Secure record linkage of large health data sets: Evaluation of a hybrid cloud model

Contents

Sudano-Sahelian architecture refers to a range of similar indigenous architectural styles common to the African peoples of the Sahel and Sudanian grassland (geographical) regions of West Africa, south of the Sahara, but north of the fertile forest regions of the coast.

This style is characterized by the use of mudbricks and adobe plaster, with large wooden-log support beams that jut out from the wall face for large buildings such as mosques or palaces. These beams also act as scaffolding for reworking, which is done at regular intervals, and involves the local community.

Historical background

Large Neolithic proto-urban walled stone settlements, likely built by Mande-speaking Soninke peoples date from around 1,600-400 BC at Dhar Tichitt and nearby sites in southeastern Mauritania.[2][3] Other early examples of Sudano-Sahelian style are probably from Dia around 600 BC[4] and Jenné-Jeno around 250 BC, both in Mali, where the first evidence of permanent mudbrick architecture in the region is found, including residences and a large city wall.[5] The first Great Mosque of Djenné (built around 1200 to 1330[6]) in modern Mali, according to traditional accounts, was constructed on the site of an older pre-Islamic palace by the city's king.[7]

Starting in the 9th century AD, Muslim merchants came to play a vital role in the western Sahel region through trans-Saharan trade networks.[8] The earliest mosques discovered in sub-Saharan Africa are at Kumbi Saleh (in present-day southern Mauritania), the former capital of the Ghana Empire.[9] Here, a mosque has been discovered which consisted of a courtyard, a prayer hall, and a square minaret, built in dry stone covered in red mud used as plaster. On both the exterior and interior of the mosque, this plaster was painted with floral, geometric, and epigraphic motifs. A similar stone mosque from the same period has been found at Awdaghust.[10] Both mosques are dated generally between the 9th and 14th centuries. The mosque of Kumbi Saleh appears to have gone through multiple construction phases from the 10th century to the early 14th century.[10] At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in domed-shaped dwellings in the king's section of the city, surrounded by a great enclosure. Traders lived in stone houses in a section which possessed 12 mosques (as described by Al-Bakri), one centered on Friday prayer.[11] The king is said to have owned several mansions, one of which was 66 feet long, 42 feet wide, contained seven rooms, was two stories high, and had a staircase; with the walls and chambers filled with sculpture and painting.[12]

A variety of possible influences on this architecture have been suggested. North African and Andalusi architecture to the north may have been one of these,[14] with the existence of square minarets possibly reflecting the influence of the Great Mosque of Kairouan.[8] As Islamization progressed across the region, more variations developed in mosque architecture, including the adoption of traditional local forms not previously associated with Islamic architecture.[15] Under Songhai influence, minarets took on a more pyramidal appearance and became stepped or tiered on three levels, as exemplified by the tower of the mosque–tomb of Askia al-Hajj Muhammad in Gao (present-day Mali). In Timbuktu, the Sankoré Mosque (established in the 14th-15th centuries[16] and rebuilt in the 16th century, with later additions[17]), had a tapering minaret and a prayer hall with rows of arches.[15] The presence of tapering minarets may also reflect cultural contacts with M'zab region to the north,[15] while decoration found at Timbuktu may reflect contacts with Berber communities in what is now Mauritania.[18] More local or indigenous pagan cultures may have also been an influence in the later Islamic architecture of the region.[14]

During the French colonial occupation of the Sahel, French engineers and architects had a role in popularizing a "Neo-Sudanese" style based on local traditional architecture but emphasizing symmetry and monumentality.[19][20][1] The Great Mosque of Djenné, which was previously established in the 14th century but demolished in the early 19th century,[20] was rebuilt in 1906–1907 under the direction of Ismaila Traoré and with guidance from French engineers.[1][19] Now the largest earthen (mud) building in sub-Saharan Africa, it served as a model for the new style and for other mosques in the region, including the Grand Mosque of Mopti built by the French administration in 1935.[1][19] Other 20th-century and more recent mosques in West Africa have tended to replicate a more generic style similar to that of modern Egypt.[20]

General

While the architecture of this region shares a certain style, a wide variety of materials and local styles are evident across this wide geographic range.[8][22] In the more arid western Sahara and northern Sahel regions, stone predominates as a building material and is often associated with Berber cultures. In the southern Sahel and savannah regions mudbrick and rammed earth are the main material and is now associated with the most monumental examples of West African Islamic architecture. In some places, like Timbuktu and Oualata, both building materials are used together, with stone constructions either covered or bound with a mud plaster.[23]

In the earthen architecture of the region, scholar Andrew Petersen distinguishes two general styles: a "western" style that may have its roots in Djenné (present-day Mali), and an "eastern" style associated with Hausa architecture that may have its roots in Kano (present-day Nigeria).[19] The eastern or Hausa style is generally more plain on the exterior of buildings, but is characterized by diverse interior decoration and the much greater use of wood.[19] Mosques often have prayer halls with pillars supporting flat or slightly domed roofs of wood and mud.[15][25] An exceptional example is the 19th-century Great Mosque of Zaria (present-day Nigeria), which has parabolic arches and a roof of shallow domes.[15][26] The western or "Sudan" style is characterized by more elaborate and decorated exterior façades whose compositions emphasize verticality. They have tapering buttresses with cone-shaped summits, mosques have a large tower over the mihrab, and wooden stakes (toron) are often embedded in the walls – used for scaffolding but possibly also for some symbolic purpose.[19]

Mud architecture building techniques

The traditional earth building construction technology has a particular name called “banco” in West Africa, meaning a wet-mud process similar with the concept of coil pottery. When banco technology continues to be the criterion for dwellings in the savannah area, an alternative method is to use earthen brick consequently with wet mud. The brick is cast into rectangular shape and dried in the sun.[27]

One symbol of the Sudanese architecture is the man-made, conical earthen pillars. Being combined with the building itself uniquely, they often project horizontally to the outside like engaged pillars. Being so omnipresent in the vernacular buildings, they can be found singularly or clustered at multiple entrances. As a hallmark of the Sudano Sahelian architecture, they mark the indication of continuity and productivity.

Variations

Substyles

The Sudano-Sahelian architectural style itself can be broken down into four smaller sub-styles that are typical of different ethnic groups in the region.[28] The examples used here illustrate the construction of mosques as well as palaces, as the architectural style is concentrated around inland Muslim populations. As with the people, many of these styles cross-pollinate and produce buildings with shared features. Any one of these styles is not exclusive to one particular modern countries borders, but are linked to the ethnicity of its builders or surrounding populations. For example, a Malian migrant community in traditionally Gur area may build in the style characteristic of their ancestral homeland, while neighbouring Gur buildings are built in the local style. These styles include:

- Malian – of the various Manden groups of southern and central Mali. Characterized by the Great Mosque of Djenné and the Kani-Kombole Mosque of Mali.

- Songhai – of the various Songhai groups of Niger and Northern Mali. Characterized by the Tomb of Askia in Gao, Djingareyber and the Zarmakoy Palace in Dosso

- Fortress style[29] – predominantly used by the Zarma-Songhai peoples of Niger and Mali, Hausa-Fulani, Tuareg and Arab mixed communities in Agadez, and the Kanuri people of Lake Chad. Military aspect to construction of high protective compound walls built around a central courtyard. Minaret is the only structure with support beams showing. Characterized by the Sankore Mosque of Timbuktu, the tomb of Askia in Gao Mali, and the Agadez mosque of northern Niger.

- Hausa[30] – The characteristic Hausa architectural style predominant in North and Northwestern Nigeria, Niger, Eastern Burkina Faso, Northern Benin, and Hausa-predominant zango districts and neighbourhoods throughout West Africa. Characterised by its attention of stucco detail in abstract design and extensive use of parapets. One to two storey buildings. Examples in the architecture of the Yamma Mosque and old town of Zinder, The Hausa quarter of Agadez Niger, the Gidan Rumfa of Kano, and various Hausa districts across West Africa.

- Volta basin – of the Gur and Manden groups of Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and northern Côte d'Ivoire. Often the most conservative of the various substyles. Typically features a single courtyard, characterized by high white and black painted walls, inward curved turrets supporting an exterior wall, and a larger turret nearer the center. Characterized by the Larabanga mosque of Ghana and the Bobo-Dioulasso Grand Mosque.

-

Agadez Grand Mosque, Niger (Fortress style)

-

An ancestral multi-storey townhouse, Agadez, Niger (Hausa/Tubali)

-

Larabanga Mosque, Ghana (Gur-Voltaic).

Difference between Savannah and Sahelian styles

The earthen architecture in the Sahel zone region is noticeably different from the building style in the neighboring savannah. The "old Sudanese" cultivators of the savannah built their compounds out of several cone-roofed houses. This was primarily an urban building style, associated with centres of trade and wealth, characterised by cubic buildings with terraced roofs comprise the typical style.

They lend a characteristic appearance to the close-built villages and cities. Large buildings such as mosques, representative residential and youth houses stand out in the distance. They are landmarks in a flat landscape that point to a complex society of farmers, craftsmen and merchants with a religious and political upper class.

With the expansion of Sahelian kingdoms south to the rural areas in the savannas (inhabited by culturally or ethnically similar groups to those in the Sahel), the Sudano-Sahelian style was reserved for mosques, palaces, the houses of nobility or townsfolk (as is evident in the Gur-Voltaic style), whereas among commonfolk, there was a mix between either typically distinct Sudano-Sahelian styles for wealthier families, and older African roundhut styles for rural villages and family compounds.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

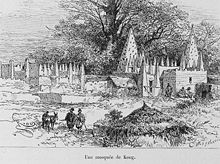

Historic mosque of Kong, now in Côte d'Ivoire, 1892 | |

| Location | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(iv) |

| Reference | 1648 |

| Inscription | 2021 (44th Session) |

| Area | 0.13 ha |

| Buffer zone | 2.33 ha |

Conservation

Several outstanding examples of religious and secular Sudano-Sahelian architecture have been awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status. The historic centers of Djenné, Mali and Agadez, Niger were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1988[31] and 2013,[32] respectively. In 2021, 8 small mosques in northern Côte d’Ivoire exemplifying a special type of Volta Basin religious architecture were also inscribed on the World Heritage list.[33] These mosques were probably originally constructed between the 17th and 19th centuries, as trade routes from the Empire of Mali spread to the south.[33]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Bloom & Blair 2009, Mali, Republic of

- ^ Holl, Augustin F.C. (2009). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". C. R. Geoscience. 241 (8): 703–712. Bibcode:2009CRGeo.341..703H. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.

- ^ Holl A (1985). "Background to the Ghana Empire: archaeological investigations on the transition to statehood in the Dhar Tichitt region (Mauritania)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 4 (2): 90–94. doi:10.1016/0278-4165(85)90005-4.

- ^ Arazi, Noemie. "Tracing History in Dia, in the Inland Niger Delta of Mali -Archaeology, Oral Traditions and Written Sources" (PDF). University College London. Institute of Archaeology.

- ^ Brass, Mike (1998), The Antiquity of Man: East & West African complex societies

- ^ Bourgeois 1987

- ^ "When the sultan became a Muslim. he had his palace pulled down and the site turned into a mosque dedicated to God Most High. This is the present congregational mosque. He built another palace for himself and his household near the mosque on the east side." Hunwick 1999, p. 18

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, Africa

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Africa

- ^ a b Pradines 2022, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Historical Society of Ghana. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, The Society, 1957, p. 81

- ^ Davidson, Basil. The Lost Cities of Africa. Boston: Little Brown, 1959, p. 86

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Timbuktu

- ^ a b Petersen 1996, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom & Blair 2009, Africa

- ^ Pradines 2022, p. 63.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Timbuktu

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 307.

- ^ a b c d e f Petersen 1996, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, Africa

- ^ Pradines 2022, pp. 37, 53–55.

- ^ Petersen 1996, pp. 306–308.

- ^ Petersen 1996, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Mali, Republic of

- ^ Pradines 2022, p. 84.

- ^ "Archnet > Site > Friday Mosque at Zaria". www.archnet.org. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ "Construction Technology and Architecture | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-01-15.

- ^ Team, Editorial (2021-03-30). "Vernacular Architecture: Tradition and Beauty in Regional Styles". RMJM. Retrieved 2023-01-15.

- ^ Kane, Ousmane (2015-04-01). "Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal". Cahiers d'études africaines (in French) (217). doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.18050. ISSN 0008-0055.

- ^ Umar, Gali Kabir; Yusuf, Danjuma Abdu; Ahmed, Abubakar; Usman, Abdullahi M. (2019-09-01). "The practice of Hausa traditional architecture: Towards conservation and restoration of spatial morphology and techniques". Scientific African. 5: e00142. Bibcode:2019SciAf...500142U. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00142. ISSN 2468-2276. S2CID 202901961.

- ^ "Old Towns of Djenné". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Agadez". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Sudanese style mosques in northern Côte d'Ivoire". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

Sources

- Bourgeois, Jean-Louis (1987), "The history of the great mosques of Djenné", African Arts, 20 (3), UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center: 54–92, doi:10.2307/3336477, JSTOR 3336477

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3.

- Pradines, Stéphane (2022). Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-47261-7.

Further reading

- Aradeon, Suzan B. (1989), "Al-Sahili: the historian's myth of architectural technology transfer from North Africa", Journal des Africanistes, 59: 99–131, doi:10.3406/jafr.1989.2279.

- Bourgeois, Jean-Louis; Pelos, Carollee (photographer); Davidson, Basil (historical essay) (1989), Spectacular vernacular : the adobe tradition, New York: Aperture Foundation, ISBN 0-89381-391-5. Second edition published in 1996.

- Prussin, Labelle (1986), Hatumere: Islamic design in West Africa, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-03004-4.

- Schutyser, S. (photographer); Dethier, J.; Gruner, D. (2003), Banco, Adobe Mosques of the Inner Niger Delta, Milan: 5 Continents Editions, ISBN 88-7439-051-3.