Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

William Z. Ripley | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 16, 1867 Medford, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 16, 1941 (aged 74) Edgecomb, Maine, U.S. |

| Academic career | |

| Institution | Columbia University (1893–1901) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1895–1901) Harvard University (1901) |

| Alma mater | Columbia University Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

William Zebina Ripley (October 13, 1867 – August 16, 1941) was an American economist, lecturer at Columbia University, professor of economics at MIT, professor of political economy at Harvard University, and anthropologist of race. Ripley was famous for his criticisms of American railroad economics and American business practices in the 1920s and 1930s, and later for his tripartite racial theory of Europe. His contribution to the anthropology of race was later taken up by racial physical anthropologists, eugenicists, white supremacists, Nordicists, and racists in general, and it was considered a valid academic work at the time, although today it is considered to be a prime example of scientific racism and pseudoscience.[1][2]

He was born in Medford, Massachusetts, in 1867 to Nathaniel L. Ripley and Estimate R. E. Ripley (née Baldwin). He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for his undergraduate education in engineering, graduating in 1890, and he received a master's and doctorate degree from Columbia University in 1892 and 1893 respectively. In 1893, he was married to Ida S. Davis.

From 1893 to 1901, Ripley lectured on sociology at Columbia University and from 1895 to 1901, he was a professor of economics at MIT. From 1901 onwards, he was a professor of political economics at Harvard University.[3]

He was a corresponding member of the Anthropological Society of Paris, the Roman Anthropological Society, the Cherbourg Society of Natural Sciences, and in 1898 and 1900 to 1901, he was the vice president of the American Economic Association.[4]

In 1899, he authored a book entitled The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study, which had grown out of a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Like many Americans of his time, at every level of education, Ripley believed that the concept of race was explanatory of human difference. Even further, he believed it to be the central engine to understanding human history, although his work also afforded strong weight to environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to Races of Europe, that:

Ripley's book, written to help finance his children's education, became a widely accepted work of anthropology, due to its careful writing, compilation of seemingly valid data, and close criticism of the data of many other anthropologists in Europe and the United States.

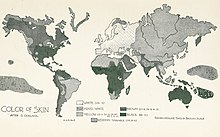

Ripley based his conclusions about race on his attempts to correlate anthropometric data with geographical data, especially using the cephalic index, which at the time was considered a reliable anthropometric measure. Based on these measurements and other socio-geographical data, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races:

In his book, Ripley also proposed the idea that "Africa begins beyond the Pyrenees", as he wrote in page 272:

Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with others on the topic of human difference, including those who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were at least ten European races (such as Joseph Deniker, who Ripley saw as his chief rival). The conflict between Ripley and Deniker was criticized by Jan Czekanowski, who states, that "the great discrepancies between their claims decrease the authority of anthropology", and what is more, he points out, that both Deniker and Ripley had one common feature, as they both omitted the existence of an Armenoid race, which Czekanowski claimed to be one of the four main races of Europe, met especially among the Eastern Europeans and Southern Europeans.[7] Writing at a time when such racialist theories were widely accepted among academics, Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1908 for his contributions to anthropology.

The Races of Europe, overall, became an influential book of the era in the then-accepted field of racial taxonomy.[8] Ripley's tripartite system of racial classification was especially championed by the racist propagandist Madison Grant, who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own Nordic type (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a master race.[9] It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's racist ideology is present in Ripley's original work.[citation needed]

Ripley worked under Theodore Roosevelt on the United States Industrial Commission in 1900, helping negotiate relations between railway companies and anthracite coal companies. He served on the Eight Hour Commission in 1916, adjusting railway wages to the new eight-hour workday. From 1917 to 1918, he served as Administrator of Labor Standards for the United States Department of War, and helped to settle railway strikes.

Ripley was the Vice President of the American Economics Association 1898, 1900, and 1901, and was elected president of it in 1933. From 1919 to 1920, he served as the chairman of the National Adjustment Commission of the United States Shipping Board, and from 1920 to 1923, he served with the Interstate Commerce Commission. In 1921, he was ICC special examiner on the construction of railroads. There, he wrote the ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of U.S. railways, which became known as the Ripley Plan.[10] In 1929, the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title Complete Plan of Consolidation. Numerous hearings were held by the ICC regarding the plan under the topic of "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems".[11][12][13] (In 1940, however, Congress declined to adopt the consolidation plan.[14])

Starting with a series of articles in the Atlantic Monthly in 1925 under the headlines of "Stop, Look, Listen!", Ripley became a major critic of American corporate practices. In 1926, he issued a well-circulated critique of Wall Street's practices of speculation and secrecy. He received a full-page profile in The New York Times with the headline, "When Ripley Speaks, Wall Street Heeds".[15] According to Time magazine, Ripley became widely known as "The Professor Who Jarred Wall Street".[16]

However, after an automobile accident in January 1927, Ripley suffered a nervous breakdown and was forced to recuperate at a sanitarium in Connecticut. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, he was occasionally credited with having predicted the financial disaster. In December 1929, The New York Times said:

He was unable to return to teaching until at least 1929. However, in the early 1930s, he continued to issue criticisms of the railroad industry labor practices. In 1931, he had also testified at a Senate banking inquiry, urging the curbing of investment trusts. In 1932, he appeared at the Senate Banking and Currency Committee, and demanded public inquiry into the financial affairs of corporations and authored a series of articles in The New York Times stressing the importance of railroad economics to the country's economy. Yet, by the end of the year he had suffered another nervous breakdown, and retired in early 1933.

Ripley died in 1941 at his summer home in East Edgecomb, Maine. An obituary in The New York Times implied that Ripley had predicted the 1929 crash with his "fearless exposés" of Wall Street practices, in particular his pronouncement that:

His book, Railway Problems: An Early History of Competition, Rates and Regulations, was republished in 2000 as part of a "Business Classic" series.[18]