The cannabis terpenes

Contents

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not only transmits meaning but also creates it. Models of communication are simplified overviews of its main components and their interactions. Many models include the idea that a source uses a coding system to express information in the form of a message. The message is sent through a channel to a receiver who has to decode it to understand it. The main field of inquiry investigating communication is called communication studies.

A common way to classify communication is by whether information is exchanged between humans, members of other species, or non-living entities such as computers. For human communication, a central contrast is between verbal and non-verbal communication. Verbal communication involves the exchange of messages in linguistic form, including spoken and written messages as well as sign language. Non-verbal communication happens without the use of a linguistic system, for example, using body language, touch, and facial expressions. Another distinction is between interpersonal communication, which happens between distinct persons, and intrapersonal communication, which is communication with oneself. Communicative competence is the ability to communicate well and applies to the skills of formulating messages and understanding them.

Non-human forms of communication include animal and plant communication. Researchers in this field often refine their definition of communicative behavior by including the criteria that observable responses are present and that the participants benefit from the exchange. Animal communication is used in areas like courtship and mating, parent–offspring relations, navigation, and self-defense. Communication through chemicals is particularly important for the relatively immobile plants. For example, maple trees release so-called volatile organic compounds into the air to warn other plants of a herbivore attack. Most communication takes place between members of the same species. The reason is that its purpose is usually some form of cooperation, which is not as common between different species. Interspecies communication happens mainly in cases of symbiotic relationships. For instance, many flowers use symmetrical shapes and distinctive colors to signal to insects where nectar is located. Humans engage in interspecies communication when interacting with pets and working animals.

Human communication has a long history and how people exchange information has changed over time. These changes were usually triggered by the development of new communication technologies. Examples are the invention of writing systems, the development of mass printing, the use of radio and television, and the invention of the internet. The technological advances also led to new forms of communication, such as the exchange of data between computers.

Definitions

The word communication has its root in the Latin verb communicare, which means 'to share' or 'to make common'.[1] Communication is usually understood as the transmission of information:[2] a message is conveyed from a sender to a receiver using some medium, such as sound, written signs, bodily movements, or electricity.[3] Sender and receiver are often distinct individuals but it is also possible for an individual to communicate with themselves. In some cases, sender and receiver are not individuals but groups like organizations, social classes, or nations.[4] In a different sense, the term communication refers to the message that is being communicated or to the field of inquiry studying communicational phenomena.[5]

The precise characterization of communication is disputed. Many scholars have raised doubts that any single definition can capture the term accurately. These difficulties come from the fact that the term is applied to diverse phenomena in different contexts, often with slightly different meanings.[6] The issue of the right definition affects the research process on many levels. This includes issues like which empirical phenomena are observed, how they are categorized, which hypotheses and laws are formulated as well as how systematic theories based on these steps are articulated.[7]

Some definitions are broad and encompass unconscious and non-human behavior.[8] Under a broad definition, many animals communicate within their own species and flowers communicate by signaling the location of nectar to bees through their colors and shapes.[9] Other definitions restrict communication to conscious interactions among human beings.[10] Some approaches focus on the use of symbols and signs while others stress the role of understanding, interaction, power, or transmission of ideas. Various characterizations see the communicator's intent to send a message as a central component. In this view, the transmission of information is not sufficient for communication if it happens unintentionally.[11] A version of this view is given by philosopher Paul Grice, who identifies communication with actions that aim to make the recipient aware of the communicator's intention.[12] One question in this regard is whether only successful transmissions of information should be regarded as communication.[13] For example, distortion may interfere with and change the actual message from what was originally intended.[14] A closely related problem is whether acts of deliberate deception constitute communication.[15]

According to a broad definition by literary critic I. A. Richards, communication happens when one mind acts upon its environment to transmit its own experience to another mind.[16] Another interpretation is given by communication theorists Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, who characterize communication as a transmission of information brought about by the interaction of several components, such as a source, a message, an encoder, a channel, a decoder, and a receiver.[17] The transmission view is rejected by transactional and constitutive views, which hold that communication is not just about the transmission of information but also about the creation of meaning. Transactional and constitutive perspectives hold that communication shapes the participant's experience by conceptualizing the world and making sense of their environment and themselves.[18] Researchers studying animal and plant communication focus less on meaning-making. Instead, they often define communicative behavior as having other features, such as playing a beneficial role in survival and reproduction, or having an observable response.[19]

Models of communication

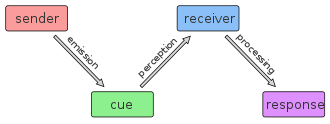

Models of communication are conceptual representations of the process of communication.[20] Their goal is to provide a simplified overview of its main components. This makes it easier for researchers to formulate hypotheses, apply communication-related concepts to real-world cases, and test predictions.[21] Due to their simplified presentation, they may lack the conceptual complexity needed for a comprehensive understanding of all the essential aspects of communication. They are usually presented visually in the form of diagrams showing the basic components and their interaction.[22]

Models of communication are often categorized based on their intended applications and how they conceptualize communication. Some models are general in the sense that they are intended for all forms of communication. Specialized models aim to describe specific forms, such as models of mass communication.[23]

One influential way to classify communication is to distinguish between linear transmission, interaction, and transaction models.[24] Linear transmission models focus on how a sender transmits information to a receiver. They are linear because this flow of information only goes in a single direction.[25] This view is rejected by interaction models, which include a feedback loop. Feedback is needed to describe many forms of communication, such as a conversation, where the listener may respond to a speaker by expressing their opinion or by asking for clarification. Interaction models represent the process as a form of two-way communication in which the communicators take turns sending and receiving messages.[26] Transaction models further refine this picture by allowing representations of sending and responding at the same time. This modification is needed to describe how the listener can give feedback in a face-to-face conversation while the other person is talking. Examples are non-verbal feedback through body posture and facial expression. Transaction models also hold that meaning is produced during communication and does not exist independently of it.[27]

All the early models, developed in the middle of the 20th century, are linear transmission models. Lasswell's model, for example, is based on five fundamental questions: "Who?", "Says what?", "In which channel?", "To whom?", and "With what effect?".[28] The goal of these questions is to identify the basic components involved in the communicative process: the sender, the message, the channel, the receiver, and the effect.[29] Lasswell's model was initially only conceived as a model of mass communication, but it has been applied to other fields as well. Some communication theorists, like Richard Braddock, have expanded it by including additional questions, like "Under what circumstances?" and "For what purpose?".[30]

The Shannon–Weaver model is another influential linear transmission model.[31] It is based on the idea that a source creates a message, which is then translated into a signal by a transmitter. Noise may interfere with and distort the signal. Once the signal reaches the receiver, it is translated back into a message and made available to the destination. For a landline telephone call, the person calling is the source and their telephone is the transmitter. The transmitter translates the message into an electrical signal that travels through the wire, which acts as the channel. The person taking the call is the destination and their telephone is the receiver.[32] The Shannon–Weaver model includes an in-depth discussion of how noise can distort the signal and how successful communication can be achieved despite noise. This can happen by making the message partially redundant so that decoding is possible nonetheless.[33] Other influential linear transmission models include Gerbner's model and Berlo's model.[34]

The earliest interaction model was developed by communication theorist Wilbur Schramm.[35] He states that communication starts when a source has an idea and expresses it in the form of a message. This process is called encoding and happens using a code, i.e. a sign system that is able to express the idea, for instance, through visual or auditory signs.[36] The message is sent to a destination, who has to decode and interpret it to understand it.[37] In response, they formulate their own idea, encode it into a message, and send it back as a form of feedback. Another innovation of Schramm's model is that previous experience is necessary to be able to encode and decode messages. For communication to be successful, the fields of experience of source and destination have to overlap.[38]

The first transactional model was proposed by communication theorist Dean Barnlund in 1970.[39] He understands communication as "the production of meaning, rather than the production of messages".[40] Its goal is to decrease uncertainty and arrive at a shared understanding.[41] This happens in response to external and internal cues. Decoding is the process of ascribing meaning to them and encoding consists in producing new behavioral cues as a response.[42]

Human

There are many forms of human communication. A central distinction is whether language is used, as in the contrast between verbal and non-verbal communication. A further distinction concerns whether one communicates with others or with oneself, as in the contrast between interpersonal and intrapersonal communication.[43] Forms of human communication are also categorized by their channel or the medium used to transmit messages.[44] The field studying human communication is known as anthroposemiotics.[45]

Verbal

Verbal communication is the exchange of messages in linguistic form, i.e., by means of language.[46] In colloquial usage, verbal communication is sometimes restricted to oral communication and may exclude writing and sign language. However, in academic discourse, the term is usually used in a wider sense, encompassing any form of linguistic communication, whether through speech, writing, or gestures.[47] Some of the challenges in distinguishing verbal from non-verbal communication come from the difficulties in defining what exactly language means. Language is usually understood as a conventional system of symbols and rules used for communication. Such systems are based on a set of simple units of meaning that can be combined to express more complex ideas. The rules for combining the units into compound expressions are called grammar. Words are combined to form sentences.[48]

One hallmark of human language, in contrast to animal communication, lies in its complexity and expressive power. Human language can be used to refer not just to concrete objects in the here-and-now but also to spatially and temporally distant objects and to abstract ideas.[49] Humans have a natural tendency to acquire their native language in childhood. They are also able to learn other languages later in life as second languages. However, this process is less intuitive and often does not result in the same level of linguistic competence.[50] The academic discipline studying language is called linguistics. Its subfields include semantics (the study of meaning), morphology (the study of word formation), syntax (the study of sentence structure), pragmatics (the study of language use), and phonetics (the study of basic sounds).[51]

A central contrast among languages is between natural and artificial or constructed languages. Natural languages, like English, Spanish, and Japanese, developed naturally and for the most part unplanned in the course of history. Artificial languages, like Esperanto, Quenya, C++, and the language of first-order logic, are purposefully designed from the ground up.[52] Most everyday verbal communication happens using natural languages. Central forms of verbal communication are speech and writing together with their counterparts of listening and reading.[53] Spoken languages use sounds to produce signs and transmit meaning while for writing, the signs are physically inscribed on a surface.[54] Sign languages, like American Sign Language and Nicaraguan Sign Language, are another form of verbal communication. They rely on visual means, mostly by using gestures with hands and arms, to form sentences and convey meaning.[55]

Verbal communication serves various functions. One key function is to exchange information, i.e. an attempt by the speaker to make the audience aware of something, usually of an external event. But language can also be used to express the speaker's feelings and attitudes. A closely related role is to establish and maintain social relations with other people. Verbal communication is also utilized to coordinate one's behavior with others and influence them. In some cases, language is not employed for an external purpose but only for entertainment or personal enjoyment.[56] Verbal communication further helps individuals conceptualize the world around them and themselves. This affects how perceptions of external events are interpreted, how things are categorized, and how ideas are organized and related to each other.[57]

Non-verbal

Non-verbal communication is the exchange of information through non-linguistic modes, like facial expressions, gestures, and postures.[58] However, not every form of non-verbal behavior constitutes non-verbal communication. Some theorists, like Judee Burgoon, hold that it depends on the existence of a socially shared coding system that is used to interpret the meaning of non-verbal behavior.[59] Non-verbal communication has many functions. It frequently contains information about emotions, attitudes, personality, interpersonal relations, and private thoughts.[60]

Non-verbal communication often happens unintentionally and unconsciously, like sweating or blushing, but there are also conscious intentional forms, like shaking hands or raising a thumb.[61] It often happens simultaneously with verbal communication and helps optimize the exchange through emphasis and illustration or by adding additional information. Non-verbal cues can clarify the intent behind a verbal message.[62] Using multiple modalities of communication in this way usually makes communication more effective if the messages of each modality are consistent.[63] However, in some cases different modalities can contain conflicting messages. For example, a person may verbally agree with a statement but press their lips together, thereby indicating disagreement non-verbally.[64]

There are many forms of non-verbal communication. They include kinesics, proxemics, haptics, paralanguage, chronemics, and physical appearance.[65] Kinesics studies the role of bodily behavior in conveying information. It is commonly referred to as body language, even though it is, strictly speaking, not a language but rather non-verbal communication. It includes many forms, like gestures, postures, walking styles, and dance.[66] Facial expressions, like laughing, smiling, and frowning, all belong to kinesics and are expressive and flexible forms of communication.[67] Oculesics is another subcategory of kinesics in regard to the eyes. It covers questions like how eye contact, gaze, blink rate, and pupil dilation form part of communication.[68] Some kinesic patterns are inborn and involuntary, like blinking, while others are learned and voluntary, like giving a military salute.[69]

Proxemics studies how personal space is used in communication. The distance between the speakers reflects their degree of familiarity and intimacy with each other as well as their social status.[70] Haptics examines how information is conveyed using touching behavior, like handshakes, holding hands, kissing, or slapping. Meanings linked to haptics include care, concern, anger, and violence. For instance, handshaking is often seen as a symbol of equality and fairness, while refusing to shake hands can indicate aggressiveness. Kissing is another form often used to show affection and erotic closeness.[71]

Paralanguage, also known as vocalics, encompasses non-verbal elements in speech that convey information. Paralanguage is often used to express the feelings and emotions that the speaker has but does not explicitly stated in the verbal part of the message. It is not concerned with the words used but with how they are expressed. This includes elements like articulation, lip control, rhythm, intensity, pitch, fluency, and loudness.[72] For example, saying something loudly and in a high pitch conveys a different meaning on the non-verbal level than whispering the same words. Paralanguage is mainly concerned with spoken language but also includes aspects of written language, like the use of colors and fonts as well as spatial arrangement in paragraphs and tables.[73] Non-linguistic sounds may also convey information; crying indicates that an infant is distressed, and babbling conveys information about infant health and well-being.[74]

Chronemics concerns the use of time, such as what messages are sent by being on time versus late for a meeting.[75] The physical appearance of the communicator, such as height, weight, hair, skin color, gender, clothing, tattooing, and piercing, also carries information.[76] Appearance is an important factor for first impressions but is more limited as a mode of communication since it is less changeable.[77] Some forms of non-verbal communication happen using such artifacts as drums, smoke, batons, traffic lights, and flags.[78]

Non-verbal communication can also happen through visual media like paintings and drawings. They can express what a person or an object looks like and can also convey other ideas and emotions. In some cases, this type of non-verbal communication is used in combination with verbal communication, for example, when diagrams or maps employ labels to include additional linguistic information.[79]

Traditionally, most research focused on verbal communication. However, this paradigm began to shift in the 1950s when research interest in non-verbal communication increased and emphasized its influence.[80] For example, many judgments about the nature and behavior of other people are based on non-verbal cues.[81] It is further present in almost every communicative act to some extent and certain parts of it are universally understood.[82] These considerations have prompted some communication theorists, like Ray Birdwhistell, to claim that the majority of ideas and information is conveyed this way.[83] It has also been suggested that human communication is at its core non-verbal and that words can only acquire meaning because of non-verbal communication.[84] The earliest forms of human communication, such as crying and babbling, are non-verbal.[85] Some basic forms of communication happen even before birth between mother and embryo and include information about nutrition and emotions.[86] Non-verbal communication is studied in various fields besides communication studies, like linguistics, semiotics, anthropology, and social psychology.[87]

Interpersonal

Interpersonal communication is communication between distinct people. Its typical form is dyadic communication, i.e. between two people, but it can also refer to communication within groups.[88] It can be planned or unplanned and occurs in many forms, like when greeting someone, during salary negotiations, or when making a phone call.[89] Some communication theorists, like Virginia M. McDermott, understand interpersonal communication as a fuzzy concept that manifests in degrees.[90] In this view, an exchange varies in how interpersonal it is based on several factors. It depends on how many people are present, and whether it happens face-to-face rather than through telephone or email. A further factor concerns the relation between the communicators:[91] group communication and mass communication are less typical forms of interpersonal communication and some theorists treat them as distinct types.[92]

Interpersonal communication can be synchronous or asynchronous. For asynchronous communication, the parties take turns in sending and receiving messages. This occurs when exchanging letters or emails. For synchronous communication, both parties send messages at the same time.[93] This happens when one person is talking while the other person sends non-verbal messages in response signaling whether they agree with what is being said.[94] Some communication theorists, like Sarah Trenholm and Arthur Jensen, distinguish between content messages and relational messages. Content messages express the speaker's feelings toward the topic of discussion. Relational messages, on the other hand, demonstrate the speaker's feelings toward their relation with the other participants.[95]

Various theories of the function of interpersonal communication have been proposed. Some focus on how it helps people make sense of their world and create society. Others hold that its primary purpose is to understand why other people act the way they do and to adjust one's behavior accordingly.[96] A closely related approach is to focus on information and see interpersonal communication as an attempt to reduce uncertainty about others and external events.[97] Other explanations understand it in terms of the needs it satisfies. This includes the needs of belonging somewhere, being included, being liked, maintaining relationships, and influencing the behavior of others.[98] On a practical level, interpersonal communication is used to coordinate one's actions with the actions of others to get things done.[99] Research on interpersonal communication includes topics like how people build, maintain, and dissolve relationships through communication. Other questions are why people choose one message rather than another and what effects these messages have on the communicators and their relation. A further topic is how to predict whether two people would like each other.[100]

Intrapersonal

Intrapersonal communication is communication with oneself.[101] In some cases this manifests externally, like when engaged in a monologue, taking notes, highlighting a passage, and writing a diary or a shopping list. But many forms of intrapersonal communication happen internally in the form of an inner exchange with oneself, like when thinking about something or daydreaming.[102] Closely related to intrapersonal communication is communication that takes place within an organism below the personal level, such as exchange of information between organs or cells.[103]

Intrapersonal communication can be triggered by internal and external stimuli. It may happen in the form of articulating a phrase before expressing it externally. Other forms are to make plans for the future and to attempt to process emotions to calm oneself down in stressful situations.[104] It can help regulate one's own mental activity and outward behavior as well as internalize cultural norms and ways of thinking.[105] External forms of intrapersonal communication can aid one's memory. This happens, for example, when making a shopping list. Another use is to unravel difficult problems, as when solving a complex mathematical equation line by line. New knowledge can also be internalized this way, like when repeating new vocabulary to oneself. Because of these functions, intrapersonal communication can be understood as "an exceptionally powerful and pervasive tool for thinking."[106]

Based on its role in self-regulation, some theorists have suggested that intrapersonal communication is more basic than interpersonal communication. Young children sometimes use egocentric speech while playing in an attempt to direct their own behavior. In this view, interpersonal communication only develops later when the child moves from their early egocentric perspective to a more social perspective.[107] A different explanation holds that interpersonal communication is more basic since it is first used by parents to regulate what their child does. Once the child has learned this, they can apply the same technique to themselves to get more control over their own behavior.[108]

Channels

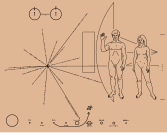

For communication to be successful, the message has to travel from the sender to the receiver. The channel is the way this is accomplished. It is not concerned with the meaning of the message but only with the technical means of how the meaning is conveyed.[109] Channels are often understood in terms of the senses used to perceive the message, i.e. hearing, seeing, smelling, touching, and tasting.[110] But in the widest sense, channels encompass any form of transmission, including technological means like books, cables, radio waves, telephones, or television.[111] Naturally transmitted messages usually fade rapidly whereas some messages using artificial channels have a much longer lifespan, as in the case of books or sculptures.[112]

The physical characteristics of a channel have an impact on the code and cues that can be used to express information. For example, typical telephone calls are restricted to the use of verbal language and paralanguage but exclude facial expressions. It is often possible to translate messages from one code into another to make them available to a different channel. An example is writing down a spoken message or expressing it using sign language.[113]

The transmission of information can occur through multiple channels at once. For example, face-to-face communication often combines the auditory channel to convey verbal information with the visual channel to transmit non-verbal information using gestures and facial expressions. Employing multiple channels can enhance the effectiveness of communication by helping the receiver better understand the subject matter.[114] The choice of channels often matters since the receiver's ability to understand may vary depending on the chosen channel. For instance, a teacher may decide to present some information orally and other information visually, depending on the content and the student's preferred learning style. This underlines the role of a media-adequate approach.[115]

Communicative competence

Communicative competence is the ability to communicate effectively or to choose the appropriate communicative behavior in a given situation.[116] It concerns what to say, when to say it, and how to say it.[117] It further includes the ability to receive and understand messages.[118] Competence is often contrasted with performance since competence can be present even if it is not exercised, while performance consists in the realization of this competence.[119] However, some theorists reject a stark contrast and hold that performance is the observable part and is used to infer competence in relation to future performances.[120]

Two central components of communicative competence are effectiveness and appropriateness.[121] Effectiveness is the degree to which the speaker achieves their desired outcomes or the degree to which preferred alternatives are realized.[122] This means that whether a communicative behavior is effective does not just depend on the actual outcome but also on the speaker's intention, i.e. whether this outcome was what they intended to achieve. Because of this, some theorists additionally require that the speaker be able to give an explanation of why they engaged in one behavior rather than another.[123] Effectiveness is closely related to efficiency, the difference being that effectiveness is about achieving goals while efficiency is about using few resources (such as time, effort, and money) in the process.[124]

Appropriateness means that the communicative behavior meets social standards and expectations.[125] Communication theorist Brian H. Spitzberg defines it as "the perceived legitimacy or acceptability of behavior or enactments in a given context".[126] This means that the speaker is aware of the social and cultural context in order to adapt and express the message in a way that is considered acceptable in the given situation.[127] For example, to bid farewell to their teacher, a student may use the expression "Goodbye, sir" but not the expression "I gotta split, man", which they may use when talking to a peer.[128] To be both effective and appropriate means to achieve one's preferred outcomes in a way that follows social standards and expectations.[129] Some definitions of communicative competence put their main emphasis on either effectiveness or appropriateness while others combine both features.[130]

Many additional components of communicative competence have been suggested, such as empathy, control, flexibility, sensitivity, and knowledge.[131] It is often discussed in terms of the individual skills employed in the process, i.e. the specific behavioral components that make up communicative competence.[132] Message production skills include reading and writing. They are correlated with the reception skills of listening and reading.[133] There are both verbal and non-verbal communication skills.[134] For example, verbal communication skills involve the proper understanding of a language, including its phonology, orthography, syntax, lexicon, and semantics.[135]

Many aspects of human life depend on successful communication, from ensuring basic necessities of survival to building and maintaining relationships.[136] Communicative competence is a key factor regarding whether a person is able to reach their goals in social life, like having a successful career and finding a suitable spouse.[137] Because of this, it can have a large impact on the individual's well-being.[138] The lack of communicative competence can cause problems both on the individual and the societal level, including professional, academic, and health problems.[139]

Barriers to effective communication can distort the message. They may result in failed communication and cause undesirable effects. This can happen if the message is poorly expressed because it uses terms with which the receiver is not familiar, or because it is not relevant to the receiver's needs, or because it contains too little or too much information. Distraction, selective perception, and lack of attention to feedback may also be responsible.[140] Noise is another negative factor. It concerns influences that interfere with the message on its way to the receiver and distort it.[141] Crackling sounds during a telephone call are one form of noise. Ambiguous expressions can also inhibit effective communication and make it necessary to disambiguate between possible interpretations to discern the sender's intention.[142] These interpretations depend also on the cultural background of the participants. Significant cultural differences constitute an additional obstacle and make it more likely that messages are misinterpreted.[143]

Other species

Besides human communication, there are many other forms of communication found in the animal kingdom and among plants. They are studied in fields like biocommunication and biosemiotics.[144] There are additional obstacles in this area for judging whether communication has taken place between two individuals. Acoustic signals are often easy to notice and analyze for scientists, but it is more difficult to judge whether tactile or chemical changes should be understood as communicative signals rather than as other biological processes.[145]

For this reason, researchers often use slightly altered definitions of communication to facilitate their work. A common assumption in this regard comes from evolutionary biology and holds that communication should somehow benefit the communicators in terms of natural selection.[146] The biologists Rumsaïs Blatrix and Veronika Mayer define communication as "the exchange of information between individuals, wherein both the signaller and receiver may expect to benefit from the exchange".[147] According to this view, the sender benefits by influencing the receiver's behavior and the receiver benefits by responding to the signal. These benefits should exist on average but not necessarily in every single case. This way, deceptive signaling can also be understood as a form of communication. One problem with the evolutionary approach is that it is often difficult to assess the impact of such behavior on natural selection.[148] Another common pragmatic constraint is to hold that it is necessary to observe a response by the receiver following the signal when judging whether communication has occurred.[149]

Animals

Animal communication is the process of giving and taking information among animals.[150] The field studying animal communication is called zoosemiotics.[151] There are many parallels to human communication. One is that humans and many animals express sympathy by synchronizing their movements and postures.[152] Nonetheless, there are also significant differences, like the fact that humans also engage in verbal communication, which uses language, while animal communication is restricted to non-verbal (i.e. non-linguistic) communication.[153] Some theorists have tried to distinguish human from animal communication based on the claim that animal communication lacks a referential function and is thus not able to refer to external phenomena. However, various observations seem to contradict this view, such as the warning signals in response to different types of predators used by vervet monkeys, Gunnison's prairie dogs, and red squirrels.[154] A further approach is to draw the distinction based on the complexity of human language, especially its almost limitless ability to combine basic units of meaning into more complex meaning structures. One view states that recursion sets human language apart from all non-human communicative systems.[155] Another difference is that human communication is frequently linked to the conscious intention to send information, which is often not discernable for animal communication.[156] Despite these differences, some theorists use the term "animal language" to refer to certain communicative patterns in animal behavior that have similarities with human language.[157]

Animal communication can take a variety of forms, including visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory communication. Visual communication happens in the form of movements, gestures, facial expressions, and colors. Examples are movements seen during mating rituals, the colors of birds, and the rhythmic light of fireflies. Auditory communication takes place through vocalizations by species like birds, primates, and dogs. Auditory signals are frequently used to alert and warn. Lower-order living systems often have simple response patterns to auditory messages, reacting either by approach or avoidance.[158] More complex response patterns are observed for higher animals, which may use different signals for different types of predators and responses. For example, some primates use one set of signals for airborne predators and another for land predators.[159] Tactile communication occurs through touch, vibration, stroking, rubbing, and pressure. It is especially relevant for parent-young relations, courtship, social greetings, and defense. Olfactory and gustatory communication happen chemically through smells and tastes, respectively.[160]

There are large differences between species concerning what functions communication plays, how much it is realized, and the behavior used to communicate.[161] Common functions include the fields of courtship and mating, parent-offspring relations, social relations, navigation, self-defense, and territoriality.[162] One part of courtship and mating consists in identifying and attracting potential mates. This can happen through various means. Grasshoppers and crickets communicate acoustically by using songs, moths rely on chemical means by releasing pheromones, and fireflies send visual messages by flashing light.[163] For some species, the offspring depends on the parent for its survival. One central function of parent-offspring communication is to recognize each other. In some cases, the parents are also able to guide the offspring's behavior.[164]

Social animals, like chimpanzees, bonobos, wolves, and dogs, engage in various forms of communication to express their feelings and build relations.[165] Communication can aid navigation by helping animals move through their environment in a purposeful way, e.g. to locate food, avoid enemies, and follow other animals. In bats, this happens through echolocation, i.e. by sending auditory signals and processing the information from the echoes. Bees are another often-discussed case in this respect since they perform a type of dance to indicate to other bees where flowers are located.[166] In regard to self-defense, communication is used to warn others and to assess whether a costly fight can be avoided.[167] Another function of communication is to mark and claim territories used for food and mating. For example, some male birds claim a hedge or part of a meadow by using songs to keep other males away and attract females.[168]

Two competing theories in the study of animal communication are nature theory and nurture theory. Their conflict concerns to what extent animal communication is programmed into the genes as a form of adaptation rather than learned from previous experience as a form of conditioning.[169] To the degree that it is learned, it usually happens through imprinting, i.e. as a form of learning that only occurs in a certain phase and is then mostly irreversible.[170]

Plants, fungi, and bacteria

Plant communication refers to plant processes involving the sending and receiving of information.[171] The field studying plant communication is called phytosemiotics.[172] This field poses additional difficulties for researchers since plants are different from humans and other animals in that they lack a central nervous system and have rigid cell walls.[173] These walls restrict movement and usually prevent plants from sending and receiving signals that depend on rapid movement.[174] However, there are some similarities since plants face many of the same challenges as animals. For example, they need to find resources, avoid predators and pathogens, find mates, and ensure that their offspring survive.[175] Many of the evolutionary responses to these challenges are analogous to those in animals but are implemented using different means.[176] One crucial difference is that chemical communication is much more prominent in the plant kingdom in contrast to the importance of visual and auditory communication for animals.[177]

In plants, the term behavior is usually not defined in terms of physical movement, as is the case for animals, but as a biochemical response to a stimulus. This response has to be short relative to the plant's lifespan. Communication is a special form of behavior that involves conveying information from a sender to a receiver. It is distinguished from other types of behavior, like defensive reactions and mere sensing.[178] Like in the field of animal communication, plant communication researchers often require as additional criteria that there is some form of response in the receiver and that the communicative behavior is beneficial to sender and receiver.[179] Biologist Richard Karban distinguishes three steps of plant communication: the emission of a cue by a sender, the perception of the cue by a receiver, and the receiver's response.[180] For plant communication, it is not relevant to what extent the emission of a cue is intentional. However, it should be possible for the receiver to ignore the signal. This criterion can be used to distinguish a response to a signal from a defense mechanism against an unwanted change like intense heat.[181]

Plant communication happens in various forms. It includes communication within plants, i.e. within plant cells and between plant cells, between plants of the same or related species, and between plants and non-plant organisms, especially in the root zone.[182] A prominent form of communication is airborne and happens through volatile organic compounds (VOCs). For example, maple trees release VOCs when they are attacked by a herbivore to warn neighboring plants, which then react accordingly by adjusting their defenses.[183] Another form of plant-to-plant communication happens through mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi form underground networks, colloquially referred to as the Wood-Wide Web, and connect the roots of different plants. The plants use the network to send messages to each other, specifically to warn other plants of a pest attack and to help prepare their defenses.[184]

Communication can also be observed for fungi and bacteria. Some fungal species communicate by releasing pheromones into the external environment. For instance, they are used to promote sexual interaction in several aquatic fungal species.[185] One form of communication between bacteria is called quorum sensing. It happens by releasing hormone-like molecules, which other bacteria detect and respond to. This process is used to monitor the environment for other bacteria and to coordinate population-wide responses, for example, by sensing the density of bacteria and regulating gene expression accordingly. Other possible responses include the induction of bioluminescence and the formation of biofilms.[186]

Interspecies

Most communication happens between members within a species as intraspecies communication. This is because the purpose of communication is usually some form of cooperation. Cooperation happens mostly within a species while different species are often in conflict with each other by competing over resources.[187] However, there are also some forms of interspecies communication.[188] This occurs especially for symbiotic relations and significantly less for parasitic or predator-prey relations.[189]

Interspecies communication plays a key role for plants that depend on external agents for reproduction.[190] For example, flowers need insects for pollination and provide resources like nectar and other rewards in return.[191] They use communication to signal their benefits and attract visitors by using distinctive colors and symmetrical shapes to stand out from their surroundings.[192] This form of advertisement is necessary since flowers compete with each other for visitors.[193] Many fruit-bearing plants rely on plant-to-animal communication to disperse their seeds and move them to a favorable location.[194] This happens by providing nutritious fruits to animals. The seeds are eaten together with the fruit and are later excreted at a different location.[195] Communication makes animals aware of where the fruits are and whether they are ripe. For many fruits, this happens through their color: they have an inconspicuous green color until they ripen and take on a new color that stands in visual contrast to the environment.[196] Another example of interspecies communication is found in the ant-plant relation.[197] It concerns, for instance, the selection of seeds by ants for their ant gardens and the pruning of exogenous vegetation as well as plant protection by ants.[198]

Some animal species also engage in interspecies communication, like apes, whales, dolphins, elephants, and dogs.[199] For example, different species of monkeys use common signals to cooperate when threatened by a common predator.[200] Humans engage in interspecies communication when interacting with pets and working animals.[201] For instance, acoustic signals play a central role in communication with dogs. Dogs can learn to react to various commands, like "sit" and "come". They can even be trained to respond to short syntactic combinations, like "bring X" or "put X in a box". They also react to the pitch and frequency of the human voice to detect emotions, dominance, and uncertainty. Dogs use a range of behavioral patterns to convey their emotions to humans, for example, in regard to aggressiveness, fearfulness, and playfulness.[202]

Computer

Computer communication concerns the exchange of data between computers and similar devices.[204] For this to be possible, the devices have to be connected through a transmission system that forms a network between them. A transmitter is needed to send messages and a receiver is needed to receive them. A personal computer may use a modem as a transmitter to send information to a server through the public telephone network as the transmission system. The server may use a modem as its receiver.[205] To transmit the data, it has to be converted into an electric signal.[206] Communication channels used for transmission are either analog or digital and are characterized by features like bandwidth and latency.[207]

There are many forms of computer networks. The most commonly discussed ones are LANs and WANs. LAN stands for local area network, which is a computer network within a limited area, usually with a distance of less than one kilometer.[208] This is the case when connecting two computers within a home or an office building. LANs can be set up using a wired connection, like Ethernet, or a wireless connection, like Wi-Fi.[209] WANs, on the other hand, are wide area networks that span large geographical regions, like the internet.[210] Their networks are more complex and may use several intermediate connection nodes to transfer information between endpoints.[211] Further types of computer networks include PANs (personal area networks), CANs (campus area networks), and MANs (metropolitan area networks).[212]

For computer communication to be successful, the involved devices have to follow a common set of conventions governing their exchange. These conventions are known as the communication protocol. They concern various aspects of the exchange, like the format of messages and how to respond to transmission errors. They also cover how the two systems are synchronized, for example, how the receiver identifies the start and end of a signal.[213] Based on the flow of informations, systems are categorized as simplex, half-duplex, and full-duplex. For simplex systems, signals flow only in one direction from the sender to the receiver, like in radio, cable television, and screens displaying arrivals and departures at airports.[214] Half-duplex systems allow two-way exchanges but signals can only flow in one direction at a time, like walkie-talkies and police radios. In the case of full-duplex systems, signals can flow in both directions at the same time, like regular telephone and internet.[215] In either case, it is often important for successful communication that the connection is secure to ensure that the transmitted data reaches only the intended destination and is not intercepted by an unauthorized third party.[216] This can be achieved by using cryptography, which changes the format of the transmitted information to make it unintelligible to potential interceptors.[217]

Human-computer communication is a closely related field that concerns topics like how humans interact with computers and how data in the form of inputs and outputs is exchanged.[218] This happens through a user interface, which includes the hardware used to interact with the computer, like a mouse, a keyboard, and a monitor, as well as the software used in the process.[219] On the software side, most early user interfaces were command-line interfaces in which the user must type a command to interact with the computer.[220] Most modern user interfaces are graphical user interfaces, like Microsoft Windows and macOS, which are usually much easier to use for non-experts. They involve graphical elements through which the user can interact with the computer, commonly using a design concept known as skeumorphism to make a new concept feel familiar and speed up understanding by mimicking the real-world equivalent of the interface object. Examples include the typical computer folder icon and recycle bin used for discarding files.[221] One aim when designing user interfaces is to simplify the interaction with computers. This helps make them more user-friendly and accessible to a wider audience while also increasing productivity.[222]

Communication studies

Communication studies, also referred to as communication science, is the academic discipline studying communication. It is closely related to semiotics, with one difference being that communication studies focuses more on technical questions of how messages are sent, received, and processed. Semiotics, on the other hand, tackles more abstract questions in relation to meaning and how signs acquire it.[223] Communication studies covers a wide area overlapping with many other disciplines, such as biology, anthropology, psychology, sociology, linguistics, media studies, and journalism.[224]

Many contributions in the field of communication studies focus on developing models and theories of communication. Models of communication aim to give a simplified overview of the main components involved in communication. Theories of communication try to provide conceptual frameworks to accurately present communication in all its complexity.[225] Some theories focus on communication as a practical art of discourse while others explore the roles of signs, experience, information processing, and the goal of building a social order through coordinated interaction.[226] Communication studies is also interested in the functions and effects of communication. It covers issues like how communication satisfies physiological and psychological needs, helps build relationships, and assists in gathering information about the environment, other individuals, and oneself.[227] A further topic concerns the question of how communication systems change over time and how these changes correlate with other societal changes.[228] A related topic focuses on psychological principles underlying those changes and the effects they have on how people exchange ideas.[229]

Communication was studied as early as Ancient Greece. Early influential theories were created by Plato and Aristotle, who stressed public speaking and the understanding of rhetoric. According to Aristotle, for example, the goal of communication is to persuade the audience.[230] The field of communication studies only became a separate research discipline in the 20th century, especially starting in the 1940s.[231] The development of new communication technologies, such as telephone, radio, newspapers, television, and the internet, has had a big impact on communication and communication studies.[232]

Today, communication studies is a wide discipline. Some works in it try to provide a general characterization of communication in the widest sense. Others attempt to give a precise analysis of one specific form of communication. Communication studies includes many subfields. Some focus on wide topics like interpersonal communication, intrapersonal communication, verbal communication, and non-verbal communication. Others investigate communication within a specific area.[233] Organizational communication concerns communication between members of organizations such as corporations, nonprofits, or small businesses. Central in this regard is the coordination of the behavior of the different members as well as the interaction with customers and the general public.[234] Closely related terms are business communication, corporate communication, and professional communication.[235] The main element of marketing communication is advertising but it also encompasses other communication activities aimed at advancing the organization's objective to its audiences, like public relations.[236] Political communication covers topics like electoral campaigns to influence voters and legislative communication, like letters to a congress or committee documents. Specific emphasis is often given to propaganda and the role of mass media.[237]

Intercultural communication is relevant to both organizational and political communication since they often involve attempts to exchange messages between communicators from different cultural backgrounds.[238] The cultural background affects how messages are formulated and interpreted and can be the cause of misunderstandings.[239] It is also relevant for development communication, which is about the use of communication for assisting in development, like aid given by first-world countries to third-world countries.[240] Health communication concerns communication in the field of healthcare and health promotion efforts. One of its topics is how healthcare providers, like doctors and nurses, should communicate with their patients.[241]

History

Communication history studies how communicative processes evolved and interacted with society, culture, and technology.[242] Human communication has a long history and the way people communicate has changed considerably over time. Many of these changes were triggered by the development of new communication technologies and had various effects on how people exchanged ideas.[243] New communication technologies usually require new skills that people need to learn to use them effectively.[244]

In the academic literature, the history of communication is usually divided into ages based on the dominant form of communication in that age. The number of ages and the precise periodization are disputed. They usually include ages for speaking, writing, and print as well as electronic mass communication and the internet.[245] According to communication theorist Marshall Poe, the dominant media for each age can be characterized in relation to several factors. They include the amount of information a medium can store, how long it persists, how much time it takes to transmit it, and how costly it is to use the medium. Poe argues that subsequent ages usually involve some form of improvement of one or more of the factors.[246]

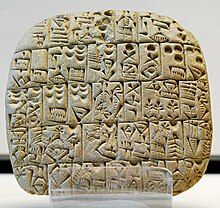

According to some scientific estimates, language developed around 40,000 years ago while others consider it to be much older. Before this development, human communication resembled animal communication and happened through a combination of grunts, cries, gestures, and facial expressions. Language helped early humans to organize themselves and plan ahead more efficiently.[247] In early societies, spoken language was the primary form of communication.[248] Most knowledge was passed on through it, often in the form of stories or wise sayings. This form does not produce stable knowledge since it depends on imperfect human memory. Because of this, many details differ from one telling to the next and are presented differently by distinct storytellers.[249] As people started to settle and form agricultural communities, societies grew and there was an increased need for stable records of ownership of land and commercial transactions. This triggered the invention of writing, which is able to solve many problems that arose from using exclusively oral communication.[250] It is much more efficient at preserving knowledge and passing it on between generations since it does not depend on human memory.[251] Before the invention of writing, certain forms of proto-writing had already developed. Proto-writing encompasses long-lasting visible marks used to store information, like decorations on pottery items, knots in a cord to track goods, or seals to mark property.[252]

Most early written communication happened through pictograms. Pictograms are graphical symbols that convey meaning by visually resembling real-world objects. The use of basic pictographic symbols to represent things like farming produce was common in ancient cultures and began around 9000 BCE. The first complex writing system including pictograms was developed around 3500 BCE by the Sumerians and is called cuneiform.[253] Pictograms are still in use today, like no-smoking signs and the symbols of male and female figures on bathroom doors.[254] A significant disadvantage of pictographic writing systems is that they need a large amount of symbols to refer to all the objects one wants to talk about. This problem was solved by the development of other writing systems. For example, the symbols of alphabetic writing systems do not stand for regular objects. Instead, they relate to the sounds used in spoken language.[255] Other types of early writing systems include logographic and ideographic writing systems.[256] A drawback of many early forms of writing, like the clay tablets used for cuneiform, was that they were not very portable. This made it difficult to transport the texts from one location to another to share information. This changed with the invention of papyrus by the Egyptians around 2500 BCE and was further improved later by the development of parchment and paper.[257]

Until the 1400s, almost all written communication was hand-written, which limited the spread of written media within society since copying texts by hand was costly. The introduction and popularization of mass printing in the middle of the 15th century by Johann Gutenberg resulted in rapid changes. Mass printing quickly increased the circulation of written media and also led to the dissemination of new forms of written documents, like newspapers and pamphlets. One side effect was that the augmented availability of written documents significantly improved the general literacy of the population. This development served as the foundation for revolutions in various fields, including science, politics, and religion.[258]

Scientific discoveries in the 19th and 20th centuries caused many further developments in the history of communication. They include the invention of telegraphs and telephones, which made it even easier and faster to transmit information from one location to another without the need to transport written documents.[259] These communication forms were initially limited to cable connections, which had to be established first. Later developments found ways of wireless transmission using radio signals. They made it possible to reach wide audiences and radio soon became one of the central forms of mass communication.[260] Various innovations in the field of photography enabled the recording of images on film, which led to the development of cinema and television.[261] The reach of wireless communication was further enhanced with the development of satellites, which made it possible to broadcast radio and television signals to stations all over the world. This way, information could be shared almost instantly everywhere around the globe.[262] The development of the internet constitutes a further milestone in the history of communication. It made it easier than ever before for people to exchange ideas, collaborate, and access information from anywhere in the world by using a variety of means, such as websites, e-mail, social media, and video conferences.[263]

See also

- Agricultural communication

- Augmentative and alternative communication

- Aviation communication

- Bias-free communication

- Communication rights

- Data transmission

- Defensive communication

- Environmental communication

- Information engineering

- Interdepartmental communication

- International communication

- Ishin-denshin

- Linguistic rights

- Military communication

- Nonviolent Communication

- Proactive communications

- Risk communication

- Scientific communication

- Small talk

- Upward communication

References

Citations

- ^

- Rosengren 2000, pp. 1–2, 1.1 On communication

- Cobley 2008, pp. 660–666

- Meinel & Sack 2014, p. 89

- ^

- ^

- Rosengren 2000, pp. 1–2, 1.1 On communication

- Munodawafa 2008, pp. 369–370

- Blackburn 1996a, Meaning and communication

- ^ Rosengren 2000, pp. 1–2, 1.1 On communication

- ^

- ^

- Dance 1970, pp. 201–202

- Craig 1999, pp. 119, 121–122, 133–134

- ^ Dance 1970, pp. 201–203

- ^ Dance 1970, pp. 207–210

- ^

- Rosengren 2000, pp. 1–2, 1.1 On communication

- Ketcham 2020, p. 100

- ^

- Dance 1970, pp. 207–209

- Rosengren 2000, pp. 1–2, 1.1 On communication

- ^

- Dance 1970, pp. 207–209

- Miller 1966, pp. 92–93

- ^ Blackburn 1996, Intention and communication

- ^ Dance 1970, pp. 208–209

- ^ Munodawafa 2008, pp. 369–370

- ^ Dance 1970, p. 209

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Barnlund 2013, p. 48

- Nicotera 2009, pp. 176, 179

- ISU staff 2016, 3.4: Functions of Verbal Communication

- Reisinger 2010, pp. 166–167

- National Communication Association 2016

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 438, transmission models

- ^

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, pp. 1, 3

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 7

- Karban 2015, p. 5

- ^ Ruben 2001, pp. 607–608, Models Of Communication

- ^

- McQuail 2008, pp. 3143–3149, Models of communication

- Narula 2006, p. 23, 1. Basic Communication Models

- ^

- McQuail 2008, pp. 3143–3149, Models of communication

- UMN staff 2016a, 1.2 The Communication Process

- Cobley & Schulz 2013, pp. 7–8, Introduction

- ^ Fiske 2011a, pp. 24, 30, 2. Other models

- ^

- McQuail 2008, pp. 3143–3149, Models of communication

- Narula 2006, p. 15, 1. Basic Communication Models

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 438, transmission models

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Fiske 2011a, pp. 30–31, 2. Other models

- Watson & Hill 2012, p. 154, Lasswell's model of communication

- Wenxiu 2015, pp. 245–249

- ^

- Steinberg 2007, pp. 52–53

- Tengan, Aigbavboa & Thwala 2021, p. 110

- Berger 1995, pp. 12–13

- ^

- Sapienza, Iyer & Veenstra 2015, §Misconception 1: it's a static model with fixed categories

- Feicheng 2022, p. 24

- Braddock 1958, pp. 88–93

- ^

- McQuail 2008, pp. 3143–3149, Models of communication

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 387, Shannon and Weaver's model

- Li 2007, pp. 5439–5442

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 387, Shannon and Weaver's model

- Fiske 2011, pp. 6–10, 1. Communication theory

- Shannon 1948, pp. 380–382

- ^

- Fiske 2011, pp. 10–15, 1. Communication theory

- Weaver 1998, pp. 4–9, 18–19, Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication

- Januszewski 2001, p. 29

- ^

- ^

- Nicotera 2009, p. 176

- Steinberg 1995, p. 18

- Bowman & Targowski 1987, pp. 25–26

- ^

- Nicotera 2009, p. 176

- Wisely 1994, pp. 90–91

- Schramm 1954, pp. 3–5, How communication works

- ^

- Schramm 1954, pp. 3–5, How communication works

- Blythe 2009, p. 188

- ^

- Wisely 1994, pp. 90–91

- Meng 2020, p. 120

- Schramm 1954, pp. 5–7, How communication works

- ^ Hamilton, Kroll & Creel 2023, p. 46

- ^

- Nicotera 2009, p. 176

- Barnlund 2013, p. 48

- ^

- Barnlund 2013, p. 47

- Watson & Hill 2015, pp. 20–22

- Lawson et al. 2019, pp. 76–77

- ^

- Watson & Hill 2015, pp. 20–22

- Dwyer 2012, p. 12

- Barnlund 2013, pp. 57–60

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 58

- Burton & Dimbleby 2002, p. 126

- Sinding & Waldstrom 2014, p. 153

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 44, channels

- Fiske 2011, pp. 17–18, 1. Communication theory

- ^

- Beynon-Davies 2010, p. 52

- Bussmann 2006, pp. 65–66

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 448

- Danesi 2000, pp. 58–59

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 448

- Kyle et al. 1988, p. 59

- Butterfield 2016, pp. 2–3

- ^

- Lyons 1981, pp. 3, 6

- Harley 2014, pp. 5–6

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, pp. 11, 13–14

- Kiggins, Comins & Gentner 2013

- ^

- Meisel 2011, p. 1

- Montrul 2004, p. 20

- ^ Harley 2014, pp. 5–6

- ^ Thomason 2006, pp. 342–345, Artificial And Natural Languages

- ^

- Champoux 2016, pp. 327–328

- Berlo 1960, pp. 41–42

- ^

- Champoux 2016, pp. 327–328

- Danesi 2009, p. 306

- Kyle et al. 1988, p. 59

- ^

- Champoux 2016, pp. 327–328

- Kyle et al. 1988, p. 59

- ^

- Danesi 2000, pp. 58–59

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 6

- Berlo 1960, pp. 7–8

- ^

- ^ Danesi 2013a, p. 492

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 690

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 107

- Giri 2009, p. 690

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 297

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 297

- Giri 2009, p. 690

- Danesi 2013a, p. 493

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 107

- ^

- Giri 2009, p. 691

- Taylor 1962, pp. 8–10

- ^ Danesi 2013a, p. 493

- ^

- Giri 2009, pp. 692–694

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 297

- ^

- Giri 2009, p. 690

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 297

- Danesi 2013a, pp. 493–495

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 693

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 692

- ^ Danesi 2013a, p. 493

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 692

- ^

- Giri 2009, p. 692

- Danesi 2013a, p. 494

- ^

- Giri 2009, p. 694

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 297

- Papa, Daniels & Spiker 2008, p. 27

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 310

- Papa, Daniels & Spiker 2008, p. 27

- ^

- ^ Giri 2009, pp. 692–693

- ^

- Giri 2009, pp. 693–694

- Danesi 2013a, p. 492

- ^ Giri 2009, pp. 693–694

- ^

- Givens & White 2021, pp. 28, 55

- Chan 2020, p. 180

- ^

- Krémer & Quijano 2017, pp. 121–122

- du Plessis et al. 2007, pp. 124–216

- Ongaro 2020, p. 216

- Jeanrond 1991, pp. 7–8

- ^

- Clough & Duff 2020, p. 323

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 244, Logocentrism

- Mills 2015, pp. 132–133

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 690

- ^ Burgoon, Manusov & Guerrero 2016, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Danesi 2013a, pp. 492–493

- Giri 2009, pp. 690–961

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 691

- ^

- ^

- Bowman, Arany & Wolfgang 2021, pp. 1455–1456

- Bornstein, Suwalsky & Breakstone 2012, pp. 113–116

- ^ Giri 2009, p. 690

- ^

- ^

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 547

- ^ McDermott 2009, pp. 547–548

- ^

- UMN staff 2016, 1.1 Communication: History and Forms

- Danesi 2013, p. 168

- McDermott 2009, pp. 547–548

- ^ Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 221

- ^ UMN staff 2016a, 1.2 The Communication Process

- ^ Trenholm & Jensen 2013, pp. 36, 361

- ^ McDermott 2009, pp. 548–549

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 549

- ^

- McDermott 2009, p. 549

- Gamble & Gamble 2019, pp. 14–16

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 546

- ^ McDermott 2009, pp. 546–547

- ^

- Ezhilarasu 2016, p. 178

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 225

- Lantolf 2009, p. 566

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 225

- Honeycutt 2014, p. 317

- ^ Vocate 2012, p. 196

- ^

- ^ Lantolf 2009, pp. 567–568

- ^ Lantolf 2009, pp. 568–569

- ^

- Lantolf 2009, p. 567

- Kreps 2012, p. 239

- ^

- Lantolf 2009, pp. 567–568

- Vocate 2012, p. 14

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 44, channels

- Fiske 2011, pp. 17–18, 1. Communication theory

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 44, channels

- Berlo 1960, pp. 63–9

- Gill & Adams 1998, pp. 35–36

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 44, channels

- Danesi 2013, p. 168

- ^ Danesi 2013, p. 168

- ^ Fiske 2011, p. 20

- ^

- Taylor 1962, pp. 8–10

- Turkington & Harris 2006, p. 140

- von Kriegstein 2011, p. 683

- ^

- Berlo 1960, p. 67

- Turkington & Harris 2006, p. 140

- Giessen 2015, pp. 43–54

- ^ Backlund & Morreale 2015, pp. 20–21

- ^ McArthur, McArthur & McArthur 2005, pp. 232–233

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 25

- ^

- Genesee 1984, p. 139

- Peterwagner 2005, p. 9

- McQuail 2008, p. 3029, Models of communication

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, pp. 17–18

- ^

- Backlund & Morreale 2015, pp. 20–21

- Spitzberg 2015, p. 241

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, pp. 18, 25

- ^

- Backlund & Morreale 2015, p. 23

- Spitzberg 2015, p. 241

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 25

- ^ Backlund & Morreale 2015, p. 23

- ^ Spitzberg 2015, p. 241

- ^

- Backlund & Morreale 2015, p. 23

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, pp. 18, 25

- ^ Spitzberg 2015, p. 241

- ^

- Backlund & Morreale 2015, p. 23

- Spitzberg 2015, p. 238

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 18

- Danesi 2009, p. 70

- ^

- Danesi 2000, pp. 59–60

- McArthur, McArthur & McArthur 2005, pp. 232–233

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 26

- ^ Backlund & Morreale 2015, pp. 20–22

- ^

- Backlund & Morreale 2015, p. 24

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, pp. 19, 24

- ^

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 24

- Spitzberg 2015, p. 242

- ^

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 25

- Berlo 1960, pp. 41–42

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 25

- ^ McArthur, McArthur & McArthur 2005, pp. 232–233

- ^ Spitzberg 2015, pp. 238–239

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 15

- ^

- Spitzberg 2015, pp. 238–239

- Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 24

- ^ Rickheit, Strohner & Vorwerg 2008, p. 24

- ^

- Buchanan & Huczynski 2017, pp. 218–219

- Fielding 2006, pp. 20–21

- ^

- ^

- van Trijp 2018, pp. 289–290

- Winner 2017, p. 29

- ^

- ^

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 45

- ^

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, pp. 1, 3

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 7

- ^ Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 128

- ^

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 128

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 3

- ^ Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 6

- ^ Ruben 2002, pp. 25–26

- ^ Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 15

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 107

- ^

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 15

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 1

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 13

- Hebb & Donderi 2013, p. 269

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 14

- Luuk & Luuk 2008, p. 206

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 5

- ^

- Houston 2019, pp. 266, 279

- Baker & Hengeveld 2012, p. 25

- ^

- Ruben 2002, p. 26

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 15

- ^

- Danesi 2000, pp. 58–59

- Hebb & Donderi 2013, p. 269

- ^

- Ruben 2002, p. 26

- Chandler & Munday 2011, p. 15

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 2

- ^ Ruben 2002, pp. 26–29

- ^

- Ruben 2002, pp. 26–27

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 2

- ^

- Ruben 2002, p. 27

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, pp. 19–20

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 3

- ^ Ruben 2002, pp. 27–28

- ^

- Ruben 2002, p. 28

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 5

- ^ Ruben 2002, pp. 28–29

- ^

- Danesi 2000, pp. 58–59

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 7

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, pp. 14–15

- ^ Karban 2015, pp. 4–5

- ^ Sebeok 1991, p. 111

- ^

- Karban 2015, pp. 1–4

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, pp. 2, 7

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 128

- ^ Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 6

- ^ Karban 2015, pp. 1–2

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 2

- ^

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 7

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 128

- ^ Karban 2015, pp. 2–4

- ^

- Karban 2015, p. 5

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 1

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 128

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 7

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 45

- ^ Baluska et al. 2006, 2. Neurobiological View of Plants and Their Body Plan

- ^

- Arimura & Pearse 2017, pp. 4–5

- Schenk & Seabloom 2010, p. 1

- Baldwin & Schultz 1983, pp. 277–279

- ^ Gilbert & Johnson 2017, pp. 84, 94

- ^

- O'Day 2012, pp. 8–9, 1. Modes of cellular communication and sexual interactions in eukaryotic microbes

- Davey 1992, pp. 951–960

- Akada et al. 1989, pp. 3491–3498

- ^

- Waters & Bassler 2005, pp. 319–320

- Demuth & Lamont 2006, p. xiii

- Berea 2017, p. 59

- ^ Berea 2017, p. 56

- ^

- Danesi 2013, pp. 167–168

- Berea 2017, p. 56

- ^

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 129

- Berea 2017, p. 61

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 109

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 110

- ^

- Karban 2015, pp. 110–112, 128

- Ketcham 2020, p. 100

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 111

- ^ Karban 2015, p. 122

- ^ Karban 2015, pp. 122–124

- ^ Karban 2015, pp. 125–126, 128

- ^

- Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 129

- Berea 2017, p. 56

- ^ Blatrix & Mayer 2010, p. 127

- ^ Berea 2017, pp. 56–57

- ^ Berea 2017, p. 61

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 157

- Berea 2017, p. 59

- Novak & Day 2018, pp. 202–203

- ^

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, pp. 157–158

- Coren 2012, p. 42

- ^ Stallings 2014, p. 40

- ^

- Stallings 2014, p. 39

- Wittmann & Zitterbart 2000, p. 1

- ^

- Stallings 2014, pp. 39–40

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 49, 175

- ^ Stallings 2014, p. 44

- ^

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 49–50

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 142, 175

- McGuire & Jenkins 2008, p. 373

- ^

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 4–5, 14

- Stallings 2014, pp. 46–48

- ^

- Nawrocki 2016, p. 340

- Grigorik 2013, p. 93

- ^

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 4–5, 14

- Shinder 2001, p. 37

- Stallings 2014, pp. 46–48

- ^

- Stallings 2014, p. 295

- Hura & Singhal 2001, p. 542

- ^

- Palmer 2012, p. 33

- Hura & Singhal 2001, pp. 4–5

- ^

- Stallings 2014, pp. 29, 41–42

- Meinel & Sack 2014, p. 129

- ^ Hura & Singhal 2001, p. 142

- ^ Hura & Singhal 2001, p. 143

- ^ Stallings 2014, pp. 41–42

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Twidale 2002, p. 414

- Riekert 1990, p. 42, What Does Knowledge Look Like?

- ^ Rao, Wang & Zhou 1996, p. 57

- ^

- Twidale 2002, p. 411

- Green, Jiang & Isaacs 2023, p. 16

- ^ Twidale 2002, pp. 411–413

- ^ Danesi 2000, pp. 58–59

- ^

- Danesi 2013, p. 181

- Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 6

- Ruben 2002a, p. 156

- Gill & Adams 1998, p. vii

- ^

- Danesi 2013, p. 181

- Cobley & Schulz 2013, pp. 7–10, Introduction

- Berger, Roloff & Ewoldsen 2010, p. 10

- ^ Cobley & Schulz 2013, pp. 31, 41–42

- ^

- Steinberg 2007, p. 18

- Gamble & Gamble 2019, pp. 14–16

- ^ Danesi 2013, p. 184

- ^ Danesi 2013, pp. 184–185

- ^ Ruben 2002a, p. 155

- ^

- Ruben 2002a, pp. 155–156

- Berger, Roloff & Ewoldsen 2010, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Ruben 2002a, pp. 155–156

- Steinberg 2007, p. 3

- Bernabo 2017, pp. 201–202, Communication History

- ^

- Ruben 2002a, pp. 155–156

- Steinberg 2007, p. 286

- Jenkins & Chen 2016, p. 506

- ^

- ^

- Hartley & Bruckmann 2008, pp. 1–2

- Mullany 2020, p. 2

- Dixon 2017, p. 204

- ^

- Sierra 2006, p. 392

- Brønn 2016, p. 360

- ^ McClelland 2008, Communication, Political

- ^ Hillstrom, Northern Lights & Magee, ECDI 2006, pp. 609–610, Intercultural communication

- ^

- Blythe 2009, pp. 177–180

- Meng 2020, p. 120

- ^

- Melkote 2003, p. 129

- Steinberg 2007, p. 301

- ^

- Steinberg 2007, p. 307

- Kreps 2002, p. 395

- ^

- Simonson et al. 2013, p. 1

- Sonderling 1995, p. 89

- ^

- Peters 2012, pp. 356–359

- Steinberg 1995, pp. 2–3

- Innis 1950, pp. 6–7

- ^

- Rowitz 2014, p. 459

- Calabrese & Sparks 2003, p. 85

- Tompkins 2023, p. 141

- ^

- Steinberg 1995, pp. 2–5

- Simonson et al. 2013, p. 1

- Simonson et al. 2013a, p. 14

- Poe 2011, p. V

- Blondheim 2016, pp. 927–928

- ^

- Poe 2011, pp. 12–13

- Peters 2012, pp. 356–359

- ^

- Steinberg 1995, p. 3

- Capstick 2020, pp. 5–6

- ^

- Danesi 2013, p. 168

- Steinberg 1995, pp. 2–3