Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| |

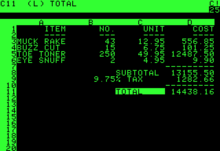

VisiCalc spreadsheet on an Apple II | |

| Developer(s) | Software Arts, published by VisiCorp |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 1979 |

| Stable release | VisiCalc Advanced Version

/ 1983 |

| Operating system | Apple II, Apple SOS, Atari 8-bit, CP/M, PET, HP Series 80, MS-DOS, Sony SMC-70, TRSDOS |

| Type | Spreadsheet |

| License | Commercial proprietary software |

| Website | danbricklin |

VisiCalc ("visible calculator")[1] is the first spreadsheet computer program for personal computers,[2] originally released for the Apple II by VisiCorp on October 17, 1979.[1][3] It is considered the killer application for the Apple II,[4] turning the microcomputer from a hobby for computer enthusiasts into a serious business tool, and then prompting IBM to introduce the IBM PC two years later.[5] More than 700,000 copies were sold in six years, and up to 1 million copies over its history.[citation needed] [6]

Initially developed for the Apple II computer using a 6502 assembler running on the Multics time-sharing system,[7][8][9] VisiCalc was ported to numerous platforms, both 8-bit and some of the early 16-bit systems. To do this, the company developed porting platforms that produced bug compatible versions. The company took the same approach when the IBM PC was launched, producing a product that was essentially identical to the original 8-bit Apple II version. Sales were initially brisk, with about 300,000 copies sold.[citation needed]

VisiCalc uses the A1 notation in formulas.[10][11]

When Lotus 1-2-3 was launched in 1983, taking full advantage of the expanded memory and screen of the IBM PC, VisiCalc sales declined so rapidly that the company was soon insolvent. In 1985, Lotus Development purchased the company[12] and ended sales of VisiCalc.[13][14]

VISICALC represented a new idea of a way to use a computer and a new way of thinking about the world. Where conventional programming was thought of as a sequence of steps, this new thing was no longer sequential in effect: When you made a change in one place, all other things changed instantly and automatically.

Dan Bricklin conceived of VisiCalc while watching a presentation at Harvard Business School. The professor was creating a financial model on a blackboard that was ruled with vertical and horizontal lines (resembling accounting paper) to create a table, and he wrote formulas and data into the cells. When the professor found an error or wanted to change a parameter, he had to erase and rewrite several sequential entries in the table. Bricklin realized that he could replicate the process on a computer using an "electronic spreadsheet" to view results of underlying formulae.[16]

Bob Frankston joined Bricklin at 231 Broadway, Arlington, Massachusetts, and the pair formed the Software Arts company, and developed the VisiCalc program in two months during the winter of 1978–79. Bricklin wrote:

with the years of experience we had at the time we created VisiCalc, we were familiar with many row/column financial programs. In fact, Bob had worked since the 1960s at Interactive Data Corporation, a major timesharing utility that was used for some of them and I was exposed to some at Harvard Business School in one of the classes.

Bricklin was referring to the variety of report generators that were in use at that time, including Business Planning Language (BPL) from International Timesharing Corporation (ITS) and Foresight from Foresight Systems. However, these earlier timesharing programs were not completely interactive, and they pre-dated personal computers.

Frankston described VisiCalc as a "magic sheet of paper that can perform calculations and recalculations [which] allows the user to just solve the problem using familiar tools and concepts". The Personal Software company began selling VisiCalc in mid-1979 for under US$100 (equivalent to $420 in 2023), after a demonstration at the fourth West Coast Computer Faire and an official launch on June 4 at the National Computer Conference. It requires an Apple II with 32K of random-access memory (RAM), and supports saving files to magnetic tape cassette or to the Apple Disk II floppy disk system.[17]

VisiCalc was unusually easy to use and came with excellent documentation. Apple's developer documentation cited the software as an example of one with a simple user interface.[18][19] Observers immediately noticed its power. Ben Rosen speculated in July 1979, that "VisiCalc could someday become the software tail that wags (and sells) the personal computer dog".[20][21] For the first 12 months, it was only available for Apple II, and became its killer app.[22][4][23] John Markoff wrote that the computer was sold as a "VisiCalc accessory",[24] and many bought $2,000 (equivalent to $8,400 in 2023) Apple computers to run the $100 software[21] — more than 25% of those sold in 1979 were reportedly for VisiCalc[20] — even if they already owned other computers.[25] Steve Wozniak said that small businesses, not the hobbyists he and Steve Jobs had expected, purchased 90% of Apple IIs.[26] Apple's rival Tandy Corporation used VisiCalc on Apple IIs at their headquarters.[27] Other software supports its Data Interchange Format (DIF) to share data.[19] One example is the Microsoft BASIC interpreter supplied with most microcomputers that ran VisiCalc. This allowed skilled BASIC programmers to write features, such as trigonometric functions, that VisiCalc lacked.[citation needed]

Bricklin and Frankston originally intended to fit the program into 16k memory, but they later realized that the program needed at least 32k. Even 32k is too small to support some features that the creators wanted to include, such as a split screen for text and graphics. However, Apple eventually began shipping all Apple IIs with 48k memory following a drop in RAM prices, enabling the developers to include more features. The initial release supported tape cassette storage, but that was quickly dropped.[citation needed]

At VisiCalc's release, Personal Software promised to port the program to other computers, starting with those with the MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor,[17] and versions appeared for Atari 8-bit computers and Commodore PET. Both of those were easy, because those computers have the same CPU as Apple II, and large portions of code were reused. The PET version, which contains two separate executables for 40 and 80-column models, was widely criticized for having a very small amount of worksheet space due to the developers' inclusion of their own custom DOS, which uses a large amount of memory. The PET only has 32k versus Apple II's available 48k.[citation needed]

Other ports followed for Apple III, the Zilog Z80-based Tandy TRS-80 Model I, Model II, Model III, Model 4, and Sony SMC-70. The TRS-80 Model I and Sony SMC-70 ports are the only versions of VisiCalc without copy protection. The HP 125 and Sony SMC-70 ports are the only CP/M version. Most versions are disk-based, but the PET VisiCalc came with a ROM chip that the user must install in one of the motherboard's expansion ROM sockets. The most important port is for the IBM PC, and VisiCalc became one of the first commercial packages available when the IBM PC shipped in 1981.[27] It quickly became a best-seller on this platform, though severely limited to be compatible with the versions for the 8-bit platforms. It is estimated that 300,000 copies were sold on the PC, bringing total sales to about 1 million copies.[28]

By 1982, VisiCalc's price had risen from $100 to $250 (equivalent to $790 in 2023).[29] Several competitors appeared in the market, such as SuperCalc[25] and Multiplan,[30] each of which have more features and corrected deficiencies in VisiCalc, but could not overcome its market dominance. A more dramatic change occurred with the 1983 launch of Lotus Development Corporation's Lotus 1-2-3, created by former Personal Software/VisiCorp employee Mitch Kapor, who had written VisiTrend and VisiPlot. Unlike the IBM PC version of VisiCalc, 1-2-3 was written to take full advantage of the PC's increased memory, screen, and performance. Yet it was designed to be as compatible as possible with VisiCalc, including the menu structure, to allow VisiCalc users to easily migrate to 1-2-3.[citation needed]

1-2-3 was almost immediately successful, and in 1984, InfoWorld wrote that sales of VisiCalc were "rapidly declining", stating, that it was "the first successful software product to have gone through a complete life cycle, from conception in 1978 to introduction in 1979 to peak success in 1982 to decline in 1983 to a probable death according to industry insiders in 1984". The magazine added that the company was slow to upgrade the software, only releasing an Advanced Version of VisiCalc for Apple II in 1983, and announcing one for the IBM PC in 1984.[30] By 1985, VisiCorp was insolvent. Lotus Development acquired Software Arts, and ended sales of the application.[28]

In 1983, Softline readers named VisiCalc tenth overall and the highest non-game on the magazine's Top Thirty list of Atari 8-bit programs by popularity.[33] II Computing listed it second on the magazine's list of top Apple II software as of late 1985, based on sales and market-share data.[34]

In its 1980 review, BYTE wrote "The most exciting and influential piece of software that has been written for any microcomputer application is VisiCalc [...] VisiCalc is the first program available on a microcomputer that has been responsible for sales of entire systems".[35] Creative Computing's review that year similarly concluded, "for almost anyone in business, education, or any science-related field it is [...] reason enough to purchase a small computer system in the first place".[36] Compute! reported, "Every Visicalc user knows of someone who purchased an Apple just to be able to use Visicalc".[22] Antic wrote in 1984, "VisiCalc isn't as easy to use as prepackaged home accounting programs, because you're required to design both the layout and the formulas used by the program. Because it is not pre-packaged, however, it's infinitely more powerful and flexible than such programs. You can use VisiCalc to balance your checkbook, keep track of credit card purchases, calculate your net worth, do your taxes—the possibilities are practically limitless."[37] The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software 1984 gave the application an overall A+ rating, praising its documentation and calling it "indispensable ... a straight 'A' classic".[19]

In 1999, Harvard Business School put up a plaque commemorating Dan Bricklin in the room where he had studied, saying, "Forever changed how people use computers in business."[38]

In 2006, Charles Babcock of InformationWeek wrote that, in retrospect, "VisiCalc was flawed and clunky, and couldn't do many things users wanted it to do", but also, "It's great because it demonstrated the power of personal computing."[39]

Since 2010, the anniversary of the October 17, 1979, launch of VisiCalc has been celebrated as Spreadsheet Day.[40][41]

VisiCalc is one of the earliest examples of metaphor-driven user interface design, due to its resemblance with paper spreadsheets. This metaphor made the program comprehensible and familiar to accountants, economists, and bookkeepers who were not used to using computers, and VisiCalc's release marked the point where "personal computers crossed the line from a hobbyist obsession to a compelling tool". Compared to paper spreadsheets, VisiCalc freed users to change numbers without having to recalculate the whole spreadsheet by hand, which, according to Steven Levy, "changed the perception of a spreadsheet from a document of hard costs into a modeling tool by which one tested business scenarios".[42]

Yeah, we called it all sorts of things – electronic ledger, electronic blackboard, visible calculator – that's what we finally based the name, VisiCalc, on.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

The first copy of VisiCalc for the Apple ][ (Version 1.37) went out the door on October 17, 1979.

The formal introduction of VisiCalc is scheduled for the National Computer Conference, being held June 4–7, in New York City.