Potency and safety analysis of hemp-derived delta-9 products: The hemp vs. cannabis demarcation problem

Contents

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Baltic Sea |

| Coordinates | 57°30′N 18°30′E / 57.500°N 18.500°E |

| Archipelago | Slite archipelago |

| Total islands | 14 large + a number of smaller islands |

| Major islands | Gotland, Fårö, Gotska Sandön, Stora Karlsö, Lilla Karlsö, Furillen |

| Area | 3,183.7 km2 (1,229.2 sq mi) |

| Length | 125 km (77.7 mi) |

| Width | 52 km (32.3 mi) |

| Coastline | 800 km (500 mi) (including Fårö) |

| Highest elevation | 82 m (269 ft) |

| Highest point | Lojsta hed |

| Administration | |

| County | Gotland County |

| Municipality | Region Gotland |

| Largest settlement | Visby (pop. 23,600[1]) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 61,029[2][3] (2023) |

| Pop. density | 18.4/km2 (47.7/sq mi) |

| Official name | Gotland, east coast |

| Designated | 5 December 1974 |

| Reference no. | 21[4] |

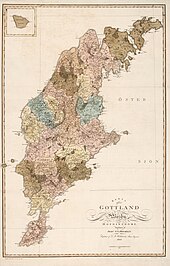

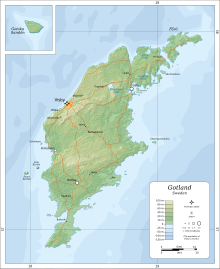

Gotland (/ˈɡɒtlənd/, Swedish: [ˈɡɔ̌tːland] ;[5] Gutland in Gutnish),[6] also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (/ˈɡɒθlənd/),[7] is Sweden's largest island.[8][9][10][11] It is also a province/county (Swedish län), municipality, and diocese. The province includes the islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to the north, as well as the Karlsö Islands (Lilla and Stora) to the west. The population is 61,023 (2024)[12] of which about 23,600 live in Visby, the main town.[1] Outside Visby, there are minor settlements and a mainly rural population. The island of Gotland and the other areas of the province of Gotland make up less than one percent of Sweden's total land area. The county formed by the archipelago is the second smallest by area and is the least populated in Sweden. In spite of the small size due to its narrow width, the driving distance between the furthermost points of the populated islands is about 170 kilometres (110 mi).[13]

Gotland is a fully integrated part of Sweden with no particular autonomy, unlike several other offshore island groups in Europe. Historically, there was a linguistic difference between the archipelago and the mainland with Gutnish being the native language. In recent centuries, Swedish took over almost entirely and the island is virtually monolingually Swedish in modern times. The archipelago is a very popular domestic tourist destination for mainland Swedes, with the population rising to very high numbers during summers. Some of the reasons are the sunny climate and the extensive shoreline bordering mild waters. During summer, Visby hosts the political event Almedalen Week, followed by the Medieval Week, further boosting visitor numbers. In winter, Gotland usually remains surrounded by ice-free water and has mild weather.

Gotland has been inhabited since approximately 7200 BC.[14] The island's main sources of income are agriculture, food processing, tourism, information technology services, design, and some heavy industry such as concrete production from locally mined limestone.[15] From a military standpoint, it occupies a strategic location at the center of the Baltic Sea.

Etymology

The name of Gotland is closely related to that of the Geats and Goths.[16]

History

Prehistoric time to Viking Age

The island was the home of the Gutes, and sites such as the Ajvide Settlement show that it has been occupied since prehistory.[17] A DNA study conducted on the 5,000-year-old skeletal remains of three Middle Neolithic seal hunters from Gotland showed that they were related to modern-day Finns, while a farmer from Gökhem parish in Västergötland on the mainland was found to be more closely related to modern-day Mediterraneans. This is consistent with the spread of agricultural peoples from the Middle East at about that time.[18]

Gutasaga contains legends of how the island was settled by Þieluar and populated by his descendants. It also tells that a third of the population had to emigrate and settle in southern Europe, a tradition associated with the migration of the Goths, whose name has the same origin as Gutes, the native name of the people of the island. It later tells that the Gutes voluntarily submitted to the king of Sweden and asserts that the submission was based on mutual agreement, and notes the duties and obligations of the Swedish King and Bishop in relationship to Gotland.[19] According to some historians, it is therefore an effort not only to write down the history of Gotland, but also to assert Gotland's independence from Sweden.[20]

It gives Awair Strabain as the name of the man who arranged the mutually beneficial agreement with the king of Sweden; the event would have taken place before the end of the ninth century, when Wulfstan of Hedeby reported that the island was subject to the Swedes:

Then, after the land of the Burgundians, we had on our left the lands that have been called from the earliest times Blekingey, and Meore, and Eowland, and Gotland, all which territory is subject to the Sweons; and Weonodland was all the way on our right, as far as Weissel-mouth.[21]

The number of Arab dirhams discovered on the island of Gotland alone is astoundingly high. In the various hoards located around the island, there are more of these silver coins than at any other site in Western Eurasia. The total sum is almost as great as the number that has been unearthed in the entire Muslim world.[22] These coins moved north through trade between Rus merchants and the Abbasid Caliphate, along the Silver-Fur Road, and the money made by Scandinavian merchants would help northern Europe, especially Viking Scandinavia and the Carolingian Empire, as major commercial centers for the next several centuries.[23]

The Berezan' Runestone, discovered in 1905 in Ukraine, was made by a Varangian (Viking) trader named Grani in memory of his business partner Karl. It is assumed that they were from Gotland.[24]

Notable archaeological findings

The Mästermyr chest, an important artefact from the Viking Age, was found in Gotland.[25][26]

On 16 July 1999, the world's largest Viking silver treasure, the Spillings Hoard, was found in a field at Spillings farm northwest of Slite.[27] The silver treasure was divided into two parts weighing a total of 67 kg (148 lb) (27 kg (60 lb) and 40 kg (88 lb)) and consisted mostly of coins, about 14,000, from foreign countries, mostly Islamic.[28] It also contained about 20 kg (44 lb) of bronze objects along with numerous everyday objects such as nails, glass beads, parts of tools, pottery, iron bands and clasps. The treasure was found by using a metal detector, and the finders fee, given to the farmer who owned the land, was over 2 million kronor (about US$308,000).[29] The treasure was found almost by accident while filming a news report for TV4 about illegal treasure hunting on Gotland.[30]

Middle Ages

Early on, Gotland became a commercial center, with the town of Visby the most important Hanseatic city in the Baltic Sea.[31] In late medieval times, the island had twenty district courts (tings), each represented by its elected judge at the island-ting, called landsting. New laws were decided at the landsting, which also took other decisions regarding the island as a whole.[32]

The city of Visby and rest of the island were governed separately, and a civil war caused by conflicts between the German merchants in Visby and the peasants they traded with in the countryside had to be put down by King Magnus III of Sweden in 1288.[33] In 1361, Valdemar Atterdag of Denmark invaded the island.[34] About 1,500 Gotlandic farmers were killed by the Danish invaders after massing for the Battle of Mästerby.[35] The Victual Brothers occupied the island in 1394 to set up a stronghold as a headquarters of their own in Visby. At last, Gotland became a fief of the Teutonic Knights, awarded to them on the condition that they expel the piratical Victual Brothers from their fortified sanctuary.[32] An invading army of Teutonic Knights conquered the island in 1398, destroying Visby and driving the Victual Brothers from Gotland. In 1409, Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen of the Teutonic Knights guaranteed peace with the Kalmar Union of Scandinavia by selling the island of Gotland to Queen Margaret of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[32]

The authority of the landsting was successively eroded after the island was occupied by the Teutonic Order, then sold to Eric of Pomerania and after 1449 ruled by Danish governors.[32] In late medieval times, the ting consisted of twelve representatives for the farmers, free-holders or tenants.[citation needed]

Early modern period

Since the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, the island has remained under Swedish rule.[32][36]

On 19 September 1806, Gustav IV Adolf offered the sovereignty of Gotland to the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, who had been expelled from Malta in 1798, but the Order rejected the offer since it would have meant renouncing their claim to Malta. The Order never regained its territory, and eventually it reestablished itself in Rome as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[37]

On 22 April 1808, during the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, a Russian army landed on the southeastern shores of Gotland near Grötlingbo. Under command of Nikolai Andreevich Bodisko 1,800 Russians took the city of Visby without any combat or engagement, and occupied the island. A Swedish naval force rescue expedition was sent from Karlskrona under the command of admiral Rudolf Cederström with 2,000 men; the island was liberated and the Russians capitulated. Russian forces left the island on 18 May 1808.

Administration

The traditional provinces of Sweden serve no administrative or political purposes today, but are historical and cultural entities. In the case of Gotland, however, due to its insular position, the administrative county (län), Gotland County, and the municipality (kommun), Region Gotland, both cover the same territory as the province. Furthermore, the diocese of Visby is also congruent with the province.[38][39][40] Gotland is traditionally divided into 92 sockens.[1] On 1 January 2016, they were all reconstituted into Districts, administrative areas with the same borders as the former sockens.[41]

Heraldry

Gotland was granted its arms in about 1560.[42] The coat of arms is represented with a ducal coronet. Blazon: "Azure a ram statant Argent armed Or holding on a cross-staff of the same a banner Gules bordered and with five tails of the third." The county was granted the same coat of arms in 1936. The municipality, created in 1971, uses the same picture, but with other tinctures.

Geography

Gotland is Sweden's largest island, and it is the largest island fully encompassed by the Baltic Sea (with Denmark's Zealand at the Baltic's edge).[8][9][10][11] With its total area of 3,183.7 km2 (1,229.2 sq mi) the island of Gotland and the other areas of the province of Gotland make up 0.8% of Sweden's total land area.[43] The province includes the small islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to the north, as well as the Karlsö Islands, (Lilla and Stora) to the west, which are even smaller. The island of Gotland has an area of 2,994 km2 (1,156 sq mi), whereas the province has 3,183.7 km2 (1,229.2 sq mi) [3,151 km2 (1,217 sq mi) of land excluding the lakes and rivers].[44] The population is 61,001 as of December 2021.[2] As of 2016, approximately 23,600 people (about 40% of residents) lived in Visby, which is the seat of the municipality and the capital of the county.[1]

Gotland is located about 90 km (56 mi) east of the Swedish mainland and about 130 km (81 mi) from the Baltic states, Latvia being the nearest. Gotland is the name of the main island, but the adjacent islands are generally considered part of Gotland and the Gotlandic culture:

- Furillen

- Fårö

- Gotska Sandön, a National park of Sweden

- The Karlsö Islands (Stora Karlsö and Lilla Karlsö)

- Laus holmar

- Ytterholmen

- Östergarnsholm

There are several shallow lakes located near the shores of the island. The biggest is Lake Bästeträsk, located near Fleringe in the northern part of Gotland. The Hoburg Shoal bird reserve is situated on the southern tip of the island.[45] The highest point of the island is Lojsta Hed which stands 82 m (269 ft) above sea level. The average height of the island is 29 meters.[46]

Settlements besides Visby include:

Of these, Hemse is the largest settlement in southern Gotland and along with Roma the two largest inland villages. Burgsvik is the southernmost locality and Fårösund the northernmost. The island of Fårö is permanently settled, but with only a few hundred year-round residents and lacks a permanent fixed link to the main island. Residents are depending on an around the clock, free of charge, car ferry for transportation over a strait roughly 1.3 km (0.81 mi) wide, taking about eight minutes.[47][48] Fårö may get connected to the main island with a bridge in the future, but the project has had plenty of delays related to funding.[49][50] At the closest point, the two islands are separated by less than 500 metres (1,600 ft), although that is at a distance from road connections.

Slite is the largest settlement on Gotland's sparsely populated east coast. The eastern coast of Gotland, including the adjacent marine waters and islets, has been designated an 150,000 ha Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports a suite of waterfowl, waders and terns.[51]

Climate

Gotland has a semi-continental variety of a marine climate (Cfb). This results in larger seasonal differences than typical of marine climates in spite of it being surrounded by the Baltic Sea for large distances in all directions. This is due to strong continental winds travelling over the sea from surrounding great landmasses. Seasonal temperature variation is smaller in more isolated places on the island such as Hoburgen or Östergarnsholm, having warmer autumn and winter, but are cooler during spring and summer days. Seasonal lag being exceptionally strong in the weather station Östergarnsholm. As an example, December is warmer than March with temperature lows being similar to April. August is typically the warmest month, an unusual occurrence in Swedish sites. In capital Visby, July and August temperatures tend to be quite even.

Since winters usually remain just above freezing and brackish water remaining liquid longer than freshwater, the sea remains ice-free all year round, except during rare extreme cold waves. The last time the whole passage from the mainland to Gotland froze was in 1987 when icebreakers were used to maintain passenger and goods traffic to the island.[52]

| Climate data for Visby Airport (2002–2020 averages, extremes since 1901) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.8 (35.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

11.3 (52.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.9 (46.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.9 (37.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

4.6 (40.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −12.7 (9.1) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.0 (−13.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46.5 (1.83) |

32.0 (1.26) |

27.9 (1.10) |

20.2 (0.80) |

28.2 (1.11) |

39.8 (1.57) |

64.8 (2.55) |

58.6 (2.31) |

40.1 (1.58) |

57.4 (2.26) |

60.9 (2.40) |

57.8 (2.28) |

534.2 (21.05) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 15 (5.9) |

13 (5.1) |

8 (3.1) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (2.0) |

7 (2.8) |

21 (8.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37 | 70 | 167 | 261 | 322 | 331 | 313 | 265 | 200 | 103 | 42 | 31 | 2,142 |

| Source 1: [53] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [54] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Visby | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 2.9 |

2.3 |

1.8 |

3.4 |

7.7 |

14.1 |

18.1 |

18.6 |

16.0 |

11.7 |

7.8 |

5.3 |

9.2 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 7.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 12.4 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[55] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Fårösund (2002–2020 averages, extremes since 1995) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.1 (86.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

13.7 (56.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

11.0 (51.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

8.6 (47.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.0 (42.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.6 (12.9) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29.7 (1.17) |

20.8 (0.82) |

21.7 (0.85) |

19.4 (0.76) |

26.3 (1.04) |

39.4 (1.55) |

53.7 (2.11) |

57.0 (2.24) |

38.1 (1.50) |

52.6 (2.07) |

49.6 (1.95) |

39.8 (1.57) |

448.1 (17.63) |

| Source 1: SMHI Open Data (temperature)[56] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SMHI Open Data (precipitation)[57] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Hemse (2002–2020 averages, extremes since 1945) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

33.7 (92.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

11.9 (53.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.1 (48.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −13.6 (7.5) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.8 (−12.6) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−22.6 (−8.7) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.6 (2.19) |

40.2 (1.58) |

34.2 (1.35) |

24.5 (0.96) |

25.7 (1.01) |

40.6 (1.60) |

72.2 (2.84) |

70.8 (2.79) |

48.2 (1.90) |

61.8 (2.43) |

68.4 (2.69) |

66.6 (2.62) |

608.8 (23.96) |

| Source 1: SMHI [58] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: SMHI [59] | |||||||||||||

Geology

Gotland is made up of a sequence of sedimentary rocks of a Silurian age, dipping to the south-east. The main Silurian succession of limestones and shales comprises thirteen units spanning 200 to 500 m (660 to 1,640 ft) of stratigraphic thickness, being thickest in the south, and overlies a 75 to 125 m (246 to 410 ft) thick Ordovician sequence.[60]

It was deposited in a shallow, hot, and salty sea on the edge of an equatorial continent.[61] The water depth never exceeded 175 to 200 m (574 to 656 ft),[62] and became shallower over time as bioherm detritus and terrestrial sediments filled the basin. Reef growth started in the Llandovery Epoch, when the sea was 50 to 100 m (160 to 330 ft), and reefs continued to dominate the sedimentary record.[60] Some sandstones are present in the youngest rocks towards the south of the island, which represent sand bars deposited very close to the shoreline.[63]

The lime rocks have been weathered into characteristic karstic rock formations known as rauks. Fossils, mainly of crinoids, rugose corals and brachiopods, are abundant throughout the island; palæo-sea-stacks are preserved in places.[64]

Economy

The island's main sources of income are agriculture along with food processing, tourism, IT solutions, design and some heavy industry such as concrete production from locally mined limestone. Most of Gotland's economy is based on small scale production.[65] In 2012, there were over 7,500 registered companies on Gotland.[66] 1,500 of these had more than one employee.[15] Gotland has the world's northernmost established vineyard and winery, located in Hablingbo.[67][68]

| Gotlands largest employers in 2015[69] | |

|---|---|

| Company | Employees |

| Region Gotland | 5700 |

| AB Svenska Spel ("Swedish Games") | 360 |

| PayEx ("Payment solutions") | 310 |

| Destination Gotland (Ferries and accommodations) | 300 |

| Försäkringskassan ("Swedish Social Insurance Agency") | 280 |

| Samhall AB (Providing employment for disabled persons) | 260 |

| Cementa (Concrete industry) | 240 |

| Uppsala University Campus Gotland ("Gotland university") | 180 |

| Swedish Police Authority ("Police") | 180 |

| Gotlands Energientreprenad AB (Electrical company) | 150 |

| COOP Gotland ek för. (Swedish consumers co-operative) | 150 |

| ICA MAXI/Brukets Livs AB (Hypermarket) | 130 |

| Gotlands Slagteri AB (Food company) | 130 |

| Länsstyrelsen i Gotlands län (County administrative board) | 120 |

| Gotlands Hemstjänster AB (Personal assistance) | 120 |

| Skatteverket ("Swedish Tax Agency") | 110 |

| Riksantikvarieämbetet ("Swedish National Heritage Board") | 110 |

| Wisby Assistans AB (Personal assistance) | 110 |

| Gotlands Bilfrakt AB (Freight company) | 100 |

| PostNord Sverige ("Swedish Post") | 90 |

Military

Gotland occupies a strategic location in the Baltic sea from a defence viewpoint. In March 2015, the Swedish government decided to begin reestablishing a permanent military presence on Gotland, starting with an initial 150 troop garrison,[70] consisting primarily of elements from the Swedish Army. It has been reported that the bulk of this initial garrison will make up a new motorised rifle battalion,[71] alternatively referred to in other reports as a "modular-structured rapid response Army battalion". A later report claimed that plans were at an advanced stage for a support helicopter squadron and an Air Force "fast response Gripen jet squadron" to also be based on the island to support the new garrison and further reinforce the defences.[72] Prior to the disbandment of the original garrison, there had been a continuous Swedish military presence on Gotland in one form or another, for nearly 200 years.[73]

After the standing down of the original garrison, a battalion of the Swedish Home Guard is based on Gotland for emergencies as part of the Eastern Military Region (MR E). The unit, 32:a Gotlandsbataljonen (the 32nd Gotland battalion), acts as a reserve component of the Swedish Amphibious Corps.[74] Among the residual war reserve stocks reported to be still in storage on Gotland in March 2015, were 14 tanks[75] (Stridsvagn 122s) at the Tofta skjutfält (the Tofta firing range),[76][77] but without any crews or dedicated maintenance personnel assigned to them.[78]

Gotland currently has no local air defence capability.[79] Despite its importance as a naval base in the past,[80] as of 2004, there are no naval units based on Gotland.[79] The Tofta firing range itself (also known as the Tofta Tank firing range), is a military training ground which is located 8 km (5.0 mi) south of Visby. Another less common name for the range is the Toftasjön firing range. Tracing its origins back to 1898, as of 2008 the range extended over 2,700 acres (11 km2). It was a major training and storage facility for the Gotland garrison during its existence, and was still occasionally used for training by various elements of the Armed Forces since the garrison was shut down in 2005. However, from the second half of 2014 onwards, there has been a marked increase in the use of the range, especially by armored units (mostly company sized),[77] as tensions in Northeastern Europe have escalated. At least one of the buildings on the range, the former tank repair shop, is currently owned by a private company (Peab), with the military renting back the top floor for its own use.[78] When not used by the military, a number of cultural and sports events have been held at the range, one of the most notable being the Gotland Grand National, the world's largest enduro race, from 1984 to 2023.[81][82] As of 2018, Gotland has received a lot more attention military-wise and has seen a much larger spending on the military. As of 2018, the Gotland Regiment has been re-raised and is the first time since World War II that a new regiment has been established in Sweden.

Tourism

The first modern day tourists came to Gotland during the 19th century and were known as "bathers".[83] Gotland became very popular with socialites at the time through Princess Eugenie who lived in Västerhejde, in the west part of the island from the 1860s.[84][85]

When a new law ensuring two weeks vacation for all employees in Sweden was passed in 1938, camping became a popular pastime among the Swedes, and in 1955, Gotland was visited by 80,000 people.[85] In the 1970s mostly young people were attracted to Gotland. Since 2010 the island has become a more versatile vacation spot visited by people from all over the world, in all manner of ways.[85]

In 2001, it was the fifth largest tourist destination in Sweden based on the total number of guest nights.[86] Gotland is usually the part of Sweden which receives the most hours of sunlight during a year with Visby statistically the location with the most sunshine in Sweden.[87] In 2007 approximately 750,000 people visited Gotland.[15]

In 1996, for the first time, ferries between Gotland and mainland Sweden carried more than 1 million passengers in a year. In 2007, the number of passengers exceeded 1.5 million.[88] In 2012, the ferries had 1,590,271 passengers and the airlines 327,255 passengers.[89] Even during the COVID-19 pandemic tourism did not change much as Swedes chose to visit the island instead of travelling abroad.[90]

| Number of tourists from top five countries in 2012[91] | |

|---|---|

| 31,664[92] | |

| 16,350[92] | |

| 13,620[92] | |

| 12,743[92] | |

| 2,983[92] | |

| Based on the number of commercial guest nights at hotels, cabins, hostels, camping and private lodgings. | |

Cruise ships and new pier

The main port of call on Gotland is Visby. The city is visited by a number of cruise ships every year.[93][94] About 40 cruise lines frequent the Baltic sea with Visby as one of their destinations.[95] In 2005, 147 ships docked at Visby, in 2010 the number was 69.[96] In 2014, 62 ships are scheduled to visit Visby.[97] The decrease in visiting ships is due to the fact that the modern cruise ships are too large to enter Visby harbor.[96] Ships must anchor a fair distance from shore whereupon passengers are shuttled to shore in small boats, which is not possible during bad weather.[98] In 2007, the first proposition for building a new pier at Visby harbor, large enough to serve the modern cruise ships, was made.[99] In 2011, the matter of the new pier was discussed in the Riksdag[100] and in 2012 research and planning for the pier began.[96] In January 2014, a letter of intent for building a new cruise pier in Visby harbor was signed by Region Gotland and Copenhagen Malmö Port (CMP). The pier was finished in 2018. The estimated cost is 250 million crowns (about US$38.52 million).[101][102]

Culture

A number of stones with grooves exist on Gotland. Archaeologists interpret these grooves as traces of an unknown industrial process in the High Middle Ages. There are approximately 3,700 grinding grooves, of which about 750 occur in the solid limestone outcrop and the rest in other rock formations. The latter often consist of hard rocks such as granite or gneiss, but also soft rocks such as sandstone occur.[103] Grinding grooves are also found in Skåne, in southern Sweden and in Finland. Astronomer Göran Henriksson dates a number of these grinding grooves to the Stone Age, from c. 3300 BC to c. 2000 BC, based on astronomical alignments,[104] although his methodology has been heavily criticized.[105]

The Medieval town of Visby has been entered as a site of the UNESCO World heritage programme. An impressive feature of Visby is the fortress wall that surrounds the old city, dating from the 13th century.[106]

Many of the residents still speak Gutnish (Gutamål), the autochthonous language on the islands. But most of them now speak Gotlandic (Swedish: gotländska), a Gutnish-influenced Swedish dialect.[107] In the 13th century, a work containing the laws of the island, called "the Gotlandic law" (Gutalagen), was published in Old Gutnish, as well as the Gutasaga.[108]

Gotland is noted for its 94 Medieval churches,[109] most of which are restored and in active use. These churches exhibit two major styles of architecture: Romanesque and Gothic. The older churches were constructed in the Romanesque style from 1150 to 1250. The newer churches were constructed in the Gothic architectural style that prevailed from about 1250–1400. The oldest painting inside one of the churches on Gotland stretches as far back in time as the 12th century.[110]

Traditional games of skill like Kubb, Pärk, and Varpa are played on Gotland. They are part of what has become called "Gutniska Lekar", and are performed preferably on the Midsummer's Eve celebration on the island, but also throughout the summer months. The games have widespread renown; some of them are played by people as far away as in the United States.[111]

The knotwork design subsequently named the "Valknut" has the most attested historic instances on picture stones in Gotland, which include being on both the Stora Hammars I and the Tängelgårda stones.[112] Gotland also has a rich heritage of folklore, including myths about the bysen, Di sma undar jordi, Hoburgsgubben and the Martebo lights.[113][114]

Gotland gives its name to the traditional farmhouse ale Gotlandsdricka, a turbid beer with much in common with Finnish sahti, and related beers from the Baltic states.[115]

Notable people

There are a number of notable people born or living on Gotland, or in other major ways associated with the island.[116]

Sport

Events

- Gotland competes in the biennial Island Games, which it hosted in 1999 and 2017.[117][118]

- Round Gotland Race-sailing event ("ÅF Offshore Race") starting at Stockholm, around the island of Gotland and back.[119]

- Gotland Grand National (GGN) is an annual enduro race on Gotland. GGN is a part of the Swedish enduroklassikern (enduro classics, Ränneslättsloppet, Stångebroslaget and Gotland Grand National). GNN is the world's largest enduro race.[120][121]

- Stånga Games are annual games for Gotlandic sports. The games are held during five days each summer in Stånga. The games are unofficially called "the Gotland Olympic Games". Some of the sports at the Stånga Games are pärk, varpa and caber toss.[111]

Organizations

In 2012, there were 171 registered sports organizations on Gotland.[122]

Gotland has two senior women's sport teams playing in the first tiers: basketball team Visby Ladies Basket Club (in Basketligan dam) and floorball team Endre IF (in the Swedish Super League).[123][124] Visby Ladies won the Swedish Championship in 2005.[125]

Football in the province is administered by Gotlands Fotbollförbund. The leading football club is FC Gute, playing in the fourth-tier league Division 2 as of 2014.[126]

Visby/Roma HK is a hockey club located in Visby, currently playing in group East of Hockeyettan.[127]

In popular culture

The Long Ships, or Red Orm (original title: Röde Orm), a best-selling Swedish novel written by Frans G. Bengtsson, contains a vivid description of Gotland in the Viking Age. A section of the book is devoted to a Viking ship setting out to Russia, stopping on its way at Gotland and engaging a pilot from the island who plays an important part in their voyage. Gotlanders of the Viking era are depicted as city people, more sophisticated and cosmopolitan than other Scandinavians of their time, and proud of their knowledge and skills.

Naomi Mitchison, in her autobiographic book "You may well ask", relates an experience during a walking tour in Sweden: "Over in Gotland I walked again, further than I would have if I had realized that the milestones were in old Swedish miles, so that my disappointing three-mile walk along the cold sea edge under the strange ancient fortifications was really fifteen English miles [24 km]".[128]

The crime novels of Mari Jungstedt, featuring Detective Superintendent Anders Knutas, are set on Gotland.

In the Battlefield Vietnam video game modification Invasion Gotland, the Soviet Union invades Gotland in 1977.

For the 1989 Studio Ghibli film, Kiki's Delivery Service, by Hayao Miyazaki, he and other illustrators spent time in Gotland in preparation for animation.

Astronomy

A number of asteroids in the main-belt are named after places on Gotland or Gotlanders, such as 10795 Babben, 3250 Martebo and 7545 Smaklösa. Most of them have been named by Swedish astronomer Claes-Ingvar Lagerkvist, a summer resident on Gotland. All the Gotlandic names are vividly described in NASA's JPL Small-Body Database in connection to each asteroid.[129][130]

See also

- Cold War II

- Danes

- Danes (Germanic tribe)

- Geats

- Germanic peoples

- Gothic alphabet

- Gothic language

- Gotland Museum

- Gotland National Conscription

- HVDC Gotland

- Kvenland

- List of church ruins on Gotland

- List of churches on Gotland

- Norsemen

- Old Norse

- Proto-Norse language

- Scandza

- Sweden during World War II

- Sweden proper

- Vavle

References

- ^ a b c d "Gotland i siffror, pdf". www.gotland.se. Region Gotland. pp. 65–67. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Statistics Sweden (as of December 31, 2021)". Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Folkmängd 31 december; ålder". Statistikdatabasen. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Gotland, east coast". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ http://sok.saol.se/pages/P296_M.jpg Archived 13 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine Svenska Akademiens ordlista, 6 February 2013

- ^ "Namnet Gotland" [The name Gotland]. www.guteinfo.com. Guteinfo. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Gotland definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b Renate Platzöder; Philomène A. Verlaan (1996). The Baltic Sea: new developments in national policies and international cooperation, Volume 1. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-0357-0.

- ^ a b Sailing Directions, Baltic Sea. ProStar Publications. 1978. ISBN 978-1-57785-759-4.

- ^ a b Knowles, Heather (2010). Passport Series: Western Europe. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-1-4291-2255-9. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Zealand". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Folkmängd och befolkningsförändringar - Kvartal 1, 2024". Statistikmyndigheten SCB (in Swedish). Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ "Distance Hoburg, Gotlands-Kommun, SWE → 57.96006234498054,19.34967041015625". Distance.to. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ Larsson, Per. "Oväntade fynd i grotta på Stora Karlsö – Stockholms universitet". www.su.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "Fakta om Gotland". Website. Länsstyrelsen Gotland. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Strid, Jan Paul (January 2010). "The Origin of the Goths from a Topolinguistic Perspective". North-Western European Language Evolution. 58 (59). John Benjamins Publishing Company: 443–452. doi:10.1075/nowele.58-59.16str.

- ^ Outram, A. K. 2006. Distinguishing bone fat exploitation from other taphonomic processes: what caused the high level of bone fragmentation at the Middle Neolithic site of Ajvide, Gotland? Archived 20 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 32–43. In Mulville, J and Outram, A (eds). The Zooarchaeology of Milk and Fats. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- ^ Nicholls, Henry (26 April 2012). "Ancient Swedish farmer came from the Mediterranean". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10541. S2CID 131363264. Archived from the original on 22 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022 – via www.nature.com.

- ^ "Gutagatan, based on Gannholm's 1992 edition". www.runeberg.org. Project Runeberg. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Enderborg, Bernt. "Staten Gotland". www.guteinfo.com. Guteinfo. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Discovery of Muscovy by Richard Hakluyt – Project Gutenberg. 1 May 2003. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2010 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Johansson, Marcus; Jonsson, Kenneth (1997). "Islamiska mynt" (PDF). www.archeology.su.se. Numismatiska forskningsgruppen, Stockholms universitet. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Vikingarnas historia". www.rosala-viking-centre.com. Rosala Viking center. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Jansson, Sven B. F. (1962). The runes of Sweden. Stockholm: Norstedt. pp. 3–4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Åhlin, Christer. "Verktygskista från Mästermyr". www.historiska.se. Historiska Museet. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ Hellner, Brynolf. "Tidigare publikationer om Mästermyrfyndet". wwwhistoricallocks.com. Historical locks. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ "Spillingsskatten". www.historiska.se. Historiska Museet. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Unikt mynt hittat i Spillingsskatten". www.hallekis.com. Hallekiskuriren. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Ann-Marie Pettersson, ed. (2008). Spillingsskatten: Gotland i vikingatidens världshandel. Visby: Länsmuseet på Gotland. ISBN 978-91-88036-69-8. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Ström, Jonas. "Världens största vikingatida silverskatt". www.historiska.se. Historiska museet. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Yrwing, Hugo (1986). Visby – hansestad på Gotland (in Swedish). Stockholm: Gidlund. ISBN 91-7844-055-6. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Martinsson, Örjan. "Gotland". www.tacitus.nu. TACITUS.NU. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Sundberg, Ulf (1997). Svenska freder och stillestånd 1249–1814 (in Swedish) (1 ed.). Hargshamn: Arte. ISBN 91-89080-01-7. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Westholm, Gun (2007). Visby 1361: Invasionen (in Swedish). Stockholm: Prisma. ISBN 978-91-518-4568-5. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Lingström, Allan. "Invasionen-fakta och teorier". www.masterby1361.se. Mästerby1361. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Englund, Peter (2003). Ofredsår (in Swedish). Stockholm: Atlantis. pp. 368 and 394. ISBN 91-7486-349-5.

- ^ Stair Sainty, Guy (2000). "From the loss of Malta to the modern era". ChivalricOrders.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012.

- ^ "Välkommen till Region Gotlands hemsida!". www.gotland.se. Region Gotland. Archived from the original on 13 August 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Länsstyrelsen Gotlands län". www.lansstyrelsen.se. Länsstyrelsen Gotlands län. Archived from the original on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Visby Stift". www.svenskakyrkan.se. Sveska Kyrkan. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Förordning om district" [Regulation of districts] (PDF). Ministry of Finance. 17 June 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Clara Nevéus, Bror jacques de Wærn: Ny svensk vapenbok, 1992

- ^ "Gotland i siffror 2013 ("Gotland in numbers 2013")". pdf. Region Gotland. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Statistisk årsbok för Sverige 2009". Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "MP Atlas; Hoburgs Bank Special Protection Areas (Birds Directive)". Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "Island Gotland". Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Tidtabell Fårösundsleden – Trafikverket" (PDF) (in Swedish). Trafikverket (Swedish Transportation Agency). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Fårösundsleden" (in Swedish). Trafikverket (Swedish Transport Agency). Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Widegren, Patrik (12 December 2019). "Fortsatta diskussioner om bro till Fårö". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). SVT East. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Zetterdahl, Christian S (14 January 2021). "Politikerna gör tummen ner för bro till Fårö". SVT Nyheter. SVT East. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Coastal area of Eastern Gotland". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2024. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ "Isvintern 1986-1987.pdf" (PDF) (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Monthly & Yearly Statistics" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Ladda ner meteorologiska observationer – Visby D" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Dublin, Ireland – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Ladda ner meteorologiska observationer – Fårösund Ar A Statistics" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Ladda ner meteorologiska observationer – Fårösund Ar A" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Ladda ner meteorologiska observationer – Hemse" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "Ladda ner meteorologiska observationer – Hemse" (in Swedish). SMHI. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b Laufeld, S. (1974). Silurian Chitinozoa from Gotland. Fossils and Strata. Universitetsforlaget.

- ^ Creer 1973

- ^ Jane Gray; S. Laufield; Arthur J. Boucot (1974), "Silurian trilete spores and spore tetrads from Gotland: their implications for land plant evolution", Science, 185 (4147): 260–263, Bibcode:1974Sci...185..260G, doi:10.1126/science.185.4147.260, PMID 17812053, S2CID 22967281

- ^ Long, D.G.F. (1993). "The Burgsvik beds, an Upper Silurian storm generated sand ridge complex in southern Gotland". Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar. 115 (4): 299–309. doi:10.1080/11035899309453917. ISSN 0016-786X.

- ^ Laufeld, Sven; Martinsson, Anders (22–28 August 1981). "Reefs and ultrashallow environments. Guidebook to the field excursions in the Silurian of Gotland". Project Ecostratigraphy Plenary Meeting.

- ^ Gibson, Mimmi. "Gotländskt näringsliv". Website. Länsstyrelsen Gotland. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Gotland i siffror 2013 ("Gotland in numbers 2013")". pdf. Region Gotland. p. 18. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Därför säljs Gute vingård". www.helagotland.se. Gotlands Tidningar. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Pappinen, Lauri. "English information". www.gutevingard.se. Gute Vingård AB. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "GOTLAND I SIFFROR" [GOTLAND IN NUMBERS] (in Swedish). Region Gotland. 2016. p. 19. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

Number of permanent employees stationed on the island

- ^ Milne, Richard (12 March 2015). "Sweden sends troops to Baltic island amid Russia tensions". Financial Times. ft.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Gotland får permanent militär styrka Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine helagotland.se (in Swedish)

- ^ O'Dwyer, Gerard (20 March 2015). "Sweden Invests in Naval Capacity, Baltic Sea Ops". DefenseNews. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Olsson, Kjell. "Militärbefälet på Gotland" [Military command on Gotland]. www.gotlandsforsvarshistoria.se (in Swedish). Gotlands Militärhistoria och Gotlands Trupper. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Gotlandsbataljonen". www.forsvarsmakten.se. Swedish Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Braw, Elisabeth. "Gotland Island, the Baltic Sea's Weak Link". www.worldaffairsjournal.org. World Affairs. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Stridsvagnar åter på Gotland" [Tanks return to Gotland]. www.forsvarsmakten.se. Swedish Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ a b "I 19 tar över på Gotland" [In 19 takes over on Gotland]. Swedish Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ a b Kadhammar, Peter (18 February 2013). "Blir det krig får armén köpa mat på Ica Maxi" [If the war comes, the army will have to buy their food at Ica Maxi]. www.aftonbladet.se. Aftonbladet. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ a b Olsson, Kjell. "Militärbefälet på Gotland". www.tjelvar.se (in Swedish). Gotlands Militärhistoria och Gotlands Trupper. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Olsson, Kjell. "Gotlands Marindistrikt – Visbyavdelningen (Vba) – 1931–1956" [Gotland Navy District – Visby section – 1931–1956]. www.gotlandsforsvarshistoria.se (in Swedish). Gotlands Militärhistoria och Gotlands Trupper. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Gottfridsson, Thomas (November 2013). "GGN firar 30 år med rekordantal" [Record breaking number of participants celebrates 30 years of GNN]. www.helagotland.se (in Swedish). HelaGotland. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Pearson, Jon (19 September 2023). "Gotland Grand National evicted – Swedish Army call time on traditional GGN home". Enduro21. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Jonsson, Marita (1987). Vägen till kulturen på Gotland. Gotländskt arkiv, 0434-2429; 59(1987). Visby: Gotlands fornsal. ISBN 91-971048-0-9. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Ljugarn, historia". Website. Ljuvliga Ljugarn. Archived from the original on 1 June 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b c "Turisthistoria". Website. Länsstyrelsen Gotland. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Gotland populärt turistmål". Website. Sveriges Radio. 24 April 2002. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Sjögren, Helena (16 May 2013). "Solkrig pågår mellan Karlskrona och Visby". Website/Newspaper. Expressen & SMHI. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Fritz, Staffan. "Passagerare nr 1500000". Website/Newspaper. Helagotland. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Gotland i siffror 2013 ("Gotland in numbers 2013")". pdf. Region Gotland. p. 27. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Delby, Johan (4 August 2020). "Hyfsad sommar för Gotlands turism" [Acceptable summer for Gotland's tourism] (in Swedish). Dagens Samhälle. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Gotland i siffror 2013 ("Gotland in numbers 2013")". pdf. Region Gotland. p. 24. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e These numbers do not include visitors arriving by cruise ship. See section "Cruise ships".

- ^ Klint, Kerstin. "Större kryssningsfartyg till Visby". www.gotland.net. Visit Gotland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Visitors on these ships are not included in the statistics in the section above since they come to Gotland in ships owned by other shipping companies than Destination Gotland, and these visitors only disembark during the day and do not use the accommodation available on Gotland.

- ^ Stenberg, Johan (31 March 2010). "Bara 69 kryssningsfartyg till Visby". Website/Radio programme. P4 Gotland. Sveriges Radio. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Att angöra en kaj eller passera en ö, pdf". www.gotland.se. Sweco Eurofutures AB. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Wahlberg, Lars. "Cruise Calls 2014, Port of Visby, pdf". www.gotland.se. Port of Visby, Teknikförvaltningen, Hamnavdelningen, Region Gotland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Staflin, Mona; Pettersson, Mats (18 November 2013). "Kryssningskaj kan ge 130 miljoner". Newspaper/website. Gotlands Allehanda. Helagotland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Wesley, Stefan. "Planer för en kryssningskaj i Visby". www.gotland.se. Region Gotland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Engelhart, Christer. "Motion 2011/12:T416 Kryssningskaj i Visby". www.riksdagen.se. Sveriges Riksdag. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Andersson, Lars (29 January 2014). "Ny kryssningskaj i Visby". Website/Newspaper. Sjöfartstidningen. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Bringmark, Karsten (25 March 2014). "CMP förhandlar om kryssningskaj i Visby". Website/Newspaper. Skånskan. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Gibson, Olov (2013). "Gotlands slipskåror: spår av friktionsbromsar hos väderkvarnar?". Fornvännen. 108 (2): 130–133. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Henriksson, Göran (1983). "Astronomisk tolkning av slipskåror på Gotland" (PDF). Fornvännen. Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Lindström, Jonathan; Roslund, Curt (2000). "Göran Henrikssons nonsensforskning". Folkvett. Vetenskap och Folkbildning. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "Hanseatic Town of Visby". www.whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage List. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Svenska förklarad: Gutamål och gotländska | UR Play". urplay.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Olsson, Kjell. "Gutalagen på svenska". www.tjelvar.se (in Swedish). Gotlands Militärhistoria och Gotlands Trupper. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Andrén, Anders (2015). Det medeltida Gotland: En arkeologisk guidebook. Vol. 8. Svenska Historiska Media Förlag AB. ISBN 978-91-87031-31-1. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Lagerlöf, Erland; Svahnström, Gunnar (1973). Gotlands kyrkor: en vägledning (in Swedish) (2. omarb o utök. uppl. ed.). Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. ISBN 91-29-41035-5. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Stångsspelen". www.stangaspelen.com. Föreningen Gutnisk Idrott (FGI). Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Valknut, triskele, Hrungnir's hjärta". www.guteinfo.com. Guteinfo. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Saga". www.guteinfo.com. Guteinfo. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Wallin, Inga-Lill. "Marteboljuset". www.ufo.se. UFO Sverige. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ "Dricku". www.guteinfo.com. Guteinfo. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Pettersson, Mats (9 December 2011). "Berömda gotlänningar" [Notable Gotlanders]. www.gotland.net. Gotlands Media AB. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Gotland – Member profile". www.islandgames.net. INternational Island Games Association. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "The Official 2017 Island Games website". Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "ÅF Offshore Race". www.ksss.se. Royal Swedish Yacht Club. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Gotland Grand national". www.nordicsportevent.se. Nordic sport & event. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Världens största endurotävling går av stapeln". www.tv4.se. Tv 4, Sweden. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Gotland i siffror 2013 ("Gotland in numbers 2013")". pdf. Region Gotland. p. 41. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Teams in Basketligan dam". Swedish Basketball Federation. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Women's Swedish Super League". Swedish Floorball Federation. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Visby Ladies svenska mästare i basket 2005" (in Swedish). guteinfo.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ "Gotlands idrottsförbund". www.gotsport.se. Gotlands idrottsförbund. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Visby/Roma". www.eliteprospects.com/. Elite Prospects. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Naomi Mitchison, You may well ask", London, 1979, Part I, Chap 7.

- ^ Lagerkvist, Claes-Ingvar; Hahn, Gerhard (3 March 2011). "Blågula asteroider" [Blue-yellow asteroids]. www.popularastronomi.se. Populär Astronomi. Retrieved 25 June 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Joelsson, Johan (2014). "Vem döper stjärnorna?" [Who is naming the stars?]. www.spraktidningen.se. Språktidningen. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

Further reading

There are over 8,700 titles about Gotland in the National Library of Sweden online database LIBRIS. About 560 of the books are in English. See: LIBRIS.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Gotland, facts and statistics 2013, pdf, Gotland County. (in English)

- Important years in Gotland' s history GotslandsResor tourist website (in English)

- Official portal for Gotland County (in Swedish)

- Gotland administrative portal (in Swedish)

- Swedish Radio on Gotland, P4 (in Swedish)

- Portal on Gotland with detailed facts about everything on the island (in Swedish)

- Commercial portal on Gotland Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in Swedish)

- Official Gotland Tourist Association (in Swedish)

- Famous footprints – traveling on Gotland (in English)

- Portal for eastern Gotland – Östergarnslandet (in Swedish)

- Portal for eastern Gotland – Ljugarn Archived 12 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in Swedish)

- Gotland (in Interlingua)

- Interactive map of Gotland (in Swedish)

- A short video (with music) with footage of the Gotland Grand National 2007

- Gotland Grand National (GGN) webpage Archived 24 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Nordic Sport & Event)