Secure record linkage of large health data sets: Evaluation of a hybrid cloud model

Contents

| Battle of Chaldiran (1514) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman–Persian Wars | |||||||||

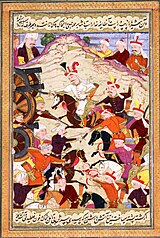

Artwork of the Battle of Chaldiran at the Chehel Sotoun Pavilion in Isfahan | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

60,000[9] Or 100,000[10][11] 100–150 cannon[12] Or 200 cannon and 100 mortars[7] |

40,000[13][11] Or 55,000[14] Or 80,000[10] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Heavy losses[15] Or less than 2,000[16][full citation needed] |

Heavy losses[15] Or approximately 5,000[17][full citation needed] | ||||||||

Location within Caucasus Mountains | |||||||||

The Battle of Chaldiran (Persian: جنگ چالدران; Turkish: Çaldıran Savaşı) took place on 23 August 1514 and ended with a decisive victory for the Ottoman Empire over the Safavid Empire. As a result, the Ottomans annexed Eastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia from Safavid Iran.[3][4] It marked the first Ottoman expansion into Eastern Anatolia, and the halt of the Safavid expansion to the west.[18] The Battle of Chaldiran was just the beginning of 41 years of destructive war, which only ended in 1555 with the Peace of Amasya. Though the Safavids eventually reconquered Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia under the reign of Abbas the Great (r. 1588–1629), they would be permanently ceded to the Ottomans by the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.

At Chaldiran, the Ottomans had a larger, better-equipped army numbering 60,000 to 100,000 and many heavy artillery pieces. In contrast, the Safavid army numbered 40,000 to 80,000 and did not have artillery. Ismail I, the leader of the Safavids, was wounded and almost captured during the battle. His wives were captured by the Ottoman leader Selim I,[19] with at least one married off to one of Selim's statesmen.[20] Ismail retired to his palace and withdrew from government administration[21] after this defeat and never again participated in a military campaign.[18] After their victory, Ottoman forces marched deeper into Persia, briefly occupying the Safavid capital, Tabriz, and thoroughly looting the Persian imperial treasury.[5][6]

The battle is one of major historical importance because it not only negated the idea that the murshid of the Qizilbash was infallible,[22] but also led Kurdish chiefs to assert their authority and switch their allegiance from the Safavids to the Ottomans.[23][24]

Background

After Selim I's successful struggle against his brothers for the throne of the Ottoman Empire, he was free to turn his attention to the internal unrest he believed was stirred up by the Qizilbash, a Twelver Shi'i warrior-dervish group who had sided with other members of the dynasty against him and had been semi-officially supported by Bayezid II. Selim now feared that they would incite the population against his rule in favor of their leader, who was now the Safavid emperor. His partisans believed he was descended from Muhammad and infallible. Selim secured a jurist opinion that described Isma'il and the Qizilbash as "unbelievers and heretics," enabling him to undertake extreme measures on his way eastward to pacify the country.[25]: 104 Selim accused Ismail of departing from the faith:[25]: 105

... you have subjected the upright community of Muhammad... to your devious will [and] undermined the firm foundation of the faith; you have unfurled the banner of oppression in the cause of aggression [and] no longer uphold the commandments and prohibitions of the Divine Law; you have incited your abominable Shii faction to unsanctified sexual union and the shedding of innocent blood.

Before Selim started his campaign, he ordered the execution of some 40,000 Qizilbash in Anatolia "as punishment for their rebellious behaviour."[11] He then also tried to block the import of Iranian silk into his realm, a measure which met "with some success".[11]

Selim sent the following letter to Ismail, which outlined both Selim's claim to the caliphate and Ismail's heresy:[26]

This missive which is stamped with the seal of victory and which is, like inspiration descending from the heavens, witness to the verse "We never chastise until We send forth a Messenger" [Quran XVII] has been graciously issued by our most glorious majesty-we who are the Caliph of God Most High in this world, far and wide; the proof of the verse "And what profits men abides in the earth" [Quran XIII] the Solomon of Splendor, the Alexander of eminence; haloed in victory, Faridun triumphant; slayer of the wicked and the infidel, guardian of the noble and the pious; the warrior in the Path, the defender of the Faith; the champion, the conqueror; the lion, son and grandson of the lion; standard-bearer of justice and righteousness, Sultan Selim Shah, son of Sultan Bayezid, son of Sultan Muhammad Khan–and is addressed to the ruler of the kingdom of the Persians, the possessor of the land of tyranny and perversion, the captain of the vicious, the chief of the malicious, the usurping Darius of the time, the malevolent Zahhak of the age, the peer of Cain, Prince Ismail.

When Selim started his march east, the Khanate of Bukhara invaded the Safavids in the east. This Uzbek state had been recently brought to prominence by Muhammad Shaybani, who had fallen in battle against Isma'il only a few years before. Attempting to avoid having to fight a war on two fronts, Isma'il employed a scorched earth policy against Selim in the west.[25]: 105

Selim's army was discontented by the difficulty in supplying the army in light of Isma'il's scorched earth campaign, the extremely rough terrain of the Armenian highlands, and that they were marching against Muslims. The janissaries even fired their muskets at the Sultan's tent in protest at one point. When Selim learned of the Safavid army forming at Chaldiran, he quickly moved to engage Isma'il, partly to stifle his army's discontent.[25]: 106

Battle

The Ottomans deployed heavy artillery and thousands of Janissaries equipped with gunpowder weapons behind a barrier of carts. The Safavids, who did not have artillery at their disposal at Chaldiran,[27] used cavalry to engage the Ottoman forces. The Safavids attacked the Ottoman wings to avoid the Ottoman artillery positioned at the center. However, the Ottoman artillery was highly maneuverable and the Safavids suffered disastrous losses.[28] The advanced Ottoman weaponry (cannons and muskets wielded by janissaries) was the deciding factor of the battle as the Safavid forces, who only had traditional weaponry, were decimated. Unlike the Ottomans, the Safavids also suffered from poor planning and ill-disciplined troops.[29]

Aftermath

Following their victory, the Ottomans captured the Safavid capital city of Tabriz on 7 September,[18] which they first pillaged and then evacuated. That week's Friday sermon in mosques throughout the city was delivered in Selim's name.[30] Selim was however unable to press on after Tabriz due to the discontent amongst the janissaries.[18] The Ottoman Empire successfully annexed Eastern Anatolia (encompassing Western Armenia) and Upper Mesopotamia from the Safavids. These areas changed hands several times over the following decades; however, the Ottoman hold would not be set until the 1555 Peace of Amasya following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555). Effective governmental rule and eyalets would not be established over these regions until the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.[citation needed]

After two of his wives and entire harem were captured by Selim[31][18] Ismail was heartbroken and resorted to drinking alcohol.[32] His aura of invincibility shattered,[33] Ismail ceased participating in government and military affairs,[34] due to what seems to have been the collapse of his confidence.[18]

Selim married one of Ismail's wives to an Ottoman judge. In contrast to their previous exchanges, Ismail sent four envoys, gifts, and, in contrast to their previous exchanges, words of praise to Selim to help retrieve her. Instead of giving his wife back, Selim cut the messengers' noses off and sent them back empty-handed.[30]

After the defeat at Chaldiran, however, the Safavids made drastic domestic changes. From then on, firearms were made an integral part of the Persian armies, and Ismail's son, Tahmasp I, deployed cannons in subsequent battles.[35][36]

During the retreat of the Ottoman troops, they were intensively harassed by Georgian light cavalry of the Safavid army, deep into the Ottoman realm.[37]

The Mamluk Sultanate refused to send messengers to congratulate Selim after the battle and prohibited celebrating the Ottoman military victory. In contrast, the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople led to days of festivities in the Mamluk capital, Cairo.[30]

After the victorious battle of Chaldiran, Selim I next threw his forces southward in the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–1517).[38]

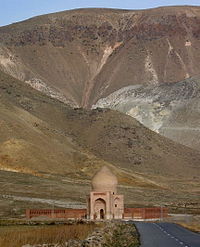

Battlefield

The site of the battle is near Gal Ashaqi, a village around 6 km west of the town of Siah Cheshmeh, south of Maku, north of Qarah Zia ol Din. A large brick dome was built at the battlefield site in 2003 along with a statue of Seyid Sadraddin, one of the main Safavid commanders.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Mustafa Çetin Varlık (1988–2016). "Çaldiran Savasi Yavuz Sultan Selim ile Safevî Hükümdarı Şah İsmâil arasında Çaldıran ovasında 23 Ağustos 1514'te yapılan meydan savaşı". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 483. ISBN 978-1851096725.

- ^ a b David Eggenberger, An Encyclopedia of Battles, (Dover Publications, 1985), 85.

- ^ a b Ira M. Lapidus. "A History of Islamic Societies" Archived 2023-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139991507. p. 336.

- ^ a b Matthee, Rudi (2008). "Safavid Dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

Following Čālderān, the Ottomans briefly occupied Tabriz.

- ^ a b Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ a b Savory 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Sebastian, Peter (1988). Turkish prosopography in the Diarii of Marino Sanuto, 1496–1517. University of London. p. 61.

- ^ Keegan & Wheatcroft, Who's Who in Military History, Routledge, 1996. p. 268 "In 1515 Selim marched east with some 60,000 men; a proportion of these were skilled Janissaries, certainly the best infantry in Asia, and the sipahis, equally well-trained and disciplined cavalry. [...] The Persian army, under Shah Ismail, was almost entirely composed of Turcoman tribal levies, a courageous but ill-disciplined cavalry army. Slightly inferior in numbers to the Turks, their charges broke against the Janissaries, who had taken up fixed positions behind rudimentary field works."

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, ed. Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters, p. 286, 2009

- ^ a b c d McCaffrey 1990, pp. 656–658.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2014). "Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450–1800". Journal of World History. 25: 110. doi:10.1353/jwh.2014.0005. S2CID 143042353.

- ^ Roger M. Savory, Iran under the Safavids, Cambridge, 1980, p. 41

- ^ Keegan & Wheatcroft, Who's Who in Military History, Routledge, 1996. p. 268

- ^ a b Kenneth Chase, Firearms: A Global History to 1700, 120.

- ^ Serefname II

- ^ Serefname II s. 158

- ^ a b c d e f Mikaberidze 2015, p. 242.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, 224;"The magnitude of the disaster may be judged from the fact that the royal harem with two of Ismai'il's wives fell into the hands of the enemy."

- ^ Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, (Oxford University Press, 1993), 37.

- ^ Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shiʻi Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, (Yale University Press, 1985), 107.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, 359.

- ^ Martin Sicker, The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab conquests to the Siege of Vienna, (Praeger Publishers, 2000), 197.

- ^ Aktürk, Ahmet Serdar (2018). "Family, Empire, and Nation: Kurdish Bedirkhanis and the Politics of Origins in a Changing Era". Journal of Global South Studies. 35 (2): 393. doi:10.1353/gss.2018.0032. ISSN 2476-1419. S2CID 158487762. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Finkel, Caroline (2012). Osman's Dream. John Murray Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-84854-785-8.; Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Caroline Finkel. Hachette UK

- ^ Karen M. Kern (2011). Imperial Citizen: Marriage and Citizenship in the Ottoman Frontier Provinces of Iraq. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Floor 2001, p. 189.

- ^ Andrew James McGregor, A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War, (Greenwood Publishing, 2006), 17.

- ^ Gene Ralph Garthwaite, The Persians, (Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 164.

- ^ a b c Mikhail, Alan (2020). God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World. Liveright. ISBN 978-1631492396.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, p. 224.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Islam, Part 1, ed. Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, p. 401

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, Part 1, By Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, p. 401.

- ^ Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran (ABC-CLIO, 2012) 86

- ^ Gunpowder and Firearms in the Mamluk Sultanate Reconsidered, Robert Irwin, The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian politics and society, ed. Michael Winter and Amalia Levanoni, (Brill, 2004) 127

- ^ Matthee, Rudolph (Rudi). "Safavid Persia:The History and Politics of an Islamic Empire". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Floor 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya (2018). The Ottoman Empire: A Short History. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 9781558764491. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2016 – via Google Books.

Sources

- Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587–1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles, ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

- Floor, Willem (2001). Safavid Government Institutions. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591353.

- McCaffrey, Michael J. (1990). "Čālderān". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 6. pp. 656–658.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Savory, Roger (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521042512.

Further reading

- Floor, Willem (2020). "The Earliest Account of the Battle of Chaldiran?". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 170 (2): 371–395. doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.170.2.0371. S2CID 226585270.

- Moreen, Vera B. (2019). "Echoes of the Battle of Čālderān: The Account of the Jewish Chronicler Elijah Capsali (c. 1490 – c. 1555)". Studia Iranica. 48 (2): 195–234. doi:10.2143/SI.48.2.3288439.

- Palazzo, Chiara (2016). "The Venetian News Network in the Early Sixteenth Century: The Battle of Chaldiran". In Raymond, Joad; Moxham, Noah (eds.). News Networks in Early Modern Europe. Brill. pp. 849–869. doi:10.1163/9789004277199_038. ISBN 9789004277175.

- Rahimlu, Yusof; Esots, Janis (2021). "Chāldirān (Çaldıran)". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

- Walsh, J.R. (1965). "Čāldirān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Wood, Barry (2017). "The Battle of Chālderān: Official History and Popular Memory". Iranian Studies. 50 (1): 79–105. doi:10.1080/00210862.2016.1159504. S2CID 163512376.

- Wood, Barry (2022). "Chāldirān, Battle of". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.