Risk assessment of over-the-counter cannabinoid-based cosmetics: Legal and regulatory issues governing the safety of cannabinoid-based cosmetics in the UAE

Contents

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gamanil, Lomont, Tymelyt, others |

| Other names | Lopramine; DB-2182; Leo-460; WHR-2908A[1][2][3][4] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 7%[5] |

| Protein binding | 99%[6] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (via cytochrome P450, including CYP2D6)[7] |

| Metabolites | Desipramine (major) |

| Elimination half-life | Up to 5 hours;[1] 12–24 hours (active metabolites) |

| Excretion | Urine, feces (mostly as metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.254 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

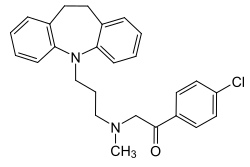

| Formula | C26H27ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 418.97 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Lofepramine, sold under the brand names Gamanil, Lomont, and Tymelyt among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) which is used to treat depression.[7][3][8] The TCAs are so named as they share the common property of having three rings in their chemical structure. Like most TCAs lofepramine is believed to work in relieving depression by increasing concentrations of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin in the synapse, by inhibiting their reuptake.[7] It is usually considered a third-generation TCA, as unlike the first- and second-generation TCAs it is relatively safe in overdose and has milder and less frequent side effects.[9]

Lofepramine is not available in the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, although it is available in Ireland, Japan, South Africa and the United Kingdom, among other countries.[1]

Depression

In the United Kingdom, lofepramine is licensed for the treatment of depression which is its primary use in medicine.[6][10]

Lofepramine is an efficacious antidepressant with about 64% patients responding to it.[11]

Contraindications

To be used with caution, or not at all, for people with the following conditions:[7]

- Heart disease

- Impaired kidney or liver function

- Narrow angle glaucoma

- In the immediate recovery period after myocardial infarction

- In arrhythmias (particularly heart block)

- Mania

- In severe liver and/or severe renal impairment[12]

And in those being treated with amiodarone or terfenadine.[7]

Pregnancy and lactation

Lofepramine use during pregnancy is advised against unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.[7] This is because its safety during pregnancy has not been established and animal studies have shown some potential for harm if used during pregnancy.[7] If used during the third trimester of pregnancy it can cause insufficient breathing to meet oxygen requirements, agitation and withdrawal symptoms in the infant.[7] Likewise its use by breastfeeding women is advised against, except when the benefits clearly outweigh the risks, due to the fact it is excreted in the breast milk and may therefore adversely affect the infant.[7] Although the amount secreted in breast milk is likely too small to be harmful.[13]

Side effects

The most common adverse effects (occurring in at least 1% of those taking the drug) include agitation, anxiety, confusion, dizziness, irritability, abnormal sensations, like pins and needles, without a physical cause, sleep disturbances (e.g. sleeplessness) and a drop in blood pressure upon standing up.[13] Less frequent side effects include movement disorders (like tremors), precipitation of angle closure glaucoma and the potentially fatal side effects paralytic ileus and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[13]

Dropout incidence due to side effects is about 20%.[11]

Side effects with unknown frequency include (but are not limited to):[13]

- Digestive effects:

- Constipation

- Diarrhoea

- Dry mouth

- Nausea

- Taste disturbances

- Vomiting

- Effects on the heart:

- Blood abnormalities:

- Abnormal blood cell counts

- Blood sugar changes

- Low blood sodium levels

- Breast effects:

- Breast enlargement, including in males.

- Spontaneous breast milk secretion that is unrelated to breastfeeding or pregnancy

- Effects on the skin:

- Abnormal sweating

- Hair loss

- Hives

- Increased light sensitivity

- Itching

- Rash

- Mental / neurologic effects:

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Headache

- Hypomania/mania

- Seizures

- Suicidal behaviour

- Other effects:

- Appetite changes

- Blurred vision

- Difficulty emptying the bladder

- Difficulty talking due to difficulties in moving the required muscles

- Liver problems

- Ringing in the ears

- Sexual dysfunction, such as impotence

- Swelling

- Weight changes

Withdrawal

If abruptly stopped after regular use it can cause withdrawal effects such as sleeplessness, irritability and excessive sweating.[7]

Overdose

Compared to other TCAs, lofepramine is considered to be less toxic in overdose.[13] Its treatment is mostly a matter of trying to reduce absorption of the drug, if possible, using gastric lavage and monitoring for adverse effects on the heart.[7]

Interactions

Lofepramine is known to interact with:[13][7]

- Alcohol. Increased sedative effect.

- Altretamine. Risk of severe drop in blood pressure upon standing.

- Analgesics (painkillers). Increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias.

- Anticoagulants (blood thinners). Lofepramine may inhibit the metabolism of certain anticoagulants leading to a potentially increased risk of bleeding.

- Anticonvulsants. Possibly reduce the anticonvulsant effect of antiepileptics by lowering the seizure threshold.

- Antihistamines. Possible increase of antimuscarinic (potentially increasing risk of paralytic ileus, among other effects) and sedative effects.

- Antimuscarinics. Possible increase of antimuscarinic side-effects.

- Anxiolytics and hypnotics. Increased sedative effect.

- Apraclonidine. Avoidance advised by manufacturer of apraclonidine.

- Brimonidine. Avoidance advised by manufacturer of brimonidine.

- Clonidine. Lofepramine may reduce the antihypertensive effects of clonidine.

- Diazoxide. Enhanced hypotensive (blood pressure-lowering) effect.

- Digoxin. May increase risk of irregular heart rate.

- Disulfiram. May require a reduction of lofepramine dose.

- Diuretics. Increased risk of reduced blood pressure on standing.

- Cimetidine, diltiazem, verapamil. May increase concentration of lofepramine in the blood plasma.

- Hydralazine. Enhanced hypotensive effect.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Advised not to be started until at least 2 weeks after stopping MAOIs. MAOIs are advised not to be started until at least 1–2 weeks after stopping TCAs like lofepramine.

- Moclobemide. Moclobemide is advised not to be started until at least one week after treatment with TCAs is discontinued.

- Nitrates. Could possibly reduce the effects of sublingual tablets of nitrates (failure to dissolve under tongue owing to dry mouth).

- Rifampicin. May accelerate lofepramine metabolism thereby decreasing plasma concentrations of lofepramine.

- Ritonavir. May increase lofepramine concentration in the blood plasma.

- Sodium nitroprusside. Enhanced hypotensive effect.

- Thyroid hormones. Effects on the heart of lofepramine may be exacerbated.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | LPA | DSI | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 70 | 17.6–163 | Human | [16][17] |

| NET | 5.4 | 0.63–3.5 | Human | [16][17] |

| DAT | >10,000 | 3,190 | Human | [16] |

| 5-HT1A | 4,600 | ≥6,400 | Human | [18][19] |

| 5-HT2A | 200 | 115–350 | Human | [18][19] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | 244–748 | Rat | [20][21] |

| 5-HT3 | ND | 4,402 | Mouse | [21] |

| 5-HT7 | ND | >1,000 | Rat | [22] |

| α1 | 100 | 23–130 | Human | [18][23][17] |

| α2 | 2,700 | ≥1,379 | Human | [18][23][17] |

| β | >10,000 | ≥1,700 | Rat | [24][25] |

| D1 | 500 | 5,460 | Human/rat | [26] |

| D2 | 2,000 | 3,400 | Human | [18][23] |

| H1 | 245–360 | 60–110 | Human | [27] |

| H2 | 4,270 | 1,550 | Human | [27] |

| H3 | 79,400 | >100,000 | Human | [27] |

| H4 | 36,300 | 9,550 | Human | [27] |

| mACh | 67 | 66–198 | Human | [18][23] |

| M1 | 67 | 110 | Human | [28] |

| M2 | 330 | 540 | Human | [28] |

| M3 | 130 | 210 | Human | [28] |

| M4 | 340 | 160 | Human | [28] |

| M5 | 460 | 143 | Human | [28] |

| σ1 | 2,520 | 4,000 | Rodent | [29][14] |

| σ2 | ND | 1,611 | Rat | [14] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | ||||

Lofepramine is a strong inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and a moderate inhibitor of serotonin reuptake.[14] It is a weak-intermediate level antagonist of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.[14]

Lofepramine has been said to be a prodrug of desipramine,[30] although there is also evidence against this notion.[8]

Pharmacokinetics

Lofepramine is extensively metabolized, via cleavage of the p-chlorophenacyl group, to the TCA, desipramine, in humans.[7][8][1] However, it is unlikely this property plays a substantial role in its overall effects as lofepramine exhibits lower toxicity and anticholinergic side effects relative to desipramine while retaining equivalent antidepressant efficacy.[8] The p-chlorophenacyl group is metabolized to p-chlorobenzoic acid which is then conjugated with glycine and excreted in the urine.[7] The desipramine metabolite is partly secreted in the faeces.[7] Other routes of metabolism include hydroxylation, glucuronidation, N-dealkylation and N-oxidation.[7][1]

Chemistry

Lofepramine is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzazepine, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[31] Other dibenzazepine TCAs include imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, and trimipramine.[31][32] Lofepramine is a tertiary amine TCA, with its side chain-demethylated metabolite desipramine being a secondary amine.[33][30] Unlike other tertiary amine TCAs, lofepramine has a bulky 4-chlorobenzoylmethyl substituent on its amine instead of a methyl group.[32] Although lofepramine is technically a tertiary amine, it acts in large part as a prodrug of desipramine, and is more similar to secondary amine TCAs in its effects.[34] Other secondary amine TCAs besides desipramine include nortriptyline and protriptyline.[35][34] The chemical name of lofepramine is N-(4-chlorobenzoylmethyl)-3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C26H27ClN2O with a molecular weight of 418.958 g/mol.[2] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the free base form is not used.[2][3] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 23047-25-8 and of the hydrochloride is 26786-32-3.[2][3]

History

Lofepramine was developed by Leo Läkemedel AB.[36] It first appeared in the literature in 1969 and was patented in 1970.[36] The drug was first introduced for the treatment of depression in either 1980 or 1983.[36][37]

Society and culture

Generic names

Lofepramine is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while lofepramine hydrochloride is its USAN, BANM, and JAN.[2][3][38][4] Its generic name in French and its DCF are lofépramine, in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are lofepramina, in German is lofepramin, and in Latin is lofepraminum.[3][4]

Brand names

Brand names of lofepramine include Amplit, Deftan, Deprimil, Emdalen, Gamanil, Gamonil, Lomont, Tymelet, and Tymelyt.[1][2][3][4]

Availability

In the United Kingdom, lofepramine is marketed (as the hydrochloride salt) in the form of 70 mg tablets [12] and 70 mg/5 mL oral suspension.[39]

Research

Fatigue

A formulation containing lofepramine and the amino acid phenylalanine is under investigation as a treatment for fatigue as of 2015.[40]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Lofepramine Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. The Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 738–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 614–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ a b c d "Lofepramine". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- ^ Lancaster SG, Gonzalez JP (February 1989). "Lofepramine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness". Drugs. 37 (2): 123–140. doi:10.2165/00003495-198937020-00003. PMID 2649353. S2CID 195693275.

- ^ a b "Lofepramine 70mg tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Merck Serono. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Lofepramine 70 mg Film-coated Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). Datapharm. April 2016. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Leonard BE (October 1987). "A comparison of the pharmacological properties of the novel tricyclic antidepressant lofepramine with its major metabolite, desipramine: a review". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2 (4): 281–297. doi:10.1097/00004850-198710000-00001. PMID 2891742.

- ^ "SAFC Commercial Life Science Products & Services | Sigma-Aldrich". Safcglobal.com. 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ a b Kerihuel JC, Dreyfus JF (1991). "Meta-analyses of the efficacy and tolerability of the tricyclic antidepressant lofepramine". The Journal of International Medical Research. 19 (3). SAGE Publications: 183–201. doi:10.1177/030006059101900304. PMID 1834491. S2CID 22873432.

- ^ a b "Lofepramine 70mg Tablets". Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Joint Formulary Committee (2017). BNF 73 (British National Formulary) March 2017. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-0-85711-276-7.

- ^ a b c d e Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–258. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ a b c d Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (December 1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 283 (3): 1305–1322. PMID 9400006.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–565. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- ^ a b Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (December 1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology. 132 (2–3): 115–121. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ^ Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (August 1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–240. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023. S2CID 24889381.

- ^ a b Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, et al. (March 1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Research Monograph. 178: 440–466. PMID 9686407.

- ^ Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (August 1993). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (24): 18200–18204. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46830-X. PMID 8394362.

- ^ a b c d e Richelson E, Nelson A (July 1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 230 (1): 94–102. PMID 6086881.

- ^ Muth EA, Haskins JT, Moyer JA, Husbands GE, Nielsen ST, Sigg EB (December 1986). "Antidepressant biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45,030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative". Biochemical Pharmacology. 35 (24): 4493–4497. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90769-0. PMID 3790168.

- ^ Sánchez C, Hyttel J (August 1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 19 (4): 467–489. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMID 10379421. S2CID 19490821.

- ^ Deupree JD, Montgomery MD, Bylund DB (December 2007). "Pharmacological properties of the active metabolites of the antidepressants desipramine and citalopram". European Journal of Pharmacology. 576 (1–3): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.017. PMC 2231336. PMID 17850785.

- ^ a b c d Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (February 2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 385 (2): 145–170. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- ^ a b c d e Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (June 1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochemical Pharmacology. 45 (11): 2352–2354. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- ^ Weber E, Sonders M, Quarum M, McLean S, Pou S, Keana JF (November 1986). "1,3-Di(2-[5-3H]tolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (22): 8784–8788. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8784W. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMC 387016. PMID 2877462.

- ^ a b Anzenbacher P, Zanger UM (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6.

- ^ a b Ritsner MS (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6.

- ^ a b Lemke TL, Williams DA (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 580, 607. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ Cutler NR, Sramek JJ, Narang PK (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3.

- ^ a b Cowen P, Harrison P, Burns T (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3.

- ^ Anthony PK (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9.

- ^ a b c Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (July 2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chemical Communications (25): 3677–3692. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ^ Dart RC (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ "Lofepramine Rosemont 70mg/5ml Oral Suspension - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". 26 January 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Lofepramine/phenylalanine - MultiCell Technologies". AdisInsight. Springer International Publishing AG. Retrieved 3 August 2017.