Laboratory demand management strategies: An overview

Circassia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 7th century–1864 | |||||||||

| Motto: Псэм ипэ напэ (Adyghe) Psem ipe nape ("Honour before life") | |||||||||

Area marked Circassia | |||||||||

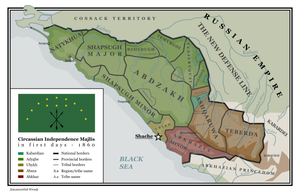

Revised administrative divisions of Circassia in 1860 according to a decree issued by the Circassian Parliament | |||||||||

| Residence of leader (Capital) |

43°35′07″N 39°43′13″E / 43.58528°N 39.72028°E | ||||||||

| Largest town | Shache (Sochi) | ||||||||

| Official languages | Circassian languages | ||||||||

| Other languages | |||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Circassian | ||||||||

| Government | Union of Regional Councils[1][2] | ||||||||

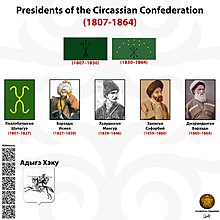

• Leader of Western Circassia c. 100s c. 400s c. 500s 668–960 c. 960s–1000s c. 1000s–1022 c. 1200s c. 1200s–1237 1237–1239 c. 1330s c. late 1300s c. 1427–1453 c. 1453-c. 1470s c. 1470s-? c. 1530s–1542 1807–1827 1827–1839 1839–1846 1849–1859 1859–1860 1861–1864 | List: Stakhemfaqu (Stachemfak) Dawiy Bakhsan Dawiqo Khazar rule Hapach Rededya Abdunkhan Tukar Tukbash Verzacht Berezok Inal the Great Belzebuk Petrezok Kansavuk Shuwpagwe Qalawebateqo Ismail Berzeg Hawduqo Mansur Muhammad Amin Sefer Bey Zanuqo Qerandiqo Berzeg | ||||||||

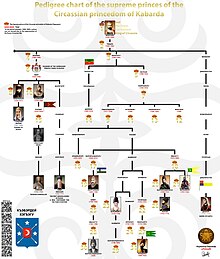

• Prince of Eastern Circassia c. 1427–1453 1453–c. 1490 c. 1490–c. 1500 c. 1500–c. 1525 c. 1525–c. 1540 c. 1540–1554 1554–1571 1571–1578 1578–1589 1589–1609 1609–1616 1616–1624 1624–1654 1654–1672 1672–1695 1695–1710 1710–1721 1721–1732 1732–1737 1737–1746 1746–1749 1749–1762 1762–1773 1773–1785 1785–1788 1788–1809 1809 1810–1822 | List: Inal the Great Tabulda Inarmas Beslan Idar Kaytuk I Temruk Shiapshuk Kambulat Kaytuk II Sholokh Kudenet Aleguko Atajuq I Misost Atajuq II Kurgoqo Atajuq III Misewestiqo Islambek Tatarkhan Qeytuqo Aslanbech Batoko Bamat Muhammad Qasey Atajuq Jankhot Misost II Bematiqwa Atajuq III Atajuq IV Jankhot II Qushuq | ||||||||

| Confederation Leaders | |||||||||

| Legislature | Lepq Zefes Parliament of Independence (1860-1864) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | c. 7th century | ||||||||

| 1763–1864 | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 1864 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 82,000 km2 (32,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• Estimate | 1,625,000 (pre-Circassian genocide)[clarification needed] 86,655 (post-Circassian genocide)[clarification needed][3][4][5][6][7] | ||||||||

| Currency | No official currency. Ottoman coins served as de facto currency | ||||||||

Circassia in 1450 during the reign of Inal the Great | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Russia Georgia [a] | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Circassians Адыгэхэр |

|---|

List of notable Circassians Circassian genocide |

| Circassian diaspora |

| Circassian tribes |

|

Surviving Destroyed or barely existing |

| Religion |

|

Religion in Circassia |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| History |

|

Show |

| Culture |

Circassia[b] (/sɜːrˈkæʃə/ sir-KASH-ə), also known as Zichia,[8][9] was a country and a historical region in Eastern Europe. It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea.[10][11] Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Circassian War (1763–1864), after which approximately 90% of the Circassian people were either exiled or massacred in the Circassian genocide.[12][13][14][15][16]

In the medieval era, Circassia was nominally ruled by an elected Grand Prince, but individual principalities and tribes were autonomous. In the 18th–19th centuries, a central government began to form. The Circassians also dominated the northern end of the Kuban River, but were eventually pushed back to the south of the Kuban after suffering losses to military raids conducted by the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde, and the Crimean Khanate. Their reduced borders then stretched from the Taman Peninsula to North Ossetia. Circassian lords subjugated and vassalized the neighbouring Karachays and Balkars and the Ossetians.[17] The term Circassia is also used as the collective name of various Circassian states that were established within historical Circassian territory, such as Zichia.[8][9][18]

Legally and internationally, the Treaty of Belgrade, which was signed between Austria and the Ottoman Empire in 1739, provided for the recognition of the independence of Eastern Circassia. Both the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire recognized it under witness from the other great powers of the time. The Congress of Vienna also stipulated the recognition of the independence of Circassia. In 1837, Circassian leaders sent letters to a number of European states requesting diplomatic recognition. Following this, the United Kingdom recognized Circassia.[19][20] However, following the outbreak of the Russo-Circassian War, the Russian Empire did not recognize Circassia as an independent nation and instead treated it as Russian land under rebel occupation, despite having no control or ownership over the region.[21] Russian generals often referred to the Circassians as "mountaineers", "bandits", and "mountain scum" rather than by their ethnonym.[21][22]

The Russian conquest of Circassia created the Circassian diaspora; the overwhelming majority of Circassians today live outside of their ancestral homeland, mostly in Turkey and other parts of the Middle East.[23][24][25][26] Only about 14% of the global Circassian population lives in the modern-day Russian Federation.

Etymology

The words Circassia and Circassian (/sərˈkæsiənz/ sər-KASS-ee-ənz) are exonyms, Latinized from the word Cherkess, which is of debated origin.[27][28] One view is that its root stems from Turkic languages, and that the term means "head choppers" or "warrior killers" accounting for the successful battle practices of the Circassians.[29] There are those who argue that the term comes from Mongolian Jerkes, meaning "one who blocks a path".[19][30] Some believe it comes from the ancient Greek name of the region, Siraces. According to another view, its origin is Persian.

In languages spoken geographically close to the Caucasus, the native people originally had other names for the Circassia, but with Russian influence, the name has been settled as Cherkessia/Circassia. It is the same or similar in many world languages that cite these languages.

Circassians themselves don't use the term "Circassia", and refer to their country as Адыгэ Хэку (Adıgə Xəku) or Адыгей (Adıgey).

Another historical name for the country was Zichia (Zyx or the Zygii), who were described by the ancient Greek intellectual Strabo as a nation to the north of Colchis.[31]

Geography

Circassia was located north of Western Asia, near the northeastern Black Sea coast. Before the Russian conquest of the Caucasus (1763–1864), it covered the entire fertile plateau and the steppe of the northwestern region of the Caucasus, with an estimated population of 1 million.[citation needed]

Circassia's historical great range extended from the Taman Peninsula in the west, to the town of Mozdok in today's North Ossetia–Alania in the east. Historically, Circassia covered the southern half of today's Krasnodar Krai, the Republic of Adygea, Karachay-Cherkessia, Kabardino-Balkaria, and parts of North Ossetia–Alania and Stavropol Krai, bounded by the Kuban River on the north which separated it from the Russian Empire.

On the Black Sea coast, the climate is warm and humid, while being moderate in the lowlands and cooler in the highlands. Most of Circassia is frost free for more than half the year. There are steppe meadows in the plains, beech and oak forests in the foothills, and pine forests and alpine meadows in the mountains.[32]

Sochi is considered by many Circassians as their traditional capital city.[33] According to Circassians, the 2014 Winter Olympic village is built in an area of mass graves of Circassians after their defeat by the Russians Empire in 1864.[34]

Statehood and politics

Institute of the Grand Prince of Circassia

Between 1427 and 1453, Inal the Great conquered all Circassian principalities and declared himself the Grand Prince of Circassia. Following his death, Circassia was divided again.[35]

The influential principalities of Circassia regularly met to elect a Grand Prince (Пщышхо) among them, with the only condition being that the prince can trace descent from Inal the Great. The existence of such an institute is confirmed by foreign sources. In the eyes of foreign observers, the Grand Prince was considered the king of the Circassians.[36] However, the individual tribes were greatly autonomous and the title was mostly symbolic. In 1237, the Dominican monks Richard and Julian, as part of the Hungarian embassy, visited Circassia and the main city of this country Matrega, located on the Taman Peninsula. In Matrega, the embassy received a good reception from the Grand Prince.[37]

In the 14th and 15th centuries Italian documents concerning the relationship between the consul of Kafa and Circassia clearly indicate the absolutely special status of the ruler of Circassia. This status allowed the senior prince of Circassia to correspond with the Pope. The letter of Pope John XXII , addressed to the Grand Prince of Zichia (Circassia) Verzacht, dates back to 1333, in which the Roman pontiff thanked the ruler for his diligence in introducing the Catholic faith among his subjects. Verzacht's power status was so high that following his example some other Circassian princes adopted Catholicism.[38]

Confederation

Circassia traditionally consisted of more than a dozen principalities. Some of these principalities were divided into large feudal estates, characterized by the stability of political status. Within these territories there were numerous feudal possessions of princes (pshi). The Circassian state was a federal state consisting of four levels of government: Village council (чылэ хасэ, made up of village elders and nobles), district council (made up of representatives from 7 neighboring village councils), regional council (шъолъыр хасэ, made up from neighboring district councils), people's council (лъэпкъ зэфэс, where every council had a representative). A central government emerged during the mid to late 1800s. Prior to that, the institute of grand prince was mostly symbolic.

In 1807, Shuwpagwe Qalawebateqo self-proclaimed himself as the leader of the Circassian confederation, and divided Circassia into 12 major regions.[39][40][41][42] In 1827, Ismail Berzeg officially declared the military confederation of the Circassian tribes and by 1839 united a significant part of Circassia under his control.[43][44] In 1839, the Circassians declared Bighuqal (Anapa) as their new capital and Hawduqo Mansur was declared the new leader of the Circassian Confederation. He kept this title until his death.[45][46][44] In 1848, Muhammad Amin was the leader of Circassia.[47][48][49] After learning that a warriorly scholar has arrived, thousands of families moved to the Abdzakh region to accept his rule.[50] Seferbiy Zaneqo assumed power after Amin's departure, but died the next year.

In June 1860, at a congress of representatives of Circassians, a parliament was formed as the highest legislative body of Circassia. Being a political resistance council and the legislature of Circassia,[51][52][53] the parliament was established in the capital of Sochi (Adyghe: Шъачэ, romanized: Ş̂açə) on June 13, 1860 and Qerandiqo Berzeg was elected as the head of the parliament and the nation.[54][55]

External relations

Legally and internationally, the Treaty of Belgrade 1739 provided for the recognition of the independence of Eastern Circassia (Kabarda), where both the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire recognized it, and the great powers at the time witnessed the treaty. The Congress of Vienna held in the period between 1814 and 1815 also stipulated the recognition of the independence of Circassia. In 1837, Circassian leaders sent letters to European countries requesting legal recognition. Following this, the United Kingdom recognized Circassia.[19][20] However, during the Russian-Circassian War, the Russian Empire did not recognize Circassia as an independent region, and treated it as Russian land under rebel occupation, despite having no control or ownership over the region.[21] Russian generals referred to the Circassians not by their ethnic name, but as "mountaineers", "bandits", and "mountain scum".[21][22]

The Circassian Parliament launched large-scale foreign policy activities. First of all, an official memorandum was drafted addressed to Tsar Alexander II. The text of the memorandum was presented to the tsar by the leaders of the Parliament during the latter's visit to Circassia in September 1861. The Parliament also accepted an appeal to the Ottoman and European governments. Special envoys were sent to Istanbul and London to seek diplomatic and military support. The activities of the Circassian government received the full support of public organizations, so the Circassian Committee of Istanbul and London supported Circassia. Thus, if not de jure, then de facto Circassia acquired the features of a subject of international law.[54]

Relations with the Ottoman Empire

In the 16th century, the English traveler Edmund Spencer, who traveled to the shores of the Caucasus, quotes a Circassian saying about the Ottoman sultan:

Circassian blood flows in the veins of the Sultan. His mother, his harem are Circassian; his slaves are Circassians, his ministers and generals are Circassians. He is the head of our faith and also of our race.

Army

Circassia for centuries lived under the threat of external invasions, so the whole way of life of the Circassians was militarized. The governor of Astrakhan wrote to Peter I:[56]

One thing I can praise about the Circassians is that they are all warriors.

Circassia developed the so-called "Culture of War". Honorable combat was a big part of this culture, during hostilities, it was considered strictly unacceptable to set fire to homes or crops, especially bread, even from enemies. It was considered inadmissible to leave the bodies of dead comrades on the battlefield. It was considered a great disgrace in Circassia to fall alive into the hands of the enemy, so Russian officers who later fought in Circassia noted that it was very rare to succeed in capturing Circassians, as they would go as far as suicide. Johann von Blaramberg noted:

When they see that they are surrounded, they give their lives dearly, never surrendering.

The Russian army, after invading Circassia and ethnically cleansing the Circassians in the Circassian genocide, adopted some parts of Circassian military uniforms - from weapons (Shashka and Circassian sabers, daggers, Circassian saddles, Circassian horses) to uniforms (Cherkeska, burqa, papaha).[56]

Known ancient and medieval rulers

Known rulers of the region include:

- 400–383 BC: Hekataios[57]

- 383–355 BC: Oktamasades

- 100s: Stachemfak[58]

- 400s: Dawiy[59]

- 500s: Bakhsan Dawiqo[59]

- 700s–800s: Lawristan[60][61]

- 800s–900s: Weche[62]

- 900s: Hapach[63][64]

- 900s–1022: Rededya[65][66][67]

- 1200s: Abdunkhan

- 1200s–1237: Tuqar[68][69][70]

- 1237–1239: Tuqbash[71]

- 1300s: Verzacht[72]

- 1427–1453: Inal the Great

- 1470s: Petrezok[73][74]

- 1530s–1542: Kansavuk[75]

History

Pseudoscientific origin

Turkish nationalist groups and proponents of modern day Pan-Turkism have claimed that the Circassians are of Turkic origin, but no scientific evidence has been published to support this claim and it has been strongly denied by ethnic Circassians,[76] impartial research,[77][78][79][80][81][82] linguists[83] and historians[84] around the world. The Circassian language does not share notable similarities to the Turkish language except for borrowed words. According to various historians, the Circassian origin of the Sindo-Meot tribes refutes the claim that the Circassians are of Turkic ethnic origin.[77]

Ancient Era

Maikop Civilization

Miyequap (Maikop) civilization was established in 3000 BC. Circassians were known by many different names in ancient times. "Kerket" and "Sucha" are examples.[85] In 1200 BC, Circassians fought alongside the Hittites against the Egyptians.[85]

Sindica

The Sindica Kingdom was founded in 800 BC. During this period, Greeks (Greeks) and Sindi-Meotay tribes lived in Circassia. Under the roof of this state, Sindi-Meotians in the region became the ancestors of the Circassian people.[91] The Greek poet Hipponax, who lived in the 5th century BC, and Herodotus later mentioned the Sindis. Strabo also mentions the Capitol of Sindia, located near the Black Sea coast. Information on Sindica has been learned from Greek documents and archaeological finds,[87] and there is not much detail. It is not known exactly when the Sindica Kingdom was established, but it is known that the Sindis had a state and trade relations with the Greeks before the establishment of the Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast. It is also known that the kingdom of Sindica was a busy trading state where artists and merchants were accommodated.[87][92][93][94][95][96] Circassians could not establish a union for a long time after this state.

Medieval Era

The most detailed description of medieval Circassia was made by Johannes de Galonifontibus in 1404.[97] From his writing it follows that at the turn of the XIV and XV centuries, Circassia expanded its borders to the north to the mouth of the Don, and he notes that “the city and port of Tana is located in the same country in Upper Circassia, on the Don River, which separates Europe from Asia".[98]

Feudalism began to emerge in Circassians by the 4th century. As a result of Armenian, Greek and Byzantine influence, Christianity spread throughout the Caucasus between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD.[99][100] During that period the Circassians (referred to at the time as Kassogs)[101] began to accept Christianity as a national religion, but did not abandon all elements of their indigenous religious beliefs. Circassians established many states, but could not achieve political unity. From around 400 AD wave after wave of invaders began to invade the lands of the Adyghe people, who were also known as the Kasogi (or Kassogs) at the time. They were conquered first by the Bulgars (who originated on the Central Asian steppes). Outsiders sometimes confused the Adyghe people with the similarly named Utigurs (a branch of the Bulgars), and both peoples were sometimes conflated under misnomers such as "Utige". Following the dissolution of the Khazar state, the Adyghe people were integrated around the end of the 1st millennium AD into the Kingdom of Alania. Between the 10th and 13th centuries Georgia had influence on the Adyghe Circassian peoples.

In 1382, Circassian mamluks took the Mamluk throne, the Burji dynasty took over and the Mamluks became a Circassian state. The Mongols, who started invading the Caucasus in 1223, destroyed some of the Circassians and most of the Alans. The Circassians, who lost most of their lands during the ensuing Golden Horde attacks, had to retreat to the back of the Kuban River. In 1395 Circassians fought violent wars against Tamerlane, Tamerlane plundered Circassia.[102]

King Inal the Great

Inal is called the "Prince of Princes" by Circassians and Abkhazians, because he united all Circassian tribes and established the Circassian state. According to popular belief, Inal is the ancestor of Kabardian, Besleney, Chemguy and Hatuqwai princes.

Inal, who during the 1400s[103] owned land in the Taman peninsula, established an army consisting mostly of the Khegayk tribe and declared that his goal was to unite the Circassians,[104] which were divided into many states at that time, under a single state, and after declaring his own princedom, conquered all of Circassia one by one.[105]

Circassian nobles and princes tried to prevent Inal's rise, but in a battle near the Msimta River, 30 Circassian lords were defeated by Inal and his supporters. Ten of them were executed, while the remaining twenty lords took an oath of allegiance and joined the forces of Inal's new state.[106] Inal, who ruled Western Circassia, established the Kabarda region in Eastern Circassia in 1434 and drove the Crimean Tatar tribes in the Circassian lands to the north of the Kuban River in 1438,[107] and as a result of his effective expansions, he was ruling all[106][107] of the Circassian land.

The capital of this new Circassian state founded by Inal became the city of Shanjir, built in the Taman region where he was born and raised.[108][109][110][111] Although the exact location of the city of Shanjir is unknown, the most supported theory is that it is the Krasnaya Batareya district, which fits the descriptions of the city made by Klarapoth and Pallas.[108][112][113]

Although he united the Circassians, Inal still wanted to include the cousin people, the Abkhaz, in his state. Abkhaz dynasties Chachba and Achba announced that they would side with Inal in a possible war. Inal, who won the war in Abkhazia, officially conquered Northern Abkhazia and the Abkhaz people recognized the rule of Inal, and Inal finalized his rule in Abkhazia.[107][114][106][115][116] One of the stars on the flag of Abkhazia represents Inal.

Inal divided his lands between his sons and grandchildren in 1453 and died in 1458. Following this, Circassian tribal principalities were established. Some of these are Chemguy founded by Temruk, Besleney founded by Beslan, Kabardia founded by Qabard, and Shapsug founded by Zanoko.

According to the Abkhaz claim, Inal died in North Abkhazia.[117] Although most sources cite this theory, researches and searches in the region have shown that Inal's tomb is not here.[118] According to Russian explorer and archaeologist Evgeniy Dimitrievich Felitsin, Inal's tomb is not in Abkhazia. In a map published in 1882, Felitsin has shown great importance to Inal, and placed his grave in the Ispravnaya region in Karachay-Cherkessia, not in Abkhazia. He added that there are ancient sculptures, mounds, tombs, churches, castles and ramparts in this area, which would be an ideal tomb for someone like Inal.[118][119]

At the end of the 15th century, a detailed description of Circassia and of its inhabitants was made by Genovese traveller and ethnographer Giorgio Interiano.[120]

Modern Era

Kanzhal

In 1708, Circassians paid a great tribute to the Ottoman sultan in order to prevent Tatar raids, but the sultan did not fulfill the obligation and the Tatars raided all the way to the center of Circassia, robbing everything they could.[121] For this reason, Kabardian Circassians announced that they would never pay tribute to the Crimean Khan and the Ottoman Sultan again[122] to Kabardia under the leadership of the Crimean khan Kaplan-Girey to conquer the Circassians and ordered him collect the tribute.[123][124] The Ottomans expected an easy victory against the Kabardinians, but the Circassians won because of the strategy set up by the Kazaniko Jabagh.[121][125][126][127][128][129]

The Crimean army was completely destroyed overnight. The Crimean Khan Kaplan-Giray barely managed to save his life, and was humiliated, all the way to his shoes taken, leaving his brother, son, field tools, tents and personal belongings.[121]

Russo-Circassian War

In 1714, Peter I established a plan to occupy the Caucasus. Although he was unable to implement this plan, he laid the political and ideological foundation for the occupation to take place. Catherine II started putting this plan into action. The Russian army was deployed on the banks of the Terek River.[130]

The Russian military tried to impose authority by building a series of forts, but these forts in turn became the new targets of raids and indeed sometimes the highlanders actually captured and held the forts.[131] Under Yermolov, the Russian military began using a strategy of disproportionate retribution for raids. Russian troops retaliated by destroying villages where resistance fighters were thought to hide, as well as employing assassinations, kidnappings and the execution of whole families.[7] Because the resistance was relying on sympathetic villages for food, the Russian military also systematically destroyed crops and livestock and killed Circassian civilians.[132][133] Circassians responded by creating a tribal federation encompassing all tribes of the area.[133] In 1840 Karl Friedrich Neumann estimated the Circassian casualties at around one and a half million.[134] Some sources state that hundreds of thousands of others died during the exodus.[135] Several historians use the phrase "Circassian massacres"[136] for the consequences of Russian actions in the region.[137]

In a series of sweeping military campaigns lasting from 1860 to 1864... the northwest Caucasus and the Black Sea coast were virtually emptied of Muslim villagers. Columns of the displaced were marched either to the Kuban [River] plains or toward the coast for transport to the Ottoman Empire... One after another, entire Circassian tribal groups were dispersed, resettled, or killed en masse.[138]

Circassians established an assembly called "Great Freedom Assembly" in the capital city of Shashe (Sochi) on June 25, 1861. Haji Qerandiqo Berzedj was appointed as the head of the assembly. This assembly asked for help from Europe,[139] arguing that they would be forced into exile soon. However, before the result was achieved, Russian General Kolyobakin invaded Sochi and destroyed the parliament[140] and no country opposed this.[139]

In May 1864, a final battle took place between the Circassian army of 20,000 Circassian horsemen and a fully equipped Russian army of 100,000 men.[citation needed] Circassian warriors attacked the Russian army and tried to break through the line, but most were shot down by Russian artillery and infantry.[82] The remaining fighters continued to fight as militants and were soon defeated. All 20,000 Circassian horsemen died in the war. The Russian army began celebrating victory on the corpses of Circassian soldiers, and so May 21, 1864, was officially the end of the war.[141]

Circassian Genocide

The proposal to deport the Circassians was ratified by the Russian government, and a flood of refugee movements began as Russian troops advanced in their final campaign.[78] Circassians prepared to resist and hold their last stand against Russian military advances and troops.[142] With the refusal to surrender, Circassian civilians were targeted one by one by the Russian military with thousands massacred and the Russians started to raid and burn Circassian villages,[133] destroy the fields to make it impossible to return, cut trees down and drive the people towards the Black Sea coast.[79]

Although the main target of the genocide was the Circassians, some Abkhaz, Abazin, Chechen, Ossetian and other Muslim Caucasian[143] communities were also affected. Although it is not known exactly how many people are affected, researchers have suggested that at least 75%, 90%,[144][145] 94%,[146] or 95–97%[147] (not including the other ethniticies such as Abkhaz) of the ethnic Circassian population are affected. Considering these rates, calculations including those taking into account the Russian government's own archival figures, have estimated a loss 600,000–1,500,000. It is estimated that the population of Kabardins in Circassia was reduced from 500,000 to 35,000; the Abzakhs from 260,000 to 14,600; and the Natukhajs from 240,000 to merely 175 persons.[148] The Shapsugh tribe which numbered some 300,000 were reduced to 3,000 people. Ivan Drozdov, a Russian officer who witnessed the scene at Qbaada in May 1864 as the other Russians were celebrating their victory remarked:

On the road, our eyes were met with a staggering image: corpses of women, children, elderly persons, torn to pieces and half-eaten by dogs; deportees emaciated by hunger and disease, almost too weak to move their legs, collapsing from exhaustion and becoming prey to dogs while still alive.

— Drozdov, Ivan. "Posledniaia Bor’ba s Gortsami na Zapadnom Kavkaze". pp. 456–457.

The Ottoman Empire regarded the Adyghe warriors as courageous and experienced. It encouraged them to settle in various near-border settlements of the Ottoman Empire in order to strengthen the empire's borders.

According to Walter Richmond

Circassia was a small independent nation on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. For no reason other than ethnic hatred, over the course of hundreds of raids the Russians drove the Circassians from their homeland and deported them to the Ottoman Empire. At least 600,000 people lost their lives to massacre, starvation, and the elements while hundreds of thousands more were forced to leave their homeland. By 1864, three-fourths of the population was annihilated, and the Circassians had become one of the first stateless peoples in modern history.[80]

As of 2020, Georgia was the only country to classify the events as genocide, while Russia actively denies the Circassian genocide, and classifies the events as a simple migration of "undeveloped barbaric peoples".[attribution needed] Russian nationalists continue to celebrate the day on May 21 each year as a "holy conquest day", when the Russian Empire's occupation of the Caucasus ended. Circassians commemorate May 21 every year as the Circassian Day of Mourning.

Population

There are twelve historic Adyghe (Circassian: Адыгэ, Adyge) princedoms or tribes of Circassia (three democratic and nine aristocratic); Abdzakh, Besleney, Bzhedug, Hatuqwai, Kabardian, Mamkhegh, Natukhai, Shapsug, Temirgoy, Ubykh, Yegeruqwai and Zhaney.[149]

Today, about 700,000 Circassians remain in historical Circassia in today's Russia. The 2010 Russian Census recorded 718,727 Circassians, of which 516,826 are Kabardians, 124,835 are Adyghe proper, 73,184 are Cherkess and 3,882 Shapsugs.[150] The largest Circassian population resides in Turkey (pop. 1,400,000–6,000,000).[151] Circassian populations also exist in other countries, such as Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Serbia, Egypt and Israel, but are considerably smaller.[152][153][citation needed]

National religion

Circassia gradually went through the following various religions: Paganism, Christianity, and then Islam.[154]

Paganism

The ancient beliefs of the Circassians were based on animism and magic, within the framework of the customary rules of Xabze. Although the main belief was Monistic-Monotheistic, they prayed using water, fire, plants, forests, rocks, thunder, and lightning. They performed their acts of worship accompanied by dance and music in the sacred groves used as temples. An old priest led the ceremony, accompanied by songs of prayer, and supplications. It was aimed at protecting newborn babies from diseases and the evil eye.[155] Another important aspect was ancestors and honor. They believed that the goal of man's earthly existence is the perfection of the soul, which corresponds to the maintenance of honour, manifestation of compassion, gratuitous help, which, along with valour, and bravery of a warrior, enables the human soul to join the soul of the ancestors with a clear conscience.[156]

Judaism

Some Circassian tribes converted to Judaism in the past as a result of the settlement of approximately 20 thousand Jews in 8th-century Circassia, along with the relations established with the Turkic-Jewish Khazar Khaganate.[155] Judaism in Circassia eventually assimilated into Christianity and Islam.

Christianity

It is the tradition of the early church that Christianity made its first appearance in Circassia in the 1st century AD via the travels and preaching of the Apostle Andrew,[157] but recorded history suggests that, as a result of Greek and Byzantine influence, Christianity first spread throughout Circassia between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD.[99][100][158] The spread of the Catholic faith was only possible with the Latin Conquest of Constantinople by the crusaders and the establishment of the Latin state. The Catholic religion was adopted by the Circassians following Farzakht, a distinguished figure who greatly contributed to the spread of this religion in his country. The pope sent him a letter in 1333 thanking him for his effort, as an indication of his gratitude. For Circassians, the most important and attractive personality in all Christian teachings was the personality of Saint George. They saw in him the embodiment of all the virtues respected in the Caucasus. His name in Circassian is "Aushe-Gerge".

Christianity in Circassia experienced its final collapse in the 18th century when all Circassians accepted Islam. The ex-priests joined the Circassian nobility and were given the name "shogene" (teacher) and over time this name became a surname.

Today Christianity is still widespread among Mozdok Kabardians.[159]

Islam

In 815 AD, Islam arrived in Circassia with the efforts of two Arab preachers called Abu Ishaq and Muhammad Kindi, and the first Circassian Muslim community was established with a small amount of followers. A small Muslim community in Circassia has existed since the Middle Ages, but the widespread adoption of Islam occurred after 1717.[160] Travelling Sufi preachers and the increasing threat of an invasion from Russia helped expedite the spread of Islam in Circassia.[160][161][162] Circassian scholars educated in the Ottoman Empire boosted the spread of Islam.[163]

Circassian nationalism

Under Russian and Soviet rule, ethnic and tribal divisions between Circassians were promoted, resulting in several different statistical names being used for various parts of the Circassian people (Adyghes, Cherkess, Kabardins, Shapsugs). Consequently, Circassian nationalism has developed. Circassian nationalism is the desire among Circassians all over the world to preserve their culture and save their language from extinction,[164][165] achieve full international recognition of the Circassian genocide,[166][167][168] globally revive Adyghe Xabze among Circassians,[169][170][171] return to their homeland Circassia,[172][173][174][175] and ultimately reestablish an independent Circassian state.[174][175][176] There is also an effort among Circassians to unite under the name Circassian (Adyghe) in Russian Censuses to reflect and revive the concept of the Circassian nation. The overwhelming majority of the diaspora already tends to call itself "only Circassian".

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ The Circassian state was a federal state consisting of four levels of government: Village council (чылэ хасэ, made up of village elders), district council (made up of representatives from 7 neighboring village councils), regional council (шъолъыр хасэ, made up from neighboring district councils), people's council (лъэпкъ зэфэс, where every council had a representative). There wasn't a central ruler until the 1800s, and the leader was symbolic in nature. A central government existed during the mid to late 1800s.

- ^ "Dünyayı yıkımdan kurtaracak olan şey : Çerkes tipi hükümet sistemi". Ghuaze. 5 November 2022.

- ^ “Алфавитный список народов, обитающих в Российской Империи” Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Демоскоп Weekly, № 187 - 188, 24 января - 6 февраля 2005 ve buradan alınma olarak: Papşu, Murat. Rusya İmparatorluğu’nda Yaşayan Halkların Alfabetik Listesinde Kafkasyalılar Archived 18 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Genel Komite, HDP (2014). "The Circassian Genocide". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ a b "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok - Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ a b де Галонифонтибус И., 1404, II. Черкесия (Гл. 9).

- ^ a b Хотко С. К. Садзы-джигеты.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–381.

- ^ Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatnâme, II, 61-70; VII, 265-295

- ^ Genel Komite, HDP (2014). "The Circassian Genocide". www.hdp.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013-04-09). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Geçmişten günümüze Kafkasların trajedisi: uluslararası konferans, 21 Mayıs 2005 (in Turkish). Kafkas Vakfı Yayınları. 2006. ISBN 978-975-00909-0-5.

- ^ "UNPO: The Circassian Genocide". unpo.org. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Tarihte Kafkasya - ismail berkok | Nadir Kitap". NadirKitap (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Bilge, Sadık Müfit. "Çerkezler: Kafkaslar'da yaşayan halklardan biri". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ де Галонифонтибус И., 1404, I. Таты и готы. Великая Татария: Кумания, Хазария и другие. Народы Кавказа (Гл. 8), Прим. 56..

- ^ a b c Bashqawi, Adel (15 September 2017). Circassia: Born to Be Free. Xlibris. ISBN 978-1543447644.

- ^ a b Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Circassians: A Handbook.

- ^ a b c d Richmond, Walter (9 April 2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ a b Capobianco, Michael (13 October 2012). "Blood on the Shore: The Circassian Genocide". Caucasus Forum.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0813560694.

- ^ Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 528. ISBN 978-1317464006.

- ^ "single | The Jamestown Foundation". Jamestown. Jamestown.org. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ Douglas Harper, Etymonline states: "1550s, in reference to a people people of the northern Caucasus along the Black Sea, from Circassia, Latinized from Russian Cherkesŭ, which is of unknown origin. Their name for themselves is Adighe. Their language is non-Indo-European. The race was noted for the "fine physical formation of its members, especially its women" [Century Dictionary], who were much sought by neighboring nations as concubines, etc."

- ^ James Stuart Olson, et al., eds. "Cherkess".An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing, 1994. p. 150. ISBN 9780313274978 "The Beslenei (Beslenej) are located between the upper Urup and Khozdya rivers, and along the Middle Laba River, in the western reaches of the North Caucasus."

- ^ Yamisha, Jonty. The Circassians: An Introduction

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. back cover. ISBN 978-0-8135-6069-4.

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 11.2

- ^ "Circassians". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Home thoughts from abroad: Circassians mourn the past—and organise for the future. The Economist. 2012-05-26.

- ^ Spelen zijn op massagraven. Archived 2014-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Nederlandse Omroep Stichting 2014-02-03

- ^ "Prince Inal the Great (I): The Tomb of the Mighty Potentate Is Located in Circassia, Not Abkhazia". Amjad Jaimoukha. Circassian Voices. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020.

- ^ "Черкесия: черты социо-культурной идентичности". Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ De facto Ungariae Magnae a fretre Riccardo invento tempori domini Gregorii Noni. // Исторический архив. 1940. Т. 3. С. 96.)

- ^ Atti della Societa Ligure di storia patria. T. VII, f. 2. 737; Колли Л. Кафа в период владения ею банком св. Георгия (1454-1475) // Известия Таврической Ученой Архивной комиссии. No. 47. Симферополь, 1912. С. 86.)

- ^ Berkok, İsmail. Tarihte Kafkasya. İstanbul Matbaası.

- ^ Berkok, İsmail. Tarihte Kafkasya

- ^ KAFFED, Çerkes Özgürlük Meclisi

- ^ These regions were Shapsugo-Natukhaj, Abdzakh, Chemguy, Barakay, Bzhedug, Kabardo-Besleney, Hatuqway, Makhosh, Bashilbey, Taberda, Abkhazia and Ubykh.

- ^ Hatajuqua, Ali. "Hadji-Ismail Dagomuqua Berzeg, Circassian Warrior and Diplomat". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 7 (38).

- ^ a b D, S. Kronolojik Savaş Tarihi

- ^ Хункаров, Д. Урыс-Адыгэ зауэ

- ^ A.Ü. Arşivi, XII.V, Çerkez tarihi liderleri

- ^ Казиев Ш.М. Имам Шамиль / Изд. 2-е испр. — М.: Молодая гвардия, 2003. — 378 с.

- ^ AKAK, Vol. X, p.590, document No. 544, Vorontsov to Chernyshev (secret), 8 [20] November 1847, No. 117

- ^ Карлгоф Н. Магомет-Амин II // Кавказский календарь на 1861 год. — Тф.: Тип. Гл. управ. намес. кавказского, 1860. — С. 77—102 (отд. 4).

- ^ NA, F.O. 195/443, “Report of Mehmed Emin…”, 15 August 1854

- ^ Фадеев А.В. Указ. соч.

- ^ Фадеев А.В. Убыхи в освободительном движении на Западном Кавказе //Исторический сборник. – М.; Л., 1935. – No. 4.

- ^ Блиев М.М., Дегоев В.В. Кавказская война. – М., 1994.

- ^ a b "Черкесия: черты социо-культурной идентичности". Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ Ruslan, Yemij (August 2011). Soçi Meclisi ve Çar II. Aleksandr ile Buluşma. Archived 2020-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Русско-Черкесская война 1763—1864 гг. и ее последствия

- ^ Polyaenus names Hekataios, the king of the Sindi kingdom of Circassians, who ruled between 400-383 BC.

- ^ Arrian (89–146) mentions a king of Zichia (West Circassia) named Stachemfak (Adyghe: Стахэмфакъу)

- ^ a b D, S. Çerkes Krallar, Hükümdarlar "In the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, the Goths settled in the north of the Black Sea. There were constant wars with the Circassian kingdoms. Prince Baksan, one of the 8 sons and eldest of King Daw, was one of the rare leaders who made his mark in the wars against the Goths, was one of the rare leaders to whom a statue was erected, and died with his eighty warriors in a war against the Goths, in which his 7 brothers joined him."

- ^ Natho, Kadir. Ancient Circassian History

- ^ D, S. Çerkes Krallar, Hükümdarlar "Lawristan is the 6th century King of the Circassians and is known for his war with the Avars. Upon his refusal to come under Avar rule, Avar Khan with an army of 60 thousand destroyed the Black Sea coast."

- ^ D, S. Çerkes Krallar, Hükümdarlar

- ^ Zenkovsky, Sergei A. Medieval Russia’s Cronicles, 58-59

- ^ D, S. Çerkes Krallar, Hükümdarlar "The leader of the Circassian tribes, Hapach, with his army of horsemen and allied principalities, attacked Sarkel, a city of the Khazars. The Khazar army was defeated and the Sarkel prince and his surviving army were shackled by their feet and imprisoned."

- ^ The Laurentian Codex provides the following information: "In 1022, Prince Mstislav the Brave, who at the time was the prince of Tmutarakan, started a military operation against the Alans. During the operation, he encountered the Kassogian army commanded by Rededya. To avoid unnecessary bloodshed, Mstislav and Rededya, who possessed an extraordinary physical force, decided to have a personal fight, with the condition that the winner would be considered the winner of the battle. The fight lasted some hours and, eventually, Rededya was knocked to the ground and stabbed with a knife."

- ^ Pdf scans of the original text

- ^ from The Complete Collection of Russian Manuscripts (in Russian)

- ^ Historian Rashid-ad-Din in the Persian Chronicles, wrote that the Circassian king Tuqar was killed in battle against the Mongols

- ^ Рашид ад-Дин. Сборник летописей. М.-Л., 1952. Т. 2. С. 39

- ^ L.I. Lavrov. “Kuzey Kafkasya’da Moğol İstilası”

- ^ ФАЗЛАЛЛАХ РАШИД-АД-ДИН->СБОРНИК ЛЕТОПИСЕЙ->ПУБЛИКАЦИЯ 1941 Г.->ТЕКСТ

- ^ In his letter to the king of Zichia, Verzacht/Ferzakht, Pope John XXII thanks the Governor of Circassians for his assistance in implementing the Christian faith among the Circassians. Verzacht's power and status was so high that his example was followed by the rest of the Circassian princes, who took the Roman Catholic faith.

- ^ A contract was signed between the ruler of Circassia and the ruler of Caffa, naming another ruler of Zichia: "Petrezok , the paramount lord of Zichia". Under the contract, Zichia would supply large quantities of grain to Caffa.

- ^ Kressel R. Ph. The Administration of Caffa under the Uffizio di San Giorgio. University of Wisconsin, 1966. P. 396

- ^ Malʹbakhov, Boris (2002). Kabarda na ėtapakh politicheskoĭ istorii : (seredina XVI-pervai︠a︡ chetvertʹ XIX) veka. Moskva: Pomatur. ISBN 5-86208-106-2.

- ^ "Ulusal Toplu Katalog - Tarama". www.toplukatalog.gov.tr. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ a b "Çerkesler Türk mü?". 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Russian Federation – Adygey". Minority Rights. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Russian Federation – Karachay and Cherkess". Minority Rights. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Russian Federation – Kabards and Balkars". Minority Rights. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Circassian. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Çerkesler Türk değildir". 2006. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Circassian: A Most Difficult Language". 29 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Circassian". Archived from the original on 30 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Çerkes tarihinin kronolojisi". Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Гос. Эрмитаж, инв. No. М. 59.1320. Монета разломана на две части, склеена.

- ^ a b c "К находке синдской монеты в Мирмекии" (in Russian). Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ Сопутствующий монете материал хранится в ЛОИА АН СССР. Керамический материал представлен обломками фасосских амфор и чернолаковой керамикой (инв. No.No. М. 59. 1308-1319)

- ^ М. И. Ростовцев, Эллинство и иранство на юге России, СПб., 1908, стр. 123; В. И. Мошинская, О государстве синдов, ВДИ. 1946, No. 3, стр. 203 сл.; Н. В. Анфимов, К вопросу о населении Прикубанья в скифскую эпоху, СА, XI, 1949, стр. 258; он же, Из прошлого Кубани, Краснодар. 1958, стр. 85; он же, Синдика в VI-IV вв. до н. э., "Труды Краснодарского гос. пед. ин-та", вып. XXXIII, Краснодар, 1963, стр. 195; В. Д. Блаватский, Античная культура в Северном Причерноморье, КСИИМК, XXXV, М.- Л., 1950; стр. 34; он же, Рабство и его источники в античных государствах Северного Причерноморья. СА, XX, 1954, стр. 32, 35; он же, Процесс исторического развития античных государств в Северном Причерноморье, сб. "Проблемы истории Северного Причерноморья в античную эпоху", М., 1959, стр. 11; В. П. Шилов, Население Прикубанья конца VII - середины IV в. до н. э. по материалам городищ и грунтовых могильников, Автореф. дисс, М.- Л., 1951, стр. 13; он же, Синдские монеты, стр. 214; Н. И. Сокольский и Д. Б. Шелов, Историческая роль античных государств Северного Причерноморья, сб. "Проблемы истории Северного Причерноморья", М., 1959, стр. 54; Д. Б. Шелов, Монетное дело Боспора, стр. 47; Т. В. Блаватская, Очерки политической истории Боспора в V-IV вв. до н. э., М-, 1959, стр. 94; Э. Берзин, Синдика, Боспор и Афины в последней четверти V в. до н. э., ВДИ, 1958, No. 1, стр. 124; F. И. Крупнов, Древняя история Северного Кавказа, М., 1960, стр. 373; "История Кабардино-Балкарской АССР", т. I, M., 1967, стр. 48; "Очерки истории Карачаево-Черкесии", т. I, Ставрополь, 1967, стр. 45-48: Т. X. Кумыков, К вопросу о возникновении и развитии феодализма у адыгских народов, сб. "Проблемы возникновения феодализма у народов СССР", М., 1969, стр. 191-194.

- ^ В боспорской нумизматике известны монеты, приписанные исследователями Аполлонии и Мирмекию и датированные первой половиной V в. до н. э. Однако первые вызывают большие споры и сомнения ввиду отсутствия города с таким названием в источниках; вторые - с эмблемой муравья - также не могут быть отнесены безоговорочно к Мирмекию. См. В. Ф. Гайдукевич, Мирмекий, Варшава, 1959, стр. 6.

- ^ Древнее царство Синдика, 2007

- ^ General İsmail Berkok, Tarihte Kafkasya,İstanbul,1958, s.135-136.

- ^ Turabi Saltık, Sindika Krallığı, Jineps, Ocak 2007, s.5.

- ^ Tamara V.Polovinkina,Çerkesya, Gönül Yaram, Ankara,2007, s.21-45.

- ^ Генрих Ананенко,Сыд фэдагъа Синдикэр?,Адыгэ макъ gazetesi,07.01.1992.

- ^ V.Diakov-S.Kovalev,İlkçağ Tarihi, Ankara,1987, s.345-355,506-514.

- ^ де Галонифонтибус И., 1404.

- ^ де Галонифонтибус И., 1404, I. Таты и готы. Великая Татария: Кумания, Хазария и другие. Народы Кавказа (Гл. 8).

- ^ a b The Penny Magazine. London, Charles Knight, 1838. p. 138.

- ^ a b Minahan, James. One Europe, Many Nations: a Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport, USA, Greenwood, 2000. p. 354.

- ^ Jaimoukha, Amjad M. (2005). The Chechens: A Handbook. Psychology Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Çerkes tarihinin kronolojisi". Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Shora Nogma has 1427 (per Richmond, Northwest Caucasus, kindle@610). In a later book (Circassian Genocide kindle @47) Richmond reports the legend that Inal reunited the princedoms after they were driven into the mountains by the Mongols. In a footnote (@2271) he says that Inal was a royal title among the Oguz Turks

- ^ Caucasian Review. Vol. 2. Munich (München), 1956. Pp.; 19; 35.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey E. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC. OCLC 939825134.

- ^ a b c "The Legendary Circassian Prince Inal, by Vitaliy Shtybin". Vitaliy Shtybin. Abkhaz World. 17 May 2020. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Prenslerın Prensı İnal Nekhu (Pşilerın Pşisi İnal İnekhu)". Kağazej Jıraslen. 2013. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Prince Inal the Great of Circassia, II: Shanjir, the Fabled Capital of Inal's Empire". 2013. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020.

- ^ Броневский, Семён, Новейшие географические и исторические известия о Кавказе, Москва, 1823.

- ^ Захаров, Н. (Краснодар), “Пограничное укрепление Боспорского государства на Северном Кавказе и Краснобатарейное городище”, Советская археология II, Москва, 1937.

- ^ Шевченко, Н. Ф., “Краснобатарейное городище. Старые проблемы, новые исследования”, Пятая Кубанская археологическая конференция. Материалы конференции, Краснодар, 2009, 434-439.

- ^ Pallas, Peter Simon, Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire, in the Years 1793 and 1794, London: John Stockdale, Piccadilly, 1812 (2 vols). [Peter-Simon Pallas’ (1741-1811) second and most picturesque travel]

- ^ Абрамзон, М. Г., Фролова, Н. А., “Горлов Ю. В. Клад золотых боспорских статеров II в. н. э. с Краснобатарейного городища: [Краснодар. край]”, ВДИ, № 4, 2000, С. 60-68.

- ^ Papaskʻiri, Zurab, 1950- (2010). Абхазия : история без фальсификации. Izd-vo Sukhumskogo Gos. Universiteta. ISBN 9941016526. OCLC 726221839.

- ^ Klaproth, Julius Von, 1783—1835. (2005). Travels in the Caucasus and Georgia performed in the years 1807 and 1808 by command of the Russian government. Elibron Classics

- ^ The 200-year Mingrelia-Abkhazian war and the defeat of the Principality of Mingrelia by the Abkhazians of XVII-XVIII cc.

- ^ Asie occidentale aux XIVe-XVIe siècles, 2014.

- ^ a b "Prince Inal the Great (I): The Tomb of the Mighty Potentate Is Located in Circassia, Not Abkhazia". Amjad Jaimoukha. Circassian Voices. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020.

- ^ Археологическая карта Кубанской области, Фелицын, Евгений Дмитриевич, 1882.

- ^ Biblioteca Italiana. Vita de' Zichi chiamati Ciarcassi di G. Interiano (in Latin)

- ^ a b c "Путешествие господина А. де ла Мотрэ в Европу, Азию и Африку". www.vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Василий Каширин. "Ещё одна "Мать Полтавской баталии"? К юбилею Канжальской битвы 1708 года". www.diary.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Подборка статей к 300-летию Канжальской битвы". kabardhorse.ru. Archived from the original on 17 April 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Рыжов К. В. (2004). Все монархи мира. Мусульманский Восток. XV-XX вв. М.: «Вече». p. 544. ISBN 5-9533-0384-X. Archived from the original on 2012-12-22.

- ^ "Описание Черкесии". www.vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2019.. 1724 год.

- ^ ""Записки" Гербера Иоганна Густава". www.vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "Энгельберт Кемпфер". www.vostlit.info. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Василий Каширин. "Ещё одна "Мать Полтавской баталии"? К юбилею Канжальской битвы 1708 года". www.diary.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Cw (2009-10-15). "Circassian World News Blog: Documentary: Kanzhal Battle". Circassian World News Blog. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ Weismann, Ein Blick auf die Circassianer

- ^ Serbes, Nahit (2012). Yaşayan Efsane Xabze. Phoenix Yayınları. ISBN 9786055738884.

- ^ Çurey, Ali (2011). Hatti-Hititler ve Çerkesler. Chiviyazıları Yayınevi. ISBN 9786055708399.

- ^ a b c Ahmed 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Neumann 1840

- ^ Shenfield 1999

- ^ Levene 2005:299

- ^ Levene 2005: 302

- ^ King 2008: 94–6.

- ^ a b Richmond, Walter. Circassian Genocide. p. 72.

- ^ Prof.Dr. ĞIŞ Nuh (yazan), HAPİ Cevdet Yıldız (çeviren). Adigece'nin temel sorunları-1. Адыгэ макъ,12/13 Şubat 2009

- ^ "Arşivlenmiş kopya". Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Shenfield 1999, p. 151.

- ^ "Caucasus Survey". Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "145th Anniversary of the Circassian Genocide and the Sochi Olympics Issue". Reuters. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (20 May 2011). "Georgia Says Russia Committed Genocide in 19th Century". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Sarah A.S. Isla Rosser-Owen, MA Near and Middle Eastern Studies (thesis). The First 'Circassian Exodus' to the Ottoman Empire (1858–1867), and the Ottoman Response, Based on the Accounts of Contemporary British Observers. Page 16: "... with one estimate showing that the indigenous population of the entire north-western Caucasus was reduced by a massive 94 per cent". Text of citation: "The estimates of Russian historian Narochnitskii, in Richmond, ch. 4, p. 5. Stephen Shenfield notes a similar rate of reduction with less than 10 per cent of the Circassians (including the Abkhazians) remaining. (Stephen Shenfield, "The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide?", in The Massacre in History, p. 154.)"

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. Page 132: ". If we assume that Berzhe's middle figure of 50,000 was close to the number who survived to settle in the lowlands, then between 95 percent and 97 percent of all Circassians were killed outright, died during Evdokimov's campaign, or were deported."

- ^ А.Суриков. Неизвестная грань Кавказской войны Archived 2013-08-19 at the Wayback Machine(in Russian)

- ^ Gammer, Mos%u030Ce (2004). The Caspian Region: a Re-emerging Region. London: Routledge. p. 67.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Population by ethnicity". Russian Census. GKU. 2010. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ "People groups: Kabardian + Adyge". Country: Turkey. Joshua project. 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ "World: Europe Circassians flee Kosovo conflict". BBC News. 1998-08-02. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ "NJ Circassians join international group to protest Winter Olympics in Russia". NJ. 9 February 2010.

- ^ Чамокова, Сусанна Туркубиевна (2015). "Трансформация Религиозных Взглядов Адыгов На Примере Основных Адыгских Космогонических Божеств". Вестник Майкопского государственного технологического университета.

- ^ a b Övür, Ayşe (2006). "Çerkes mitolojisinin temel unsurları: Tanrılar ve Çerkesler" (PDF). Toplumsal Tarih. 155. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ Khabze.info. Khabze: the religious system of Circassians.

- ^ Antiquitates christianæ, or, The history of the life and death of the holy Jesus as also the lives acts and martyrdoms of his Apostles: in two parts, by Taylor, Jeremy, 1613–1667. p. 101.

- ^ Jaimoukha, Amjad M. (2005). The Chechens: A Handbook. Psychology Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Мэздогу адыгэ: кто такие моздокские кабардинцы". kavtoday.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ a b Natho, Kadir I. Circassian History, pp. 123–24.

- ^ Shenfield, Stephen D. "The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide". In Levene and Roberts, The Massacre in History, p. 150.

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide, p. 59.

- ^ Serbes, Nahit. "Çerkeslerde inanç ve hoşgörü" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-12.

- ^ "Çerkes milliyetçiliği nedir?". Ajans Kafkas (in Turkish). 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "'Çerkes Milliyetçiliği' Entegre (Kapsayıcı) Bir İdeolojidir". www.ozgurcerkes.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "152 yıldır dinmeyen acı". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Kayseri Haberi: Çerkeslerden anma yürüyüşü". Sözcü. 21 May 2017. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Çerkes Forumu, Çerkes Soykırımını yıl dönümünde kınadı". Milli Gazete (in Turkish). 14 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Paul Golbe. Window on Eurasia: Circassians Caught Between Two Globalizing "Mill Stones", Russian Commentator Says. On Windows on Eurasia, January 2013.

- ^ Авраам Шмулевич. Хабзэ против Ислама. Промежуточный манифест.

- ^ North Caucasus Insurgency Admits Killing Circassian Ethnographer. Caucasus Report, 2010. Retrieved 24-09-2012.

- ^ "Suriyeli Çerkesler, Anavatanları Çerkesya'ya Dönmek İstiyor". Haberler.com (in Turkish). 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ "Kaffed - Dönüş". www.kaffed.org (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ a b "Kaffed - Evimi Çok Özledim". www.kaffed.org (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2021-02-17.

- ^ a b Besleney, Zeynel. "A COUNTRY STUDY: THE REPUBLIC OF ADYGEYA". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Özalp, Ayşegül Parlayan (23 September 2013). "Savbaş Ve Sürgün, Kafdağı'nın Direnişi | Atlas" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2021-02-17.

Cited works

- Ahmed, Akbar (2013). The Thistle and the Drone: How America's War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-2379-0.

- Shenfield, Stephen D. (1999). "The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide?". In Levene, Mark; Roberts, Penny (eds.). The Massacre in History. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 149–162. ISBN 978-1-57181-935-2.

- "Иоанн де Галонифонтибус". Сведения о народах Кавказа (1404 г.). Baku: Элм. 1979.

- * "Хотко С. К. Садзы-джигеты. Происхождение и историко-культурный портрет абазинского субэтноса // Сайт «АПСУАРА» История и культура Абхазии (www.apsuara.ru) 25 April 2014 ; а также, первоначально — на Сайте «Авдыгэ макъ» (www.adygvoice.ru)". 12 апреля 2011. — Часть 1. Archived 2013-08-15 at the Wayback Machine; 29 апреля 2011. — Часть 2. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine; 29 апреля 2011. — Часть 3. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine; 29 апреля 2011. — Часть 4. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

General references

- Bell, James Stanislaus. Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 (in English).

- Bullough, Oliver. Let Our Fame Be Great: Journeys Among the Defiant People of the Caucasus. Allen Lane, 2010. ISBN 978-1846141416.

- Jaimoukha, Amjad. The Circassians: A Handbook, London: Routledge, New York: Routledge & Palgrave, 2001. ISBN 978-0700706440.

- Jaimoukha, Amjad. Circassian Culture and Folklore: Hospitality, Traditions, Cuisine, Festivals and Music. Bennett & Bloom, 2010. ISBN 978-1898948407.

- Kaziev, Shapi, and Igor Karpeev (Повседневная жизнь горцев Северного Кавказа в XIX в.). Everyday Life of the Caucasian Highlanders: The 19th Century. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiy, 2003. ISBN 5-235-02585-7

- King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0195392395.

- Levene, Mark. Genocide in the Age of the Nation-State. Volume II: The Rise of the West and the Coming of Genocide. London: I. B. Tauris, 2005. ISBN 978-1845110574.

- Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide, Rutgers University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780813560694.

External links

Media related to Circassia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Circassia at Wikimedia Commons