Practical Applications of a SDMS (Scientific Data Management System)

Manila

Maynila (Filipino) | |

|---|---|

| City of Manila | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): Manila, God First Welcome Po Kayo sa Maynila (transl. You are welcome in Manila) | |

| Anthem: "Awit ng Maynila" (Song of Manila) | |

![Map of Metro Manila with Manila highlighted[a]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Manila_in_Metro_Manila.svg/250px-Manila_in_Metro_Manila.svg.png) Map of Metro Manila with Manila highlighted[a] | |

Location within the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 14°35′45″N 120°58′38″E / 14.5958°N 120.9772°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | National Capital Region |

| Legislative district | 1st to 6th district |

| Administrative district | 16 city districts |

| Established | 13th century or earlier |

| Sultanate of Brunei (Maynila) | 1500s |

| Spanish Manila | June 24, 1571 |

| City charter | July 31, 1901 |

| Highly urbanized city | December 22, 1979 |

| Barangays | 897 (see Barangays and districts) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlungsod |

| • Mayor | Maria Sheilah H. Lacuna-Pangan |

| • Vice Mayor | John Marvin C. Nieto |

| • Representatives | |

| • City Council | List |

| • Electorate | 1,133,042 voters (2022) |

| Area | |

| • City | 42.34 km2 (16.35 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,873 km2 (723 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 619.57 km2 (239.22 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 9.0 m (29.5 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 108 m (354 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 1,846,513 |

| • Density | 43,611.5/km2 (112,953/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 13,484,482 |

| • Urban density | 21,764.3/km2 (56,369/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 24,922,000 |

| • Metro density | 13,305.9/km2 (34,462/sq mi) |

| • Households | 486,293 |

| Demonym(s) | English: Manileño, Manilan; Spanish: manilense,[7] manileño (f. -a) Filipino: Manileño (f. -a), Manilenyo (f. -a), Taga-Maynila |

| Economy | |

| • Income class | special city income class |

| • Poverty incidence | 1.10 |

| • HDI | |

| • Revenue | ₱ 19,692 million (2022) |

| • Assets | ₱ 73,694 million (2022) |

| • Expenditure | ₱ 16,047 million (2022) |

| • Liabilities | ₱ 26,765 million (2022) |

| Utilities | |

| • Electricity | Manila Electric Company (Meralco) |

| • Water | • Maynilad (Majority) • Manila Water (Santa Ana and San Andres) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | +900 – 1-096 |

| PSGC | |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)2 |

| Native languages | Tagalog |

| Currency | Philippine peso (₱) |

| Website | manila |

| |

Manila (/məˈnɪlə/ mə-NIL-ə; Filipino: Maynila), officially the City of Manila (Filipino: Lungsod ng Maynila), is the capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines, after Quezon City. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on the island of Luzon, it is classified as a highly urbanized city. Manila is the world's most densely populated city proper,[5][6] with 43,611.5 inhabitants per square kilometer (112,953/sq mi) and a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020;[5] it is also the historic core of a built-up area that extends well beyond its administrative limits. Manila was the first chartered city in the country, designated by Philippine Commission Act No. 183 on July 31, 1901. It became autonomous with the passage of Republic Act No. 409, "The Revised Charter of the City of Manila", on June 18, 1949.[10][11] Manila is considered to be part of the world's original set of global cities because its commercial networks were the first to extend across the Pacific Ocean and connect Asia with the Spanish Americas through the galleon trade. This marked the first time an uninterrupted chain of trade routes circling the planet had been established.[12][13]

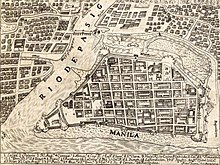

By 1258, a Tagalog-fortified polity called Maynila existed on the site of modern Manila. On June 24, 1571, after the defeat of the polity's last indigenous ruler, Rajah Sulayman, in the Battle of Bangkusay, Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi began constructing the walled fortification of Intramuros on the ruins of an older settlement from whose name the Spanish and English name Manila derives. Manila was used as the capital of the captaincy general of the Spanish East Indies, which included the Marianas, Guam, and other islands, and was controlled and administered for the Spanish crown by Mexico City in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

In modern times, the name "Manila" is commonly used to refer to the entire metropolitan area, the greater metropolitan area, and the city proper. Metro Manila, the officially defined metropolitan area, is the capital region of the Philippines, and includes the much larger Quezon City and the Makati Central Business District. It is the most populous region in the country, one of the most populous urban areas in the world,[14] and one of the wealthiest regions in Southeast Asia.

The Pasig River flows through the middle of Manila, dividing it into northern and southern sections. The city comprises 16 administrative districts and is divided into six political districts for the purposes of representation in the Congress of the Philippines and the election of city council members. In 2018, the Globalization and World Cities Research Network listed Manila as an "Alpha-" global city,[15] and ranked it seventh in economic performance globally and second regionally,[16] while the Global Financial Centres Index ranks Manila 79th in the world.[17] Manila is also the world's second most natural disaster-exposed city,[18] yet is also among the fastest-developing cities in Southeast Asia.[19]

Etymology

Maynilà, the Filipino name for the city, comes from the phrase may-nilà, meaning "where indigo is found".[20] Nilà is derived from the Sanskrit word nīla (नील), which refers to indigo dye and, by extension, to several plant species from which this natural dye can be extracted.[20][21] The name Maynilà was probably bestowed because of the indigo-yielding plants that grew in the area surrounding the settlement rather than because it was known as a settlement that traded in indigo dye.[20] Indigo dye extraction only became an important economic activity in the area in the 18th century, several hundred years after Maynila settlement was founded and named.[20] Maynilà eventually underwent a process of Hispanicization and adopted the Spanish name Manila.[22]

May-nilad

According to an antiquated, inaccurate, and now debunked etymological theory, the city's name originated from the word may-nilad (meaning "where nilad is found").[20] There are two versions of this false etymology. One popular incorrect notion is that the old word nilad refers to the water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) that grows on the banks of the Pasig River.[20] This plant species, however, was only recently introduced into the Philippines from South America and therefore could not be the source of the toponym for old Manila.[20]

Another incorrect etymology arose from the observation that, in Tagalog, nilád or nilár refers to a shrub-like tree (Scyphiphora hydrophyllacea; formerly Ixora manila Blanco) that grows in or near mangrove swamps.[20][23][24] Linguistic analysis, however, shows the word Maynilà is unlikely to have developed from this term. It is unlikely native Tagalog speakers would completely drop the final consonant /d/ in nilad to arrive at the present form Maynilà.[20] As an example, nearby Bacoor retains the final consonant of the old Tagalog word bakoód ("elevated piece of land"), even in old Spanish renderings of the placename (e.g., Vacol, Bacor).[25] Historians Ambeth Ocampo[26][27] and Joseph Baumgartner[20] have shown, in every early document, that the place name Maynilà was always written without a final /d/. This documentation shows that the may-nilad etymology is spurious.

Originally, the mistaken identification of nilad as the source of the toponym probably originated in an 1887 essay by Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, in which he mistakenly used the word nila to refer both to Indigofera tinctoria (true indigo) and to Ixora manila, which is actually nilád in Tagalog.[24]).[21][20] Early 20th century writings, such as those of Julio Nakpil,[28] and Blair and Robertson, repeated the claim.[29][27] Today, this erroneous etymology continues to be perpetuated through casual repetition in literature[30][31] and in popular use. Examples of popular adoption of this mistaken etymology include the name of a local utility company Maynilad Water Services and the name of an underpass close to Manila City Hall, Lagusnilad (meaning "Nilad Pass").[26]

On the other hand, in a rather first account of importance on the Philippine flora that appeared in 1704 as an Appendix to Ray's Historia Plantarum which is the Herbarium aliarumque Stirpium in Insula Luzone Philippinarum primaria nascentium... by Fr. Georg Josef Kamel[32], he mentioned that, Nilad arbor mediocris, rarissimi recta, ligno folido, et compacto ut Molavin, ubi abundant Mangle, locum vocant Manglar, ita ubi nilad, Maynilad, unde corrupte Manila (Nilad is an average tree, very rare straight, leafy wood, and compact like Molavin, where Mangle abounds, the place is called Manglar, so where nilad (abounds), Maynilad, whence the corruption Manila)[33], making this an earlier account of the change in this name.

History

Early history

| Battles of Manila |

|---|

| See also |

|

| Around Manila |

|

The earliest evidence of human life around present-day Manila is the nearby Angono Petroglyphs, which are dated to around 3000 BC. Negritos, the aboriginal inhabitants of the Philippines, lived across the island of Luzon, where Manila is located, before Malayo-Polynesians arrived and assimilated them.[34]

Manila was an active trade partner with the Song and Yuan dynasties of China.[35]

The polity of Tondo flourished during the latter half of the Ming dynasty as a result of direct trade relations with China. Tondo district was the traditional capital of the empire and its rulers were sovereign kings rather than chieftains. Tondo was named using traditional Chinese characters in the Hokkien reading, Chinese: 東都; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tong-to͘; lit. 'Eastern Capital', due to its chief position southeast of China. The kings of Tondo were addressed as panginoón in Tagalog ("lords"); anák banwa ("son of heaven"); or lakandula ("lord of the palace"). The Emperor of China considered the lakans—the rulers of ancient Manila—"王" (kings).[36]

During the 12th century, then-Hindu Brunei called "Pon-i", as reported in the Chinese annals Nanhai zhi, invaded Malilu 麻裏蘆 (present-day Manila) as it also administered Sarawak and Sabah, as well as the Philippine kingdoms of: Butuan, Sulu, Ma-i (Mindoro), Shahuchong 沙胡重 (present-day Zamboanga), Yachen 啞陳 (Oton), and 文杜陵 Wenduling (present-day Mindanao). Manila regained independence.[37] In the 13th century, Manila consisted of a fortified settlement and trading quarter on the shore of the Pasig River. It was then conquered by the Indianized empire of Majapahit, according to the epic eulogy poem Nagarakretagama, which described the area's conquest by Maharaja Hayam Wuruk. Selurong (षेलुरोङ्), a historical name for Manila, is listed in Canto 14 alongside Sulot – which is now Sulu – and Kalka. Selurong, together with Sulot, was able to regain independence afterward, and Sulu attacked and looted the then-Majapahit-invaded province Po-ni (Brunei) in retribution.[38]

During the reign of the Arab emir, Sultan Bolkiah – Sharif Ali's descendant – from 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei which had seceded from Hindu Majapahit and converted to Islam, had invaded the area. The Bruneians wanted to take advantage of Tondo's strategic position in direct trade with China and subsequently attacked the region and established the rajahnate of Maynilà (كوتا سلودوڠ; Kota Seludong). The rajahnate was ruled under Brunei and gave yearly tribute as a satellite state.[39] It created a new dynasty under the local leader, who accepted Islam and became Rajah Salalila or Sulaiman I. He established a trading challenge to the already rich House of Lakan Dula in Tondo. Islam was further strengthened by the arrival of Muslim traders from the Middle East and Southeast Asia.[40]

Spanish era

On June 24, 1571, conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in Manila and declared it a territory of New Spain (Mexico), establishing a city council in what is now Intramuros district. Inspired by the Reconquista, a war in mainland Spain to re-Christianize and reclaim parts of the country that had been ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate, he took advantage of a territorial conflict between Hindu Tondo and Islamic Manila to justify expelling or converting Bruneian Muslim colonists who supported their Manila vassals while his Mexican grandson Juan de Salcedo had a romantic relationship with Kandarapa, a princess of Tondo.[41] López de Legazpi had the local royalty executed or exiled after the failure of the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas, a plot in which an alliance of datus, rajahs, Japanese merchants, and the Sultanate of Brunei would band together to execute the Spaniards, along with their Latin American recruits and Visayan allies. The victorious Spaniards made Manila the capital of the Spanish East Indies and of the Philippines, which their empire would control for the next three centuries. In 1574, Manila was besieged by the Chinese pirate Lim Hong, who was thwarted by local inhabitants. Upon Spanish settlement, Manila was immediately made, by papal decree, a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Mexico. By royal decree of Philip II of Spain, Manila was put under the spiritual patronage of Saint Pudentiana and Our Lady of Guidance.[a]

Manila became famous for its role in the Manila–Acapulco galleon trade, which lasted for more than two centuries and brought goods from Europe, Africa, and Hispanic America across the Pacific Islands to Southeast Asia, and vice versa. Silver that was mined in Mexico and Peru was exchanged for Chinese silk, Indian gems, and spices from Indonesia and Malaysia. Wine and olives grown in Europe and North Africa were shipped via Mexico to Manila.[42] Because of the Ming ban on trade leveled against the Ashikaga shogunate in 1549, this resulted in the ban of all Japanese people from entering China and of Chinese ships from sailing to Japan. Manila became the only place where the Japanese and Chinese could openly trade.[43] In 1606, upon the Spanish conquest of the Sultanate of Ternate, one of monopolizers of the growing of spice, the Spanish deported the ruler Sultan Said Din Burkat[44] of Ternate, along with his clan and his entourage to Manila, where they were initially enslaved and eventually converted to Christianity.[45] About 200 families of mixed Spanish-Mexican-Filipino and Moluccan-Indonesian-Portuguese descent from Ternate and Tidor followed him there at a later date.[46]

The city attained great wealth due to its location at the confluence of the Silk Road, the Spice Route, and the Silver Way.[47] Significant is the role of Armenians, who acted as merchant intermediaries that made trade between Europe and Asia possible in this area. France was the first nation to try financing its Asian trade with a partnership in Manila through Armenian khojas. The largest trade volume was in iron, and 1,000 iron bars were traded in 1721.[48] In 1762, the city was captured by Great Britain as part of the Seven Years' War, in which Spain had recently become involved.[49] The British occupied the city for twenty months from 1762 to 1764 in their attempt to capture the Spanish East Indies but they were unable to extend their occupation past Manila proper.[50] Frustrated by their inability to take the rest of the archipelago, the British withdrew in accordance with the Treaty of Paris signed in 1763, which brought an end to the war. An unknown number of Indian soldiers known as sepoys, who came with the British, deserted and settled in nearby Cainta, Rizal.[51][52]

The Chinese minority were punished for supporting the British, and the fortress city Intramuros, which was initially populated by 1,200 pure Spanish families and garrisoned by 400 Spanish troops,[53] kept its cannons pointed at Binondo, the world's oldest Chinatown.[54] The population of native Spaniards was concentrated in the southern part of Manila and in 1787, La Pérouse recorded one regiment of 1,300 Mexicans garrisoned at Manila,[55] and they were also at Cavite, where ships from Spain's American colonies docked at,[56] and at Ermita, which was thus-named because of a Mexican hermit who lived there. The Hermit-Priest's name was Juan Fernandez de Leon who was a Hermit in Mexico before relocating to Manila.[57] Priests weren't usually alone too since they often brought along Lay Brothers and Sisters. The years: 1603, 1636, 1644, 1654, 1655, 1670, and 1672; saw the deployment of 900, 446, 407, 821, 799, 708, and 667 Latin-American soldiers from Mexico at Manila.[58] The Philippines hosts the only Latin-American-established districts in Asia.[59][60] The Spanish evacuated Ternate and settled Papuan refugees in Ternate, Cavite, which was named after their former homeland.[61] In 1603, Manila was also home to 25,000 Chinese[62]: 260 and housed 14,437 native (Malay-Filipino) families, as well as 3,528 mixed Spanish-Filipino families.[62]: 539

The rise of Spanish Manila marked the first time all hemispheres and continents were interconnected in a worldwide trade network, making Manila, alongside Mexico City and Madrid, the world's original set of global cities.[63] A Spanish Jesuit priest commented due to the confluence of many foreign languages in Manila, the confessional in Manila was "the most difficult in the world".[64][65] Juan de Cobo, another Spanish missionary of the 1600s, was so astonished by the commerce, cultural complexity, and ethnic diversity in Manila he wrote to his brethren in Mexico:

The diversity here is immense such that I could go on forever trying to differentiate lands and peoples. There are Castilians from all provinces. There are Portuguese and Italians; Dutch, Greeks and Canary Islanders, and Mexican Indians. There are slaves from Africa brought by the Spaniards [Through America], and others brought by the Portuguese [Through India]. There is an African Moor with his turban here. There are Javanese from Java, Japanese and Bengalese from Bengal. Among all these people are the Chinese whose numbers here are untold and who outnumber everyone else. From China there are peoples so different from each other, and from provinces as distant, as Italy is from Spain. Finally, of the mestizos, the mixed-race people here, I cannot even write because in Manila there is no limit to combinations of peoples with peoples. This is in the city where all the buzz is. (Remesal, 1629: 680–1)[66]

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the Spanish crown began to directly govern Manila.[67] Under direct Spanish rule, banking, industry, and education flourished more than they had in the previous two centuries.[68] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 facilitated direct trade and communications with Spain. The city's growing wealth and education attracted indigenous peoples, Negritos, Malays, Africans, Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Europeans, Latinos and Papuans from the surrounding provinces,[69] and facilitated the rise of an ilustrado class who espoused liberal ideas, which became the ideological foundations of the Philippine Revolution, which sought independence from Spain. A revolt by Andres Novales was inspired by the Latin American wars of independence but the revolt itself was led by demoted Latin-American military officers stationed in the city from the newly independent nations of Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Costa Rica.[70] Following the Cavite Mutiny and the Propaganda Movement, the Philippine revolution began; Manila was among the first eight provinces to rebel and their role was commemorated on the Philippine Flag, on which Manila was represented by one of the eight rays of the symbolic sun.[71]

American invasion era

After the 1898 Battle of Manila, Spain ceded the city to the United States. The First Philippine Republic based in nearby Bulacan fought against the Americans for control of the city.[72] The Americans defeated the First Philippine Republic and captured its president Emilio Aguinaldo, who pledged allegiance to the U.S. on April 1, 1901.[73] Upon drafting a new charter for Manila in June 1901, the U.S. officially recognized the city of Manila consisted of Intramuros and the surrounding areas. The new charter proclaimed Manila was composed of eleven municipal districts: Binondo, Ermita, Intramuros, Malate, Paco, Pandacan, Sampaloc, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Cruz, and Tondo. The Catholic Church recognized five parishes as parts of Manila; Gagalangin, Trozo, Balic-Balic, Santa Mesa, and Singalong; and Balut and San Andres were later added.[74]

Under U.S. control, a new, civilian-oriented Insular Government headed by Governor-General William Howard Taft invited city planner Daniel Burnham to adapt Manila to modern needs.[75] The Burnham Plan included the development of a road system, the use of waterways for transportation, and the beautification of Manila with waterfront improvements and construction of parks, parkways, and buildings.[76][77] The planned buildings included a government center occupying all of Wallace Field, which extends from Rizal Park to the present Taft Avenue. The Philippine capitol was to rise at the Taft Avenue end of the field, facing the sea. Along with buildings for government bureaus and departments, it would form a quadrangle with a central lagoon and a monument to José Rizal at the other end of the field.[78] Of Burnham's proposed government center, only three units—the Legislative Building, and the buildings of the Finance and Agricultural Departments—were completed before World War II began.

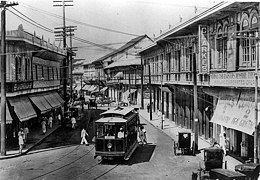

- Gallery of Manila during the American era

-

Plaza Moraga in the early 1900s

-

The Old Legislative Building featuring a Neoclassical style architecture.

-

Aerial view of Manila, 1936

Japanese occupation era

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, American soldiers were ordered to withdraw from Manila and all military installations were removed by December 24, 1941. Two days later, General Douglas MacArthur declared Manila an open city to prevent further death and destruction but Japanese warplanes continued bombing the city.[79] Japanese forces occupied Manila on January 2, 1942.[80]

From February 3 to March 3, 1945, Manila was the site of one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific theater of World War II. Under orders of Japanese Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, retreating Japanese forces killed about 100,000 Filipino civilians and perpetrated the mass rape of women in February.[81][82] At the end of the war, Manila had suffered from heavy bombardment and became the second-most-destroyed city of World War II.[83][84] Manila was recaptured by American and Philippine troops.

The postwar and independence era

After the war, reconstruction efforts started. Buildings like Manila City Hall, the Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts), and Manila Post Office were rebuilt, and roads and other infrastructures were repaired. In 1948, President Elpidio Quirino moved the seat of government of the Philippines to Quezon City, a new capital in the suburbs and fields northeast of Manila, which was created in 1939 during the administration of President Manuel L. Quezon.[85] The move ended any implementation of the Burnham Plan's intent for the government center to be at Luneta. When Arsenio Lacson became the first elected Mayor of Manila in 1952, before which all mayors were appointed, Manila underwent a "Golden Age",[86] regaining its pre-war moniker "Pearl of the Orient". After Lacson's term in the 1950s, Manila was led by Antonio Villegas for most of the 1960s. Ramon Bagatsing was mayor from 1972 until the 1986 People Power Revolution.[87]

During the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, Metro Manila was created as an integrated unit with the enactment of Presidential Decree No. 824 on November 7, 1975. The area encompassed four cities and thirteen adjoining towns as a separate regional unit of government.[88] On June 24, 1976, the 405th anniversary of the city's founding, President Marcos reinstated Manila as the capital of the Philippines for its historical significance as the seat of government since the Spanish Period.[89][90] At the same time, Marcos designated his wife Imelda Marcos as the first governor of Metro Manila. She started the rejuvenation of the city and re-branded Manila the "City of Man".[91]

The Martial Law era

Many of the key events of the historical period from the first major protests against the administration of Ferdinand Marcos in January 1970 until his ouster in February 1986 took place within the city of Manila. The first, the January 26, 1970, State of the Nation Address Protest which kicked off the "First Quarter Storm", took place at the Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts) on Padre Burgos Avenue,[92] and the very last saw the Marcos family flee Malacañang Palace into exile in the United States.[93][94][95]

The beginning weeks of Ferdinand Marcos' second term as president was marked by the 1969 balance of payments crisis, which economists trace to his first term tactic of using foreign loans to fund massive government projects in an effort to curry votes.[96][97][98] In protest, protest groups led mostly by students decided to picket Marcos' 1970 State of the Nation Address at the legislative building on January 26. The protesters were initially bickering amongst themselves because both moderate reformist and radical activist groups were present and fighting to gain control of the stage. But all of them, regardless of advocacy, were violently dispersed by the Philippine Constabulary.[99][100] This was followed by six more major protests which were violently dispersed, from the end of January until March 17, 1970.[94]

Instability continued the following year, with the most significant incident being the August 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing caused nine deaths and injured 95 others, including many prominent Liberal Party politicians including incumbent Senators Jovito Salonga, Eddie Ilarde, Eva Estrada-Kalaw, and Liberal Party president Gerardo Roxas, Sergio Osmeña Jr., Manila 2nd District Councilor Ambrosio "King" Lorenzo Jr., and Congressman Ramon Bagatsing who was the party's mayoral candidate for Manila.[100]

Marcos reacted to the bombing by blaming the still nascent Communist Party of the Philippines and then suspending of the writ of Habeas Corpus. The suspension is noted for forcing many members of the moderate opposition, including figures like Edgar Jopson, to join the ranks of the radicals. In the aftermath of the bombing, Marcos lumped all of the opposition together and referred to them as communists, and many former moderates fled to the mountain encampments of the radical opposition to avoid being arrested by Marcos' forces. Those who became disenchanted with the excesses of the Marcos administration and wanted to join the opposition after 1971 often joined the ranks of the radicals, simply because they represented the only group vocally offering opposition to the Marcos government.[101][102]

Marcos' declaration of martial law in September 1972 saw the immediate shutdown of all media not approved by Marcos, including Quezon City media outlets, including the Manila-based Manila Times, Philippines Free Press, The Manila Tribune and the Philippines Herald. At the same time, it saw the arrest of many students, journalists, academics, and politicians who were considered political threats to Marcos, many of them residents of the City of Manila. The first one was Ninoy Aquino who was arrested just before midnight on September 22 while at a hotel on UN Avenue preparing for a senate committee session the following morning.[100]

About 400 prominent critics of the Marcos administration were jailed in the first few hours of September 23 alone, and eventually about 70,000 individuals became Political detainees under the Marcos dictatorship - most of them arrested without warrants, which is why they were called detainees rather than prisoners.[103][104] At least 11,103 of them have since been officially recognized by the Philippine government as having been extensively tortured and abused.[105][106] and in April 1973 Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila student journalist Liliosa Hilao became the first of these detainees to be killed while in prison[107] - one of 3,257 known extrajudicial killings during the last 14 years of Marcos' presidency.[108]

In 1975, Marcos formalized the creation of a region called Metropolitan Manila, incorporating the four cities of Manila, Quezon City, Caloocan, Pasay, and the thirteen municipalities of Las Piñas, Makati, Malabon, Mandaluyong, Marikina, Muntinlupa, Navotas, Parañaque, Pasig, Pateros, San Juan, Taguig, and Valenzuela. And then he appointed his wife Imelda Marcos, who had been angered by the revelation of his dalliances during the Dovie Beams scandal, Governor of Metro Manila.[109]

Despite Marcos' declaration of martial law, poverty and other social issues persisted, so even with the military in his control, Marcos could not hold back the unrest. A major turning point was reached in Tondo in the form of the 1975 La Tondeña Distillery strike which was one of the first major open acts of resistance against the Marcos dictatorship which paved the way for similar protest actions elsewhere in the country.[110] From then, Manila continued to be a center of resistance activity; youth and student demonstrators repeatedly clashed with the police and military.[111]

Another major protest was the September 1984 Welcome Rotonda protest dispersal at the border of Manila and Quezon City, which came in the wake of the Aquino assassination the year before in 1983. International pressure had forced Marcos to give the press more freedom, so coverage exposed Filipinos to how opposition figures including 80-year-old former Senator Lorenzo Tañada and 71-year old Manila Times founder Chino Roces were waterhosed despite their frailty and how student leader Fidel Nemenzo (later Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Diliman) was shot nearly to death.[112][113][114]

The People Power revolution

In late 1985, in the face of escalating public discontent and under pressure from foreign allies, Marcos called a snap election with more than a year left in his term, selecting Arturo Tolentino as his running mate. The opposition to Marcos united behind Ninoy's widow Corazon Aquino and her running mate, Salvador Laurel.[115][116] The elections were held on February 7, 1986, an exercise marred by widespread reports of violence and tampering of election results.[117]

On February 16, 1986, Corazon Aquino held the "Tagumpay ng Bayan" (People's Victory) rally at Luneta Park, announcing a civil disobedience campaign and calling for her supporters to boycott publications and companies which were associated with Marcos or any of his cronies.[118] The event was attended by a crowd of about two million people.[119] Aquino's camp began making preparations for more rallies, and Aquino herself went to Cebu to rally more people to their cause.[120]

In the aftermath of the election and the revelations of irregularities, Juan Ponce Enrile and the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) - a cabal of disgruntled officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP)[121] - set into motion a coup attempt against Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.[122] Enrile and RAM's coup was quickly uncovered, which prompted Enrile to ask for the support of Philippine Constabulary chief Fidel Ramos. Ramos agreed to join Enrile but even so, their combined forces were trapped in Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo, and were about to be overrun by Marcos loyalist forces.[123][124][125] Discovering what was happening, the forces which had been organizing Aquino's civil disobedience campaign went to the stretch of Efipanio De Los Santos Avenue (EDSA) between the two camps, beginning to form a human barricade to keep Marcos loyalist forces from attacking. The crowd grew even larger when Ramos telephoned Manila Cardinal Jaime Sin for help, and Sin went on Radyo Veritas to invite Catholics to join in protecting Enrile and Ramos.[126] Seeing what was happening, multiple units of the Armed Forces of the Philippines defected Marcos, with air units under the command of General Antonio Sotelo and Colonel Charles Hotchkiss, even performed calculated operations which included strafing the grounds of Malacañang palace with bullets and disabling gunships at nearby Villamor Airbase.[123]

The Reagan administration eventually decided to offer Marcos a chance to flee into exile. Shortly after midnight on February 26, 1986, the Marcos Family fled Malacañang and were taken to Clark Airbase, after which they went into exile in Honolulu along with some select followers including Fabian Ver and Danding Cojuangco.[93] Because the victory had been won by the civilians on the streets rather than the military, the event was dubbed the People Power revolution. Ferdinand Marcos' 21 years as President - and his 14 years as authoritarian leader - of the Philippines was over.[93][124]

Contemporary

From 1986 to 1992, Mel Lopez was mayor of Manila, first due to presidential designation, before being elected in 1988.[127] In 1992, Alfredo Lim was elected mayor, the first Chinese-Filipino to hold the office. He was known for his anti-crime crusades. Lim was succeeded by Lito Atienza, who served as his vice mayor, and was known for his campaign and slogun "Buhayin ang Maynila" (Revive Manila), which saw the establishment of several parks, and the repair and rehabilitation of the city's deteriorating facilities. He was the city's mayor for nine years before being termed out of office. Lim once again ran for mayor and defeated Atienza's son Ali in the 2007 city election, and immediately reversed all of Atienza's projects,[128] which he said made little contribution to the improvements of the city. The relationship of both parties turned bitter, with them both contesting the 2010 city elections, which Lim won. Lim was sued by councilor Dennis Alcoreza on 2008 over human rights,[129] he was charged with graft over the rehabilitation of public schools.[130]

In 2012, DMCI Homes began constructing Torre de Manila, which became controversial for ruining the sight line of Rizal Park.[131] The tower became known as "Terror de Manila" and the "national photobomber",[132] and became a sensationalized heritage issue. In 2017, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines erected a "comfort woman" statue on Roxas Boulevard, causing Japan to express regret about the statue's erection despite the healthy relationship between Japan and the Philippines.[133][134]

In the 2013 election, former President Joseph Estrada succeeded Lim as the city's mayor. During his term, Estrada allegedly paid ₱5 billion in city debts and increased the city's revenues. In 2015, in line with President Noynoy Aquino's administration progress, the city became the most-competitive city in the Philippines. In the 2016 elections, Estrada narrowly won over Lim.[135] Throughout Estrada's term, numerous Filipino heritage sites were demolished, gutted, or approved for demolition; these include the post-war Santa Cruz Building, Capitol Theater, El Hogar, Magnolia Ice Cream Plant, and Rizal Memorial Stadium.[136][137][138] Some of these sites were saved after the intervention of governmental cultural agencies and heritage advocate groups.[139] In May 2019, Estrada said Manila was debt-free;[140] two months later, however, the Commission on Audit said Manila was ₱4.4 billion in debt.[141]

Estrada, who was seeking for re-election for his third and final term, lost to Isko Moreno in the 2019 local elections.[142][143] Moreno has served as the vice mayor under both Lim and Estrada. Estrada's defeat was seen as the end of their reign as a political clan, whose other family members run for national and local positions.[144] After assuming office, Moreno initiated a city-wide cleanup of illegal vendors, signed an executive order promoting open governance, and vowed to stop bribery and corruption in the city.[145] Under his administration, several ordinances were signed, giving additional perks and privileges to Manila's elderly people,[146] and monthly allowances for Grade 12 Manileño students in all public schools in the city, including students of Universidad de Manila and the University of the City of Manila.[147][148]

In 2022, Time Out ranked Manila in 34th position in its list of the 53 best cities in the world, citing it as "an underrated hub for art and culture, with unique customs and cuisine to boot". Manila was also voted the third-most-resilient and least-rude city for the year's index.[149][150] In 2023, the search site Crossword Solm utilizing internet geotagging, showed that Manila is the world's most loving capital city.[151]

In August 2023, President Bongbong Marcos suspended all reclamation projects in Manila Bay, including those in the City of Manila.[152] However, the city has no objections and is willing to pursue the suspended reclamation projects.[153]

Geography

The City of Manila is situated on the eastern shore of Manila Bay, on the western coast of Luzon, 1,300 km (810 mi) from mainland Asia.[154] The protected harbor on which Manila lies is regarded as the finest in Asia.[155] The Pasig River flows through the middle of city, dividing it into north and south.[156][157] The overall grade of the city's central, built-up areas is relatively consistent with the natural flatness of the natural geography, generally exhibiting only slight differentiation.[158]

Almost all of Manila sits on top prehistoric alluvial deposits built by the waters of the Pasig River and on land reclaimed from Manila Bay. Manila's land has been substantially altered by human intervention; there has been considerable land reclamation along the waterfronts since the early-to-mid twentieth century. Some of the city's natural variations in topography have been leveled. As of 2013, Manila had a total area of 42.88 square kilometres (16.56 sq mi).[156][157]

In 2017, the City Government approved five reclamation projects; the New Manila Bay–City of Pearl (New Manila Bay International Community) (407.43 hectares (1,006.8 acres)), Solar City (148 hectares (370 acres)), Manila Harbour Center expansion (50 hectares (120 acres)), Manila Waterfront City (318 hectares (790 acres)),[159] and Horizon Manila (419 hectares (1,040 acres)). Of the five planned projects, only Horizon Manila was approved by the Philippine Reclamation Authority in December 2019 and was scheduled for construction in 2021.[160] Another reclamation project is possible and when built, it will include in-city housing relocation projects.[161] Environmental activists and the Catholic Church have criticized the land reclamation projects, saying they are not sustainable and would put communities at risk of flooding.[162][163] In line of the upcoming reclamation projects, the Philippines and the Netherlands agreed to a cooperation on the ₱250 million Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan to oversee future decisions on projects on Manila Bay.[164]

Barangays and districts

Manila is made up of 897 barangays,[165] which are grouped into 100 zones for statistical convenience. Manila has the most barangays of any metropolis in the Philippines.[166] Due to a failure to hold a plebiscite, attempts at reducing its number have not succeeded despite local legislation—Ordinance 7907, passed on April 23, 1996—reducing the number from 896 to 150 by merging existing barangays.[167]

- District I (2020 population: 441,282)[168] covers the western part of Tondo and is made up of 136 barangays. It is the most-densely populated Congressional District and was also known as Tondo I. The district includes one of the biggest urban-poor communities. Smokey Mountain on Balut Island was once known as the country's largest landfill where thousands of impoverished people lived in slums. After the closure of the landfill in 1995, mid-rise housing was built on the site. This district also contains the Manila North Harbor Center, Manila North Harbor, and Manila International Container Terminal of the Port of Manila. The boundaries of the 1st District are the neighboring cities Navotas and the southern enclave of Caloocan.

- District II (2020 population: 212,938)[168] covers the eastern part of Tondo and contains 122 barangays. It is also referred to as Tondo II. It includes Gagalangin, a prominent place in Tondo, and Divisoria, a popular shopping area and the site of the Main Terminal Station of the Philippine National Railways. The boundary of the 2nd District is the neighboring city Caloocan.

- District III (2020 population: 220,029)[168] covers Binondo, Quiapo, San Nicolas and Santa Cruz. It contains 123 barangays and includes "Downtown Manila", the historic business district of the city, and the oldest Chinatown in the world. The boundary of the 3rd District is the neighboring city Quezon City.

- District IV (2020 population: 277,013)[168] covers Sampaloc and some parts of Santa Mesa. It contains 192 barangays and has numerous colleges and universities, which were located along the city's "University Belt", a de facto sub-district. The University of Santo Tomas, the oldest-existing university in Asia, which was established in 1611. The boundaries of the 4th District are the neighboring cities San Juan and Quezon City. The Institution was home to at least 30 Catholic Saints.[169][170]

- District V (2020 population: 395,065)[168] covers Ermita, Malate, Port Area, Intramuros, San Andres Bukid, and a portion of Paco. It is made up of 184 barangays. The historic Walled City is located here, along with Manila Cathedral and San Agustin Church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The boundaries of the 5th District are the neighboring cities Makati and Pasay. This district also includes the Manila South Cemetery, an exclave surrounded by Makati City.

- District VI (2020 population: 300,186)[168] covers Pandacan, San Miguel, Santa Ana, Santa Mesa, and a portion of Paco. It contains 139 barangays. Santa Ana district is known for its 18th Century Santa Ana Church and historic ancestral houses. The boundaries of the 6th District are the neighboring cities Makati, Mandaluyong, Quezon City, and San Juan.

| District name | Legislative District number |

Area | Population (2020)[171] |

Density | Barangays | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | /km2 | /sq mi | ||||

| Binondo | 3 | 0.6611 | 0.2553 | 20,491 | 31,000 | 80,000 | 10 |

| Ermita | 5 | 1.5891 | 0.6136 | 19,189 | 12,000 | 31,000 | 13 |

| Intramuros | 5 | 0.6726 | 0.2597 | 6,103 | 9,100 | 24,000 | 5 |

| Malate | 5 | 2.5958 | 1.0022 | 99,257 | 38,000 | 98,000 | 57 |

| Paco | 5 & 6 | 2.7869 | 1.0760 | 79,839 | 29,000 | 75,000 | 43 |

| Pandacan | 6 | 1.66 | 0.64 | 84,769 | 51,000 | 130,000 | 38 |

| Port Area | 5 | 3.1528 | 1.2173 | 72,605 | 23,000 | 60,000 | 5 |

| Quiapo | 3 | 0.8469 | 0.3270 | 29,846 | 35,000 | 91,000 | 16 |

| Sampaloc | 4 | 5.1371 | 1.9834 | 388,305 | 76,000 | 200,000 | 192 |

| San Andres | 5 | 1.6802 | 0.6487 | 133,727 | 80,000 | 210,000 | 65 |

| San Miguel | 6 | 0.9137 | 0.3528 | 18,599 | 20,000 | 52,000 | 12 |

| San Nicolas | 3 | 1.6385 | 0.6326 | 42,957 | 26,000 | 67,000 | 15 |

| Santa Ana | 6 | 1.6942 | 0.6541 | 203,598 | 120,000 | 310,000 | 34 |

| Santa Cruz | 3 | 3.0901 | 1.1931 | 126,735 | 41,000 | 110,000 | 82 |

| Santa Mesa | 6 | 2.6101 | 1.0078 | 111,292 | 43,000 | 110,000 | 51 |

| Tondo | 1 & 2 | 8.6513 | 3.3403 | 654,220 | 76,000 | 200,000 | 259 |

| |||||||

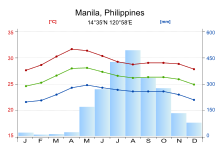

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification system, Manila has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am), closely bordering on a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw). Together with the rest of the Philippines, Manila lies entirely within the tropics. Its proximity to the equator means temperatures are high year-round especially during the daytime, rarely going below 19 °C (66.2 °F) or above 39 °C (102.2 °F). Temperature extremes have ranged from 14.5 °C (58.1 °F) on January 11, 1914,[172] to 38.6 °C (101.5 °F) on May 7, 1915.[173]

Humidity levels are usually very high all year round, making the air feel hotter than its actual temperature. Manila has a distinct dry season lasting from late December through early April, and a relatively lengthy wet season that covers the remaining period with slightly cooler daytime temperatures. In the wet season, rain rarely falls all day but rainfall is very heavy for short periods. Typhoons usually occur from June to September.[174]

| Climate data for Port Area, Manila (1991–2020, extremes 1885–2024) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.5 (97.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

38.8 (101.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.6 (96.1) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.8 (101.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

32.1 (89.8) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 19.4 (0.76) |

21.9 (0.86) |

21.8 (0.86) |

23.4 (0.92) |

159.1 (6.26) |

253.3 (9.97) |

432.3 (17.02) |

476.1 (18.74) |

396.4 (15.61) |

220.6 (8.69) |

119.9 (4.72) |

98.5 (3.88) |

2,242.7 (88.30) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 124 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 70 | 67 | 66 | 72 | 76 | 80 | 82 | 81 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 177 | 198 | 226 | 258 | 223 | 162 | 133 | 133 | 132 | 158 | 153 | 152 | 2,105 |

| Source 1: PAGASA[175][176] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun, 1931–1960)[177] | |||||||||||||

Natural hazards

Swiss Re ranked Manila as the second-riskiest capital city to live in, citing its exposure to natural hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, typhoons, floods, and landslides.[18] The seismically active Marikina Valley Fault System poses a threat of a large-scale earthquake with an estimated magnitude of between 6 and 7, and as high as 7.6[178] to Metro Manila and nearby provinces.[179] Manila has experienced several deadly earthquakes, notably those of 1645 and 1677, which destroyed the stone-and-brick medieval city.[180] Architects during the Spanish colonial period used the Earthquake Baroque style to adapt to the region's frequent earthquakes.[181]

Manila experiences between five and seven typhoons each year.[182] In 2009, Typhoon Ketsana (Ondoy) struck the Philippines, leading to one of the worst floods in Metro Manila and several provinces in Luzon with an estimated damages worth ₱11 billion (US$237 million),[183][184] and caused 448 deaths in Metro Manila alone. Following the aftermath of Typhoon Ketsana, the city began to dredge its rivers and improve its drainage network.

Parks and green spaces

Metro Manila is situated in a variety of ecosystems including upland forests, mangrove forests, mudflats, sandy beaches, sea grass meadows and coral reefs. Metro Manila is home to urban parks, nature parks, plazas, nature reserves, and an arboretum. However, according to the Asian Green City Index, in 2007 Manila contained only an average of 4.5 square meters (48 sq ft) of green space per person, well below the index average of 39 square meters (420 sq ft)[186] and below the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended minimum of 9 square meters (97 sq ft) per person.[187][188]

The Arroceros Forest Park is a 2.2-hectare (5.4-acre) nature park situated in the heart of downtown Manila along the south bank of the Pasig River. Considered as the "last lung of Manila", the park was professionally planned in 1993 with its secondary growth forest of 61 different native tree varieties and 8,000 ornamental plants providing a habitat for about 10 different bird species.[189]

Pollution

Air pollution in Manila is due to industrial waste and automobiles.[190][191] Swiss firm IQAir reported in December 2020 Manila experienced an average PM2.5 concentration of 6.1×10−6 g/m3 (1.03×10−8 lb/cu yd), which is classed as "Good" according to recommendations made by the World Health Organization.[192]

According to a report in 2003, the Pasig River is one of the most-polluted rivers in the world in which 150 metric tons (150 long tons; 170 short tons) of domestic waste and 75 metric tons (74 long tons; 83 short tons) of industrial waste are dumped daily.[193][needs update] The city is the second-biggest waste producing metropolis in the country with 1,151.79 tons (7,500.07 cubic meters (264,862 cu ft)) per day, after Quezon City, which produces 1,386.84 tons (12,730.59 cubic meters (449,577 cu ft)) per day. Both cities were cited as having poor management in garbage collection and disposal.[194]

Rehabilitation efforts have resulted in the creation of parks along the riverside and stricter pollution controls.[195][196] In 2019, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources launched a rehabilitation program for Manila Bay that will be administered by different government agencies.[197][198]

Cityscape

Manila is a planned city. In 1905, American architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham was commissioned to design the new capital.[199] His design for the city was based on the City Beautiful movement, which favored broad streets and avenues radiating out from rectangles. Manila is made up of fourteen city districts, according to Republic Act No. 409—the Revised Charter of the City of Manila—the basis of which officially sets the present-day boundary of the city.[10] The districts Santa Mesa, which was partitioned from Sampaloc,[200] and San Andres, which was partitioned off from Santa Ana, were later created.

Manila's mix of architectural styles reflects its, and the Philippines', turbulent history. During World War II, Manila was razed to the ground by Japanese forces and the shelling of American forces.[201][202] After the war ended, rebuilding began and most of the historical buildings were reconstructed. Many of the historic churches and buildings in Intramuros, Manila's historic core, however, had been damaged beyond repair.[203] Manila's current urban landscape is one of modern and contemporary architecture. Manila's historic sites under the entry of The Walled City and Historic Monuments of Manila is currently being proposed to the tentative list for future UNESCO World Heritage Site inscription.[204]

Architecture

Manila is known for its eclectic mix of architecture that includes a wide range of styles spanning the city's historical and cultural periods. Its architectural styles reflect American, Spanish, Chinese, and Malay influences.[205] Prominent Filipino architects including Antonio Toledo,[206] Felipe Roxas,[207] Juan M. Arellano[208] and Tomás Mapúa have designed significant buildings in Manila such as churches, government offices, theaters, mansions, schools, and universities.[209]

Manila is known for its Art Deco theaters, some of which were designed by Juan Nakpil and Pablo Antonio.[210] The historic Escolta Street in Binondo has many buildings of Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts architectural styles, many of which were designed by prominent Filipino architects during the American colonial period between the 1920s and the late 1930s. Many architects, artists, historians, and heritage advocacy groups are campaigning for the restoration of Escolta Street, which was once the premier street of the Philippines.[211]

Almost all of Manila's pre-war and Spanish colonial architecture was destroyed during the 1945 Battle of Manila by intensive bombardment by the United States Air Force. Reconstruction took place afterward, replacing the destroyed historic Spanish-era buildings with modern ones, erasing much of the city's character. Some of the destroyed buildings, such as the Old Legislative Building (now the National Museum of Fine Arts), Ayuntamiento de Manila (now the Bureau of the Treasury), and the under-construction San Ignacio Church and Convent (as the Museo de Intramuros), have been reconstructed. There are plans to refurbish and restore several neglected historic buildings and places such as Plaza Del Carmen, San Sebastian Church, and the NCCA Metropolitan Theater. Spanish-era shops and houses in the districts of Binondo, Quiapo, and San Nicolas are also planned to be restored as a part of a movement to restore the city to its pre-war state.[212][213]

Because Manila is prone to earthquakes, Spanish colonial architects invented a style called Earthquake Baroque, which churches and government buildings during the Spanish colonial period adopted.[181] As a result, succeeding earthquakes of the 18th and 19th centuries barely affected Manila, although they periodically leveled the surrounding area. Modern buildings in and around Manila are designed or have been retrofitted to withstand an 8.2 magnitude quake in accordance with the country's building code.[214]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 219,928 | — |

| 1918 | 285,306 | +1.75% |

| 1939 | 623,492 | +3.79% |

| 1948 | 983,906 | +5.20% |

| 1960 | 1,138,611 | +1.22% |

| 1970 | 1,330,788 | +1.57% |

| 1975 | 1,479,116 | +2.14% |

| 1980 | 1,630,485 | +1.97% |

| 1990 | 1,601,234 | −0.18% |

| 1995 | 1,654,761 | +0.62% |

| 2000 | 1,581,082 | −0.97% |

| 2007 | 1,660,714 | +0.68% |

| 2010 | 1,652,171 | −0.19% |

| 2015 | 1,780,148 | +1.43% |

| 2020 | 1,846,513 | +0.72% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[215][216][217][218][219] | ||

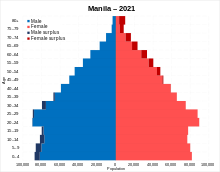

According to the 2020 Philippine census, Manila has a population of 1,846,513 people, making it the second-most-populous city in the Philippines.[220] Manila is the most-densely populated city in the world, with 41,515 inhabitants per km2 in 2015.[6] District 6 is listed as the densest with 68,266 inhabitants per km2, followed by District 1 with 64,936 and District 2 with 64,710. District 5 is the least-densely populated area with 19,235.[221]

Manila has been presumed to be the Philippines' largest city since the establishment of a permanent Spanish settlement, and eventually became the political, commercial, and ecclesiastical capital of the country.[222] Since colonial times, Manila has been the destination of peoples whose origins are as wide-ranging as India[223] and Latin America.[224] Practicing forensic anthropology, while exhuming cranial bones in several Philippine cemeteries, researcher Matthew C. Go estimated that 7% of the mean amount, among the samples exhumed, have attribution to European descent.[225] Research work published in the Journal of Forensic Anthropology, collating contemporary Anthropological data show that the percentage of Filipino bodies who were sampled from the University of the Philippines, that is phenotypically classified as Asian (East, South and Southeast Asian) is 72.7%, Hispanic (Spanish-Amerindian Mestizo, Latin American, and/or Spanish-Malay Mestizo) is at 12.7%, Indigenous American (Native American) at 7.3%, African at 4.5%, and European at 2.7%.[226] Between the 1860s and 1890s, in urban areas of the Philippines – especially Manila – according to burial statistics, as much as 3.3% of the population were pure European Spaniards and pure Chinese composed 9.9% of the city's populace. The Spanish-Filipino and Chinese-Filipino Mestizo populations also fluctuated, with the mixed Spanish-Filipinos composing 19% of Manila's population.[62]: 539 Eventually, these non-native categories diminished because they were assimilated into the majority Austronesian Filipino population.[227] During the Philippine Revolution, the term "Filipino" included people of any race born in the Philippines.[228][229] This explains the abrupt drop of the proportion of Chinese, Spanish, and Mestizo peoples across the country by the time of the first American census in 1903, as the foreign and mixed descended peoples identified solely as pure Filipinos.[230] Manila's population dramatically increased since the 1903 census because people tended to move from rural areas to towns and cities. In the 1960 census, Manila became the first Philippine city to exceed one million people – more than five times of its 1903 population. The city continued to grow until the population stabilized at 1.6 million and experienced alternating increases and decreases starting in the 1990 census year. This phenomenon may be attributed to the higher growth experienced by suburbs and the already-very-high population density of the city. As such, Manila exhibited a decreasing percentage share of the metropolitan population[231] from 63% in the 1950s to 27.5%[232] in 1980, and 13.8% in 2015. The much-larger Quezon City marginally surpassed the population of Manila in 1990 and by the 2015 census it already has 1.1 million more people. Nationally, the population of Manila was expected to be overtaken by cities with larger territories such as Caloocan and Davao City by 2020.[233] The vernacular language is Filipino, which is mostly based on the Tagalog language of the city and its surroundings, and this Manilan form of spoken Tagalog has become the lingua franca of the Philippines, having spread throughout the archipelago through mass media and entertainment. English is the language most widely used in education and business, and is in heavy everyday use throughout Metro Manila and the rest of the Philippines.

Philippine Hokkien, which is locally known as Lan-nang-oe, a variant of Southern Min, is mainly spoken by the city's Chinese-Filipino community. According to data provided by the Bureau of Immigration, 3.12 million Chinese citizens arrived in the Philippines from January 2016 to May 2018.[234]

Crime

Crime in Manila is concentrated in areas that are associated with poverty, drug abuse, and gangs. Crime in the city is also directly related to its changing demographics and unique criminal justice system. The illegal drug trade is a major problem of the city; in Metro Manila alone, 92% of the barangays were affected by illegal drugs in February 2015.[235]

From 2010 to 2015, Manila had the second-highest index crime rates in the Philippines, with 54,689 cases or an average of about 9,100 cases per year.[236] By October 2017, Manila Police District (MPD) reported a 38.7% decrease in index crimes from 5,474 cases in 2016 to 3,393 in 2017. MPD's crime-solution efficiency also improved; six-to-seven of every ten crimes were solved by the city police force.[237] MPD was cited as the Best Police District in Metro Manila in 2017 for registering the highest crime-solution efficiency.[238]

Religion

Religion in Manila (circa 2010)[239]

Christianity

As a result of Spanish cultural influence, Manila is a predominantly Christian city. As of 2010, 93.5% of the population were Roman Catholic, 1.9% were adherents of the Iglesia ni Cristo, 1.8% followed various Protestant, and 1.1% were Buddhists. Members of Islam and other religions make up the remaining 1.4% of the population.[239]

Manila is the seat of prominent Catholic churches and institutions. There are 113 Catholic churches within the city limits; 63 of which are considered major shrines, basilicas, or cathedrals.[240] Manila Cathedral, the country's oldest established church, is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila.[241] There are another three basilicas in the city; Quiapo Church, Binondo Church, and the Minor Basilica of San Sebastián.[242]San Agustín Church in Intramuros is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[243]

Several Mainline Protestant denominations are headquartered in the city. St. Stephen's Parish pro-cathedral in Santa Cruz district is the see of the Episcopal Church in the Philippines' Diocese of Central Philippines, while on Taft Avenue are the main cathedral and central offices of Iglesia Filipina Independiente (also called the Aglipayan Church), a nationalist church that is a product of the Philippine Revolution. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has a temple within Manila, one of two operating LDS temples in the Philippines.

The indigenous Iglesia ni Cristo has several locales (akin to parishes) in the city, including its first chapel, now a museum, in Punta, Santa Ana.[244] Evangelical, Pentecostal and Seventh-day Adventist denominations also thrive. The headquarters of the Philippine Bible Society is in Manila. The main campus of the Cathedral of Praise is located on Taft Avenue. Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide has several branches and campuses in Manila.

Religious groups such as Members Church of God International (MCGI),[245] Iglesia ni Cristo, Jesus Is Lord Church Worldwide, and the El Shaddai movement celebrate their anniversaries at Quirino Grandstand, which is an open space in Rizal Park.[246]

-

Manila Cathedral is the seat of Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila.

-

Binondo Church serves the Roman Catholic Chinese community.

-

Quiapo Church, home of the iconic Black Nazarene, whose Traslacion feast is celebrated every January 9

Other faiths

Manila has many Taoist and Buddhist temples like Seng Guan Temple that serve the spiritual needs of the Chinese Filipino community.[248] Quiapo has a "Muslim town" that includes the city's largest mosque Masjid Al-Dahab.[249] Members of the Indian expatriate community can worship at the large Hindu temple in the city or at the Sikh gurdwara on United Nations Avenue. The Baháʼí Faith's governing body in the Philippines the National Spiritual Assembly is headquartered near Manila's eastern boundary with Makati.[citation needed]

Economy

Manila is a major center for commerce, banking and finance, retailing, transportation, tourism, real estate, new media, traditional media, advertising, legal services, accounting, insurance, theater, fashion, and the arts. Around 60,000 establishments operate in the city.[250]

The National Competitiveness Council of the Philippines, which annually publishes the Cities and Municipalities Competitiveness Index (CMCI), ranks the country's cities, municipalities, and provinces according to their economic dynamism, government efficiency, and infrastructure. According to the 2022 CMCI, Manila was the second-most-competitive highly urbanized city in the Philippines.[251] Manila held the title of the country's most-competitive city in 2015, and since then has been in the top three, denoting Manila is consistently one of the best place to live in and do business.[252]

Binondo, the oldest and one of the largest Chinatowns in the world, was the center of commerce and business activities in the city. Numerous residential and office skyscrapers occupy its medieval streets. As of 2013, plans by the city government of Manila to turn the Chinatown area into a business process outsourcing (BPO) hub were in progress; thirty unoccupied buildings had been already identified for conversion into BPO offices. Most of these buildings are on Escolta Street, Binondo.[253]

The Port of Manila is the largest seaport in the Philippines and the main international shipping route into the country. The Philippine Ports Authority oversees the operation and management of the country's ports. International Container Terminal Services Inc., according to the Asian Development Bank, is one of the top-five major maritime terminal operators in the world,[254][255] and has its headquarters and main operations at the Port of Manila. Another port operator, Asian Terminal Incorporated, has its corporate office and main operations at Manila South Harbor, and its container depository is in Santa Mesa. Manila is classified as a Medium-Port Megacity, using the Southampton system for port-city classification.[256]

Manufacturers within the city produce industrial-related products such as chemicals, textiles, clothing, electronic goods, food, beverages, and tobacco products. Local businesses process primary commodities for export, including rope, plywood, refined sugar, copra, and coconut oil. The food-processing industry is one of the most-stable manufacturing sector in the city.[257]

Pandacan oil depot houses the storage facilities and distribution terminals of Caltex Philippines, Pilipinas Shell, and Petron Corporation; the major players in the country's petroleum industry. The oil depot has been a subject of various concerns, including its environmental and health impact on the residents of Manila. The Supreme Court ordered the oil depot to be relocated outside the city by July 2015,[258][259] but it failed to meet this deadline. Most of the oil depot facility inside the 33-hectare (82-acre) compound were demolished,[260] and plans have been made to convert it into a transport hub or food park.[261]

Manila is a major publishing center of the Philippines.[262] Manila Bulletin, the Philippines' largest broadsheet newspaper by circulation, is headquartered in Intramuros.[263] Other major publishing companies in the country The Manila Times, The Philippine Star, and Manila Standard Today are headquartered in the Port Area. The Chinese Commercial News, the Philippines' oldest existing Chinese-language newspaper, and the country's third-oldest newspaper,[264] is headquartered in Binondo. DWRK used to have its studio at the FEMS Tower 1 along Osmeña Highway in Malate before transferring to the MBC Building at the CCP Complex in 2008.[265]

Manila serves as the headquarters of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, which is located on Roxas Boulevard.[266] The Landbank of the Philippines and Philippine Trust Company also have their headquarters in Manila. Unilever Philippines used to have its corporate office on United Nations Avenue in Paco before transferring to Bonifacio Global City in 2016.[267] Vehicle manufacturer Toyota also has its regional office on UN Avenue.

Tourism

Manila welcomes over one million tourists each year.[262] Major tourist destinations include the historic Walled City of Intramuros, the Cultural Center of the Philippines Complex,[note 1] Manila Ocean Park, Binondo (Chinatown), Ermita, Malate, Manila Zoo, the National Museum Complex, and Rizal Park.[268] Both the historic Walled City of Intramuros and Rizal Park were designated as flagship destinations and as tourism enterprise zones in the Tourism Act of 2009.[269]

Rizal Park, also known as Luneta Park, is a national park and the largest urban park in Asia.[270] with an area of 58 hectares (140 acres),[271] The park was constructed to honor of the country's national hero José Rizal, who was executed by the Spaniards on charges of subversion. The flagpole west of the Rizal Monument is the Kilometer Zero marker for distances to locations across the country. The park is managed by the National Parks and Development Committee.[272]

The 0.67-square-kilometer (0.26 sq mi) Walled City of Intramuros is the historic center of Manila. It is administered by the Intramuros Administration, an attached agency of the Department of Tourism. It contains Manila Cathedral and the 18th Century San Agustin Church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Kalesa is a popular mode of transportation for tourists in Intramuros and nearby places including Binondo, Ermita and Rizal Park.[273] Binondo, the oldest Chinatown in the world, was established in 1521[274] and served as a hub of Chinese commerce before the Spaniards colonized the Philippines. Its main attractions are Binondo Church, Filipino-Chinese Friendship Arch, Seng Guan Buddhist Temple, and authentic Chinese restaurants.

Manila is designated as the country's leading destination for medical tourism, which is estimated to annually generate $1 billion in revenue.[275] Lack of a progressive health system, inadequate infrastructure, and the unstable political environment are seen as hindrances to its growth.[276]

Shopping

Manila is regarded as one of the best shopping destinations in Asia.[277][278] Major shopping malls, department stores, markets, supermarkets, and bazaars are located within the city.

Divisoria in Tondo has been locally described as a "shopping mecca" of Manila.[279][280] Shopping malls sell goods at bargain prices. Small vendors occupy several roads, causing pedestrian and vehicular traffic. A well-known landmark in Divisoria is the Tutuban Center, a large shopping mall that is a part of the Philippine National Railways' Main Station. It attracts 1 million people every month and is expected to add another 400,000 people upon the completion of the LRT Line 2 West Extension, making it Manila's busiest transfer station.[281] Another "lifestyle mall" is Lucky Chinatown. There are almost 1 million shoppers in Divisoria according to the Manila Police District.[282]

Binondo, the oldest Chinatown in the world,[54] is the city's center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, with a wide variety of shops and restaurants. Quiapo is referred to as the "Old Downtown", where tiangges, markets, boutique shops, music and electronics stores are common.[283] Many department stores are on Recto Avenue.

Robinsons Place Manila is Manila's largest shopping mall.[284] The mall was the second and the largest Robinsons Malls built. SM Supermalls operates the shopping malls SM City Manila and SM City San Lazaro. SM City Manila is located on the former site of YMCA Manila beside Manila City Hall in Ermita, while SM City San Lazaro is built on the site of the former San Lazaro Hippodrome in Santa Cruz. The building of the former Manila Royal Hotel in Quiapo, which is known for its revolving restaurant, is now the SM Clearance Center and was established in 1972.[285] The site of the first SM Department Store is Carlos Palanca Sr. (formerly Echague) Street in San Miguel.[286]

Culture

Museums

As the cultural center of the Philippines, Manila has a number of museums. The National Museum Complex of the National Museum of the Philippines, located in Rizal Park, is composed of the National Museum of Fine Arts, the National Museum of Anthropology, the National Museum of Natural History,[287] and the National Planetarium. Spoliarium, a famous painting by Juan Luna, can be found in the complex.[288]

The city hosts the National Library of the Philippines, a repository of the country's printed and recorded cultural heritage, and other literary and information resources.[289][290] The National Historical Commission of the Philippines maintains two history museums in the city, which are the Museo ni Apolinario Mabini – PUP and the Museo ni Jose Rizal – Fort Santiago.[291] Museums established or run by the National Library and by educational institutions such asDLS-CSB Museum of Contemporary Art and Design,[292] UST Museum of Arts and Sciences,[293] and the UP Museum of a History of Ideas are located in the city.[294]

Bahay Tsinoy, one of Manila's prominent museums, documents the lives of Chinese people and their contributions to the history of the Philippines.[295][296] Intramuros Light and Sound Museum chronicles Filipinos' desire for freedom during the revolution under Rizal's leadership and other revolutionary leaders. The Metropolitan Museum of Manila houses modern and contemporary visual arts, and exhibits Filipino arts and culture.[297]

Other museums in the city are the Museo Pambata,[298] a children's museum;[299] and Plaza San Luis, an outdoor heritage public museum that includes nine Spanish Bahay na Bato houses.[300] Ecclesiastical museums located in the city are the Parish of the Our Lady of the Abandoned in Santa Ana;[301] San Agustin Church Museum;[302] and the Museo de Intramuros, which houses the ecclesiastical art collection of the Intramuros Administration in the reconstructed San Ignacio Church and Convent.[303]

Sports

Sports in Manila have a long and distinguished history. The city's, and in general the country's, main sport is basketball. Most barangays have a basketball court or a makeshift one, and court markings are frequently drawn on the streets. Larger barangays have covered courts where inter-barangay leagues are held every April to May. Manila's major sports venues include Rizal Memorial Sports Complex and San Andres Gym, the base of the now-defunct Manila Metrostars.[304] Rizal Memorial Sports Complex houses a track and football stadium, a baseball stadium, tennis courts, Rizal Memorial Coliseum, and Ninoy Aquino Stadium; the latter two are indoor arenas. The Rizal complex had hosted several multi-sport events, such as the 1954 Asian Games and the 1934 Far Eastern Games. When the Philippines hosts the Southeast Asian Games, most of the events are held at the complex but in the 2005 Games, most events were held elsewhere. The 1960 ABC Championship and the 1973 ABC Championship, forerunners of the FIBA Asia Championship, were hosted at the memorial coliseum; the national basketball team won both tournaments.[305] The 1978 FIBA World Championship was held at the coliseum although the latter stages were held in the Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City.

Manila has several other well-known sports facilities such as Enrique M. Razon Sports Center and the University of Santo Tomas Sports Complex, both of which are private venues owned by a university; collegiate sports are also held in the city; the University Athletic Association of the Philippines and the National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball games held at Rizal Memorial Coliseum and Ninoy Aquino Stadium, although basketball events have been transferred to San Juan's Filoil Flying V Arena and Araneta Coliseum in Quezon City. Other collegiate sports are still held at Rizal Memorial Sports Complex. Professional basketball, which has been mostly organized by corporate teams, also used to play at the city but the Philippine Basketball Association now holds their games at Araneta Coliseum and Cuneta Astrodome at Pasay; the now-defunct Philippine Basketball League played some of their games, such as its 1995–96 Philippine Basketball League season, at Rizal Memorial Sports Complex.[306]

Manila Metrostars participated in the Metropolitan Basketball Association.[307] The Metrostars, named after the Metrostar Express – the brand name of the Metro Manila MRT-3, which does not have stations in the city – participated in its first three seasons and won the 1999 championship.[308] The Metrostars later merged with the Batangas Blades and subsequently played in Lipa, Batangas. Almost twenty years later, Manila Stars participated in the Maharlika Pilipinas Basketball League, reaching the Northern Division Finals in 2019. Both teams played in the San Andres Sports Complex. Other teams that represented Manila but did not host games in the city are the Manila Jeepney F.C. and FC Meralco Manila. The city's government acknowledged Jeepney as Manila's representative in the United Football League. Meralco Manila played in the Philippines Football League and designated Rizal Memorial Stadium as their home ground.[citation needed]

Manila's rugby league team Manila Storm trains at Rizal Park and plays matches at Southern Plains Field, Calamba, Laguna. Baseball was previously a widely played sport in the city but in 2022, Manila had the Philippines' only sizable baseball stadium, Rizal Memorial Baseball Stadium, which hosted games of the now-defunct Baseball Philippines; Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth were the first players to score a home run at the stadium during their tour of the country on December 2, 1934.[309] Cue sports are also popular in Manila; billiard halls are present in most barangays. The 2010 World Cup of Pool was held at Robinsons Place Manila.[310]

Rizal Memorial Track and Football Stadium hosted the first FIFA World Cup qualifier in decades when the Philippines hosted Sri Lanka in July 2011. The stadium, which was previously unfit for international matches, had been renovated before the match.[311] The stadium also hosted its first rugby test for the 2012 Asian Five Nations Division I tournaments.[312]

Festivals and holidays

Manila celebrates civic and national holidays. Because most of the city's residents are Roman Catholic,[313][314] most of the festivals are religious in nature. Araw ng Maynila, which celebrates the city's founding on June 24, 1571 [315] by the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi, was first proclaimed by the city's vice mayor Herminio A. Astorga on June 24, 1962. It has been annually commemorated under the patronage of John the Baptist, and has always been declared by the national government as a special, non-working holiday through presidential proclamations. Each of the city's 896 barangays also have their own festivities, which are guided by their own patron saints.[citation needed]