Secure record linkage of large health data sets: Evaluation of a hybrid cloud model

Contents

-

(Top)

-

1 Etymology

-

2 Science and nature

-

3 History, art, and fashion

-

4 Symbolism and associations

-

4.1 In China

-

4.2 Light and reason

-

4.3 Gold and blond

-

4.4 Visibility and caution

-

4.5 Optimism and pleasure

-

4.6 Mayan and Italian

-

4.7 Music

-

4.8 Politics

-

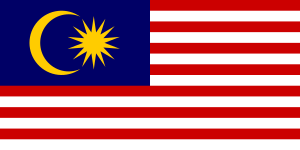

4.9 Selected national and international flags

-

4.10 Religion

-

4.11 New Age Spiritual Metaphysics

-

4.12 Sports

-

4.13 Transportation

-

4.14 Maritime signaling

-

-

5 Idioms and expressions

-

6 See also

-

7 Notes

-

8 References

| Yellow | |

|---|---|

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | 575–585[1] nm |

| Frequency | 521–512 THz |

| Hex triplet | #FFFF00 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (255, 255, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (60°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (97, 107, 86°) |

| Source | HTML/CSS[2] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Yellow is the color between green and orange on the spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a dominant wavelength of roughly 575–585 nm. It is a primary color in subtractive color systems, used in painting or color printing. In the RGB color model, used to create colors on television and computer screens, yellow is a secondary color made by combining red and green at equal intensity. Carotenoids give the characteristic yellow color to autumn leaves, corn, canaries, daffodils, and lemons, as well as egg yolks, buttercups, and bananas. They absorb light energy and protect plants from photo damage in some cases.[3] Sunlight has a slight yellowish hue when the Sun is near the horizon, due to atmospheric scattering of shorter wavelengths (green, blue, and violet).

Because it was widely available, yellow ochre pigment was one of the first colors used in art; the Lascaux cave in France has a painting of a yellow horse 17,000 years old. Ochre and orpiment pigments were used to represent gold and skin color in Egyptian tombs, then in the murals in Roman villas.[4] In the early Christian church, yellow was the color associated with the Pope and the golden keys of the Kingdom, but it was also associated with Judas Iscariot and used to mark heretics. In the 20th century, Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe were forced to wear a yellow star. In China, bright yellow was the color of the Middle Kingdom, and could be worn only by the emperor and his household; special guests were welcomed on a yellow carpet.[5]

According to surveys in Europe, Canada, the United States and elsewhere, yellow is the color people most often associate with amusement, gentleness, humor, happiness, and spontaneity; however it can also be associated with duplicity, envy, jealousy, greed, justice, and, in the U.S., cowardice.[6] In Iran it has connotations of pallor/sickness,[7] but also wisdom and connection.[8] In China and many Asian countries, it is seen as the color of royalty, nobility, respect, happiness, glory, harmony and wisdom.[9]

Etymology

The word yellow is from the Old English geolu, geolwe (oblique case), meaning "yellow, and yellowish", derived from the Proto-Germanic word gelwaz "yellow". It has the same Indo-European base, gel-, as the words gold and yell; gʰel- means both bright and gleaming, and to cry out.[10]

The English term is related to other Germanic words for yellow, namely Scots yella, East Frisian jeel, West Frisian giel, Dutch geel, German gelb, and Swedish and Norwegian gul.[11] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the oldest known use of this word in English is from The Epinal Glossary in 700.[12]

Science and nature

Optics, color printing, and computer screens

| Process Yellow (subtractive primary) | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #FFEF00 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (255, 239, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (56°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (93, 103, 80°) |

| Source | [1] CMYK |

| ISCC–NBS descriptor | Vivid greenish yellow |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

-

Mixing all three theoretically results in black, but imperfect ink formulations do not give true black, which is why an additional K component is needed.

-

An example of color printing from 1902. Combining images in yellow, magenta and cyan creates a full-color picture. This is called the CMYK color model.

-

On a computer display, yellow is created by combining green and red light at the right intensity on a black screen.

Yellow is found between green and red on the spectrum of visible light. It is the color the human eye sees when it looks at light with a dominant wavelength between 570 and 590 nanometers.

In color printing, yellow is one of the three subtractive primary colors of ink along with magenta and cyan. Together with black, they can be overlaid in the right combination to print any full color image. (See the CMYK color model). A particular yellow is used, called Process yellow (also known as "pigment yellow", "printer's yellow", and "canary yellow"). Process yellow is not an RGB color, and there is no fixed conversion from CMYK primaries to RGB. Different formulations are used for printer's ink, so there can be variations in the printed color that is pure yellow ink.

The yellow on a color television or computer screen is created in a completely different way; by combining green and red light at the right level of intensity. (See RGB color model).

Complementary colors

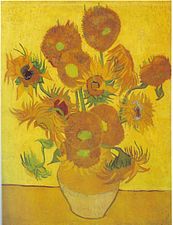

Traditionally, the complementary color of yellow is purple; the two colors are opposite each other on the color wheel long used by painters.[13] Vincent van Gogh, an avid student of color theory, used combinations of yellow and purple in several of his paintings for the maximum contrast and harmony.[14]

Hunt defines that "two colors are complementary when it is possible to reproduce the tristimulus values of a specified achromatic stimulus by an additive mixture of these two stimuli."[15] That is, when two colored lights can be mixed to match a specified white (achromatic, non-colored) light, the colors of those two lights are complementary. This definition, however, does not constrain what version of white will be specified. In the nineteenth century, the scientists Grassmann and Helmholtz did experiments in which they concluded that finding a good complement for spectral yellow was difficult, but that the result was indigo, that is, a wavelength that today's color scientists would call violet or purple. Helmholtz says "Yellow and indigo blue" are complements.[16] Grassmann reconstructs Newton's category boundaries in terms of wavelengths and says "This indigo therefore falls within the limits of color between which, according to Helmholtz, the complementary colors of yellow lie."[17]

Newton's own color circle has yellow directly opposite the boundary between indigo and violet. These results, that the complement of yellow is a wavelength shorter than 450 nm, are derivable from the modern CIE 1931 system of colorimetry if it is assumed that the yellow is about 580 nm or shorter wavelength, and the specified white is the color of a blackbody radiator of temperature 2800 K or lower (that is, the white of an ordinary incandescent light bulb). More typically, with a daylight-colored or around 5000 to 6000 K white, the complement of yellow will be in the blue wavelength range, which is the standard modern answer for the complement of yellow.

Because of the characteristics of paint pigments and use of different color wheels, painters traditionally regard the complement of yellow as the color indigo or blue-violet.

Lasers

Lasers emitting in the yellow part of the spectrum are less common and more expensive than most other colors.[18] In commercial products diode pumped solid state (DPSS) technology is employed to create the yellow light. An infrared laser diode at 808 nm is used to pump a crystal of neodymium-doped yttrium vanadium oxide (Nd:YVO4) or neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) and induces it to emit at two frequencies (281.76 THz and 223.39 THz: 1064 nm and 1342 nm wavelengths) simultaneously. This deeper infrared light is then passed through another crystal containing potassium, titanium and phosphorus (KTP), whose non-linear properties generate light at a frequency that is the sum of the two incident beams (505.15 THz); in this case corresponding to the wavelength of 593.5 nm ("yellow").[19] This wavelength is also available, though even more rarely, from a helium–neon laser. However, this not a true yellow, as it exceeds 590 nm. A variant of this same DPSS technology using slightly different starting frequencies was made available in 2010, producing a wavelength of 589 nm, which is considered a true yellow color.[20] The use of yellow lasers at 589 nm and 594 nm have recently become more widespread thanks to the field of optogenetics.[21]

Astronomy

Stars of spectral classes F and G have color temperatures that make them look "yellowish".[22] The first astronomer to classify stars according to their color was F. G. W. Struve in 1827. One of his classifications was flavae, or yellow, and this roughly corresponded to stars in the modern spectral range F5 to K0.[23] The Strömgren photometric system for stellar classification includes a 'y' or yellow filter that is centered at a wavelength of 550 nm and has a bandwidth of 20–30 nm.[24][25]

Supergiant stars are rarely yellow supergiants because F and G class supergiants are physically unstable; they are most often a transitional phase between blue supergiants and red supergiants. Some yellow supergiants, the Cepheid variables, pulsate with a period proportional to their absolute magnitude; hence, if their apparent magnitude is known, the distance to them can be calculated with great precision.[26] Cepheid variables were hence used to determine distances within and beyond the Milky Way galaxy. The most famous example is the current North Pole star, Polaris.

Biology

Autumn leaves, yellow flowers, bananas, oranges and other yellow fruits all contain carotenoids, yellow and red organic pigments that are found in the chloroplasts and chromoplasts of plants and some other photosynthetic organisms like algae, some bacteria and some fungi. They serve two key roles in plants and algae: they absorb light energy for use in photosynthesis, and they protect the green chlorophyll from photodamage.[3]

In late summer, as daylight hours shorten and temperatures cool, the veins that carry fluids into and out of the leaf are gradually closed off. The water and mineral intake into the leaf is reduced, slowly at first, and then more rapidly. It is during this time that the chlorophyll begins to decrease. As the chlorophyll diminishes, the yellow and red carotenoids become more and more visible, creating the classic autumn leaf color.

Carotenoids are common in many living things; they give the characteristic color to carrots, maize, daffodils, rutabagas, buttercups and bananas. They are responsible for the red of cooked lobsters, the pink of flamingoes and salmon and the yellow of canaries and egg yolks.

Xanthophylls are the most common yellow pigments that form one of two major divisions of the carotenoid group. The name is from Greek xanthos (ξανθος, "yellow") + phyllon (φύλλον, "leaf"). Xanthophylls are most commonly found in the leaves of green plants, but they also find their way into animals through the food they eat. For example, the yellow color of chicken egg yolks, fat, and skin comes from the feed the chickens consume. Chicken farmers understand this, and often add xanthophylls, usually lutein, to make the egg yolks more yellow.

Bananas are green when they are picked because of the chlorophyll their skin contains. Once picked, they begin to ripen; hormones in the bananas convert amino acids into ethylene gas, which stimulates the production of several enzymes. These enzymes start to change the color, texture and flavor of the banana. The green chlorophyll supply is stopped and the yellow color of the carotenoids replaces it; eventually, as the enzymes continue their work, the cell walls break down and the bananas turn brown.

-

Daffodils in Cornwall

-

Bananas, like autumn leaves, canaries and egg yolks, get their yellow color from natural pigments called carotenoids.

-

Duckling chicks

Fish

- Yellowtail is the common name for dozens of different fish species that have yellow tails or a yellow body. Most of the time, yellowtail(fish) actually refers to Japanese amberjack, a fish that lives between Japan and Hawaii.

- Yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) is a species of tuna, having bright yellow anal and second dorsal fins. Found in tropical and subtropical seas and weighing up to 200 kg (440 lb), it is caught as a replacement for depleted stocks of bluefin tuna.

- Smallmouth yellowfish (Labeobarbus aeneus) is a species of ray-finned fish in the genus Labeobarbus. It has become an invasive species in rivers of the Eastern Cape, South Africa, such as the Mbhashe River.

Insects

- The yellow-fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) is a mosquito so named because it transmits dengue fever and yellow fever, the mosquito-borne viruses.

- Yellowjackets are black-and-yellow wasps of the genus Vespula or Dolichovespula (though some can be black-and-white, the most notable of these being the bald-faced hornet, Dolichovespula maculata). They can be identified by their distinctive black-and-yellow color, small size (slightly larger than a bee), and entirely black antennae.

Trees

- Populus tremuloides is a deciduous tree native to cooler areas of North America, one of several species referred to by the common name aspen. Populus tremuloides is the most widely distributed tree in North America, being found from Canada to central Mexico.

- The yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis) is a birch species native to eastern North America, from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and southern Quebec west to Minnesota, and south in the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia. They are medium-sized deciduous trees and can reach about 20 m (66 ft) tall, trunks up to 80 cm (31 in) in diameter. The bark is smooth and yellow-bronze,[27] and the wood is extensively used for flooring, cabinetry, and toothpicks.

- The Thorny Yellowwood is an Australian rainforest tree which has deep yellow wood.

- Yellow poplar is a common name for Liriodendron, the tuliptree. The common name is inaccurate as this genus is not related to poplars.

- The Handroanthus albus is a tree with yellow flowers native to the Cerrado of Brazil.

History, art, and fashion

Prehistory

Yellow, in the form of yellow ochre pigment made from clay, was one of the first colors used in prehistoric cave art. The cave of Lascaux has an image of a horse colored with yellow estimated to be 17,300 years old.

Ancient history

In Ancient Egypt, yellow was associated with gold, which was considered to be imperishable, eternal and indestructible. The skin and bones of the gods were believed to be made of gold. The Egyptians used yellow extensively in tomb paintings; they usually used either yellow ochre or the brilliant orpiment, though it was made of arsenic and was highly toxic. A small paintbox with orpiment pigment was found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun. Men were always shown with brown faces, women with yellow ochre or gold faces.[4]

The ancient Romans used yellow in their paintings to represent gold and also in skin tones. It is found frequently in the murals of Pompeii.

-

Image of a horse colored with yellow ochre from Lascaux cave.

-

Paintings in the Tomb of Nakht in ancient Egypt (15th century BC).

-

Yellow ochre was often used in wall paintings in Ancient Roman villas and towns.

-

Byzantine art made lavish use of gold, seen in this detail of the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian from the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (before 547 AD).

-

The flag of the Paleologus dynasty of Byzantine emperors was red and gold.

Post-classical history

During the Post-Classical period, yellow became firmly established as the color of Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Jesus Christ, even though the Bible never describes his clothing. From this connection, yellow also took on associations with envy, jealousy and duplicity.

The tradition started in the Renaissance of marking non-Christian outsiders, such as Jews, with the color yellow. In 16th-century Spain, those accused of heresy and who refused to renounce their views were compelled to come before the Spanish Inquisition dressed in a yellow cape.[28]

The color yellow has been historically associated with moneylenders and finance. The National Pawnbrokers Association's logo depicts three golden spheres hanging from a bar, referencing the three bags of gold that the patron saint of pawnbroking, St. Nicholas, holds in his hands. Additionally, the symbol of three golden orbs is found in the coat of arms of the House of Medici, a famous fifteenth-century Italian dynasty of bankers and lenders.[29]

-

Saffron was sometimes used as a pigment in Medieval manuscripts, such as this page showing the murder of Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, c. 1200

-

The Kiss of Judas (1304–06) by Giotto di Bondone, followed the Medieval tradition of clothing Judas Iscariot in a yellow toga.

-

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (1560–1565)

-

Young Man in a Yellow Robe Jan Lievens, c. 1630–1631

-

The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer, c.1658

Modern history

18th and 19th centuries

The 18th and 19th century saw the discovery and manufacture of synthetic pigments and dyes, which quickly replaced the traditional yellows made from arsenic, cow urine, and other substances.

c. 1776, Jean-Honoré Fragonard painted A Young Girl Reading. She is dressed in a bright saffron yellow dress. This painting is "considered by many critics to be among Fragonard's most appealing and masterly".[30]

The 19th-century British painter J. M. W. Turner was one of the first in that century to use yellow to create moods and emotions, the way romantic composers were using music. His painting Rain, Steam, and Speed – the Great Central Railway was dominated by glowing yellow clouds.

Georges Seurat used the new synthetic colors in his experimental paintings composed of tiny points of primary colors, particularly in his famous Sunday Afternoon on the Isle de la Grand jatte (1884–86). He did not know that the new synthetic yellow pigment, zinc yellow or zinc chromate, which he used in the light green lawns, was highly unstable and would quickly turn brown.[31]

The painter Vincent van Gogh was a particular admirer of the color yellow, the color of sunshine. Writing to his sister from the south of France in 1888, he wrote, "Now we are having beautiful warm, windless weather that is very beneficial to me. The sun, a light that for lack of a better word I can only call yellow, bright sulfur yellow, pale lemon gold. How beautiful yellow is!" In Arles, Van Gogh painted sunflowers inside a small house he rented at 2 Place Lamartine, a house painted with a color that Van Gogh described as "buttery yellow". Van Gogh was one of the first artists to use commercially manufactured paints, rather than paints he made himself. He used the traditional yellow ochre, but also chrome yellow, first made in 1809; and cadmium yellow, first made in 1820.[32]

In 1895 a new popular art form began to appear in New York newspapers; the color comic strip. It took advantage of a new color printing process, which used color separation and three different colors of ink; magenta, cyan, and yellow, plus black, to create all the colors on the page. One of the first characters in the new comic strips was a humorous boy of the New York streets named Mickey Dugen, more commonly known as the Yellow Kid, from the yellow nightshirt he wore. He gave his name (and color) to the whole genre of popular, sensational journalism, which became known as "yellow journalism".

-

A Young Girl Reading, or The Reader. Jean-Honoré Fragonard, c. 1776, 32" × 25 1/2" National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway. (1844). British painter J. M. W. Turner used yellow clouds to create a mood, the way romantic composers of the time used music.

-

Georges Seurat used a new pigment, zinc yellow, in the green lawns of A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–86). He did not know that the paint would quickly deteriorate and turn brown.

-

Sunflowers (1888) by Vincent van Gogh is a fountain of yellows.

-

The Yellow Kid (1895) was one of the first comic strip characters. He gave his name to type of sensational reporting called Yellow Journalism.

-

Empress Maria Leopoldina of Brazil with her children.

-

Young woman (Marie, from Skagen, Denmark) by Michael Ancher

20th and 21st centuries

In the 20th century, yellow was revived as a symbol of exclusion, as it had been in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Jews in Nazi Germany and German-occupied countries were required to sew yellow triangles with the star of David onto their clothing.

In the 20th century, modernist painters reduced painting to its simplest colors and geometric shapes. The Dutch modernist painter Piet Mondrian made a series of paintings which consisted of a pure white canvas with a grid of vertical and horizontal black lines and rectangles of yellow, red, and blue.

Yellow was particularly valued in the 20th century because of its high visibility. Because of its ability to be seen well from greater distances and at high speeds, yellow makes for the ideal color to be viewed from moving automobiles.[29] It often replaced red as the color of fire trucks and other emergency vehicles, and was popular in neon signs, especially in Las Vegas and in China, where yellow was the most esteemed color.

In the 1960s, Pickett Brand developed the "Eye Saver Yellow" slide rule, which was produced with a specific yellow color (Angstrom 5600) that reflects long-wavelength rays and promotes optimum eye-ease to help prevent eyestrain and improve visual accuracy.[29]

The 21st century saw the use of unusual materials and technologies to create new ways of experiencing the color yellow. One example was The weather project, by Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, which was installed in the open space of the Turbine Hall of London's Tate Modern in 2003.

Eliasson used humidifiers to create a fine mist in the air via a mixture of sugar and water, as well as a semi-circular disc made up of hundreds of monochromatic lamps which radiated yellow light. The ceiling of the hall was covered with a huge mirror, in which visitors could see themselves as tiny black shadows against a mass of light.[33]

-

Yellow Room, Frederick Carl Frieseke, 1910

-

Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe were required to wear yellow badges such as this.

-

The Palácio do Planalto, official workplace of the President of Brazil, illuminated in yellow light.

Fruits, vegetables, and eggs

Many fruits are yellow when ripe, such as lemons and bananas, their color derived from carotenoid pigments. Egg yolks gain their color from xanthophylls, also a type of carotenoid pigment.

Flowers

Yellow is a common color of flowers.

-

Acacia dealbata (silver wattle)

-

Senna bicapsularis (rambling senna)

-

Galphimia glauca

(rain of gold) -

Anthyllis vulneraria (common kidneyvetch)

-

Tagetes erecta (Mexican marigold)

-

Senecio angulatus (creeping groundsel)

-

Brugmansia aurea (angel's trumpet)

Other plants

- Rapeseed (Brassica napus), also known as rape or oilseed rape, is a bright yellow flowering member of the family Brassicaceae (mustard or cabbage family).

- Goldenrod is a yellow flowering plant in the family Asteraceae.

Minerals and chemistry

- Yellowcake (also known as urania and uranic oxide) is concentrated uranium oxide, obtained through the milling of uranium ore. Yellowcake is used in the preparation of fuel for nuclear reactors and in uranium enrichment, one of the essential steps for creating nuclear weapons.

- Titan yellow (also known as clayton yellow),[34] chemical formula C

28H

19Na

2O

6S

4 has been used to determine magnesium in serum and urine, but the method is prone to interference, making the ammonium phosphate method superior when analysing blood cells, food or fecal material.[35] - Methyl yellow (p-dimethylaminoazobenzene) is a pH indicator used to determine acidity. It changes from yellow at pH 4.0 to red at pH 2.9.[36][37]

- Yellow fireworks are produced by adding sodium compounds to the firework mixture. Sodium has a strong emission at 589.3 nm (D-line), a very slightly orange-tinted yellow.

- Amongst the elements, sulfur and gold are most obviously yellow. Phosphorus, arsenic and antimony have allotropes which are yellow or whitish-yellow; fluorine and chlorine are pale yellowish gases.

- Many crystalline chemical compounds, such as 2,4-Dinitrophenol, are yellowish in color.

Pigments

- Yellow ochre (also known as Mars yellow, Pigment yellow 42, 43),[38] hydrated ferric oxide (Fe

2O

3·H

2O), is a naturally occurring pigment found in clays in many parts of the world. It is non-toxic and has been used in painting since prehistoric times.[39] - Indian yellow is a transparent, fluorescent pigment used in oil paintings and watercolors. Originally magnesium euxanthate, it was claimed to have been produced from the urine of Indian cows fed only on mango leaves.[40] It has now been replaced by synthetic Indian yellow hue.

- Naples Yellow (lead antimonate yellow) is one of the oldest synthetic pigments, derived from the mineral bindheimite and used extensively up to the 20th century.[41] It is toxic and nowadays is replaced in paint by a mixture of modern pigments.

- Cadmium Yellow (cadmium sulfide, CdS) has been used in artists' paints since the mid-19th century.[42] Because of its toxicity, it may nowadays be replaced by azo pigments.

- Chrome yellow (lead chromate, PbCrO

4), derived from the mineral crocoite, was used by artists in the earlier part of the 19th century, but has been largely replaced by other yellow pigments because of the toxicity of lead.[43] - Zinc yellow or zinc chromate is a synthetic pigment made in the 19th century, and used by the painter Georges Seurat in his pointillist paintings. He did not know that it was highly unstable, and would quickly turn brown.

- Titanium yellow (nickel antimony titanium yellow rutile, NiO·Sb

2O

5·20TiO

2) is created by adding small amounts of the oxides of nickel and antimony to titanium dioxide and heating. It is used to produce yellow paints with good white coverage and has the LBNL paint code "Y10".[44] - Gamboge is an orange-brown resin, derived from trees of the genus Garcinia, which becomes yellow when powdered.[45] It was used as a watercolor pigment in the far east from the 8th century – the name "gamboge" is derived from "Cambodia" – and has been used in Europe since the 17th century.[46]

- Orpiment, also called King's Yellow or Chinese Yellow is arsenic trisulfide (As

2S

3) and was used as a paint pigment until the 19th century when, because of its high toxicity and reaction with lead-based pigments, it was generally replaced by Cadmium Yellow.[47] - Azo dye-based pigment (a brightly colored transparent or semitransparent dye with a white pigment) is used as the colorant in most modern paints requiring either a highly saturated yellow or simplicity of color mixing. The most common is the monoazo arylide yellow family, first marketed as Hansa Yellow.

Dyes

- Curcuma longa, also known as turmeric, is a plant grown in India and Southeast Asia which serves as a dye for clothing, especially monks' robes; as a spice for curry and other dishes; and as a popular medicine. It is also used as a food coloring for mustard and other products.[48]

- Saffron, like turmeric, is one of the rare dyes that is also a spice and food colorant. It is made from the dried red stigma of the crocus sativus flower. It must be picked by hand and it takes 150 flowers to obtain a single gram of stigma, so it is extremely expensive. It probably originated in the Mediterranean or Southwest Asia, and its use was detailed in a 7th-century BC Assyrian botanical reference compiled under Ashurbanipal.[49] It was known in India at the time of the Buddha, and after his death his followers decreed that monks should wear robes the color of saffron. Saffron was used to dye the robes of the senior Buddhist monks, while ordinary monks wore robes dyed with Gamboge or Curcuma longa, also known as Turmeric.

The color of saffron comes from crocin, a red variety of carotenoid natural pigment. The color of the dyed fabric varies from deep red to orange to yellow, depending upon the type of saffron and the process. Most saffron today comes from Iran, but it is also grown commercially in Spain, Italy and Kashmir in India, and as a boutique crop in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland and other countries. In the United States, it has been cultivated by the Pennsylvania Dutch community since the early 18th century. Because of the high price of saffron, other similar dyes and spices are often sold under the name saffron; for instance, what is called Indian saffron is often really turmeric.

- Reseda luteola, also known as dyers weed, yellow weed or weld, has been used as a yellow dye from neolithic times. It grew wild along the roads and walls of Europe, and was introduced into North America, where it grows as a weed. It was used as both as a yellow dye, whose color was deep and lasting, and to dye fabric green, first by dyeing it blue with indigo, then dyeing it with reseda luteola to turn it a rich, solid and lasting green. It was the most common yellow dye in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 18th century, when it was replaced first by the bark of the quercitron tree from North America, then by synthetic dyes. It was also widely used in North Africa and in the Ottoman Empire.[50]

- Gamboge is a deep saffron to mustard yellow pigment and dye.[51] In Asia, it is frequently used to dye Buddhist monks' robes.[52][53] Gamboge is most often extracted by tapping resin from various species of evergreen trees of the family Guttiferae, which grow in Cambodia, Thailand, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.[54] "Kambuj" (Sanskrit: कंबुज) is the ancient Sanskrit name for Cambodia.

-

Orpiment was a source of yellow pigment from ancient Egypt through the 19th century, though it is highly toxic.

-

Indian yellow pigment

-

Chrome yellow was discovered in 1809.

-

Curcuma longa, also known as Turmeric, has been used for centuries in India as a dye, particularly for monk's robes. it is also commonly used as a medicine and as a spice in Indian cooking.

-

Reseda luteola, also known as dyers weed, yellow weed or weld, was the most popular source of yellow dye in Europe from the Middle Ages through the 18th century.

Food coloring

The most common yellow food coloring in use today is called Tartrazine. It is a synthetic lemon yellow azo dye.[55][56] It is also known as E number E102, C.I. 19140, FD&C yellow 5, acid yellow 23, food yellow 4, and trisodium 1-(4-sulfonatophenyl)-4-(4-sulfonatophenylazo)-5-pyrazolone-3-carboxylate.[57] It is the yellow most frequently used such processed food products as corn and potato chips, breakfast cereals such as corn flakes, candies, popcorn, mustard, jams and jellies, gelatin, soft drinks (notably Mountain Dew), energy and sports drinks, and pastries. It is also widely used in liquid and bar soap, shampoo, cosmetics and medicines. Sometimes it is mixed with blue dyes to color processed products green.

It is typically labelled on food packages as "color", "tartrazine", or "E102". In the United States, because of concerns about possible health problems related to intolerance to tartrazine, its presence must be declared on food and drug product labels.[58]

Another popular synthetic yellow coloring is Sunset Yellow FCF (also known as orange yellow S, FD&C yellow 6 and C.I. 15985) It is manufactured from aromatic hydrocarbons from petroleum. When added to foods sold in Europe, it is denoted by E number E110.[59]

Symbolism and associations

In the west, yellow is not a well-loved color. In a year 2000 survey, only 6% of respondents in Europe and America named it as their favorite color, compared with 45% for blue, 15% for green, 12% for red, and 10% for black. For 7% of respondents, it was their least favorite color.[60] Yellow is considered a color of ambivalence and contradiction. It is associated with optimism and amusement, but also with betrayal, duplicity, and jealousy.[60] However, in China and other parts of Asia, yellow is a color of virtue and nobility.

In China

Yellow has strong historical and cultural associations in China, where huáng (黃 or 黄) is the color of happiness, glory, and wisdom. Although huáng originally and occasionally still covers a range inclusive of tans and oranges,[61][62] speakers of modern Standard Mandarin tend to map their use of huáng to shades corresponding to English yellow.[63]

In Chinese symbolism, yellow, red, and green are masculine colors, while black and white are considered feminine. After the development of the theory of five elements, the Chinese reckoned various correspondences. On a five season model, late summer was characterized by yellowing leaves.[64][dubious – discuss] Yellow was taken as the color of the fifth direction of the compass, the central. China is called the Middle Kingdom; the palace of the Emperor was considered to be in the exact center of the world.[64] The legendary first emperor of China was called the Yellow Emperor and the last, Puyi (1906–67), described in his memoirs how every object which surrounded him as a child was yellow. "It made me understand from my most tender age that I was of a unique essence, and it instilled in me the consciousness of my 'celestial nature' which made me different from every other human."[65][5] The Chinese Emperor was literally considered the child of heaven, with both a political and religious role, both symbolized by yellow. After the Song dynasty, laws banned the use of certain bright yellow shades by anyone but the emperor. Distinguished visitors were honored with a yellow, not a red, carpet.

In current Chinese pop culture, the term "yellow movie" (黃色電影) refers to films and other cultural items of a pornographic nature, analogous to the English "blue movie".[66] This was the basis of the 2007 "very erotic very violent" meme, with the word "erotic" calquing Chinese "yellow".

-

The Yellow River at Sanmenxia

-

Portrait of the Jiajing Emperor from the Ming dynasty.

-

The Qianlong Emperor in court dress (18th century).

-

Yellow roofs in the Forbidden City

-

Neon lights in modern Shanghai with a predominance of red and yellow.

Light and reason

Yellow, as the color of sunlight when sun is near the horizon, is commonly associated with warmth. Yellow combined with red symbolized heat and energy. A room painted yellow feels warmer than a room painted white, and a lamp with yellow light seems more natural than a lamp with white light.

As the color of light, yellow is also associated with knowledge and wisdom. In English and many other languages, "brilliant" and "bright" mean intelligent. In Islam, the yellow color of gold symbolizes wisdom. In medieval European symbolism, red symbolized passion, blue symbolized the spiritual, and yellow symbolized reason. In many European universities, yellow gowns and caps are worn by members of the faculty of physical and natural sciences, as yellow is the color of reason and research.[67]

Gold and blond

In ancient Greece and Rome, the gods were often depicted with yellow, or blonde hair, which was described in literature as 'golden'. The color yellow was associated with the sun gods Helios and Apollo. It was fashionable in ancient Greece for men and women to dye their hair yellow, or to spend time in the sun to bleach it.[68] In ancient Rome, prostitutes were required to bleach their hair, to be easily identified, but it also became a fashionable hair color for aristocratic women, influenced by the exotic blonde hair of many of the newly conquered slaves from Gaul, Britain, and Germany.[69] However, in medieval Europe and later, the word yellow often had negative connotations; associated with betrayal, so yellow hair was more poetically called 'blond,' 'light', 'fair,' or most often "golden".[68]

Visibility and caution

Yellow is the most visible color from a distance, so it is often used for objects that need to be seen, such as fire engines, road maintenance equipment, school buses and taxicabs. It is also often used for warning signs, since yellow traditionally signals caution, rather than danger. Safety yellow is often used for safety and accident prevention information. A yellow light on a traffic signal means slow down, but not stop. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) uses Pantone 116 (a yellow hue) as their standard color implying "general warning", while the Federal Highway Administration similarly uses yellow to communicate warning or caution on highway signage.[29] A yellow penalty card in a soccer match means warning, but not expulsion.

-

In North America, school buses such as this one in Albemarle County, Virginia are required to be painted yellow.

-

A mailbox in Germany. Yellow was the color of the early postal service in the Habsburg Empire.

-

A crash tender of the Royal Danish Air Force.

-

An RAF Sea King rescue helicopter.

-

Yellow penalty card used during an association football match

Optimism and pleasure

Yellow is the color most associated with optimism and pleasure; it is a color designed to attract attention, and is used for amusement. Yellow dresses in fashion are rare, but always associated with gaiety and celebration.

-

Portrait of Madame Kuznetsova, by Ilya Repin. (1901)

-

The Ball by James Tissot (1880)

-

Yellow Dress – Paris Haute Couture Spring-Summer

-

Kuchipudi dancers

-

Singer Kylie Minogue performs at a Nobel Prize Concert

Mayan and Italian

The ancient Maya associated the color yellow with the direction South. The Maya glyph for "yellow" (k'an) also means "precious" or "ripe".[70]

"Giallo", in Italian, refers to crime stories, both fictional and real. This association began in about 1930, when the first series of crime novels published in Italy had yellow covers.

Music

- The Beatles 1966 album Revolver features the No. 1 hit, "Yellow Submarine". Subsequently, United Artists released an animated film in 1968 called Yellow Submarine, based on the music of the Beatles.

- The March 1967 album by Donovan called Mellow Yellow reached number 2 on the U.S. Billboard charts in 1966 and number 8 in the UK in early 1967. The song of the same name popularized a widely-held belief that it was possible to get high by smoking scrapings from the inside of banana peels. This rumor was actually started in 1966 by Country Joe McDonald.

- Coldplay achieved worldwide fame with their 2000 single "Yellow".

- "Yellow River" is a song recorded by the British band Christie in 1970.

- The Yellow River Piano Concerto is a piano concerto arranged by a collaboration between musicians including Yin Chengzong and Chu Wanghua. Its premiere was in 1969 during the Cultural Revolution.

Politics

- Yellow as a political color is most commonly associated with liberalism, libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism.[71][72] Contemporary political parties using yellow include the Liberal Democrats and UKIP in the United Kingdom, the SNP in Scotland, ACT in New Zealand, and Libertarian Party in the United States.

- In the United States, a yellow dog Democrat was a Southern voter who consistently voted for Democratic candidates in the late 19th and early 20th centuries because of lingering resentment against the Republicans dating back to the Civil War and Reconstruction period. Today the term refers to a hard-core Democrat, supposedly referring to a person who would vote for a "yellow dog" before voting for a Republican.

- In China the Yellow Turbans were a Daoist sect that staged an extensive rebellion during the Han dynasty.

- The 1986 People Power Revolution in the Philippines was also known as the Yellow Revolution due to the presence of yellow ribbons during the demonstrations. Liberal and pro-democracy political parties and organizations such as UNIDO, PDP-Laban, and the Liberal Party have used the color yellow. More recently, it has become a pejorative term used by some pro-Ferdinand Marcos and pro-Rodrigo Duterte against the opposition.

- In France in November and December 2018, an opposition movement called the Yellow Vests went into the streets to protest against the fiscal policies of President Emmanuel Macron. They wore yellow safety vests, which French motorists are required by law to have in their cars.[73]

Selected national and international flags

Three of the five most populous countries in the world (China and Brazil) have yellow or gold in their flag, representing about half of the world's population. While many flags use yellow, their symbolism varies widely, from civic virtue to golden treasure, golden fields, the desert, royalty, the keys to Heaven and the leadership of the Communist Party. In classic European heraldry, yellow, along with white, is one of the two metals (called gold and silver) and therefore flags following heraldic design rules must use either yellow or white to separate any of their other colors (see the rule of tincture and insignia).

-

Flag of Belgium (1831). The yellow comes from the yellow lion in the coat of arms of the Duchy of Brabant, founded in 1183–84.

-

Flag of Bhutan (1956). The Bhutan flag features Druk, the thunder dragon of Bhutanese mythology. The yellow represents civic tradition, the red the Buddhist spiritual tradition.

-

Flag of Brazil (1889). The yellow color was inherited from the flag of the Empire of Brazil (1822–1889), where it represented the color of the House of Habsburg.

-

Flag of Brunei (1956). In Southeast Asia yellow is the color of royalty. it is the color of the Sultan of Brunei, and also appears on the flag of Thailand and of Malaysia.

-

Flag of Chad (1959). The color yellow here represents the sun and the desert in the north of the country. This flag is identical to that of Romania, except that it uses a slightly darker indigo blue rather than cobalt blue.

-

Flag of the People's Republic of China (1949). The four small gold stars represent the workers, peasants, urban middle class, and rural middle class. The large star represents the Chinese Communist Party.

-

Flag of Colombia. The asymmetric design of the flag is based on the old Flag of Gran Colombia. The yellow color represents the golden treasure taken from Colombia over the centuries.

-

Flag of Germany. Black, red and yellow were the colors of the Holy Roman Emperor, and, in 1919, of the German Weimar Republic. The modern German flag was adopted in 1949.

-

Flag of Jamaica (1962). It is currently the only national flag that does not contain a shade of the colors red, white, or blue.

-

Flag of Lithuania (1918 to 1940, restored in 1989, modified in 2004). Yellow represents the sun, light and goodness.

-

Flag of Malaysia (original version, 1950, current version 1963.) The yellow crescent represents Islam, the yellow star the unity of the fourteen states of Malaysia. The red and white stripes (like the stripes on the U.S. flag) are adopted from the flag of the British East India Company.

-

Flag of Mozambique (1983). The colors are those of the Marxist Liberation Front of Mozambique, or FRELIMO, which rules the country. Yellow represents the country's mineral wealth.

-

Flag of the Philippines (1898). The yellow sun is in the middle of the triangle shape.

-

Flag of Romania (1848, and again in 1989, after the fall of the Communist regime.) Blue, yellow and red were the colors of the Wallachian uprising of 1821, and the 1848 revolution. Yellow represents justice.

-

Flag of Spain (1978). The yellow in the Spanish flag comes from the traditional Crown of Castille and the Crown of Aragon. The general design was adopted in 1785 for the Spanish Navy, to be visible from a great distance at sea.

-

Flag of Sweden (adopted 1906, but colors in use since at least the mid-16th century). The legend says that in 1157, during the First Swedish Crusade, the Swedish king Eric the Holy saw a golden cross appear in the blue sky.

-

Flag of Ukraine (1992 (originally in 1918)).

-

Flag of Vatican City (1929). The yellow color represents the golden key of the Kingdom of heaven, described in the Book of Matthew of the New Testament, and part of the Papal seal on the flag.

-

Flag of Vietnam (1955). The big gold star represents five main classes (laborers, soldiers, peasants, intellectuals and bourgeois).

Defunct flags

-

The banner of the Holy Roman Empire (15th century). The black, yellow and red colors reappeared first in 1848 and then in the 20th century in the German flag.

-

(1819) The flag of Gran Colombia, which won independence from Spain, then broke into three countries (Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador) in 1830.

-

Imperial flag of the Qing dynasty, China (1890–1912), the last dynasty of China, overthrown by the Xinhai Revolution of 1911.

-

Flag of South Vietnam (1955–75). This was the flag of the anti-communist southern part of Vietnam during the Vietnam War. It was replaced by the flag of North Vietnam after communist forces took Saigon on 30 April 1975.

-

The flag of East Germany (1959–90). It differs from the West German flag by the presence of a communist symbol in the center, and it fell out of use when Germany was reunified after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Religion

- In Buddhism, the saffron colors of robes to be worn by monks were defined by the Buddha himself and his followers in the 5th century BCE. The robe and its color is a sign of renunciation of the outside world and commitment to the order. The candidate monk, with his master, first appears before the monks of the monastery in his own clothes, with his new robe under his arm, and asks to enter the order. He then takes his vows, puts on the robes, and with his begging bowl, goes out to the world. Thereafter, he spends his mornings begging and his afternoons in contemplation and study, either in a forest, garden, or in the monastery.[74] According to Buddhist scriptures and commentaries, the robe dye is allowed to be obtained from six kinds of substances: roots and tubers, plants, bark, leaves, flowers and fruits. The robes should also be boiled in water a long time to get the correctly sober color. Saffron and ochre, usually made with dye from the curcuma longa plant or the heartwood of the jackfruit tree, are the most common colors. The so-called forest monks usually wear ochre robes and city monks saffron, though this is not an official rule.[75] The color of robes also varies somewhat among the different "vehicles", or schools of Buddhism, and by country, depending on their doctrines and the dyes available. The monks of the strict Vajrayana, or Tantric Buddhism, practiced in Tibet, wear the most colorful robes of saffron and red. The monks of Mahayana Buddhism, practiced mainly in Japan, China and Korea, wear lighter yellow or saffron, often with white or black. Monks of Hinayana Buddhism, practiced in Southeast Asia, usually wear ochre or saffron color. Monks of the forest tradition in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia wear robes of a brownish ochre, dyed from the wood of the jackfruit tree.[74][76]

- In Hinduism, the divinity Krishna is commonly portrayed dressed in yellow. Yellow and saffron are also the colors worn by sadhu, or wandering holy men in India. The Hindu almighty and divine god Lord Ganesha or Ganpati is mostly dressed with a dhotar in yellow, which is popularly known as pivla pitambar and is considered to be the most auspicious one.

- In Sikhism: The Sikh Rehat Maryada clearly states that the Nishan Sahib hoisted outside every Gurudwara should be xanthic (Basanti in Punjabi) or greyish blue (modern day Navy blue) (Surmaaee in Punjabi) color.[77][78]

- In Islam, the yellow color of gold symbolizes wisdom.

- In the religions of the islands of Polynesia, yellow is a sacred color, the color of the divine essence; the word "yellow" in the local languages is the same as the name of the curcuma longa plant, which is considered the food of the gods.[76]

- In the Roman Catholic Church, yellow symbolizes gold, and in Christian mythology the golden key to the Kingdom of Heaven, which divine Christ gave to Saint Peter. The flag of the Vatican City and the colors of the pope are yellow and white, symbolizing the gold key and the silver key. White and yellow together can also symbolize Easter, rebirth and Resurrection. Yellow also has a negative meaning, symbolizing betrayal; Judas Iscariot is usually portrayed wearing a pale yellow toga. Yellow and golden halos mark the saints in religious paintings.

- In Wicca, yellow represents intellect, inspiration, imagination, and knowledge. It is used for communication, confidence, divination, and study.[79]

-

Buddhist monks at the promotion ceremony of a monk in Thailand

-

Buddhist monks in Tibet

-

A Japanese Buddhist monk in downtown Tokyo

-

Christ giving the golden key of the kingdom heaven to Saint Peter (1481–82), by Pietro Perugino. The golden key is the symbol of the Pope.

-

Pope Benedict XVI. The Pope traditionally wears gold and white outside St. Peter's Basilica.

New Age Spiritual Metaphysics

- In the metaphysics of the New Age author, Alice A. Bailey, in her system called the Seven Rays which classifies humans into seven different metaphysical psychological types, the fourth ray of harmony through conflict is represented by the color yellow. People who have this metaphysical psychological type are said to be on the Yellow Ray."[80]

- Yellow is used to symbolically represent the third, solar plexus chakra (Manipura).[81]

- Psychics who claim to be able to observe the aura with their third eye report that someone with a yellow aura is typically someone who is in an occupation requiring intellectual acumen, such as a scientist.[82]

Sports

- In Association football (soccer), the referee shows a yellow card to indicate that a player has been officially warned because they have committed a foul or have wasted time.

- Originally in Rugby league and then later, also in Rugby Union, the referee shows a yellow card to indicate that a player has been sent to the sin bin.

- In cycle racing, the yellow jersey – or maillot jaune – is awarded to the leader in some stage races. The tradition was begun in the Tour de France where the sponsoring L'Auto newspaper (later L'Équipe) was printed on distinctive yellow newsprint.

Transportation

- In some countries, taxicabs are commonly yellow. This practice began in Chicago, where taxi entrepreneur John D. Hertz painted his taxis yellow based on a University of Chicago study alleging that yellow is the color most easily seen at a distance.[83]

- In Canada and the United States, school buses are almost uniformly painted a yellow color (often referred to as "school bus yellow") for purposes of visibility and safety,[84] and British bus operators such as FirstGroup are attempting to introduce the concept there.[85]

- "Caterpillar yellow" and "high-visibility yellow" are used for highway construction equipment.[86]

- In the rules of the road, yellow (called "amber" in Britain) is a traffic light signal meaning "slow down", "caution", or "slow speed ahead". It is intermediate between green (go) and red (stop). In railway signaling, yellow is often the color for warning, slow down, such as with distant signals.[87]

- Selective yellow is used in some automotive headlamps and fog lights to reduce the dazzling effects of rain, snow, and fog.

Maritime signaling

- In International maritime signal flags a yellow flag denotes the letter "Q".[88] It also means a ship asserts that it does not need to be quarantined.[88]

Idioms and expressions

- Yellow-belly is an American expression which means a coward.[89] The term comes from the 19th century and the exact origin is unknown, but it may refer to the color of sickness, which means a person lacks strength and stamina.[90]

- Yellow journalism is also an American term for news which present limited research to its findings.

- Yellow pages refers in various countries to directories of telephone numbers, arranged alphabetically by the type of business or service offered.

- Asian people, especially East Asians, have been racialized as yellow.[91]

- The Yellow Peril was a term used in politics and popular fiction in the late 19th and early 20th century to describe the alleged economic and cultural danger posed to Europe and America by Chinese immigration. The term was first used by Kaiser Wilhelm II in Germany in 1895, and was the subject of numerous books and later films.[92]

- Yellow fever is a slang phrase to describe an Asian race fetish.[93]

- High yellow was a term sometimes used in the early 20th century, to describe light-skinned African-Americans.

- Yellow snow, snow that is yellow from urination.

See also

Notes

- ^ Elert, Glenn (2021). "Color". The Physics Hypertextbook. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "CSS Color Module Level 3". 19 June 2018. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ a b Armstrong, G.A.; Hearst, J.E. (1996). "Carotenoids 2: Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis". FASEB J. 10 (2): 228–37. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641556. ISSN 0892-6638. PMID 8641556. S2CID 22385652. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Antiquity". Pigments through the Ages. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b Cited in Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, p. 82.

- ^ Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, pp. 69–86.

- ^ Price, Massoume (December 2001). "Culture of Iran: Festival of Fire". Iran Chamber Society. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023.

- ^ Amjadi, Maryam Ala (2012). "Shades of doubt and shapes of hope: Colors in Iranian culture". Payvand. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022.

- ^ Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, pp. 69–86

- ^ Webster's New World Dictionary of American English, Third College Edition, (1988)

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ "yellow, adj. and n". Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Retrieved 21 April 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Roelofs, Isabelle; Petillion, Fabien (2012). La couleur expliquée aux artistes. Paris: Eyrolles. ISBN 978-2-212-13486-5.

- ^ Gage, John (2006). La Couleur dans l'art. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Hunt, J. W. G. (1980). Measuring Color. Ellis Horwood Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7458-0125-4.

- ^ von Helmholtz, Hermann (1924). Physiological Optics. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-44260-0.

- ^ Grassmann, Hermann Günter (1854). "Theory of Compound Colors". Philosophical Magazine. 4: 254–64.

- ^ "Laserglow – Blue, Red, Yellow, Green Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

described as an "extremely rare yellow".

- ^ Johnson, Craig (22 March 2009). "Yellow (593.5 nm) DPSS Laser Module". The LED Museum. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "Laserglow – Blue, Red, Yellow, Green Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Laserglow – Blue, Red, Yellow, Green Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Miller, Ron (2005). Stars and Galaxies. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7613-3466-8. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Murdin, Paul (1984). Colours of the stars. CUP Archive. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-521-25714-5.

- ^ Strömgren, Bengt (1963). "Main Sequence Stars, Problems of Internal Constitution and Kinematics (George Darwin Lecture)". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 8: 8–37. Bibcode:1963QJRAS...4....8S.

- ^ Norton, Andrew; Cooper, W. Alan (2004). Observing the universe: a guide to observational astronomy and planetary science. Cambridge University Press. p. 63. Bibcode:2004ougo.book.....N. ISBN 978-0-521-60393-5.

- ^ Parsons, S. B. (1 April 1971). "Effective Temperatures, Intrinsic Colours, and Surface Gravities of Yellow Supergiants and Cepheids". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 152 (1): 121–131. doi:10.1093/mnras/152.1.121. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Beaulieu, David. "Fall Foliage of 4 Types of Birch Trees". About.com Home.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Eva Heller (2000). Psychologie de la couleur -effets et symboliques, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Karen (2010). "Yellowtown: Urban Signage, Class, and Race". Design and Culture. 2 (2): 183–198. doi:10.2752/175470710X12696138525668. S2CID 143685043.

- ^ Walker, John (1975). National Gallery of Art, Washington. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8109-0336-4.

- ^ John Gage, (1993), Colour and Culture – Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction, p. 220.

- ^ Stefano Zuffi (2012), Color in Art, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Cynthia Zarin (13 November 2006), Seeing Things. The art of Olafur Eliasson Archived 7 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine New Yorker.

- ^ "Titan Yellow". Nile Chemicals. 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ Heaton, F.W. (July 1960). "Determination of magnesium by the Titan yellow and ammonium phosphate methods". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 13 (4): 358–60. doi:10.1136/jcp.13.4.358. PMC 480095. PMID 14400446.

- ^ "para-Dimethylaminobenzene". IARC – Summaries & Evaluations. 8: 125. 1975. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ "Ph paper, Litmus paper, ph indicator, laboratory stain". GMP ChemTech Private Limited. 2003. Archived from the original on 12 November 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ "Health & Safety in the Arts". City of Tucson. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ "Pigments through the ages: Yellow ochre". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ Harley, Rosamond Drusilla (2001). Artists' Pigments c1600-1835 (2 ed.). London: Archetype Publications. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-873132-91-3. OCLC 47823825. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Pigments through the ages: Naples yellow". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ^ "Pigments through the ages: Cadmium yellow". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "Pigments through the ages: Chrome yellow". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "LBNL Pigment Database: (Y10) Nickel Antimony Titanium Yellow Rutile (iii)". Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. 14 February 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "gamboge (gum resin)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ "Gamboge". Sewanee: The University of the South. 16 July 2002. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ^ Field, George (1869). Salter, Thomas (ed.). Field's Chromatography or Treatise on Colours and Pigments as Used by Artists. London: Winsor and Newton. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs – pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Russo, Dreher & Mathre 2003, p. 6.

- ^ Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs – pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Ed. (1989)

- ^ Hanelt, Peter (11 May 2001). Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricultural and Horticultural Crops: (Except Ornamentals). Springer. ISBN 9783540410171. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Lewington, Anna (1990). "Recreation-Plants that entertain us". Plants for people. London: Natural History Museum Publications. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-565-01094-2.

- ^ Eastaugh, Nicholas; Walsh, Valentine; Chaplin, Tracey; Siddall, Ruth (2004). The Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-5749-5. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Food Standards Australia New Zealand. "Food Additives- Numerical List". Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers Archived 7 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine", Food Standards Agency website. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "Acid Yellow 23". ChemBlink, an online database of chemicals from around the world. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ CFR 74.1705, 21 CFR 201.20

- ^ Wood, Roger M. (2004). Analytical methods for food additives. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-85573-722-8.

- ^ a b Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, p. 33.

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (1956), "The Early History of Lead Pigments and Cosmetics in China", T'oung Pao, 2nd ser., vol. 44, Leiden: Brill, pp. 413–438, JSTOR 4527434.

- ^ Dupree, Scratch (30 January 2017), "Colors", Cha, Hong Kong

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ Hsieh, Tracy Tsuei-ju; et al. (November 2020), "Basic Color Categories in Mandarin Chinese Revealed by Cluster Analysis", Journal of Vision, vol. 20, Rockville: Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, p. 6, doi:10.1167/jov.20.12.6, PMC 7671860, PMID 33196769.

- ^ a b Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, p. 82.

- ^ Aisin-Gioro, Puyi (1989) [First published 1964]. From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi 我的前半生 [The First Half of My Life; From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi] (in Chinese). Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 978-7-119-00772-4. – original

- ^ Hewitt, Duncan (28 November 2000). "Chinese porn trader jailed for life". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Eva Heller (2000), Psychologie de la couleur – effets et symboliques, p. 73.

- ^ "Hair dye and wigs in Ancient Rome". 10 November 2011. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Kettunen, Harri; Helmke, Christophe (5 December 2005). Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs (Workshop Handbook 10th European Maya Conference). Leiden: Wayeb & Leiden University. p. 75. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ Adams, Sean; Morioka, Noreen; Stone, Terry Lee (2006). Color Design Workbook: A Real World Guide to Using Color in Graphic Design. Gloucester, Mass.: Rockport Publishers. pp. 86. ISBN 159253192X. OCLC 60393965.

- ^ Kumar, Rohit Vishal; Joshi, Radhika (October–December 2006). "Colour, Colour Everywhere: In Marketing Too". SCMS Journal of Indian Management. 3 (4): 40–46. ISSN 0973-3167. SSRN 969272.

- ^ Essay on Yellow by Michel Pastoureau, Liberation, 5 December 2008

- ^ a b Henri Arvon (1951). Le bouddhisme, pp. 61–64.

- ^ "The Buddhanet- buddhist studies- the monastic robe". Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs- pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 62.

- ^ Sikh Rehat Maryada: Section Three, Chapter IV, Article V, r. Archived 18 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nishan Sahib (Sikh Museum)". Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Magical Properties of Colors". Wicca Living. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Alice A. (1995). The Seven Rays of Life. New York: Lucis Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-85330-142-4.

- ^ Stevens, Samantha. The Seven Rays: a Universal Guide to the Archangels. City: Insomniac Press, 2004. ISBN 1-894663-49-7, p. 24.

- ^ Swami Panchadasi (1912). The Human Aura: Astral Colors and Thought Forms Des Plaines, Illinois: Yogi Publications Society, p. 33.

- ^ "History of the Main Taxi Groups". Taxi Register. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Frank W. Cyr, 95, 'Father of the Yellow School Bus'". Columbia University Record. 21 (1). 8 September 1995. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Review backs yellow school buses". BBC. 12 September 2008. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Maximizing Mining Safety" (PDF). Caterpillar Global Mining: 4.

- ^ Bej, Mark (16 April 1994). "Learning the ["typical" US] Aspects". Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ a b Flag and Etiquette Committee (12 June 2006). "Pratique". Flag Etiquette. United States Power Squadrons. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English dictionary, 6th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2.

- ^ Picturesque Expressions: A Thematic Dictionary, 1st Edition. © 1980 The Gale Group, Inc.

- ^ Chow, Kat. "If We Called Ourselves Yellow". NPR.

- ^ Keevak, Michael (2011). Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. United States: Princeton University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-691-14031-5.

- ^ "'Yellow fever' fetish: Why do so many white men want to date a Chinese woman?". July 2014.

References

- Doran, Sabine (2013). The Culture of Yellow, or, The Visual Politics of Late Modernity. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-8587-7.

- Travis, Tim (2020). The Victoria and Albert Museum Book of Colour in Design. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-48027-4.

- Ball, Philip (2001). Bright Earth, Art and the Invention of Colour. Hazan (French translation). ISBN 978-2-7541-0503-3.

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur – Effets et symboliques. Pyramyd (French translation). ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Keevak, Michael (2011). Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14031-5.

- Pastoureau, Michel (2005). Le petit livre des couleurs. Editions du Panama. ISBN 978-2-7578-0310-3.

- Gage, John (1993). Colour and Culture – Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. Thames and Hudson (Page numbers cited from French translation). ISBN 978-2-87811-295-5.

- Varichon, Anne (2000). Couleurs – pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02084697-4.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2012). Color in Art. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-0111-5.

- Russo, Ethan; Dreher, Melanie Creagan; Mathre, Mary Lynn, eds. (2003). Women and Cannabis: Medicine, Science, and Sociology (1st ed.). Psychology Press (published March 2003). ISBN 978-0-7890-2101-4. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Willard, Pat (2002). Secrets of Saffron: The Vagabond Life of the World's Most Seductive Spice. Beacon Press (published 11 April 2002). ISBN 978-0-8070-5009-5.

- Arvon, Henri (1951). Le bouddhisme. Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-055064-8.