The US FDA’s proposed rule on laboratory-developed tests: Impacts on clinical laboratory testing

Contents

| History of Iceland |

|---|

|

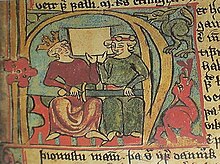

The Age of the Sturlungs or the Sturlung Era (Icelandic: Sturlungaöld [ˈstʏ(r)tluŋkaˌœlt]) was a 42-/44-year period of violent internal strife in mid-13th-century Iceland. It is documented in the Sturlunga saga. This period is marked by the conflicts of local chieftains, goðar, who amassed followers and fought wars, and is named for the Sturlungs, the most powerful family clan in Iceland at the time. The era led to the signing of the Old Covenant, which brought Iceland under the Norwegian crown.

Goðar

In the Icelandic Commonwealth, power was mostly in the hands of the goðar (local chieftains). Iceland was effectively divided into farthings (quarters). Within each farthing were nine Goði-dominions ("Goðorð"). The North farthing had an additional three dominions because of its size. There were 39 Goðorð.

The Goði-chieftains protected the farmers in their territory and exacted compensation or vengeance if their followers' rights were violated. In exchange, the farmers pledged their support to the Goði, both by voting in his favor in the Alþingi parliament and (if needed) by taking up arms against his enemies. The powers of the Goði-chieftains, however, were neither permanent nor inherited. This status came about by a combination of respect, honour, influence and wealth. The chieftains had to demonstrate their qualities as leaders, either by giving gifts to their followers or by holding great feasts. If the chieftain was seen as failing in any respect, his followers could simply choose another, more qualified Goði to support.

The greatest chieftains of the 12th and 13th century started amassing great wealth and subsuming lesser dominions. Power in the country had consolidated within the grasp of a few family clans. They were:

- The Haukdælir, of Árnesþing

- The Oddaverjar, of Rangárvellir

- The Ásbirningar, of Skagafjörður

- The Vatnsfirðingar of Ísafjörður

- The Svínfellingar of the Eastern Region

- The Sturlungar, of Hvammur in Dalir

At this time, Hákon the Old, King of Norway, was trying to extend his influence in Iceland. Many Icelandic chieftains became his vassals and were obliged to do his bidding. In exchange, they received gifts, followers and a status of respect. Consequently, the greatest Icelandic chieftains were soon affiliated with the King of Norway in one way or the other.

History

Rise of the Sturlungs

The Age of the Sturlungs began in 1220, when Snorri Sturluson, chieftain of the Sturlungar family clan and one of the great Icelandic saga writers, became a vassal of Haakon IV of Norway.[1] The king insisted that Snorri help him bring Iceland under the sovereignty of Norway. Snorri returned home, and although he soon became the country's most powerful chieftain, he did little to enforce the king's will. According to one historian, "we do not know whether [Snorri's] inactivity was due to lack of will or his conviction that the case was hopeless".[2]

In 1235, Snorri's nephew Sturla Sighvatsson also accepted vassalage under the king. Sturla was more aggressive: he sent his uncle back to Norway and started warring with the chieftains who refused to accept the king's demands. However, Sturla and his father Sighvatur were soundly defeated by Gissur Þorvaldsson, the chief of the Haukdælir, and Kolbeinn the young, chief of the Ásbirnings, in Örlygsstaðir in Skagafjörður. The Battle of Örlygsstaðir was the largest armed conflict in the history of Iceland— Sturla had 1,000 armed men, and Gissur and Kolbeinn the young had 1,200 armed men. More than 50 people were killed. After this victory, Gissur and Kolbeinn became the most powerful chieftains in the country.

Snorri Sturluson returned home to Iceland, having fallen out of favor with the king because of his support for Earl Skúli in an attempted coup. Gissur Þorvaldsson, also a vassal of the Norwegian king, received instructions to assassinate Snorri. In 1241, Gissur went with many men to Snorri's home and murdered him. Snorri's last words are said to have been "Eigi skal höggva!" (English: "Do not strike!").

In 1236, Þórður kakali Sighvatsson (the nickname kakali probably means "The Stutterer"), Snorri's brother, returned home to Iceland from abroad. He had cause for vengeance, for his brothers and father had fallen in the Battle of Örlygsstaðir. He soon showed himself to be a formidable tactician and leader. Four years later, the rule of the Ásbirnings was effectively over, after fierce battles with Þórður. The Battle of the Gulf (1244 – the only naval battle in Icelandic history with Icelanders on both sides) and the Battle of Haugsnes (1246 – the bloodiest battle in Icelandic history with about 110 fatalities) both took place during this period.

Þórður kakali and Gissur Þorvaldsson, however, did not fight each other. Both were vassals of the king of Norway, and they appealed to him as dispute mediator. The king decided in favor of Þórður and from 1247 to 1250 Þórður ruled Iceland almost alone. He died in Norway in 1256.

End of the commonwealth

In 1252, the king sent Gissur to Iceland. The followers of Þórður kakali were displeased and tried to kill him by burning his residence in Skagafjörður. Despite his influence and power, Gissur was unable to find the leader of the arsonists and was forced to return to Norway in 1254 to bear the censure of the king, who was displeased with his failure in bringing Iceland under the Norwegian throne.

Minor conflicts continued throughout Iceland. Meanwhile, Gissur was given the title of Jarl and sent home to negotiate. Only when the king had sent his special emissary, Hallvarður gullskór ("Goldenshoes"), did the Icelanders agree on Norwegian kingship. The commonwealth came to an end with the signing of the Gamli sáttmáli ("Old Covenant") agreement in 1264.

See also

References

- ^ Note, however, Sverrir Jakobsson's hesitancy in referring to the Sturlungar as an outright kinsgroup (Sverrir Jakobsson, Auðnaróðal, p. 122).

- ^ Karlsson, Gunnar (2000). The History of Iceland. p. 80.

Bibliography

- Björn Þorsteinsson: Íslensk miðaldasaga, 2. útg., Sögufélagið, Rvk. 1980.

- Byock, Jesse L.: Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, University of California Press, USA 1990.

- Gunnar Karlsson: “Frá þjóðveldi til konungsríkis", Saga Íslands II, ed. Sigurður Líndal, Hið íslenzka bókmenntafélag, Sögufélagið, Reykjavík 1975.

- ”Goðar og bændur”, s. 5–57, Saga X, Sögufélagið, Reykjavík 1972.

- Sverrir Jakobsson: Auðnaróðal. Baráttan um Ísland 1096-1281, Reykjavík: Sögufélag, 1980.

- Vísindavefurinn: Hvað var Sturlungaöld? Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine