The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

| World War II |

|---|

| Navigation |

|

|

| Timelines of World War II |

|---|

| Chronological |

| By topic |

| By theatre |

World War II saw the largest scale of war crimes and crimes against humanity ever committed in an armed conflict, mostly against civilians and specific groups (e.g. Jews, Homosexuals, mentally ill and disabled people) and POWs. Most of these crimes were carried out by the Axis powers who constantly violated the rules of war and the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War, mostly by Nazi Germany[1] and Imperial Japan.[2]

This is a list of war crimes committed during World War II.[3]

Allied powers

Crimes perpetrated by the Soviet Union

| Concurrent with World War II | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Incident | type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

| Katyń massacre | War crimes (murder of Polish intelligentsia) | Lavrenty Beria, Joseph Stalin[4][5][6] | An NKVD-committed massacre of tens of thousands of Polish officers and intelligentsia throughout the spring of 1940. Originally believed to have been committed by the Nazis in 1941 (after the invasion of eastern Poland and the USSR), it was finally admitted by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990 that it had been a Soviet operation. |

| Invasion of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania | War crimes | Vladimir Dekanozov, Andrey Vyshinsky, Andrei Zhdanov, Ivan Serov, Joseph Stalin | An NKVD-committed deportation of hundreds of thousands of Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian intelligentsia, land owners and their families in June 1941 and again in March 1949. |

| NKVD prisoner massacres | War crimes; torture; mass murder | Ivan Serov, Joseph Stalin | An NKVD-committed mass murder. |

| Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war with Iran) | No prosecutions | In contravention of the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact and the 1907 Hague Convention (III), the Soviet Union and Britain jointly invaded neutral Iran without a declaration of war on 25 August 1941 for reasons such as securing the Allied supply lines to the USSR (see the Persian Corridor) and limiting German influence there (the Shah of Iran, Reza Shah, was considered friendly to Nazi Germany). |

| Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush | Crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, genocide | No prosecutions | Deportation of the entire Chechen and Ingush population to Siberia or Centra Asia in 1944. It was acknowledged by the European Parliament as an act of genocide.[7] |

| Deportation of the Crimean Tatars | Crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing | No prosecutions | Forced transfer of the entire Crimean Tatar population to Central Asia or Siberia in 1944. |

| Nemmersdorf massacre, East Prussia | War crimes | No prosecutions | Nemmersdorf (today Mayakovskoye in Kaliningrad Oblast) was one of the first German settlements to fall to the advancing Red Army on 22 October 1944. It was recaptured by the Germans soon afterwards and the German authorities reported that the Red Army killed civilians there. Nazi propaganda widely disseminated the description of the event with horrible details, supposedly to boost the determination of German soldiers to resist the general Soviet advance. Because the incident was investigated by the Nazis and reports were disseminated as Nazi propaganda, discerning the facts from the fiction of the incident is difficult. |

| Invasion of East Prussia Flight and expulsion of Germans from Poland during and after World War II Expulsion of Germans after World War II |

Crimes against humanity (mass expulsion) |

? | War crimes committed against German civilian population by the Red Army in occupied Eastern and Central Germany, and against ethnic-German populations of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Jugoslavia. The number of civilian victims in the years 1944–46 is estimated in at least 300,000, not all victims of war crimes; many died from starvation, cold weather and diseases.[8] |

| Treuenbrietzen | Crimes against humanity (Mass murder of civilians) | ? | Following the capture of the German city of Treuenbrietzen after fierce fighting. Over a period of several days at the end of April and beginning of May roughly 1000 inhabitants of the city, most of them men, were executed by Soviet troops.[12] |

| Rape during the Soviet occupation of Poland (1944–1947) | War crimes (mass rape) | ? | Joanna Ostrowska and Marcin Zaremba of the Polish Academy of Sciences wrote that rapes of the Polish women reached a mass scale during the Red Army's Winter Offensive of 1945.[13] |

| Battle of Berlin | War crimes (Mass rape)[14] | ? | (description/notes missing) |

| Przyszowice massacre | War crimes; crimes against humanity | No prosecution | A massacre perpetrated by the Red Army against civilian inhabitants of the Polish village of Przyszowice in Upper Silesia during the period 26 to 28 January 1945. Sources vary on the number of victims, which range from 54[15] to over 60 – and possibly as many as 69.[16] |

| Gegenmiao massacre | War crimes; crimes against humanity | No prosecution | A massacre perpetrated by the Red Army against Japanese refugees in Inner Mongolia during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria.[17] The Red Army murdered over 1,000 Japanese refugees by the end of the massacre.[18] |

Crimes perpetrated by the United Kingdom

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant shipping | Breach of London Naval Treaty (1930) | No prosecutions; Allied representatives admitted responsibility at Nuremberg Trials; questionable whether war crime or a breach of a treaty. | It was the conclusion of the Nuremberg Trials of Karl Dönitz that Britain had been in breach of the Treaty "in particular of an order of the British Admiralty announced on 8 May 1940, according to which all vessels should be sunk at sight in the Skagerrak."[19] |

| Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against Iran) | No prosecutions | In contravention of the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact and the 1907 Hague Convention (III), Britain and the Soviet Union jointly invaded neutral Iran without a declaration of war on 25 August 1941 for reasons such as securing the Allied supply lines to the USSR (see the Persian Corridor) and limiting German influence there (the Shah of Iran, Reza Shah, was considered friendly to Nazi Germany). |

| HMS Torbay incident | War crimes (murder of shipwreck survivors) | No prosecutions | In July 1941, the submarine HMS Torbay (under the command of Anthony Miers) was based in the Mediterranean where it sank several German ships. On two occasions, once off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt, and the other off the coast of Crete, the crew attacked and killed dozens of shipwrecked German sailors and troops. None of the shipwrecked survivors posed a major threat to Torbay's crew. Miers made no attempt to hide his actions, and reported them in his official logs. He received a strongly worded reprimand from his superiors following the first incident. Miers' actions violated the Hague Convention of 1907, which banned the killing of shipwreck survivors under any circumstances.[20][21] |

| Sinking of German hospital ship Tubingen | War crimes (attacking hospital ships) | No prosecutions | On 18 November 1944, the German hospital ship Tubingen was sunk by two British Beaufighter bombers off Pola, in the Adriatic Sea. The vessel, which had paid a brief visit to the Allied-controlled port of Bari to pick up German wounded under the auspices of the Red Cross, was attacked with rockets nine times, despite the calm sea and good weather allowed a clear identification of the ship's Red Cross markings. Six crewmembers were killed.[22] American author Alfred M. de Zayas, who evaluated the 266 extant volumes of the Wehrmacht War Crimes Bureau, identifies the sinking of Tübingen and other German hospital ships as war crimes according to the Hague Convention (X) of 1907.[23] |

Crimes perpetrated by the United States

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant shipping | Breach of London Naval Treaty (1930) | No prosecutions; Chester Nimitz admitted responsibility at Nuremberg Trials; questionable whether war crime or a breach of a treaty. | During the post war Nuremberg Trials, in evidence presented at the trial of Karl Dönitz on his orders to the U-boat fleet to breach the London Rules, Admiral Chester Nimitz stated that unrestricted submarine warfare was carried on in the Pacific Ocean by the United States from the first day that nation entered the war.[19] |

| Canicattì massacre | War crimes (murder of civilians) | Lieutenant Colonel George H. McCaffrey was never prosecuted and died in 1954 | During the Allied invasion of Sicily, eight civilians were killed by Lieutenant Colonel George H. McCaffrey, though the exact number of casualties is uncertain.[24] |

| Biscari Massacre | War crimes (murder of POWs) | Sergeant Horace T. West: court-martialed for murder, found guilty, stripped of rank and sentenced to life in prison, albeit he was released as a private one year later. Captain John T. Compton was court-martialed for killing 40 POWs in his charge. He claimed to be following orders. The investigating officer and the Judge Advocate declared that Compton's actions were unlawful, but he was acquitted. Compton was killed in action in November 1943. | Following the capture of Biscari Airfield in Sicily on 14 July 1943, seventy-six German and Italian POWs were shot by American troops of the 180th Regimental Combat Team, 45th Division during the Allied invasion of Sicily. These killings occurred in two separate incidents between July and August 1943. |

| Dachau liberation reprisals | War crimes (murder of POWs) | Investigated by U.S. forces, found lack of evidence to charge any individual, and a lack of evidence of any practice or policy; however, did find that SS guards were separated from Wehrmacht (regular German Army) prisoners before their deaths. | Some Death's Head SS guards of the Dachau concentration camp allegedly attempted to escape, and were shot. |

| Salina, Utah POW massacre | War crimes (murder of POWs) | Private Clarence V. Bertucci determined to be insane and confined to a mental institution | Private Clarence V. Bertucci fired a machine gun from one of the guard towers into the tents that were being used to accommodate the German prisoners of war. Nine were killed and 20 were wounded. |

| American mutilation of Japanese war dead[25][26][27] | War crimes (abuse of remains) | Though there are no known prosecutions, the occasional mutilation of Japanese remains were recognised to have been conducted by U.S. forces, declared to be atrocities, and explicitly forbidden by order of the U.S. Judge Advocate General in 1943–1944. | Many dead Japanese were desecrated and/or mutilated, for example by taking body parts (such as skulls) as souvenirs or trophies. This is in violation of the law and custom of war, as well as the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Sick and Wounded which was paraphrased as saying "After every engagement, the belligerent who remains in possession of the field shall take measures to search for wounded and the dead and to protect them from robbery and ill-treatment." in a 1944 memorandum for the U.S. Assistant Chief of the Staff.[28][29] |

Crimes perpetrated by Canada

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Razing of Friesoythe | Breach of The 1907 Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV), Article 23, which prohibits acts that "destroy or seize the enemy's property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war."[30] | No investigation; No prosecutions. Major-general Christopher Vokes commander of the Canadian 4th Armoured Division freely admitted ordering the action, commenting in his autobiography that he had "No feeling of remorse over the elimination of Friesoythe."[31][32] | In April 1945 the town of Friesoythe in north-west Germany was deliberately destroyed by the Canadian 4th Armoured Division acting on the orders of its commander, Major-general Christopher Vokes. The destruction was ordered in retaliation for the killing of a Canadian battalion commander. Vokes may have believed at the time that this killing had been carried out by German civilians. The rubble of the town was used to fill craters in the local roads. |

Crimes perpetrated by the Yugoslav Partisans

| Armed conflict | Perpetrator | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| World War II in Yugoslavia | Yugoslav Partisans | ||

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

| Bleiburg repatriations | War crimes, crimes against humanity, death marches | No prosecutions. | The victims were Yugoslav collaborationist troops (ethnic Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes), executed without trial as an act of vengeance for the genocide committed by the pro-Axis collaborationist regimes (in particular the Ustaše) installed by the Nazis during the World War II occupation of Yugoslavia. Civilians were also killed. Estimates vary significantly, questioned by a number of historians. |

| Foibe massacres | War crimes, crimes against humanity, murder of prisoners of war and civilians, ethnic cleansing | No prosecutions.[33] | Following Italy's 1943 armistice with the Allied powers up to 1947, OZNA and Yugoslav Partisans executed in Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner and Dalmatia a number between 11,000[34][35] and 20,000[36] of the local ethnic Italian population (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), as well against anti-communists in general (even Croats and Slovenes), usually associated with Fascism, Nazism and collaboration with Axis,[36][34] as well as against real, potential or presumed opponents of Tito communism.[37] The type of attack was state terrorism,[36][38] reprisal killings,[36][39] and ethnic cleansing against Italians.[36][40][41][42][43] The foibe massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.[44] |

| Communist purges in Serbia in 1944–1945 | War crimes, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing | No prosecutions. | 1944–1945 killings of ethnic Hungarians in Bačka. |

| Persecution of Danube Swabians | War crimes, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing | In a unanimously approved motion in 1950, the Federal Council called on the Federal Government to commit itself, based on the prisoner of war agreement, to the return of German prisoners of war condemned in the Soviet Union and in Yugoslavia. Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer described in January 1950 the convictions of German prisoners of war in Yugoslavia as "crimes and crimes against humanity".[45] |

In Yugoslavia in particular, with many exceptions, the Danube Swabian minority "collaborated . . . with the occupation".[46] Consequently, on 21 November 1944 the Presidium of the AVNOJ (the Yugoslav parliament) declared the ethnic German minority in Yugoslavia collectively hostile to the Yugoslav state. The AVNOJ Presidium issued a decree that ordered the government confiscation of all property of Nazi Germany and its citizens in Yugoslavia, persons of ethnic German nationality (regardless of citizenship), and collaborators. The decision acquired the force of law on 6 February 1945.[47] Of a pre-war population of about 350,000 ethnic Germans in the Vojvodina, the 1958 census revealed 32,000 left. Officially, Yugoslavia denied the forcible starvation and killing of their Schwowisch populations, but reconstruction of the labor camps reveals that of the 170,000 Danube Swabians interned from 1944 to 1948, over 50,000 died of mistreatment.[48] About 55,000 people died in the concentration camps, another 31,000 died serving in the German armed forces, and about 31,000 disappeared, mostly likely dead, with another 37,000 still unaccounted for. Thus the total victims of the war and subsequent ethnic cleansing and killings comprised about 30% of the pre-war German population.[49] In addition, 35,000–40,000 Swabian children under age sixteen were separated from their parents and force into prison camps and re-education orphanages. Many were adopted by Serbian Partisan families.[50] |

Axis powers

The Axis powers (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan) were some of the most systematic perpetrators of war crimes in modern history. The factors which contributed to Axis war crimes included Nazi racial theories, the desire for "living space" which was used as a justification for the eradication of native populations, and militaristic indoctrination that encouraged the terrorization of conquered peoples and prisoners of war. The Holocaust, the German attack on the Soviet Union and the German occupation of much of Europe, the Japanese invasion and occupation of Manchuria, the Japanese invasion of China and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines all contributed to well over half of all of the civilian deaths in World War II as well as the conflicts that led up to the war. Even before post-war revelations of atrocities, Axis military forces were notorious for their brutal treatment of captured combatants.

Crimes perpetrated by Germany

According to the Nuremberg Trials, there were four major categories of crimes alleged against the German political leadership, the ruling party NSDAP, the military high command, the paramilitary SS, the security services, the civil occupation authorities, as well as individual government officials (including members of the civil service or the diplomatic corps), soldiers or members of paramilitary formations, industrialists, bankers and media proprietors, each with individual events that made up the major charges. The crime of genocide was later raised to a separate, fifth category.

- Participation in a common plan of conspiracy for the accomplishment of crimes against peace

- Planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression and other crimes against peace

- Planning and executing a campaign of invasion of its European neighbours, as well as the conspiracy to violate the Treaty of Versailles and the Treaty of Saint-Germain through the remilitarisation of the Rhineland, and the annexations of Austria and Czechoslovakia.

- War crimes – atrocities against enemy combatants or conventional crimes committed by military units (see War crimes of the Wehrmacht), and include:

- Invasion of Poland without a formal declaration of war: During the period of 1 September – 25 October 1939 German forces in their military actions engaged in executions of Polish POWs, bombing hospitals, murdering civilians, shooting refugees, and executing wounded soldiers. The cautious estimates give a number of at least 16,000 murdered victims.[51]

- Wawer massacre: the execution of 107 Polish civilians on the night of 26 to 27 December 1939 by the Nazi German occupiers of Wawer (near Warsaw), Poland. The execution was a response to the deaths of two German NCOs. 120 people were arrested and 114 were shot, of whom 7 survived.

- Pacification Operations in German occupied Poland: During the occupation of Poland by German Reich, Wehrmacht forces took part in several pacification actions in rural areas, that resulted in murder of at least 20,000 Polish villagers.

- Le Paradis massacre: In May 1940, British soldiers of the Royal Norfolk Regiment were captured by the SS and subsequently murdered. Fritz Knoechlein was tried, found guilty, and hanged for ordering the massacre.

- Wormhoudt massacre: In May 1940, British and French soldiers were captured by the SS and subsequently murdered. No one found guilty of the crime.

- Normandy Massacres, a series of killings in which up to 156 Canadian prisoners of war were murdered by soldiers of the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitler Youth) during the Battle of Normandy

- Ardenne Abbey massacre, one of the Normandy massacres; June 1944 Canadian soldiers captured by the SS and murdered by 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. SS General Kurt Meyer (Panzermeyer) sentenced to be shot 1946; sentence commuted; released 1954[52]

- Malmedy massacre: In December 1944, United States POWs captured by Kampfgruppe Peiper were murdered outside Malmedy, Belgium

- Wereth 11 Massacre was the massacre of 11 Black soldiers from the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion (United States). by the SS during the Battle of the Bulge

- Graignes massacre: 11 June 1944, United States POWs that had surrendered to 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen were bayonetted and shot

- Gardelegen (war crime): The German SS coerced 1,016 forced labourers who were part of transports evacuated from several sub-camps of Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp and from the sub-camp Hannover-Stöcken of Neuengamme Concentration Camp into a large barn which was then lit on fire. Most of the prisoners were burned alive; some were shot trying to escape.

- Marzabotto massacre: The German SS killing of at least 770 civilians of Marzabotto as a collective punishment for their support of Italian partisans and the Italian resistance movement

- Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre: A massacre was committed in the hill village of Sant'Anna di Stazzema in Tuscany, Italy, in the course of an operation against the Italian resistance movement during the Italian Campaign of World War II. 560 local villagers and refugees were murdered and their bodies burnt in a scorched earth policy action by the Nazis.

- Cefalonia Massacre: The mass execution of the men of the Italian 33rd Acqui Infantry Division by the Germans on the island of Cephalonia, Greece was committed after the Italian armistice.

- Oradour-sur-Glane massacre: On 10 June 1944, the village of Oradour-sur-Glane in Haute-Vienne in then Nazi occupied France was destroyed. 642 of its inhabitants, including women and children, were massacred by a Waffen-SS company.

- Massacre of Kalavryta: The extermination of the male population and the total destruction of the town of Kalavryta, in Greece, by German occupying forces during World War II, was committed on 13 December 1943.

- Distomo massacre: This attack was perpetrated by members of the Waffen-SS in the village of Distomo, Greece, during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II.

- Kragujevac massacre: This was a Nazi war crime and partially an act of genocide in which Serbs, Jews and Roma men and boys in Kragujevac, Serbia, were murdered by German Wehrmacht soldiers on 20 and 21 October 1941.

- The crimes during the 1944 Warsaw uprising such as the Wola massacre or the Ochota massacre

Polish civilians murdered during the Wola massacre in Warsaw, August 1944 - The planned destruction of Warsaw (levelling of the whole city) following the fall of the Warsaw Uprising

German Brandkommando (Burning Detachment) destroying Warsaw.[53] Taken on Leszno street. From left: building No. 24, 22 & part of 20.[54] - The annihilation of the Czech village of Lidice was committed as an act of vengeance for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

- The treatment of Soviet POWs throughout the war, who were not given the protections and guarantees of the Geneva Convention unlike other Allied prisoners was a war crime. Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs, resulted in some 3.3 million to 3.5 million deaths. This accounts for about 60% of all Soviet POWs.[55]

Naked Soviet prisoners of war in Mauthausen concentration camp. Unknown date - The Arnsberg Forest massacre, in which 3 mass killings of 208 forced labourers and Prisoners of war, mostly Russian and Polish, took place in March 1945.

- Unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant shipping was another war crime.

- Nazi looting of Poland

- Commando Order which stated that Allied combatants encountered during commando operations were to be executed immediately upon capture and without trial, even if they were properly uniformed, unarmed, or intending to surrender was a war crime.

- Commissar Order: An order stating that Soviet political commissars found among captured troops were to be executed immediately was a war crime.

- Nacht und Nebel directive, targeting political activists and resistance "helpers" in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany during the World War II, who were to be imprisoned, murdered, or made to disappear, while the family and the population remained uncertain as to the fate or whereabouts of alleged offender against the Nazi German occupation power

- Vinkt massacre: In May 1940 at least 86 civilians in Vinkt were killed by the German Wehrmacht.

- Heusden: A town hall was massacred in November 1944.

- German war crimes during the Battle of Moscow are another example.

- Crimes against humanity – crimes committed well away from the lines of battle and unconnected directly to ongoing military activity, distinct from war crimes

- The employment of concentration camps across Europe, including Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Mauthausen, Bergen-Belsen, Natzweiler-Struthof, Esterwegen, Stutthof, Potulice and Auschwitz I which held POWs and political prisoners in inhuman conditions, and transported Jews and Roma to extermination camps

- The Generalplan Ost, including the Pabst Plan:

- Łapankas or "Catching Roundups", – Nazi roundups of Poles, usually completely random, in the major cities for forced labour or for keeping as hostages, summarily executed in highly publicized terror reprisals with an intended punintive and deterring effect, following each of attempted or completed ambush attacks against German forces as well as assassinations of German occupation officials or their prominent local collaborators

Announcement of execution of 150 Polish hostages as revenge for assassination of 6 Germans, Warsaw, Nazi-occupied Poland, May 1944 - The Operation Tannenberg based on the Special Prosecution Book-Poland, the AB Action, the Intelligenzaktion (including Intelligenzaktion Pommern and Sonderaktion Krakau), resulting in numerous summary murders such as the Bydgoszcz Valley of Death, the massacres in Piaśnica, the Forest of Szpęgawsk massacre, the Rudzki Most massacre, the Palmiry massacre, and the massacres following the German invasion of the Soviet Union: the massacre of Lwów professors, the Ponary massacre and the Czarny Las massacre; any Nazi actions in Poland meant to mass murder the Polish intelligentsia and other potential leaders of resistance.[56][57]

Polish teachers from Bydgoszcz guarded by members of Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz before execution - Expulsion of Poles by Nazi Germany, including expulsions from the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, the Action Saybusch, the ethnic cleansing of Zamojszczyzna, and the planned settlement of Wehrbauers.

- Nur für Deutsche apartheid policy in occupied Poland and the so-called Polish decrees concerning the Polish labourers in Germany

- The widespread use of forced/unfree labour by the Nazi regime, including forced labor in Nazi concentration camps

- Nazi destruction of Polish culture and suppression of Polish higher education institutions

- The Hunger Plan

- Łapankas or "Catching Roundups", – Nazi roundups of Poles, usually completely random, in the major cities for forced labour or for keeping as hostages, summarily executed in highly publicized terror reprisals with an intended punintive and deterring effect, following each of attempted or completed ambush attacks against German forces as well as assassinations of German occupation officials or their prominent local collaborators

- Aktion T4, the Nazi "euthanasia" program, under which an estimated 200,000 mentally or physically handicapped people were murdered.

- The persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany, including their extermination

- The crime of genocide, initially classified as a type of crimes against humanity, later defined as a distinct type of crime

- The Final Solution, including the Holocaust, the genocide of the European Jews, as well as the Porajmos, the genocide of the Romany peoples of Europe by the Nazis including:

- The construction and use of Vernichtungslagern (extermination camps) to commit genocide, most prominently at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Majdanek, Bełżec, Sobibór, and Chełmno

- Death marches of prisoners, particularly in the last months of the war when the aforementioned camps were being overrun by the Allies

- the use of extermination camp prisoners as forced labourers, with the intent of extermination through labour

- The establishment of Jewish Ghettos in Eastern Europe intended to isolate Jewish communities for deportation and subsequent extermination

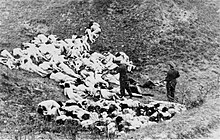

German police shooting women and children from the Mizocz Ghetto, 14 October 1942 - The use of SS Einsatzgruppen, mobile extermination squads, to exterminate Jews and anti-nazi "partisans"

- Babi Yar a series of massacres in Kiev, the most notorious and the best documented of these massacres took place on 29–30 September 1941, wherein 33,771 Jews were killed in a single operation. The decision to kill all the Jews in Kiev was made by the military governor, Major-General Kurt Eberhard, the Police Commander for Army Group South, SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, and the Einsatzgruppe C Commander Otto Rasch. It was carried out by Sonderkommando 4a soldiers, along with the aid of the SD and SS Police Battalions backed by the local police.

- Rumbula a collective term for incidents on two non-consecutive days (30 November and 8 December 1941) in which about 25,000 Jews were killed in or on the way to Rumbula forest near Riga, Latvia, during the Holocaust

- Ninth Fort By the order of SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger and SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca, the Sonderkommando under the leadership of SS-Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann, and 8 to 10 men from Einsatzkommando 3, in collaboration with Lithuanian partisans, murdered 2,007 Jewish men, 2,920 women, and 4,273 children in a single day at the Ninth Fort, Kaunas, Lithuania.

- Simferopol Germans perpetrated one of the largest war-time massacres in Simferopol, killing in total over 22,000 locals—mostly Jews, Russians, Krymchaks, and Gypsies.[58] On one occasion, starting 9 December 1941, the Einsatzgruppen D under Otto Ohlendorf's command killed an estimated 14,300 Simferopol residents, most of them being Jews.[59]

- The massacre of 100,000 Jews and Poles at Paneriai

Aleksandras Lileikis, a Nazi Saugumas unit commander who oversaw the murder of 60,000 Jews in Lithuania. He later worked for the CIA.[60] - Nikolaev massacre, which resulted in the deaths of 35,782 Soviet citizens, most of whom were Jews.

- The suppression of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising which erupted when the SS came to clear the Jewish ghetto and send all of the occupants to extermination camps

- Izieu Massacre Izieu was the site of a Jewish orphanage during the Second World War. On 6 April 1944, three vehicles pulled up in front of the orphanage. The Gestapo, under the direction of the 'Butcher of Lyon' Klaus Barbie, entered the orphanage and forcibly removed the forty-four children and their seven supervisors, throwing the crying and terrified children on to the trucks. Following the raid on their home in Izieu, the children were shipped directly to the "collection center" in Drancy, then put on the first available train towards the concentration camps in the East.

- The construction and use of Vernichtungslagern (extermination camps) to commit genocide, most prominently at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, Majdanek, Bełżec, Sobibór, and Chełmno

- The genocidal kidnapping of children by Nazi Germany for programmes such as Lebensborn

Kidnapping of Polish children during the "resettlement" operation in Zamość county

- The Final Solution, including the Holocaust, the genocide of the European Jews, as well as the Porajmos, the genocide of the Romany peoples of Europe by the Nazis including:

At least 10 million, and perhaps over 20 million perished directly and indirectly due to the commission of crimes against humanity and war crimes by Hitler's regime, of which the Holocaust lives on in particular infamy, for its particularly cruel nature and scope, and the industrialised nature of the genocide of Jewish citizens of states invaded or controlled by the Nazi regime. At least 5.9 million Jews were murdered by the Nazis, or 66 to 78% of Europe's Jewish population, although a complete count may never be known. Though much of Continental Europe suffered under the Nazi occupation, Poland, in particular, was the state most devastated by these crimes, with 90% of its Jews as well as many ethnic Poles slaughtered by the Nazis and their affiliates. After the war, from 1945 to 1949, the Nazi regime was put on trial in two tribunals in Nuremberg, Germany by the victorious Allied powers.

The first tribunal indicted 24 major Nazi war criminals, and resulted in 19 convictions (of which 12 led to death sentences) and 3 acquittals, 2 of the accused died before a verdict was rendered, at least one of which by killing himself with cyanide.[61] The second tribunal indicted 185 members of the military, economic, and political leadership of Nazi Germany, of which 142 were convicted and 35 were acquitted. In subsequent decades, approximately 20 additional war criminals who escaped capture in the immediate aftermath of World War II were tried in West Germany and Israel. In Germany and many other European nations, the Nazi Party and denial of the Holocaust is outlawed.[citation needed]

Crimes perpetrated by Hungary

| Incident | Type of crime | People responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novi Sad massacre[62][63] | Crimes against humanity | After the war, most of the perpetrators were convicted by the People's Tribunal. The leaders of the massacre, Ferenc Feketehalmy-Czeydner, József Grassy and Márton Zöldy were sentenced to death and later extradited to Yugoslavia, together with Ferenc Szombathelyi, Lajos Gaál, Miklós Nagy, Ferenc Bajor, Ernő Bajsay-Bauer and Pál Perepatics. After a trial at Novi Sad, all sentenced to death and executed. | 4,211 civilians (2,842 Serbs, 1,250 Jews, 64 Roma, 31 Rusyns, 13 Russians and 11 ethnic Hungarians) rounded up and killed by Hungarian troops in reprisal for resistance activities. |

| Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre[64][65] | Crimes against humanity; crime of genocide | After the war, the perpetrator of the massacre, Friedrich Jeckeln was sentenced to death and executed in the Soviet Union. | 14000-16000 Jews were deported by Hungarian troops to Kamianets-Podilskyi to be executed by SS troops. Part of the first large-scale mass murder in pursuit of the "Final Solution". |

| Sarmasu massacre[66][67] | Crimes against humanity | The People's Tribunal at Cluj sentenced to death 7 Hungarian officer in absentia, two local Hungarian were sentenced to imprisonment. | Torture and killing of 126 Jews by Hungarian troops in the village of Sarmasu. |

| Treznea massacre[68] | Crimes against humanity | The People's Tribunal at Cluj sentenced to death Ferenc Bay in absentia, 3 local Hungarian were sentenced to imprisonment, 2 person were acquitted. | 93 to 236 Romanian and Jewish civilians (depending on sources) executed as reprisal for alleged attacks from locals on the Hungarian troops. |

| Ip massacre[68] | Crimes against humanity | A Hungarian officer was sentenced to death by the People's Tribunal at Cluj in absentia, 13 local Hungarians were sentenced to imprisonment, 2 person were acquitted. | 150 Romanian civilians executed by Hungarian rogue troops and paramilitary formations as reprisal for the death of two Hungarian soldiers in an explosion. |

| Hegyeshalom death march[69][70] | Crimes against humanity; crime of genocide | After the war most of the responsibles were sentenced by the Hungarian people's tribunals, including the whole Szálasi-government | About 10,000 Budapest Jews died as a result of exhaustion and executions while marching toward Hegyeshalom at the Austrian border. |

Crimes perpetrated by Italy

- Invasion of Abyssinia: Waging a war of aggression for territorial aggrandisement, war crimes, use of poisons as weapons, crimes against humanity; in violation of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, and the customary law of nations, Italy invaded the Kingdom of Abyssinia in 1936 without cause cognisable by the law of nations, and waged a war of annihilation against Ethiopian resistance, using poisons against military forces and civilian persons alike, not giving quarter to POWs who had surrendered, and massacring civilians, including the killing of 19,000-30,000 civilians in the 1937 Yekatit 12 massacre.

- Invasion of Albania: Waging a war of aggression for territorial aggrandisement; Italy invaded the Kingdom of Albania in 1939 without cause cognisable by the law of nations in a brief but bloody affair that saw King Zog deposed and an Italian proconsul installed in his place. Italy subsequently acted as the suzerain of Albania until its ultimate liberation later in World War II.

- Invasion of Yugoslavia: Aerial bombardment of civilian population; internment of tens of thousands of civilians in concentration camps (Rab: 3,500 – 4,641 killed, Gonars: over 500 killed, Molat: 1,000 killed).

- "Circular 3C" policy, implemented by Mario Roatta,[71] which included the tactics of "summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages."[72]

- Massacres of civilians, such as in Podhum.

- Italian invasion and occupation of Greece: Domenikon massacre.

- No one has been brought to trial for war crimes, although in 1950 the former Italian defence minister was convicted for collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Crimes perpetrated by the (first) Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

- deportation of around 70,000 Slovak Jews into German Nazi concentration camps

- annihilation of 60 villages and their inhabitants[73]

- deportation of Slovak Jews, Roma and political opponents into Slovak forced labour camps in Sereď, and Nováky

- brought to trial and sentenced to death: Jozef Tiso, Ferdinand Ďurčanský (he fled), Vojtech Tuka and 14 others[74]

Crimes perpetrated by Japan

This section includes war crimes which were committed from 7 December 1941 when the United States was attacked by Imperial Japan and entered World War II. For war crimes which were committed before this date, specifically for war crimes which were committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War, please see the section above which is titled 1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War.

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| World War II [citation needed] | Crimes against peace (overall waging and/or conspiracy to wage a war of aggression for territorial aggrandisement, as established by the Tokyo Trials) | General Kenji Doihara, Baron Kōki Hirota, General Seishirō Itagaki, General Heitarō Kimuna, General Iwane Matsui, General Akira Mutō, General Hideki Tōjō, General Sadao Araki, Colonel Kingoro Hashimoto, Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, Baron Hiranuma Kiichirō, Naoki Hoshino, Okinori Kaya, Marquis Kōichi Kido, General Kuniaki Koiso, General Jiro Minami, Admiral Takasumi Oka, General Hiroshi Ōshima, General Kenryo Sato, Admiral Shigetaro Shimada, Toshio Shiratori, General Teiichi Suzuki, General Yoshijirō Umezu, Shigenori Tōgō, Mamoru Shigemitsu | The persons responsible were tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. |

| Attack on the United States in 1941[75] | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against the United States) (count 29 at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Kenji Doihara, Shunroku Hata, Hiranuma Kiichirō, Naoki Hoshino, Seishirō Itagaki, Okinori Kaya, Kōichi Kido, Heitarō Kimura, Kuniaki Koiso, Akira Mutō, Takasumi Oka, Kenryo Sato, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Shigetarō Shimada, Teiichi Suzuki, Shigenori Tōgō, Hideki Tōjō, Yoshijirō Umezu[75] | Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet was ordered by his militarist superiors to start the war with a bloody sneak attack on a U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 7 December 1941. The attack was in violation of the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, which prohibited war of aggression, and the 1907 Hague Convention (III), which prohibited the initiation of hostilities without explicit warning, since the U.S. was officially neutral and was attacked without a declaration of war or an ultimatum at that time.[76] In addition, Japan violated the Four-Power Treaty by attacking and invading the U.S. territories of Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines which began simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor.[citation needed] |

| Attack on the British Commonwealth in 1941[75] | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against the British Commonwealth (count 31 at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Kenji Doihara, Shunroku Hata, Hiranuma Kiichirō, Naoki Hoshino, Seishirō Itagaki, Okinori Kaya, Kōichi Kido, Heitarō Kimura, Kuniaki Koiso, Akira Mutō, Takasumi Oka, Kenryo Sato, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Shigetarō Shimada, Teiichi Suzuki, Shigenori Tōgō, Hideki Tōjō, Yoshijirō Umezu[75] | Simultaneously with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 (Honolulu time), Japan invaded the British colonies of Malaya and bombed Singapore and Hong Kong, without a declaration of war or an ultimatum, which was in violation of the 1907 Hague Convention (III) and the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact since Britain was officially neutral with Japan at the time.[77][78] |

| Attack On Dutch Colonial Possessions In 1941 | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against the Netherlands (count 32 at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Kenji Doihara, Shunroku Hata, Hiranuma Kiichirō, Naoki Hoshino, Seishirō Itagaki, Okinori Kaya, Kōichi Kido, Heitarō Kimura, Kuniaki Koiso, Akira Mutō, Takasumi Oka, Kenryo Sato, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Shigetarō Shimada, Teiichi Suzuki, Shigenori Tōgō, Hideki Tōjō, Yoshijirō Umezu[75] | In addition to the attacks against the United States, the British Commonwealth and French Colonial Possessions in the far east, the Japanese military and navy invaded the Dutch East Indies (Now Indonesia and New Guinea) which was a violation of the 1907 Hague Convention (III) |

| Attack On French Colonial Possessions in 1940-41 | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against France in Indochina (count 33 at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Mamoru Shigemitsu, Hideki Tōjō[75] | When France surrendered to Germany in 1940, Japan asked for permission from the French State to be allowed to make airbases in northern French Indochina. Even though the French State consented to this. In 1941 Japan occupied the entire French colony in violation of existing agreements with the French State, the French Government in Exile never recognized the occupation. |

| Aggression Against the Soviet Union | Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war against the USSR (counts 35 and 36 or both at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Kenji Doihara, Hiranuma Kiichirō, Seishirō Itagaki[75] | This was for Japanese Aggression including the battle for Khalkin Gol and many other border skirmishes against the USSR during the war. This while ambiguous, was included in the Tokyo Trial at behest of the USSR |

| Nanjing Massacre; Narcotics Trafficking; Bacteriological Warfare[75] | War crimes ("ordered, authorised, and permitted" torture and inhumane treatment of Prisoners of War (POWs) and others (count 54 at the Tokyo Trials)[75] | Kenji Doihara, Seishirō Itagaki, Heitarō Kimura, Akira Mutō, Hideki Tōjō[75] | (Description/notes missing) |

| "Black Christmas", Hong Kong, 25 December 1941,[79] | Crimes against humanity (murder of civilians; mass rape, torture, looting) | No specific prosecutions, although the conviction and execution of Takashi Sakai included some activities in Hong Kong during the time frame | On the day of the British surrender of Hong Kong to the Japanese, the Japanese committed atrocities against the local Chinese, most notably thousands of cases of rape. During the three-and-a-half-year Japanese occupation, an estimated 10,000 Hong Kong civilians were executed, while many others were tortured, raped, or mutilated.[80] |

| Banka Island massacre, Dutch East Indies, 1942 | Crimes against humanity (murder of civilians) | No prosecutions | The merchant ship Vyner Brooke was sunk by Japanese aircraft. The survivors who made it to Banka Island were all shot or bayonetted, including 22 nurses ordered into the sea and machine-gunned. Only one person survived the massacre, nurse Vivian Bullwinkel, who later testified at a war crimes trial in Tokyo in 1947.[81] |

| Bataan Death March, Philippines, 1942 | Crime of torture, war crimes (Torture and murder of POWs) | General Masaharu Homma was convicted by an Allied commission of war crimes for failing to prevent atrocities from occurring, including the atrocities of the death march out of Bataan, and the atrocities at Camp O'Donnell and Cabanatuan that followed. He was sentenced to death and executed on 3 April 1946 outside Manila.

Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano were found guilty of ordering the march and sentenced to death. They were both sentenced to death and hanged on 12 June 1949 in Sugamo Prison . |

Approximately 75,000 Filipino and US soldiers, commanded by Major General Edward P. King Jr. formally surrendered to the Japanese, under General Masaharu Homma, on 9 April 1942. Captives were forced to march, beginning the next day, about 100 kilometers north to Nueva Ecija to Camp O'Donnell, a prison camp. Prisoners of war were beaten randomly and denied food and water for several days. Those who fell behind were executed through various means: shot, beheaded or bayoneted. Deaths estimated at 650–1,500 U.S. and 2,000 to over 5,000 Filipinos,[82][83] |

| Enemy Airmen's Act | War crimes (murder of POWs) | General Shunroku Hata | Promulgated on 13 August 1942 to try and execute captured Allied airmen taking part in bombing operations against targets in Japanese-held territory. The Act contributed to the murder of hundreds of Allied airmen throughout the Pacific War.[citation needed] |

| Operation Sankō (Three Alls Policy) | Crimes against humanity (murder of civilians) | General Yasuji Okamura | Authorised in December 1941 to implement a scorched earth policy in North China by Imperial General Headquarters. According to historian Mitsuyoshi Himeta, "more than 2.7 million" civilians were killed in this operation that began in May 1942.[84] |

| Parit Sulong massacre, Malaysia, 1942 | War crimes (murder of POWs) | Lieutenant General Takuma Nishimura, was convicted for this crime by an Australian Military Court and hanged on 11 June 1951.[85] | Recently captured Australian and Indian POWs, who had been too badly wounded to escape through the jungle, were murdered by Japanese soldiers. Accounts differ on how they were killed. Two wounded Australians managed to escape the massacre and provide eyewitness accounts of the Japanese treatment of wounded prisoners of war, as did locals who witnessed the massacre. Official records indicate that 150 wounded men were killed. |

| Laha massacre, 1942 | War crimes (murder of POWs) | In 1946, the Laha massacre and other incidents which followed the fall of Ambon became the subject of the largest ever war crimes trial, when 93 Japanese personnel were tried by an Australian tribunal, at Ambon. Among other convictions, four men were executed as a result. Commander Kunito Hatakeyama, who was in direct command of the four massacres, was hanged; Rear Admiral Koichiro Hatakeyama, who was found to have ordered the killings, died before he could be tried.[86] | After the battle Battle of Ambon, more than 300 Australian and Dutch prisoners of war were chosen at random and summarily executed, at or near Laha airfield in four separate massacres. "The Laha massacre was the largest of the atrocities committed against captured Allied troops in 1942".[87] |

| Palawan massacre, 1944 | War crimes (murder of POWs) | In 1948, in Lt. Gen. Seiichi Terada was accused of failing to take command of the soldiers in the Puerto Princesa camp. Master Sgt. Toru Ogawa and Superior Private Tomisaburo Sawa were the only few soldiers who were charged for the actual involvement since most of the soldiers garrisoned in the camp had either died or went missing in the days following the victory of the Philippines campaign. In 1958, all charges were dropped and sentences were reduced. | Following the US invasion of Luzon in 1944, the Japanese high command ordered that all POWs remaining in the island are to be exterminated at all cost. As a result, on 14 December 1944, units from the Japanese Fourteenth Area Army stationed in the Puerto Princesa POW camp in Palawan rounded up 150 remaining POWs still garrisoned in the camp, herded them into air raid shelters, before dousing the shelters with gasoline and setting it on fire. Of the handful of POWs that were able to escape the flames were hunted before being gunned down, bayonetted, or burned alive. Only 11 POWs survived the ordeal and were able to escape to Allied lines to report the incident.[88] |

| Alexandra Hospital massacre, Battle of Singapore, 1942 | Crimes against humanity (murder of civilians) | No prosecutions | At about 1 pm on 14 February, Japanese approached Alexandra Barracks Hospital. Although no resistance was offered, some staff members and patients were shot or bayoneted. The remaining staff and patients were murdered over the next two days, 200 in all.[89] |

| Sook Ching massacre, 1942 | Crimes against humanity (mass murder of civilians) | In 1947, the British Colonial authorities in Singapore held a war crimes trial to bring the perpetrators to justice. Seven officers, were charged with carrying out the massacre. While Lieutenant General Saburo Kawamura, Lieutenant Colonel Masayuki Oishi received the death penalty, the other five received life sentences. | The massacre (estimated at 25,000–50,000)[90][91] was a systematic extermination of perceived hostile elements among the Chinese in Singapore by the Japanese military administration during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore, after the British colony surrendered in the Battle of Singapore on 15 February 1942.[citation needed] |

| Changjiao massacre, China, 1943 | Crimes against humanity, War crimes (Mass murder of civilian population & POWs, rape, torture, looting) | General Shunroku Hata, commander, China Expeditionary Army, Imperial Japanese Army. | War crimes were committed including mass rape, torture, looting, arson, the killing of civilians and prisoners of war.[92][93][94] |

| Manila massacre | Crimes against humanity (mass murder of civilians) | General Tomoyuki Yamashita (and Chief of Staff Akira Mutō) | As commander of the 14th Area Army of Japan in the Philippines, General Yamashita failed to stop his troops from killing over 100,000 Filipinos in Manila[95] while fighting with both native resistance forces and elements of the Sixth U.S. Army during the capture of the city in February 1945.[citation needed]

Yamashita pleaded inability to act and lack of knowledge of the massacre, due to his commanding other operations in the area. The defense failed, establishing the Yamashita Standard, which holds that a commander who makes no meaningful effort to uncover and stop atrocities is as culpable as if he had ordered them. His chief of staff Akira Mutō was condemned by the Tokyo tribunal.[citation needed] |

| Wake Island Massacre | Crimes against humanity (murder of civilians) | Sakaibara executed 19 June 1947; subordinate, Lieutenant-Commander Tachibana sentenced to death – later commuted to life imprisonment; two other officers committed suicide before they could be tried, but left statements behind incriminating Sakaibara | 98 US civilians killed on Wake Island 7 October 1943 on the order of IJN Naval Captain Shigematsu Sakaibara |

| Unit 100 [citation needed] | War crimes; use of poisons as weapons (biological warfare experiments on humans) | Two members of Unit 100, Senior Sergeant Mitomo Kazuo and Lieutenant Hirazakura Zensaku, were prosecuted at the Khabarovsk war crimes trials and received prison sentences | (Description/notes missing) |

| Unit 731 | Crimes against humanity; war crimes; crime of torture; Use of poisons as weapons (biological warfare testing, manufacturing, and use) | 12 members of the Kantogun were found guilty for the manufacture and use of biological weapons. Including: General Yamada Otsuzo, former Commander-in-Chief of the Kwantung Army and Major General Kawashima Kiyoshi, former Chief of Unit 731. | During this biological and chemical weapons' program over 10,000 were experimented on without anesthetic and as many as 200,000 died throughout China. The Soviet Union tried some members of Unit 731 at the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials. However, those who surrendered to the Americans were never brought to trial as General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, secretly granted immunity to the physicians of Unit 731 in exchange for providing the United States with their research on biological weapons.[96] |

| Unit 8604 [citation needed] | War crimes; Use of poisons as weapons (biological warfare experiments on humans) | No prosecutions | (Description/notes missing) |

| Unit 9420 [citation needed] | War crimes; Use of poisons as weapons (biological warfare experiments on humans) | No prosecutions | (Description/notes missing) |

| Unit Ei 1644[citation needed] | War crimes; Use of poisons as weapons; crime of torture (Human vivisection & chemical and biological weapon testing on humans) | No prosecutions | Unit 1644 conducted tests to determine human susceptibility to a variety of harmful stimuli ranging from infectious diseases to poison gas. It was the largest germ experimentation center in China. Unit 1644 regularly carried out human vivisections as well as infecting humans with cholera, typhus, and bubonic plague.[citation needed] |

| Construction of Burma-Thai Railway, the "Death Railway" [citation needed] | War crimes; Crimes against humanity (Crime of Slaving) | 111 Japanese military officials were tried for war crimes for their brutality during the construction of the railway. Thirty-two of them were sentenced to death. | The estimated total number of civilian labourers and POWs who died during construction is about 160,000.[citation needed] |

| Comfort women | Crimes against humanity; (Crime of Slaving; mass rape) | No prosecutions | Up to around 200,000 women were forced to work in Japanese military brothels.[97] |

| Sandakan Death Marches | Crimes against humanity (Crime of Slaving), Crime of torture, War crimes (torture and murder of civilian slave laborers and POWs) | Three Allied POWs survived to give evidence at war crimes trials in Tokyo and Rabaul. Hoshijima Susumi, Watanabe Genzo, Masao Baba, and Takakuwa Takuo were found guilty and executed for their involvement. | Over 6,000 Indonesian civilian slave laborers and POWs died. |

| War Crimes in Manchukuo | Crimes against humanity (Crime of Slaving) | Kōa-in | According to historian Zhifen Ju, more than 10 million Chinese civilians were mobilised by the Imperial Japanese Army for slave labor in Manchukuo under the supervision of the Kōa-in.[98] |

| Kaimingye germ weapon attack [citation needed] | War crimes, Use of poisons as weapons (Use of biological weapons) | No prosecutions | These bubonic plague attacks killing hundreds were a joint Unit 731 and Unit Ei 1644 endeavor. |

| Alleged Changde Bacteriological Weapon Attack April and May 1943 | War crimes; Use of poisons as weapons (Use of chemical and biological weapons in massacre of civilians) | Prosecutions at the Khabarovsk War Crimes Trials | Chemical weapons supplied by Unit 516. Bubonic plague and poison gas were used against civilians in Chengde, followed by further massacres and burning of the city.[99] Witold Urbanowicz, a Polish pilot fighting in China, estimated that nearly 300,000 civilians alone died in the battle.[citation needed] |

Crimes perpetrated by Romania

| Incident | type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iași pogrom[100] | Crimes against humanity; crime of genocide | 57 people were tried and sentenced in the People's Tribunals Iaşi trial[101] including General Emanoil Leoveanu, General Gheorghe Barozzi, General Stamatiu, former Iași Prefect Colonel Coculescu, former Iași Mayor Colonel Captaru, and Gavrilovici Constantin (former driver at the Iași bus depot). | resulted in the murder of at least 13,266 Jews |

| Odessa massacre[102] | Crimes against humanity; crime of genocide | 28 people were tried and sentenced in the People's Tribunals Odessa trial[101] including General Nicolae Macici | The mass murder of Jewish and Romani population of Odessa and surrounding towns in Transnistria (now in Ukraine) during the autumn of 1941 and winter of 1942 while under Romanian control. Depending on the accepted terms of reference and scope, the Odessa massacre refers either to the events of 22–24 October 1941 in which some 25,000 to 34,000 Jews were shot or burned, or to the murder of well over 100,000 Ukrainian Jews in the town and the areas between the Dniester and Bug rivers, during the Romanian and German occupation. In the same days, Germans and Romanians killed about 15,000 Romani people.[citation needed] |

| Aita Seaca massacre[103] | War crime | Gavril Olteanu | Retaliation by Romanian paramilitaries for the killing of 20 Romanian soldiers by ethnic Hungarian locals on 4 September 1944. Eleven ethnic Hungarian civilians executed on 26 September 1944.[citation needed] |

Crimes perpetrated by the Chetniks

Chetnik ideology revolved around the notion of a Greater Serbia within the borders of Yugoslavia, to be created out of all territories in which Serbs were found, even if the numbers were small. A directive dated 20 December 1941, addressed to newly appointed commanders in Montenegro, Major Đorđije Lašić and Captain Pavle Đurišić, outlined, among other things, the cleansing of all non-Serb elements in order to create a Greater Serbia:[104]

- The struggle for the liberty of our whole nation under the scepter of His Majesty King Peter II;

- the creation of a Great Yugoslavia and within it of a Great Serbia which is to be ethnically pure and is to include Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Srijem, the Banat, and Bačka;

- the struggle for the inclusion into Yugoslavia of all still unliberated Slovene territories under the Italians and Germans (Trieste, Gorizia, Istria, and Carinthia) as well as Bulgaria, and northern Albania with Skadar;

- the cleansing of the state territory of all national minorities and a-national elements;

- the creation of contiguous frontiers between Serbia and Montenegro, as well as between Serbia and Slovenia by cleansing the Muslim population from Sandžak and the Muslim and Croat populations from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

— Directive of 20 December 1941[104]

The Chetniks systemically massacred Muslims in villages that they captured.[105] In late autumn of 1941 the Italians handed over the towns of Višegrad, Goražde, Foča and the surrounding areas, in south-east Bosnia to the Chetniks to run as a puppet administration and NDH forces were compelled by the Italians to withdraw from there. After the Chetniks gained control of Goražde on 29 November 1941, they began a massacre of Home Guard prisoners and NDH officials that became a systematic massacre of the local Muslim civilian population.[106]

Several hundred Muslims were murdered and their bodies were left hanging in the town or thrown into the Drina river.[106] On 5 December 1941, the Chetniks received the town of Foča from the Italians and proceeded to massacre around 500 Muslims.[106] Additional massacres against the Muslims in the area of Foča took place in August 1942. In total, more than 2000 people were killed in Foča.[107]

In early January, Chetniks entered Srebrenica and killed around 1000 Muslim civilians there and in nearby villages. Around the same time the Chetniks made their way to Višegrad where deaths were reportedly in the thousands.[108] Massacres continued in the following months in the region.[109] In the village of Žepa alone about three hundred were killed in late 1941.[109] In early January, Chetniks massacred fifty-four Muslims in Čelebić and burned down the village. On 3 March, Chetniks burned forty-two Muslim villagers to death in Drakan.[108]

In early January 1943, and again in early February, Montenegrin Chetnik units were ordered to carry out "cleansing actions" against Muslims, first in the Bijelo Polje county in Sandžak and then in February in the Čajniče county and part of Foča county in southeastern Bosnia, and in part of the Pljevlja county in Sandžak.[110]

Pavle Đurišić, the officer in charge of these operations, reported to Mihailović, Chief of Staff of the Supreme Command, that on 10 January 1943: "thirty-three Muslim villages had been burned down, and 400 Muslim fighters (members of the Muslim self-protection militia supported by the Italians) and about 1,000 women and children had been killed, as against 14 Chetnik dead and 26 wounded".[110]

In another report sent by Đurišić dated 13 February 1943, he reported that: "Chetniks killed about 1,200 Muslim fighters and about 8,000 old people, women, and children; Chetnik losses in the action were 22 killed and 32 wounded".[110] He added that "during the operation the total destruction of the Muslim inhabitants was carried out regardless of sex and age".[111] The total number of deaths caused by the anti-Muslim operations between January and February 1943 is estimated at 10,000.[110] The casualty rate would have been higher had a great number of Muslims not already fled the area, most to Sarajevo, when the February action began.[110] According to a statement from the Chetnik Supreme Command from 24 February 1943, these were countermeasures taken against Muslim aggressive activities; however, all circumstances show that these massacres were committed in accordance with implementing the directive of 20 December 1941.[107]

Actions against the Croats were of a smaller scale but comparable in action.[112] In early October 1942 in the village of Gata, where an estimated 100 people were killed and many homes burnt in reprisal taken for the destruction of roads in the area carried out on the Italians' account.[107] That same month, formations under the command of Petar Baćović and Dobroslav Jevđević, who were participating in the Italian Operation Alfa in the area of Prozor, massacred over 500 Croats and Muslims and burnt numerous villages.[107] Baćović noted that "Our Chetniks killed all men 15 years of age or older. ... Seventeen villages were burned to the ground."[113] Mario Roatta, commander of the Italian Second Army, objected to these "massive slaughters" of noncombatant civilians and threatened to halt Italian aid to the Chetniks if they did not end.[113]

Crimes perpetrated by the Ustashas

The Ustaša intended to create an ethnically "pure" Greater Croatia, and they viewed those Serbs then living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina as the biggest obstacle to this goal. Ustasha ministers Mile Budak, Mirko Puk and Milovan Žanić declared in May 1941 that the goal of the new Ustasha policy was an ethnically pure Croatia. The strategy to achieve their goal was:[114][115]

- One-third of the Serbs were to be killed

- One-third of the Serbs were to be expelled

- One-third of the Serbs were to be forcibly converted to Catholicism

The Independent State of Croatia government cooperated with Nazi Germany in the Holocaust and exercised their own version of the genocide against Serbs, as well as Jews and Gypsies (Roma) inside its borders. State policy towards Serbs had first been declared in the words of Milovan Žanić, a minister of the NDH Legislative council, on 2 May 1941:

This country can only be a Croatian country, and there is no method we would hesitate to use in order to make it truly Croatian and cleanse it of Serbs, who have for centuries endangered us and who will endanger us again if they are given the opportunity.[116]

According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center (citing the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust), "Ustasa terrorists killed 500,000 Serbs, expelled 250,000 and forced 250,000 to convert to Roman Catholicism. They murdered thousands of Jews and Gypsies."[117] The execution methods used by the Ustasha were particularly brutal and sadistic and often included torture, dismemberment or decapitation.[118] A Gestapo report to Heinrich Himmler from 1942 stated, "The Ustaše committed their deeds in a bestial manner not only against males of conscript age but especially against helpless old people, women and children."[119]

Numerous concentration camps were built in the NDH, most notably Jasenovac, the largest, where around 100,000 Serbs, Jews, Roma, as well as a number of Croatian and Muslim political dissidents, died, mostly from torture and starvation.[120] It was established in August 1941 and not dismantled until April 1945, shortly before the end of the war. Jasenovac was a complex of five subcamps and three smaller camps spread out over 240 square kilometres (93 sq mi), in relatively close proximity to each other, on the bank of the Sava river.[121] Most of the camp was at Jasenovac, about 100 km (62 mi) southeast of Zagreb. The complex also included large grounds at Donja Gradina directly across the Sava River, the Jastrebarsko children's camp to the northwest, and the Stara Gradiška camp (Jasenovac V) for women and children to the southeast.[citation needed]

Unlike Nazi camps, most murders at Jasenovac were done manually using hammers, axes, knives and other implements.[122] According to testimony, on the night of 29 August 1942, guards at the camp organised a competition to see who could slaughter the most inmates, with guard and former Franciscan priest Petar Brzica winning by cutting the throats of 1,360 inmates.[122] A special knife called a "Srbosjek" (Serb-cutter) was designed for the slaughtering of prisoners.[123] Prisoners were sometimes tied with barbed wire, then taken to a ramp near to the Sava River where weights were placed on the wires, their throats and stomachs slashed before their bodies were dumped into the river.[122] After unsuccessful experiments with gas vans, camp commander Vjekoslav Luburić had a gas chamber built at Jasenovac V, where a considerable number of inmates were killed during a three-month experiment with sulfur dioxide and Zyklon B, but this method was abandoned due to poor construction.[124] The Ustashe cremated living inmates as well as corpses.[125][126] Other methods of torture and killing done included: inserting hot nails under finger nails, mutilating parts of the body including plucking out eyeballs, tightening chains around ones head until the skull fractured and the eyes popped and also, placing salt in open wounds.[127] Women were subjected to rape and torture,[128] including breast mutilation.[129] Pregnant women had their wombs cut out.[130]

An escape attempt on 22 April 1945 by 600 male inmates failed and only 84 male prisoners escaped successfully.[131] The remainder and about 400 other prisoners were then murdered by Ustasha guards, despite the fact that they knew the war was ending with Germany's capitulation.[132] All the female inmates from the women's camp (more than 700) had been massacred by the guards the previous day.[132] The guards then destroyed the camp and everything associated with it was burned to the ground.[132] Other concentration camps were the Đakovo camp, Gospić camp, Jadovno camp, Kruščica camp and the Lepoglava camp.

Ustasha militias and death squads also burnt villages and killed thousands of civilian Serbs in the country-side in sadistic ways with various weapons and tools. Men, women, children were hacked to death, thrown alive into pits and down ravines, or set on fire in churches.[133] Some Serb villages near Srebrenica and Ozren were wholly massacred, while children were found impaled by stakes in villages between Vlasenica and Kladanj.[134] The Glina massacres, where thousands of Serbs were killed, are among the more notable instances of Ustasha cruelty.

Ante Pavelić, leader of the Ustasha, fled to Argentina and Spain which gave him protection, and was never extradited to stand trial for his war crimes. Pavelić died on 28 December 1959 at the Hospital Alemán in Madrid, where the Roman Catholic church had helped him to gain asylum, at the age of 70 from gunshot wounds sustained in an earlier assassination attempt by Montenegrin Blagoje Jovović.[135] Some other prominent Ustashe figures and their respective fates:

- Andrija Artuković, Croatian Minister of Interior. Died in Croatian custody.

- Mile Budak, Croatian politician and chief Ustashe ideologist. Tried and executed by Yugoslav authorities.

- Petar Brzica, Franciscan friar who won a throat-cutting contest at Jasenovac. Post-war fate unknown.

- Miroslav Filipović, camp commander and Franciscan friar notorious for his cruelty and sadism. Tried and executed by Yugoslav authorities.

- Slavko Kvaternik, Ustashe military commander-in-chief. Tried and executed by Yugoslav authorities.

- Vjekoslav "Maks" Luburić, commander of the Ustaše Defence Brigades (Ustaška Odbrana) and Jasenovac camp. Murdered in Spain.

- Dinko Šakić, Ustashe commander of Jasenovac. Fled to Argentina, extradited to Croatia for trial in 1998. Sentenced to 20 years and died in prison in 2008.

Most Ustashe fled the country following the war, mainly with the help of Father Krunoslav Draganović, secretary of the College of Sian Girolamo who helped Ustasha fugitives immigrate illegally to South America.[136]

Crimes perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists

The Ukrainian OUN-B group, along with their military force—Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA)—are responsible for a genocide on the Polish population in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. Starting in March 1943, with its peak in the summer 1943, as many as 80,000–100,000 were killed. Although the main target were Poles, many Jews, Czechs and those Ukrainians unwilling to participate in the crimes, were massacred as well. Lacking good armament and ammunition, UPA members commonly used tools such as axes and pitchforks for the slaughter. As a result of these massacres, almost the entire non-Ukrainian population of Volhynia was either killed or forced to flee.[citation needed]

UPA commanders responsible for the genocide:

- Roman Shukhevych – general of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. As a leader of the UPA he was to be aware and to approve the project of ethnic cleansing in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

- Dmytro Klyachkivsky – colonel of the UPA. He gave the order "to wipe out an entire Polish male population between 16 and 60 years old" (according to the research of the Ukrainian historians, this citation may be falsified by the Soviet intelligence). Klyachkivsky is regarded as the main initiator of the massacres.

- Mykola Lebed – one of the OUN leaders, and UPA fighter. By the National Archives, he is described as "Ukrainian fascist leader and suspected Nazi collaborator"

- Stepan Bandera – leader of the OUN-B. His view was to remove all Poles, who were hostile towards the OUN, and assimilate the rest of them. The role of the main architect of the massacres is often assigned to him. However, he was imprisoned in German concentration camp since 1941, so there is a strong suspicion that he wasn't fully aware of events in Volhynia.[137]

See also

References

- ^ Hutchinson, Robert (2022-09-27), "Crimes without Punishment", After Nuremberg, Yale University Press, pp. 148–190, ISBN 978-0-300-25530-0, retrieved 2024-11-01

- ^ "2 Political Crimes: The 1920s", Janus-Faced Justice, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 36–68, 1992-12-31, doi:10.1515/9780824842512-004, ISBN 978-0-8248-4251-2, retrieved 2024-07-13

- ^ "War Crimes and Their Treatment Since The Second World War". A World History of War Crimes. 2016. doi:10.5040/9781474219129.ch-007.

- ^ Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field Archived 2010-03-24 at the Wayback Machine". "Studies in Intelligence", Winter 1999–2000. Retrieved on 10 December 2005.

- ^ "Katyn documentary film". Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ Sanford, George. "Katyn And The Soviet Massacre Of 1940: Truth, Justice And Memory Archived 2021-10-17 at the Wayback Machine". Routledge, 2005.

- ^ "Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. 27 February 2004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel, eds. (2007). Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study. Lexington Books. pp. 100–1. ISBN 978-0-7391-1607-4. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ^ Hitchcock, William I. (2003). The Struggle for Europe: The Turbulent History of a Divided Continent 1945–2002. Anchor. (online excerpt). ISBN 0-385-49798-9.

- ^ A Terrible Revenge: The Ethnic Cleansing of the East European Germans, 1944–1950 Alfred-Maurice de Zayas 1994. ISBN 0-312-12159-8 (No pages cited)

- ^ Barefoot in the Rubble Elizabeth B. Walter 1997. ISBN 0-9657793-0-0 (No pages cited)

- ^ Claus-Dieter Steyer, "Stadt ohne Männer" ("City without men"), Der Tagesspiegel online 21 June 2006; viewed 11 November 2006.

- ^ Joanna Ostrowska, Marcin Zaremba (7 March 2009). ""Kobieca gehenna" (The women's ordeal)". No 10 (2695) (in Polish). Polityka. pp. 64–66. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

Dr. Marcin Zaremba Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine of Polish Academy of Sciences, the co-author of the article cited above – is a historian from Warsaw University Department of History Institute of 20th Century History (cited 196 times in Google scholar Archived 2021-01-11 at the Wayback Machine). Zaremba published a number of scholarly monographs, among them: Komunizm, legitymizacja, nacjonalizm (426 pages),[1] Archived 2021-03-02 at the Wayback Machine Marzec 1968 (274 pages), Dzień po dniu w raportach SB (274 pages), Immobilienwirtschaft (German, 359 pages), see inauthor:"Marcin Zaremba" in Google Books. Archived 2021-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

Joanna Ostrowska Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine of Warsaw, Poland, is a lecturer at Departments of Gender Studies at two universities: the Jagiellonian University of Kraków, the University of Warsaw as well as, at the Polish Academy of Sciences. She is the author of scholarly works on the subject of mass rape and forced prostitution in Poland in the Second World War (i.e. "Prostytucja jako praca przymusowa w czasie II Wojny Światowej. Próba odtabuizowania zjawiska," "Wielkie przemilczanie. Prostytucja w obozach koncentracyjnych," etc.), a recipient of Socrates-Erasmus research grant from Humboldt Universitat zu Berlin, and a historian associated with Krytyka Polityczna. - ^ Antony Beevor "They raped every German female from eight to 80" Archived 2008-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 1 May 2002.

- ^ Hartman, Sebastian (23 January 2007). "Tragedia 27.01.1945r". przyszowice.com (in Polish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ Krzyk, Józef (24 January 2007). "Dokumenty z Moskwy pomogą w rozwikłaniu zbrodni z 1945 roku". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ Ealey, Mark. "An August Storm: the Soviet-Japan Endgame in the Pacific War". Japan Focus. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "As World War II entered its final stages the belligerent powers committed one heinous act after another". History News Network. 26 February 2006. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ^ a b Judgement: Doenitz Archived 19 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine the Avalon Project at the Yale Law School

- ^ "HMS Torbay (N79)". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ Hadley, Michael L. (17 March 1995). Count Not the Dead: The Popular Image of the German Submarine. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-7735-1282-9.

- ^ "Lazarettschiffe Tübingen". Feldgrau.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Alfred M. de Zayas, Die Wehrmacht-Untersuchungsstelle für Verletzungen des Völkerrechts". Lazarettschiffe Tübingen. Lindenbaum Verlag. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Le altre stragi – Le stragi alleate e tedesche nella Sicilia del 1943–1944". www.canicatti-centrodoc.it. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Xavier Guillaume, "A Heterology of American GIs during World War II" Archived 7 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. H-US-Japan (July 2003). Access date: 4 January 2008.

- ^ James J. Weingartner "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945" Pacific Historical Review (1992)

- ^ Simon Harrison "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance" Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S) 12, 817–36 (2006)

- ^ Weingartner, James J. (1992), "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945" (PDF), Pacific Historical Review: 59, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-27, retrieved 2021-06-13 cites: "Maltreatment of Enemy Dead, June 1944, NARS, CNO", Memorandum for the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-l, June 13, 1944 for the quotation.

- ^ The wording of the ICRC copy of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Sick and Wounded Archived 2016-03-25 at the Wayback Machine states in Article 3 Archived 2016-03-26 at the Wayback Machine that "After each engagement the occupant of the field of battle shall take measures to search for the wounded and dead, and to protect them against pillage and maltreatment. ...", and Article 4 Archived 2016-03-25 at the Wayback Machine states that "... They shall further ensure that the dead are honourably interred, that their graves are respected and marked so that they may always be found. ...".

- ^ "Treaties, States parties, and Commentaries – Hague Convention (IV) on War on Land and its Annexed Regulations, 1907 – -". ihl-databases.icrc.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Morton 2016.

- ^ Foster 2000, p. 437.