapović (ed.). The Indo-European Languages (Second ed.). Routledge. p. 486.

The original Baltic-speaking territory was once much larger, extending eastward into the upper Dniepr river basin and beyond.

- ^ Gelumbeckaitė 2018:"The study of hydronyms has shown that the Proto-Baltic area was about six times larger than the ethnic territory of the present-day Balts ..."

- ^ Georgiev, Vladimir I. (31 December 1972). "The Earliest Ethnological Situation of the Balkan Peninsula as Evidenced by Linguistic and Onomastic Data". Aspects of the Balkans: Continuity and Change. De Gruyter. pp. 50–65. doi:10.1515/9783110885934-003. ISBN 978-3-11-088593-4.

Information about the ethnic identity of the older tribes that had lived in a given territory can be obtained only from toponymy and particularly from hydronymy. Hydronyms, especially the names of large rivers, are very resistant to changes of the population and they may supply us with information about the older population of a particular region

- ^ Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture. Blackwell Publishing. p. 378. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7.

Baltic river names are found across a large swath of now Slavic-speaking territory in eastern Europe and present-day Russia, as far east as Moscow and as far south as Kiev.

- ^ Andersen, Henning (31 December 1996). Reconstructing Prehistorical Dialects: Initial Vowels in Slavic and Baltic. DE GRUYTER MOUTON. p. 43. doi:10.1515/9783110819717. ISBN 978-3-11-014705-6.

[... the southeast, in present-day Belarus] is territory which was formerly Baltic speaking, but in which Baltic yielded to Slavic in the period from the 400s to the 1000s — in part through a displacement of Lithuanian speakers towards the northwest [...] This gradual process of language replacement is documented by the more than 2000 Baltic place names (mostly hydronyms) taken over from the Balts by the Slavs in Belarus, for not only does a continuity in toponyms in general attest to a gradual process of ethno-cultural reorientation ...

- ^ Timberlake, Alan (2014). "The Simple Sentence / Der einfache Satz". In Karl Gutschmidt; Tilman Berger; Sebastian Kempgen; Peter Kosta (eds.). Die slavischen Sprachen [The Slavic Languages]. Vol. Halbband 2. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. p. 1665. doi:10.1515/9783110215472.1675.

Baltic hydronyms are attested from the Pripjať basin northwards, so that it is clear that there were Balts inbetween the homeland of the Slavs in the Ukrainian mesopotamia (between the Dnepr and the Dnester) and the Finnic areas of the north.

- ^ П, Балановский О. (30 November 2015). Генофонд Европы [Gene pool of Europe] (in Russian). KMK Scientific Press. ISBN 9785990715707.

Прежде всего, это преобладание в славянских популяциях дославянского субстрата – двух ассимилированных ими генетических компонентов – восточноевропейского для западных и восточных славян и южноевропейского для южных славян... Можно с осторожностью предположить, что ассимилированный субстрат мог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указывают на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтский субстрату славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные нами генетические данные – и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома – указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетически ми соседями восточных славян. При этом балты являются и лингвистически ближайшими родственниками славян. И можно полагать, что к моменту ассимиляции их генофонд не так сильно отличался от генофонда начавших свое широкое расселение славян. Поэтому если предположить, что расселяющиеся на восток славяне ассимилировали по преимуществу балтов, это может объяснить и сходство современных славянских и балтских народов друг с другом, и их отличия от окружающих их не балто-славянских групп Европы... В работе высказывается осторожное предположение, что ассимилированный субстрат мог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указывают на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтский субстрат у славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные в этой работе генетические данные – и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома – указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетическими соседями восточных славян.

[First of all, this is the predominance of the pre-Slavic substrate in the Slavic populations – the two genetic components assimilated by them – the Eastern European for the Western and Eastern Slavs and the South European for the Southern Slavs ... It can be assumed with caution that the assimilated substrate could be represented mainly by the Baltic-speaking populations. Indeed, archaeological data indicate a very wide distribution of the Baltic groups before the beginning of the settlement of the Slavs. The Baltic substratum of the Slavs (true, along with the Finno-Ugric) was also identified by anthropologists. The genetic data we obtained – both on the graphs of genetic relationships and on the share of common genome fragments – indicate that the modern Baltic peoples are the closest genetic neighbors of the Eastern Slavs. Moreover, the Balts are also linguistically the closest relatives of the Slavs. And it can be assumed that by the time of assimilation, their gene pool was not so different from the gene pool of the Slavs who began their widespread settlement. Therefore, if we assume that the Slavs settling in the east assimilated mainly the Balts, this can explain the similarity of the modern Slavic and Baltic peoples with each other, and their differences from the surrounding non-Balto-Slavic groups of Europe ... the assimilated substrate could be represented mainly by the Baltic-speaking populations. Indeed, archaeological data indicate a very wide distribution of the Baltic groups before the beginning of the settlement of the Slavs. Anthropologists have also identified the Baltic substrate among the Slavs (although, along with the Finno-Ugric). The genetic data obtained in this work – both on the graphs of genetic relationships and on the share of common fragments of the genome – indicate that the modern Baltic peoples are the closest genetic neighbors of the Eastern Slavs.] - ^ Grünthal, Riho (2012). "Baltic loanwords in Mordvin" (PDF). A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia 266. pp. 297–343. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Parpola, A. (2013). "Formation of the Indo-European and Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language families in the light of archaeology". In: Grünthal, R. & Kallio, P. (Eds.). A linguistic map of prehistoric northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura, 2013. p. 150.

- ^ Kallio, Petri. "The Language Contact Situation in Prehistoric Northeastern Europe". In: Robert Mailhammer, Theo Vennemann gen. Nierfeld, and Birgit Anette Olsen (eds.). The Linguistic Roots of Europe: Origin and Development of European Languages. Copenhagen Studies in Indo-European 6. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2015. p. 79.

- ^ Grünthal, Riho [in Finnish] (2015). "Livonian at the crossroads of language contacts". In Santeri Junttila (ed.). Contacts between the Baltic and Finnic languages. Vol. 7. Helsinki: Uralica Helsingiensia. pp. 97–102. ISBN 978-952-5667-67-7. ISSN 1797-3945.

- ^ Junttila, Santeri (2015). "Introduction". In Santeri Junttila (ed.). Contacts between the Baltic and Finnic languages. Vol. 7. Helsinki: Uralica Helsingiensia. p. 6. ISBN 978-952-5667-67-7. ISSN 1797-3945.

- ^ Zinkevičius, Zigmas; Luchtanas, Aleksiejus; Česnys, Gintautas (2005). Where We Come from: The Origin of the Lithuanian People. Science & Encyclopedia Publishing Institute. p. 42. ISBN 978-5-420-01572-8.

- ^ Parpola, A. (2013). "Formation of the Indo-European and Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language families in the light of archaeology". In: Grünthal, R. & Kallio, P. (Eds.). A linguistic map of prehistoric northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura, 2013. p. 133.

- ^ Kallio, Petri (2015). "The Language Contact Situation in Prehistoric Northeastern Europe". In Robert Mailhammer; Theo Vennemann gen. Nierfeld; Birgit Anette Olsen (eds.). The Linguistic Roots of Europe: Origin and Development of European Languages. Copenhagen Studies in Indo-European. Vol. 6. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 88–90.

- ^ Senn, Alfred (1966). "The Relationships of Baltic and Slavic". In Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan (eds.). Ancient Indo-European Dialects. University of California Press. pp. 139–151. GGKEY:JUG4225Y4H2. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Mallory, J. P. (1 April 1991). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Hill, Eugen (2016). "Phonological evidence for a Proto-Baltic stage in the evolution of East and West Baltic". International Journal of Diachronic Linguistics and Linguistic Reconstruction. 13: 205–232.

- ^ Kortlandt, Frederik (2009), Baltica & Balto-Slavica, p. 5,

Though Prussian is undoubtedly closer to the East Baltic languages than to Slavic, the characteristic features of the Baltic languages seem to be either retentions or results of parallel development and cultural interaction. Thus I assume that Balto-Slavic split into three identifiable branches, each of which followed its own course of development.

- ^ Derksen, Rick (2008), Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, p. 20,

I am not convinced that it is justified to reconstruct a Proto-Baltic stage. The term Proto-Baltic is used for convenience's sake.

- ^ a b Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija [Baltic languages. Comparative history] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 143. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ^ Бирнбаум Х. О двух направлениях в языковом развитии // Вопросы языкознания, 1985, No. 2, стр. 36

- ^ Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija [Baltic languages. Comparative history] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 144. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ^ Hock, Hans Henrich; Joseph, Brian D. (1996). Language history, language change, and language relationship: an introduction to historical and comparative linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-11-014784-1. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ a b Mayer 1996, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Duridanov 1969, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b de Rosales, Jurate (2015). Europos šaknys [European Roots] (in Lithuanian). Versmė. ISBN 9786098148169.

- ^ de Rosales, Jurate (2020). Las raíces de Europa [The races of Europe] (in Spanish). Kalathos Ediciones. ISBN 9788412186147.

- ^ Schall H. "Sudbalten und Daker. Vater der Lettoslawen". In: Primus congressus studiorum thracicorum. Thracia II. Serdicae, 1974, pp. 304, 308, 310.

- ^ a b Radulescu M. The Indo-European position of lllirian, Daco-Mysian and Thracian: a historic Methodological Approach. 1987. [page needed]

- ^ Dras. J. Basanavičius. Apie trakų prygų tautystę ir jų atsikėlimą Lietuvon. [page needed]

- ^ Balts and Goths: the missing link in European history. Vydūnas Youth Fund. 2004.

- ^ Daskalov, Roumen; Vezenkov, Alexander (13 March 2015). Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Three: Shared Pasts, Disputed Legacies. BRILL. ISBN 9789004290365.

- ^ a b c d Duridanov 1976.

- ^ a b Duridanov 1969.

- ^ Duridanov 1969, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Duridanov 1985.

- ^ Paliga, Sorin. "Tracii şi dacii erau nişte „baltoizi”?" [Were Thracians and Dacians ‘Baltoidic’?]. In: Romanoslavica XLVIII, nr. 3 (2012): 149–150.

Bibliography

- "Lithuania 1863–1893: Tsarist Russification and the Beginnings of the Modern Lithuanian National Movement – Strazas". www.lituanus.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Lituanus Linguistics Index (1955–2004)". Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. provides a number of articles on modern and archaic Baltic languages

- Duridanov, I. (1969). Die Thrakisch- und Dakisch-Baltischen Sprachbeziehungen.

- Duridanov, I. (1976). Ezikyt na Trakite.

- Duridanov, Ivan (1985). Die Sprache der Thraker. Bulgarische Sammlung (in German). Vol. 5. Hieronymus Verlag. ISBN 3-88893-031-6.

- Fraenkel, Ernst (1950). Die baltischen Sprachen. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- Girininkas, Algirdas (1994). "The monuments of the Stone Age in the historical Baltic region". Baltų archeologija (1). English summary, p. 22. ISSN 1392-0189.

- Girininkas, Algirdas (1994). "Origin of the Baltic culture. Summary". Baltų kultūros ištakos. Vilnius: Savastis. p. 259. ISBN 9986-420-00-8.

- Gelumbeckaitė, Jolanta (2018). "The evolution of Baltic". In Jared Klein; Brian Joseph; Matthias Fritz (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. p. 1712-15. doi:10.1515/9783110542431-014.

- Larsson, Jenny Helena; Bukelskytė-Čepelė, Kristina (2018). "The documentation of Baltic". In Jared Klein; Brian Joseph; Matthias Fritz (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1622–1639. doi:10.1515/9783110542431-008.

- Mallory, J. P. (1991). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mayer, H.E. (1992). "Dacian and Thracian as southern Baltoidic". Lituanus. 38 (2). Defense Language Institute, United States Department of Defense. ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Mayer, H.E. (1996). "SOUTH BALTIC". Lituanus. 42 (2). Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Mayer, H.E. (1997). "BALTS AND CARPATHIANS". Lituanus. 43 (2). Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- Pashka, Joseph (1950). Proto Baltic and Baltic languages.

- Remys, Edmund (17 December 2007). "General distinguishing features of various lndo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian". Indogermanische Forschungen. 112 (2007): 244–276. doi:10.1515/9783110192858.1.244. ISSN 1613-0405.

- Mayer, H.E. (1999). "Dr. Harvey E. Mayer, February 1999".

Literature

- Stafecka, Anna; Mikulėnienė, Danguolė (2009). Atlas of the Baltic languages. Rīga : Vilnius: Latvijas Universitātes Latviešu valodas institūts ; Lietuvių kalbos institutas. ISBN 978-9984-742-49-6.

- Dini, Pietro U. (2000). Baltų kalbos: lyginamoji istorija [Baltic languages: A Comparative History] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 540. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- Palmaitis, Letas [in Lithuanian] (1998). Baltų kalbų gramatinės sistemos raida [Development of the grammatical system of the Baltic Languages: Lithuanian, Latvian, Prussian] (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Kaunas: Šviesa. ISBN 5-430-02651-4.

Further reading

- On Baltic hydronymy

- Fedchenko, Oleg D. (2020). "Baltic Hydronymy of Central Russia". Theoretical and Applied Linguistics (4): 104–127. doi:10.22250/2410-7190_2020_6_4_104_127.

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (National Research University); Gusenkov, Pavel A. (2021). "Revisiting the "West-Baltic" Type Hydronymy in Central Russia". Вопросы Ономастики. 18 (2): 67–87. doi:10.15826/vopr_onom.2021.18.2.019.

- Schmid, Wolfgang P. [in German] (1 January 1973). "Baltische Gewässernamen und das vorgeschichtliche Europa". Indogermanische Forschungen. 77 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1515/if-1972-0102. ISSN 1613-0405.

- Toporov, V. N.; Trubachov, O. N. (1993). "Lіngvіstychny analіz gіdronіmau verkhniaga Padniaprouia" [Linguistic Analysis of Hydronyms of the Upper Dnieper Basin]. Spadchyna (4): 53–62.

- Васильев, Валерий Л. (31 December 2015). "ПРОБЛЕМАТИКА ИЗУЧЕНИЯ ГИДРОНИМИИ БАЛТИЙСКОГО ПРОИСХОЖДЕНИЯ НА ТЕРРИТОРИИ РОССИИ" [The Problems of Studying the Baltic Origins of Hydronyms on the Territory of Russia]. Linguistica. 55 (1): 173–186. doi:10.4312/linguistica.55.1.173-186. ISSN 2350-420X.

- Witczak, Krzysztof Tomasz (2015). "Węgra — dawny hydronim jaćwięski" [Węgra — a Former Yatvingian Hydronym]. Onomastica. 59: 271–279. doi:10.17651/ONOMAST.59.17.

- Yuyukin, Maxim A. (2016). "Из балтийской гидронимии Верхнего Подонья" [From the Baltic hydronymy of the basin of the upper Don]. Žmogus ir žodis. 18 (3): 50–56. doi:10.15823/zz.2016.16.

- On Baltic-Uralic contacts

- Jakob, Anthony (2023). "Baltic → Finnic Loans". A History of East Baltic through Language Contact. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 45–118. doi:10.1163/9789004686472_005. ISBN 978-90-04-68647-2.

- Junttila, Santeri (2012). "The prehistoric context of the oldest contacts between Baltic and Finnic languages". In R. Grünthal; P. Kallio (eds.). A Linguistic map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Vol. 266. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. pp. 261–296. ISBN 978-952-5667-42-4.

- Milanova, Veronika; Metsäranta, Niklas; Honkola, Terhi (2024). "Kinship Terminologies of the Circum-Baltic Area: Convergences and Structural Properties". Journal of Language Contact. 17 (2): 315–358. doi:10.1163/19552629-bja10079.

- Vaba, L (2019). "Welche Sprache sprechen Ortsnamen? Über ostseefinnisch-baltische Kontakte in Abhandlungen über Toponymie von Ojārs Bušs" [The Revealing Language of Place Names: Finnic-Baltic Contacts According to the Toponymic Studies by Ojārs Bušs]. Linguistica Uralica. 55 (1): 47. doi:10.3176/lu.2019.1.05. ISSN 0868-4731.

External links

- Baltic Online by Virginija Vasiliauskiene, Lilita Zalkalns, and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin