Potency and safety analysis of hemp-derived delta-9 products: The hemp vs. cannabis demarcation problem

Contents

An antimonial cup was a small half-pint mug or cup cast in antimony popular in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. They were also known under the names "pocula emetica," "calices vomitorii," or "emetic cups", as wine that was kept in one for a 24‑hour period gained an emetic or laxative quality. The tartaric acid in the wine acted upon the metal cup and formed tartarised antimony.[1][2]

History

Roman banquets of antiquity had goblets of specially prepared antimony-doctored wine. The antimonial cup would be employed in order to facilitate repeated doses of overeating by a followup of purging.[3] The resurrection of the antimonial cup may have occurred because of the prohibition of antimony in 1566 by an Act of Parliament. As a method to circumvent the law, metal tin cups were made with antimony as one of its ingredients.[4] When wine was allowed to stand in one for approximately 24 hours the wine became impregnated with tartrate of antimony, from the action of the tartar contained in the wine upon the metal of the film of oxide formed upon its surface.[5] This resulting alcoholic drink was attractive to sick patients as a medicine by purging the body. The family antimonial cup gathered increased powers of suggestion with years of being handed down from generation to generation.[6] Antimonial cups were used in England and America from earlier part of the 17th century and well into the 18th century. The spelling at the time was "Antimonyall Cupps." The cups were common in monasteries.[6]

Antimonial cups are extremely rare as only six are known in Great Britain, all in London, two in the Netherlands (Amsterdam and Leiden), one in Basel, Switzerland, one in Italy in the former papal palace in Ariccia and another one in London believed to have belonged to Captain James Cook, the English navigator. It is in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, London. The reason he had an antimonial cup is mostly of speculation, anything from stomach problems to scurvy. The provenance shows that it was acquired on loan in 1983 from Lady Rowley, daughter of the 8th Viscount Galway, Governor General of New Zealand. The family regarded it as a pewter communion cup and had owned it for many years. Lady Rowley's ancestor, General Robert Monckton, was General James Wolfe's second in command at Quebec. Cook was involved in the St Lawrence Expedition of 1759 under the joint command of Admiral Sir Edward Saunders and General Wolfe. The antimonial cup may have been bought by the 5th Viscount Galway (William George Monckton-Arundell) between 1815 and 1830 amongst Cook relics from a sale of the effects of Rear Admiral Isaac Smith, a nephew and companion of Mrs Elizabeth Cook (widow of James Cook).[2]

Description

The 1728 Cyclopaedia by Ephraim Chambers says it was made either of glass of antimony or of antimony prepared with saltpeter. The liquid obtained from the resultant wine or liquor left in it for 24 hours was not dissoluble by the stomach. The infused liquid containing antimony would give a cathartic or emetic effect.[7]

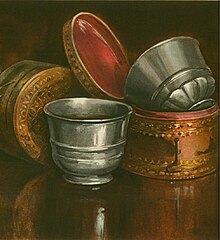

There is an antimonial cup at the Geological Museum, London, that has an inscription on the shield of the small ornamental lid that reads, Du bist ein Wunder der Natur und aller Menschen sichere Cur ("You are a wonder of nature and for all people a certain cure"). These pictured display cups may be "plate pewter" consisting of 89 percent tin and 7 percent antimony. It could, however, be "triple pewter" containing less tin and as much as 15 percent antimony.[6]

The size of those used in England and America from the 17th century were about two inches high and about two in diameter. They held about four ounces of wine. Although there were other kinds of emetics in this time period available, many households possessed an antimonial cup of their own.[8] The instructions typically were to fill the antimonial cup at 6 PM with white wine and take all the wine at 7 AM the next morning to induce vomiting. A child was instructed to take just half the amount. If it had not induced vomiting within a couple of hours, then they were to take the other half of the liquid. This method of using wine to gather a small portion of the metallic part of antimony was dependent on the acidity of the wine. If the wine was too acidic, then the concoction could become too strong for the body, resulting in poisoning or even death.[8]

See also

References

- ^ The Technologist, p. 393

- ^ a b Captain James Cook's Antimony Cup

- ^ Mauder, p. 228

- ^ "Antimony cup with leather case, Europe, 1601-1700". Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ "Antimony cup, Europe, 1501-1700". Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ a b c Thomson SC (1926). "Antimonyall Cupps: Pocula Emetica or Calices Vomitorii". Proc. R. Soc. Med. 19 (Sect Hist Med): 122.2–128. PMC 1948687. PMID 19985185.

- ^ Chambers, p. 109

- ^ a b Account of an Antimonial Cup , p. 582

Sources

- Account of an Antimonial Cup, from The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 102, Part 1, E. Cave, 1832

- Chambers, Ephraim, Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences : containing the definitions of the terms, and accounts of the things signify'd thereby, in the several arts, both liberal and mechanical, and the several sciences, human and divine : the figures, kinds, properties, productions, preparations, and uses, of things natural and artificial : the rise, progress, and state of things ecclesiastical, civil, military, and commercial : with the several systems, sects, opinions, &c : among philosophers, divines, mathematicians, physicians, antiquaries, criticks, &c : the whole intended as a course of antient and modern learning. (1728)

- Mauder, Andrew, Victorian crime, madness and sensation, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004, ISBN 0-7546-4060-4

- The Technologist, Volume 1, Kent & Co., 1861