Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Unit 731 | |

|---|---|

The unit 731 complex | |

| Location | Pingfang, Harbin, Heilongjiang, Manchukuo (now China) |

| Coordinates | 45°36′31″N 126°37′55″E / 45.60861°N 126.63194°E |

| Date | 1936–1945 |

Attack type | |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | Estimated 23,000[1] to 300,000[2] |

| Perpetrators | |

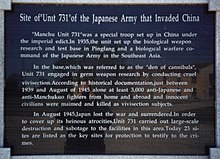

Unit 731 (Japanese: 731部隊, Hepburn: Nana-san-ichi Butai),[note 1] short for Manchu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment[3]: 198 and the Ishii Unit,[5] was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in lethal human experimentation and biological weapons manufacturing during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and World War II. Estimates vary as to how many were killed. Between 1936 and 1945, roughly 14,000 victims were murdered in Unit 731.[6] It is estimated that at least 300,000 individuals have died due to infectious illnesses caused by the activities of Unit 731 and its affiliated research facilities.[7] It was based in the Pingfang district of Harbin, the largest city in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (now Northeast China) and had active branch offices throughout China and Southeast Asia.

Established in 1936, Unit 731 was responsible for some of the most notorious war crimes committed by the Japanese armed forces. It routinely conducted tests on people who were dehumanized and internally referred to as "logs". Victims were further dehumanized by being confined in facilities referred to as "log cabins". Experiments included disease injections, controlled dehydration, biological weapons testing, hypobaric pressure chamber testing, vivisection, organ harvesting, amputation, and standard weapons testing. Victims included not only kidnapped men, women (including pregnant women) and children but also babies born from the systemic rape perpetrated by the staff inside the compound. The victims also came from different nationalities, with the majority being Chinese and a significant minority being Russian. Additionally, Unit 731 produced biological weapons that were used in areas of China not occupied by Japanese forces, which included Chinese cities and towns, water sources, and fields. All prisoners within the compound were killed to conceal evidence, and there were no documented survivors.

Originally set up by the military police of the Empire of Japan, Unit 731 was taken over and commanded until the end of the war by General Shirō Ishii, a combat medic officer. The facility itself was built in 1935 as a replacement for the Zhongma Fortress, a prison and experimentation camp. Ishii and his team used it to expand their capabilities. The program received generous support from the Japanese government until the end of the war in 1945. On 28 August 2002, Tokyo District Court ruled that Japan had committed biological warfare in China and consequently was responsible for the deaths of many residents.[8][9]

Both the Soviet Union and United States gathered data from the Unit after the fall of Japan. While twelve Unit 731 researchers arrested by Soviet forces were tried at the December 1949 Khabarovsk war crimes trials, they were sentenced lightly to the Siberian labor camp from two to 25 years, in exchange for the information they held.[10] Those captured by the US military were secretly given immunity.[11] The United States helped cover up the human experimentations and handed stipends to the perpetrators.[1] The US had co-opted the researchers' bioweapons information and experience for use in their own warfare program (resembling Operation Paperclip), as did the Soviet Union in building their bioweapons facility in Sverdlovsk using documentation captured from the Unit in Manchuria.[12][10][13]

Japan initiated its biological weapons program during the 1930s due to the prohibition of biological weapons in interstate conflicts by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. They reasoned that the ban verified its effectiveness as a weapon.[1] Japan's occupation of Manchuria began in 1931 after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.[14] Japan decided to build Unit 731 in Manchuria because the occupation not only gave the Japanese an advantage of separating the research station from their island, but also gave them access to as many Chinese individuals as they wanted for use as test subjects.[14] They viewed the Chinese as no-cost assets, and hoped this would give them a competitive advantage in biological warfare.[14] Most of the victims were Chinese, but many victims were also from different nationalities.[1] These facilities contained more than just medical research and experimentation areas; they also included spaces for detaining victims, essentially functioning as a prison.[15] The research and experimentation rooms were constructed around the detention area, allowing researchers to conduct their daily work while monitoring the prisoners.[15] Founded in 1936, Unit 731 expanded to include 3000 staff members, 150 structures, and the capacity to detain up to 600 prisoners concurrently for experimental purposes.[16]

Unit 731 was a clandestine division of Japan's Kwantung Army based in Manchuria during World War II. Led by Lieutenant General Shirō Ishii, the organization dedicated to the advancement of biological weaponry within the imperial army was commonly referred to as the Ishii Network.[17] The Ishii Network was headquartered at the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory, established in 1932 at the Japanese Army Military Medical School in Tokyo, Japan. Unit 731 was the first among several covert units established as offshoots of the research lab, serving as field stations and experimental sites for advancing biological warfare techniques. These efforts culminated in the experimental deployment of biological weapons on Chinese cities, a direct breach of the 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibiting the use of biological and chemical weapons in warfare. Participants in these activities were aware of the violations and recognized the inhumanity of using human subjects in laboratory experiments, prompting the establishment of Unit 731 and other secret units.[17]

Under the direction of Ishii Shiro, the Epidemic Prevention Research Laboratory was established following his return from a two-year exploration of American and European research institutions. With the endorsement of high-ranking military officials, it was established for the purpose of developing biological weapons. Ishii aimed to create biological weapons with humans as their intended victims, and Unit 731 was formed specifically to pursue this objective.[17] Ishii organized a secret research group, the "Tōgō Unit," for chemical and biological experimentation in Manchuria.

In 1936, Emperor Hirohito issued a decree authorizing the expansion of the unit and its integration into the Kwantung Army as the Epidemic Prevention Department.[18] It was divided at that time into the "Ishii Unit" and "Wakamatsu Unit", with a base in Xinjing. From August 1940 on, the units were known collectively as the "Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army" or "Unit 731" for short.[19]

One of Ishii's main supporters inside the army was Colonel Chikahiko Koizumi, who later served as Japan's Health Minister from 1941 to 1945. Koizumi had joined a secret poison gas research committee in 1915, during World War I, when he and other Imperial Japanese Army officers were impressed by the successful German use of chlorine gas at the Second Battle of Ypres, in which the Allies suffered 6,000 deaths and 15,000 wounded as a result of the chemical attack.[20][21]

Unit Tōgō was set into motion in the Zhongma Fortress, a prison and experimentation camp in Beiyinhe, a village 100 kilometers (62 mi) south of Harbin on the South Manchuria Railway. The prisoners brought to Zhongma included common criminals, captured bandits, anti-Japanese partisans, as well as political prisoners and people rounded up on trumped up charges by the Kempeitai. Prisoners were generally well fed on a diet of rice or wheat, meat, fish, and occasionally even alcohol in order to be in normal health at the beginning of experiments. Then, over several days, prisoners were eventually drained of blood and deprived of nutrients and water. Their deteriorating health was recorded. Some were also vivisected. Others were deliberately infected with plague bacteria and other microbes.[22] A prison break in the autumn of 1934, which jeopardized the facility's secrecy, and an explosion in 1935 (believed to be sabotage) led Ishii to shut down Zhongma Fortress. He then received authorization to move to Pingfang, approximately 24 kilometers (15 mi) south of Harbin, to set up a new, much larger facility.[23]

In addition to the establishment of Unit 731, the decree also called for the creation of an additional biological warfare development unit, called the Kwantung Army Military Horse Epidemic Prevention Workshop (later referred to as Manchuria Unit 100), and a chemical warfare development unit called the Kwantung Army Technical Testing Department (later referred to as Manchuria Unit 516). After the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, sister chemical and biological warfare units were founded in major Chinese cities and were referred to as Epidemic Prevention and Water Supply Units. Detachments included Unit 1855 in Beijing, Unit Ei 1644 in Nanjing, Unit 8604 in Guangzhou, and later Unit 9420 in Singapore. All of these units comprised Ishii's network, which, at its height in 1939, oversaw over 10,000 personnel.[24] Medical doctors and professors from Japan were attracted to join Unit 731 both by the rare opportunity to conduct human experimentation and the Army's strong financial backing.[25]

| Part of a series on |

| Statism in Shōwa Japan |

|---|

|

The military police and the Special Services Agency were responsible for finding victims to be test subjects for the unit, while a group of physicians was responsible for maintaining healthy victims and dispatching them for experimentations.[15] Not all individuals sent to Unit 731 underwent experiments; these experiments were reserved for healthy individuals, and once accepted into the program, the preservation of their health became a top priority.[15]

Human experiments involved intentionally infecting captives, especially Chinese prisoners of war and civilians, with disease-causing agents and exposing them to bombs designed to disperse infectious substances upon contact with the skin. There are no records indicating any survivors from these experiments; those who didn't die from infection were murdered for autopsy analysis.[16] After human experimentations, researchers commonly used either potassium cyanide or chloroform to kill survivors.[26]

According to American historian Sheldon H. Harris:

The Togo Unit employed gruesome tactics to secure specimens of select body organs. If Ishii or one of his co-workers wished to do research on the human brain, then they would order the guards to find them a useful sample. A prisoner would be taken from his cell. Guards would hold him while another guard would smash the victim's head open with an ax. His brain would be extracted off to the pathologist, and then to the crematorium for the usual disposal.[27]

Nakagawa Yonezo, professor emeritus at Osaka University, studied at Kyoto University during the war. While he was there, he watched footage of human experiments and executions from Unit 731. He later testified about the playfulness of the experimenters:[28]

Some of the experiments had nothing to do with advancing the capability of germ warfare, or of medicine. There is such a thing as professional curiosity: ‘What would happen if we did such and such?’ What medical purpose was served by performing and studying beheadings? None at all. That was just playing around. Professional people, too, like to play.

Prisoners were injected with diseases, disguised as vaccinations,[29] to study their effects. To study the effects of untreated venereal diseases, male and female prisoners were deliberately infected with syphilis and gonorrhea, then studied.[30] A special project, codenamed Maruta, used human beings for experiments. Test subjects were gathered from the surrounding population and sometimes euphemistically referred to as "logs" (丸太, maruta), used in such contexts as "How many logs fell?" This term originated as a joke on the part of the staff because the official cover story for the facility given to local authorities was that it was a lumber mill. According to a junior uniformed civilian employee of the Imperial Japanese Army working in Unit 731, the project was internally called "Holzklotz", from the German word for log.[31] In a further parallel, the corpses of "sacrificed" subjects were disposed of by incineration.[32] Researchers in Unit 731 also published some of their results in peer-reviewed journals, writing as though the research had been conducted on nonhuman primates called "Manchurian monkeys" or "long-tailed monkeys."[33]

At the age of 14, on the encouragement of a former school teacher, Hideo Shimizu joined the fourth group of minors assigned to Unit 731.[34] He recalled that he was brought to a specimen room where jars of various heights, with some reaching the height of an adult, were stored.[34] The jars held body parts from humans preserved in formalin, such as heads and hands.[34] There was also a pregnant woman's body with a large belly, where the lower part was exposed to reveal a fetus with hair. Shimizu discovered that the term "logs" was used dehumanizingly to refer to prisoners. He also learned that the prisoners were further dehumanized by being held in facilities referred to as "log cabins."[34]

Thousands of men, women, children, and infants interned at prisoner of war camps were subjected to vivisection, often performed without anesthesia and usually lethal.[35][36] In a video interview, former Unit 731 member Okawa Fukumatsu admitted to having vivisected a pregnant woman.[37] Vivisections were performed on prisoners after infecting them with various diseases. Researchers performed invasive surgery on prisoners, removing organs to study the effects of disease on the human body.[38]

Prisoners had limbs amputated in order to study blood loss. Limbs removed were sometimes reattached to the opposite side of victims' bodies. Some prisoners had their stomachs surgically removed and their esophagus reattached to the intestines. Parts of organs, such as the brain, lungs, and liver, were removed from others.[36] Imperial Japanese Army surgeon Ken Yuasa said that practising vivisection on human subjects was widespread even outside Unit 731,[39] estimating that at least 1,000 Japanese personnel were involved in the practice in mainland China.[40] Yuasa said that when he performed vivisections on captives, they were "all for practice rather than for research," and that such practises were "routine" among Japanese doctors stationed in China during the war.[32]

The New York Times interviewed a former member of Unit 731. Insisting on anonymity, the former Japanese medical assistant recounted his first experience in vivisecting a live human being, who had been deliberately infected with the plague, for the purpose of developing "plague bombs" for war.

"The fellow knew that it was over for him, and so he didn't struggle when they led him into the room and tied him down, but when I picked up the scalpel, that's when he began screaming. I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly, and his face was all twisted in agony. He made this unimaginable sound, he was screaming so horribly. But then finally he stopped. This was all in a day's work for the surgeons, but it really left an impression on me because it was my first time."[41]

Other sources provided information on usual practice in the Unit for surgeons to stuff a rag (or medical gauze) into the mouth of prisoners before commencing vivisection in order to stifle any screaming.[42]

Unit 731 and its affiliated units (Unit 1644 and Unit 100, among others) were involved in research, development and experimental deployment of epidemic-creating biological weapons in assaults against the Chinese populace (both military and civilian) throughout World War II.[6]

By 1939, Ishii had condensed his laboratory discoveries to six potent pathogens: anthrax, typhoid, paratyphoid, glanders, dysentery, and plague-infected human fleas. These agents were robust enough to ignite epidemics of considerable magnitude and resilient to aerial dispersal. This marked the initiation of the latter phase of Ishii's elaborate scheme: conducting field trials through military expeditions on unsuspecting civilians, aiming to devise a method of dissemination that would efficiently spread the pathogens in optimal concentrations for maximum devastation. His experiments involved the development of biodegradable bombs housing live rats and fleas infected with diseases, designed to explode mid-air, ensuring the safe descent of the infected creatures to the ground. Additionally, he deployed birds and bird feathers contaminated with anthrax from low-flying aircraft.[6]

Plague-infected fleas, bred in the laboratories of Unit 731 and Unit 1644, were spread by low-flying airplanes over Chinese cities, including coastal Ningbo and Changde, Hunan Province, in 1940 and 1941.[5] These operations killed tens of thousands with bubonic plague epidemics. An expedition to Nanjing involved spreading typhoid and paratyphoid germs into the wells, marshes, and houses of the city, as well as infusing them in snacks distributed to locals. Epidemics broke out shortly after, to the elation of many researchers, who concluded that paratyphoid fever was "the most effective" of the pathogens.[43][44]: xii, 173

The Library of Congress holds a set of three declassified documents from Unit 731, each more than 100 pages long, translated from Japanese to English. These documents provided comprehensive clinical records about the daily progression of various pathogens within the bodies of helpless prisoners who were experimented on by Japanese doctors.[45]

Japanese soldiers provided testimony indicating that the research program had the capability to manufacture substantial quantities of biological agents on a monthly basis: 300 kg of plague, 500–700 kg of anthrax, 800–900 kg of typhoid, and 1000 kg of cholera. Despite the significant production volumes, even small amounts of these bacteria possessed the potential to cause severe harm and fatalities.[46]

Ishii determined that fleas were an efficient carrier for transmitting plague, leading Unit 731 to focus on breeding significant numbers of fleas. To achieve this goal, Unit 731 had approximately 4500 flea incubators, each capable of producing at least 45 kg of fleas per cycle. The substantial quantities of plague bacteria and fleas generated, combined with the severe illness and death rates associated with plague infection, illustrate the formidable biological warfare production capabilities wielded by the Japanese. Japanese researchers had the required materials to apply the scientific method in conducting experiments involving inoculation and the creation of airborne bacterial bombs.[46]

Food items emerged as the preferred delivery mechanism for bacterial transmission. The unit maintained a stock of uncontaminated fruits. In a specific experiment conducted by Unit 731, typhoid was introduced into melons and cantaloupes. Following the contamination process, the bacterial density was measured. Once reaching a density level, the infected fruit was distributed to a small group of prisoners, with the objective of spreading typhoid throughout the entire group.[46]

Unit 731 conducted biological warfare field trials by attacking many Chinese civilian populations. During the period of 1940 to 1943, Japanese scientists found that using bacterial bombs for transmission wasn't effective, but they did find success in utilizing planes to spray microorganisms as a means of biological warfare delivery. Unit 100 also deployed aerial spraying methods akin to those examined by Unit 731.[46]

At least 12 large-scale bioweapon field trials were carried out, and at least 11 Chinese cities attacked with biological agents. An attack on Changde in 1941 reportedly led to approximately 10,000 biological casualties and 1,700 deaths among ill-prepared Japanese troops, in most cases due to cholera.[4] Japanese researchers performed tests on prisoners with bubonic plague, cholera, smallpox, botulism, and other diseases.[47] This research led to the development of the defoliation bacilli bomb and the flea bomb used to spread bubonic plague.[48] Some of these bombs were designed with porcelain shells, an idea proposed by Ishii in 1938.

These bombs enabled Japanese soldiers to launch biological attacks, infecting agriculture, reservoirs, wells, as well as other areas, with anthrax- and plague-carrier fleas, typhoid, cholera, or other deadly pathogens. During biological bomb experiments, researchers dressed in protective suits would examine the dying victims. Infected food supplies and clothing were dropped by airplane into areas of China not occupied by Japanese forces. In addition, poisoned food and candy were given to unsuspecting victims. Plague fleas, infected clothing, and infected supplies encased in bombs were dropped on various targets. The resulting cholera, anthrax, and plague were estimated to have killed at least 400,000 Chinese civilians.[49] Tularemia was also tested on Chinese civilians.[50]

Due to pressure from numerous accounts of the biowarfare attacks, Chiang Kai-shek sent a delegation of army and foreign medical personnel in November 1941 to document evidence and treat the afflicted. A report on the Japanese use of plague-infected fleas on Changde was made widely available the following year but was not addressed by the Allied Powers until Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a public warning in 1943 condemning the attacks.[51][52]

In December 1944, the Japanese Navy explored the possibility of attacking cities in California with biological weapons, known as Operation PX or Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. The plan for the attack involved Seiran aircraft launched by Sentoku submarine aircraft carriers upon the West Coast of the United States—specifically, the cities of San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The planes would spread weaponized bubonic plague, cholera, typhus, dengue fever, and other pathogens in a biological terror attack upon the population. The submarine crews would infect themselves and run ashore in a suicide mission.[53][54][55][56] Planning for Operation PX was finalized on March 26, 1945, but shelved shortly thereafter due to the strong opposition of Chief of General Staff Yoshijirō Umezu. Umezu later explained his decision as such: "If bacteriological warfare is conducted, it will grow from the dimension of war between Japan and America to an endless battle of humanity against bacteria. Japan will earn the derision of the world."[57]

Human targets were used to test grenades positioned at various distances and in various positions. Flamethrowers were tested on people.[58] Victims were also tied to stakes and used as targets to test pathogen-releasing bombs, chemical weapons, shrapnel bombs with varying amounts of fragments, and explosive bombs as well as bayonets and knives.

To determine the best course of treatment for varying degrees of shrapnel wounds sustained on the field by Japanese Soldiers, Chinese prisoners were exposed to direct bomb blasts. They were strapped, unprotected, to wooden planks that were staked into the ground at increasing distances around a bomb that was then detonated. It was surgery for most, autopsies for the rest.

Army Engineer Hisato Yoshimura conducted experiments by taking captives outside, dipping various appendages into water of varying temperatures, and allowing the limb to freeze.[61] Once frozen, Yoshimura would strike their affected limbs with a short stick, "emitting a sound resembling that which a board gives when it is struck."[62] Ice was then chipped away, with the affected area being subjected to various treatments. Military personnel of the Unit referred to Yoshimura as a "scientific devil" and a "cold-blooded animal" due to his strictness and involvement in mass killings and inhumane scientific test, which included soaking the fingers of a three-day-old child in water containing ice and salt.[63]

Naoji Uezono, a member of Unit 731, described in a 1980s interview a grisly scene where Yoshimura had "two naked men put in an area 40–50 degrees below zero and researchers filmed the whole process until [the subjects] died. [The subjects] suffered such agony they were digging their nails into each other's flesh."[64] Yoshimura's lack of remorse was evident in an article he wrote for the Japanese Journal of Physiology in 1950 in which he admitted to using 20 children and a three-day-old infant in experiments which exposed them to zero-degree-Celsius ice and salt water.[65] Although this article drew criticism, Yoshimura denied any guilt when contacted by a reporter from the Mainichi Shimbun.[66]

Yoshimura developed a "resistance index of frostbite" based on the mean temperature 5 to 30 minutes after immersion in freezing water, the temperature of the first rise after immersion, and the time until the temperature first rises after immersion. In a number of separate experiments it was then determined how these parameters depend on the time of day a victim's body part was immersed in freezing water, the surrounding temperature and humidity during immersion, how the victim had been treated before the immersion ("after keeping awake for a night", "after hunger for 24 hours", "after hunger for 48 hours", "immediately after heavy meal", "immediately after hot meal", "immediately after muscular exercise", "immediately after cold bath", "immediately after hot bath"), what type of food the victim had been fed over the five days preceding the immersions with regard to dietary nutrient intake ("high protein (of animal nature)", "high protein (of vegetable nature)", "low protein intake", and "standard diet"), and salt intake (45 g NaCl per day, 15 g NaCl per day, no salt).[67] This original data is seen in the attached figure.

Unit members orchestrated forced sex acts between infected and non-infected prisoners to transmit the disease, as the testimony of a prison guard on the subject of devising a method for transmission of syphilis between patients shows:

Infection of venereal disease by injection was abandoned, and the researchers started forcing the prisoners into sexual acts with each other. Four or five unit members, dressed in white laboratory clothing completely covering the body with only eyes and mouth visible, rest covered, handled the tests. A male and female, one infected with syphilis, would be brought together in a cell and forced into sex with each other. It was made clear that anyone resisting would be shot.[68]

After victims were infected, they were vivisected at different stages of infection, so that internal and external organs could be observed as the disease progressed. Testimony from multiple guards blames the female victims as being hosts of the diseases, even as they were forcibly infected. Genitals of female prisoners that were infected with syphilis were called "jam-filled buns" by guards.[68]

Some children grew up inside the walls of Unit 731, infected with syphilis. A Youth Corps member deployed to train at Unit 731 recalled viewing a batch of subjects that would undergo syphilis testing: "one was a Chinese woman holding an infant, one was a White Russian woman with a daughter of four or five years of age, and the last was a White Russian woman with a boy of about six or seven."[68] The children of these women were tested in ways similar to their parents, with specific emphasis on determining how longer infection periods affected the effectiveness of treatments.

Female prisoners were forced to become pregnant for use in experiments. The hypothetical possibility of vertical transmission (from mother to child) of diseases, particularly syphilis, was the stated reason for the torture. Fetal survival and damage to mother's reproductive organs were objects of interest. Though "a large number of babies were born in captivity," there have been no accounts of any survivors of Unit 731, children included. It is suspected that the children of female prisoners were killed after birth or aborted.[68]

While male prisoners were often used in single studies, so that the results of the experimentation on them would not be clouded by other variables, women were sometimes used in bacteriological or physiological experiments, sex experiments, and as the victims of sex crimes. The testimony of a unit member that served as a guard graphically demonstrated this reality:

One of the former researchers I located told me that one day he had a human experiment scheduled, but there was still time to kill. So he and another unit member took the keys to the cells and opened one that housed a Chinese woman. One of the unit members raped her; the other member took the keys and opened another cell. There was a Chinese woman in there who had been used in a frostbite experiment. She had several fingers missing and her bones were black, with gangrene set in. He was about to rape her anyway, then he saw that her sex organ was festering, with pus oozing to the surface. He gave up the idea, left and locked the door, then later went on to his experimental work.[68]

In other tests, subjects were deprived of food and water to determine the amount of time until death; placed into low-pressure chambers until their eyes popped from the sockets; experimented upon to determine the relationship between temperature, burns, and human survival; hung upside down until death; crushed with heavy objects; electrocuted; dehydrated with hot fans;[69] placed into centrifuges and spun until death; injected with animal blood, notably with horse blood; exposed to lethal doses of X-rays; subjected to various chemical weapons inside gas chambers; injected with seawater; and burned or buried alive.[70][71] In addition to chemical agents, the properties of many different toxins were also investigated by the Unit. To name a few, prisoners were exposed to tetrodotoxin (pufferfish or fugu poison), heroin, Korean bindweed, bactal, and castor-oil seeds (ricin).[72][73] Massive amounts of blood were drained from some prisoners in order to study the effects of blood loss according to former Unit 731 vivisectionist Okawa Fukumatsu. In one case, at least half a liter of blood was drawn at two-to-three-day intervals.[74]

As stated above, dehydration experiments were performed on the victims. The purpose of these tests was to determine the amount of water in an individual's body and to see how long one could survive with a very low to no water intake. It is known that victims were also starved before these tests began. The deteriorating physical states of these victims were documented by staff at a periodic interval.

"It was said that a small number of these poor men, women, and children who became marutas were also mummified alive in total dehydration experiments. They sweated themselves to death under the heat of several hot dry fans. At death, the corpses would only weigh ≈1/5 normal bodyweight."

— Hal Gold, Japan's Infamous Unit 731, (2019)

Unit 731 also performed transfusion experiments with different blood types. Unit member Naeo Ikeda wrote:

In my experience, when A type blood 100 cc was transfused to an O type subject, whose pulse was 87 per minute and temperature was 35.4 degrees C, 30 minutes later the temperature rose to 38.6 degrees with slight trepidation. Sixty minutes later the pulse was 106 per minute and the temperature was 39.4 degrees. Two hours later the temperature was 37.7 degrees, and three hours later the subject recovered. When AB type blood 120 cc was transfused to an O type subject, an hour later the subject described malaise and psychroesthesia in both legs. When AB type blood 100 cc was transfused to a B type subject, there seemed to be no side effect.

— Man, Medicine, and the State: The Human Body as an Object of Government Sponsored Medical Research in the 20th Century (2006) pp. 38–39

Unit 731 tested many different chemical agents on prisoners and had a building dedicated to gas experiments. Some of the agents tested were mustard gas, lewisite, cyanic acid gas, white phosphorus, adamsite, and phosgene gas.[75] A former army major and technician gave the following testimony anonymously (at the time of the interview, this man was a professor emeritus at a national university):

In 1943, I attended a poison gas test held at the Unit 731 test facilities. A glass-walled chamber about three meters square [97 sq ft] and two meters [6.6 ft] high was used. Inside of it, a Chinese man was blindfolded, with his hands tied around a post behind him. The gas was adamsite (sneezing gas), and as the gas filled the chamber the man went into violent coughing convulsions and began to suffer excruciating pain. More than ten doctors and technicians were present. After I had watched for about ten minutes, I could not stand it any more, and left the area. I understand that other types of gasses were also tested there.

— Hal Gold, Japan's Infamous Unit 731, p. 349 (2019)

Takeo Wano, a former medical worker in Unit 731, said that he saw a Western man, who was vertically cut into two pieces, pickled in a jar of formaldehyde.[62] Wano guessed that the man was Russian because there were many Russians living in the area at that time.[62] Unit 100 also experimented with toxic gas. Phone booth-like tanks were used as portable gas chambers for the prisoners. Some were forced to wear various types of gas masks; others wore military uniforms, and some wore no clothes at all. Some of the tests have been described as "psychopathically sadistic, with no conceivable military application". For example, one experiment documented the time it took for three-day-old babies to freeze to death.[76][77]

Unit 731 also tested chemical weapons on prisoners in field conditions. A report authored by unknown researcher in the Kamo Unit (Unit 731) describes a large human experiment of yperite gas (mustard gas) on 7–10 September 1940. Twenty subjects were divided into three groups and placed in combat emplacements, trenches, gazebos, and observatories. One group was clothed with Chinese underwear, no hat, and no mask and was subjected to as much as 1,800 field gun rounds of yperite gas over 25 minutes. Another group was clothed in summer military uniform and shoes; three had masks and another three had no mask. They also were exposed to as much as 1,800 rounds of yperite gas. A third group was clothed in summer military uniform, three with masks and two without masks, and were exposed to as much as 4,800 rounds. Then their general symptoms and damage to skin, eye, respiratory organs, and digestive organs were observed at 4 hours, 24 hours, and 2, 3, and 5 days after the shots. Injecting the blister fluid from one subject into another subject and analyses of blood and soil were also performed. Five subjects were forced to drink a solution of yperite and lewisite gas in water, with or without decontamination. The report describes conditions of every subject precisely without mentioning what happened to them in the long run.[78] The following is an excerpt of one of these reports:

Number 376, dugout of the first area:

September 7, 1940, 6 pm: Tired and exhausted. Looks with hollow eyes. Weeping redness of the skin of the upper part of the body. Eyelids edematous, swollen. Epiphora. Hyperemic conjunctivae.

September 8, 6 am: Neck, breast, upper abdomen and scrotum weeping, reddened, swollen. Covered with millet-seed-size to bean-size blisters. Eyelids and conjunctivae hyperemic and edematous. Had difficulties opening the eyes.

September 8, 6 pm: Tired and exhausted. Feels sick. Body temperature 37 degrees Celsius. Mucous and bloody erosions across the shoulder girdle. Abundant mucous nose secretions. Abdominal pain. Mucous and bloody diarrhea. Proteinuria.

September 9, 7 am: Tired and exhausted. Weakness of all four extremities.

Low morale. Body temperature 37 degrees Celsius. Skin of the face still weeping.

— Man, Medicine, and the State: The Human Body as an Object of Government Sponsored Medical Research in the 20th Century (2006) p. 187

After Japan's defeat in World War II, the Japanese murdered every single prisoner in the unit. The remains were then buried in the Unit 731 grounds after being cremated.[79] The following testimony explains how the captives were murdered:

On August 11 and 12, after the end of the war, approximately 300 prisoners were disposed of. The prisoners were coerced into suicide by being given a piece of rope. One quarter of them hung themselves, and the remaining three quarters who would not consent to suicide were made to drink potassium cyanide and killed by injection. In the end all were taken care of. The prisoners were made to drink potassium cyanide by mixing it with water and putting it into bowls. The injections were most likely chloroform.[79]

In 2002, Changde, China, site of the plague flea bombing, held an "International Symposium on the Crimes of Bacteriological Warfare," which estimated that the number of people slaughtered by the Imperial Japanese Army germ warfare and other human experiments was around 580,000.[44]: xii, 173 The American historian Sheldon H. Harris states that over 200,000 died.[80][81] In addition to Chinese casualties, 1,700 Japanese troops in Zhejiang during Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign were killed by their own biological weapons while attempting to unleash the biological agent, indicating serious issues with distribution.[82] Harris also said plague-infected animals were released near the end of the war, and caused plague outbreaks that killed at least 30,000 people in the Harbin area from 1946 to 1948.[1]

Some test subjects were selected to gather a wide cross-section of the population and included common criminals, captured bandits, anti-Japanese partisans, political prisoners, homeless and mentally disabled people, which included infants, men, the elderly and pregnant women, as well as those rounded up by the Kenpeitai military police for alleged "suspicious activities." Unit 731 staff included approximately 300 researchers, including doctors and bacteriologists.[83]

At least 3,000 men, women, and children[3]: 117 [82]—of which at least 600 every year were provided by the Kenpeitai[84]—were subjected to Unit 731 experimentation conducted at the Pingfang camp alone, not including victims from other medical experimentation sites such as Unit 100.[85] Although 3,000 internal victims is the widely accepted figure in the literature, former Unit member Okawa Fukumatsu claims that there were at least 10,000 victims of internal experiments at the Unit, he himself vivisecting thousands.[37]

According to A. S. Wells, the majority of victims were Chinese,[39] with a lesser percentage being Russian, Mongolian, and Korean. They may also have included a small number of European, American, Indian, Australian, and New Zealander prisoners of war.[86][87][88] A member of the Yokusan Sonendan paramilitary political youth branch, who worked for Unit 731, stated that not only were Chinese, Russians, and Koreans present, but also Americans, British, and French people.[89] Sheldon H. Harris documented that the victims were generally political dissidents, communist sympathizers, ordinary criminals, impoverished civilians, and the mentally disabled.[90] Author Seiichi Morimura estimates that almost 70 percent of the victims who died in the Pingfang camp were Chinese (both military and civilian),[91] while close to 30 percent of the victims were Russian.[92]

No one who entered Unit 731 came out alive. Prisoners were usually received into Unit 731 at night in motor vehicles painted black with a ventilation hole but no windows.[93] The vehicle would pull up at the main gates and one of the drivers would go to the guardroom and report to the guard. That guard would then telephone to the "Special Team" in the inner-prison (Shiro Ishii's brother was head of this Special Team).[94][95] Then, the prisoners would be transported through a secret tunnel dug under the facade of the central building to the inner-prisons.[96] One of the prisons housed women and children (Building 8), while the other prison housed men (Building 7). Once at the inner-prison, technicians would take samples of the prisoners' blood and stool, test their kidney function, and collect other physical data.[97] Once deemed healthy and fit for experimentation, prisoners lost their names and were given a three-digit number, which they retained until their death. Whenever prisoners died after the experiments they had been subjected to, a clerk of the 1st Division struck their numbers off an index card and took the deceased prisoner's manacles to be put on new arrivals to the prison.[98]

There is at least one recorded instance of "friendly" social interaction between prisoners and Unit 731 staff. Technician Naokata Ishibashi interacted with two female prisoners, a 21-year-old Chinese woman and a 19-year-old Ukrainian woman. The two prisoners told Ishibashi that they had not seen their faces in a mirror since being captured and begged him to get one. Ishibashi snuck a mirror to them through a hole in the cell door.[99]

The prison cells had wooden floors and a squat toilet in each. There was space between the outer walls of the cells and the outer walls of the prison, enabling the guards to walk behind the cells. Each cell door had a small window in it. Chief of the Personnel Division of the Kwantung Army Headquarters Tamura Tadashi testified that, when he was shown the inner-prison, he looked into the cells and saw living people in chains, some moved around, others were lying on the bare floor and were in a very sick and helpless condition.[100] Former Unit 731 Youth Corps member Yoshio Shinozuka testified that the windows in these prison doors were so small that it was difficult to see in.[101] The inner-prison was a highly secured building complete with cast iron doors.[94] No one could enter without special permits and an ID pass with a photograph, and the entry/exit times were recorded.[101] The "special team" worked in these two inner-prison buildings. This team wore white overall suits, army hats, rubber boots, and pistols strapped to their sides.[94]

Despite the prison's status as a highly secure building, at least one unsuccessful escape attempt did occur. Corporal Kikuchi Norimitsu testified that he was told by another unit member that a prisoner "had shown violence and had struck the experimenter with a door handle" and then "jumped out of the cell and ran down the corridor, seized the keys and opened the iron doors and some of the cells. Some of the prisoners managed to jump out but these were only the bold ones. These bold ones were shot."[102]

Seiichi Morimura in his book The Devil's Feast went into some greater detail regarding this escape attempt. Two Russian male prisoners were in a cell with handcuffs on, one of them lay flat on the floor pretending to be sick. This got the attention of a staff member who saw it as an unusual condition. That staff member decided to enter the cell. The Russian lying on the floor suddenly sprang up and knocked the guard down. The two Russians opened their handcuffs, took the keys, and opened some other cells while yelling. Some prisoners, including Russian and Chinese, were frantically roaming the corridors and kept yelling and shouting. One Russian shouted to the members of Unit 731, demanding to be shot rather than used as an experimental object. This Russian was shot to death. One staff member, who was an eyewitness at this escape attempt, recalled: "spiritually we were all lost in front of the 'marutas' who had no freedom and no weapons. At that time we understood in our hearts that justice was not on our side."[103]

Unfortunately for the prisoners of Unit 731, escape was an impossibility. Even if they had managed to escape the quadrangle (itself a heavily fortified building full of staff), they would have had to get over a three-meter-high (9.8 ft) brick wall surrounding the complex, and then across a dry moat filled with electrified wire running around the perimeter of the complex.[104]

Members of Unit 731 were not immune from being subjects of experiments. Yoshio Tamura, an assistant in the Special Team, recalled that Yoshio Sudō, an employee of the first division at Unit 731, became infected with bubonic plague as a result of the production of it. The Special Team was then ordered to vivisect Sudō. Tamura recalled:

Sudō had, a few days previously, been interested in talking about women, but now he was thin as a rake, with many purple spots over his body. A large area of scratches on his chest were bleeding. He painfully cried and breathed with difficulty. I sanitised his whole body with disinfectant. Whenever he moved, a rope around his neck tightened. After Sudō's body was carefully checked [by the surgeon], I handed a scalpel to [the surgeon] who, reversely gripping the scalpel, touched Sudō's stomach skin and sliced downward. Sudō shouted "brute!" and died with this last word.

— Criminal History of Unit 731 of the Japanese Military, pp. 118–119 (1991)

Additionally, Unit 731 Youth Corps member Yoshio Shinozuka testified that his friend junior assistant Mitsuo Hirakawa was vivisected as a result of being accidentally infected with plague.[78]

There are unit members who were known to be interned at the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre and Taiyuan War Criminals Management Centre after the war, who then went on to be repatriated to Japan and founded the Association of Returnees from China and testified about Unit 731 and the crimes perpetrated there.

Some members included:

In April 2018, the National Archives of Japan disclosed a nearly complete list of 3,607 members of Unit 731 to Katsuo Nishiyama, a professor at Shiga University of Medical Science. Nishiyama reportedly intended to publish the list online to encourage further study into the unit.[105]

Previously disclosed members included:

Twelve members were formally tried and sentenced in the Khabarovsk war crimes trials:

| Name | Military position | Unit position[3]: 5 | Unit | Sentenced years in labor camp[3]: 534–535 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kiyoshi Kawashima | Major general of the Medical Service[3]: 10 | Chief of General Division, 1939–1941, Head of Production Division, 1941–1945[106]: 131 | 731 | 25 (served 7) |

| Otozō Yamada | General | Direct controller, 1944–1945[106]: 232 | 731, 100 | 25 (served 7) |

| Ryuji Kajitsuka | Lieutenant general of the Medical Service | Chief of the Medical Administration[106]: 131 | 731 | 25 (served 7) |

| Takaatsu Takahashi | Lieutenant general of the Veterinary Service | Chief of the Veterinary Service | 731 | 25 (died in prison in 1952) |

| Tomio Karasawa | Major of the Medical Service | Chief of a section | 731 | 20 (committed suicide in prison in 1956) |

| Toshihide Nishi | Lieutenant colonel of the Medical Service | Chief of a division | 731 | 18 (served 7) |

| Masao Onoue | Major of the Medical Service | Chief of a branch | 731 | 12 (served 7) |

| Zensaku Hirazakura | Lieutenant | Officer | 100 | 10 (served 7) |

| Kazuo Mitomo | Senior sergeant | Member | 731 | 15 (served 7) |

| Norimitsu Kikuchi | Corporal | Probationer medical orderly | Branch 643 | 2 (served full term) |

| Yuji Kurushima | [none] | Laboratory orderly | Branch 162 | 3 (served full term) |

| Shunji Sato | Major general of the Medical Service | Chief of the Medical Service[106]: 192 | 731, 1644 | 20 (served 7) |

Unit 731 was divided into eight divisions:

Unit 731 had other units underneath it in the chain of command; there were several other units under the auspice of Japan's biological weapons programs. Most or all Units had branch offices, which were also often referred to as "Units." The term Unit 731 can refer to the Harbin complex, or it can refer to the organization and its branches, sub-Units and their branches.

The Unit 731 complex covered six square kilometers (2.3 sq mi) and consisted of more than 150 buildings. The design of the facilities made them hard to destroy by bombing. The complex contained various factories. It had around 4,500 containers to be used to raise fleas, six cauldrons to produce various chemicals, and around 1,800 containers to produce biological agents. Approximately 30 kilograms (66 lb) of bubonic plague bacteria could be produced in a few days. Some of Unit 731's satellite (branch) facilities are still in use by various Chinese industrial companies. A portion has been preserved and is open to visitors as a museum.[108]

Unit 731 had branches in Linkou (Branch 162), Mudanjiang, Hailin (Branch 643), Sunwu (Branch 673) and Hailar (Branch 543).[3]: 60, 84, 124, 310

A medical school and research facility belonging to Unit 731 operated in the Shinjuku District of Tokyo during World War II. In 2006, Toyo Ishii—a nurse who worked at the school during the war—revealed that she had helped bury bodies and pieces of bodies on the school's grounds shortly after Japan's surrender in 1945. In response, in February 2011 the Ministry of Health began to excavate the site.[109]

While Tokyo courts acknowledged in 2002 that Unit 731 has been involved in biological warfare research, as of 2011 the Japanese government had made no official acknowledgment of the atrocities committed against test subjects and rejected the Chinese government's requests for DNA samples to identify human remains (including skulls and bones) found near an army medical school.[110]

As the Second World War started to come to an end, all prisoners within the compound were killed to conceal evidence, and there were no documented survivors.[111] With the coming of the Red Army in August 1945, the unit had to abandon their work in haste. Ministries in Tokyo ordered the destruction of all incriminating materials, including those in Pingfang. Potential witnesses, such as the 300 remaining prisoners, were either gassed or fed poison while the 600 Chinese and Manchurian laborers were shot. Ishii ordered every member of the group to disappear and "take the secret to the grave."[112] Potassium cyanide vials were issued for use in case the remaining personnel were captured. Skeleton crews of Ishii's Japanese troops blew up the compound in the final days of the war to destroy evidence of their activities, but many were sturdy enough to remain somewhat intact.

Former Unit 731 member Hideo Shimizu stated that during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria he was instructed to eliminate evidence by burning the victims in the courtyard, collecting the leftover bones from the area, and then destroying the remains with explosives.[34] While boarding a departing train, he was provided with a cyanide compound and instructed to commit suicide instead of being captured.[34]

Among the individuals in Japan after its 1945 surrender was Lieutenant Colonel Murray Sanders, who arrived in Yokohama via the American ship Sturgess in September 1945. Sanders was a highly regarded microbiologist and a member of America's military center for biological weapons. Sanders' duty was to investigate Japanese biological warfare activity. At the time of his arrival in Japan, he had no knowledge of what Unit 731 was.[68] Until Sanders finally threatened the Japanese with bringing the Soviets into the picture, little information about biological warfare was being shared with the Americans. The Japanese wanted to avoid prosecution under the Soviet legal system, so, the morning after he made his threat, Sanders received a manuscript describing Japan's involvement in biological warfare. Sanders took this information to General Douglas MacArthur, who was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers and responsible for rebuilding Japan during the Allied occupations. MacArthur struck a deal with Japanese informants:[113] he secretly granted immunity to the physicians of Unit 731, including their leader, in exchange for providing exclusive American access to their research on biological warfare and data from human experimentation.[11] American occupation authorities monitored the activities of former unit members, including reading and censoring their mail.[114] The Americans believed that the research data was valuable and did not want other nations, particularly the Soviet Union, to acquire data on biological weapons.[115]

The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal heard only one reference to Japanese experiments with "poisonous serums" on Chinese civilians. This took place in August 1946 and was instigated by Joseph R Massey, assistant to the Chinese prosecutor. The Japanese defense counsel argued that the claim was vague and uncorroborated and it was dismissed by the tribunal president, Sir William Webb, for lack of evidence. The subject was not pursued further by Massey, who was probably unaware of Unit 731's activities. His reference to it at the trial is believed to have been accidental. Later in 1981, one of the last surviving members of the Tokyo Tribunal, Judge Röling, had expressed bitterness in not being made aware of the suppression of evidence of Unit 731 and wrote, "It is a bitter experience for me to be informed now that centrally ordered Japanese war criminality of the most disgusting kind was kept secret from the court by the U.S. government."[116]

American investigations into Japanese war crimes ceased when Japanese scientists began disclosing information on biological warfare. Despite the establishment of their own research program, American scientists faced a significant gap in essential knowledge regarding biological warfare. The potential value to the Americans of Japanese-provided data, encompassing human research subjects, delivery system theories, and successful field trials, was immense. However, historian Sheldon H. Harris concluded that the Japanese data failed to meet American standards, suggesting instead that the findings from the unit were of minor importance at best. Harris characterized the research results from the Japanese camp as disappointing, concurring with the assessment of Murray Sanders, who characterized the experiments as "crude" and "ineffective."[46]

While German physicians were brought to trial and had their crimes publicized, the U.S. concealed information about Japanese biological warfare experiments and secured immunity for the perpetrators. Critics have argued that racism led to the double standard in the American postwar responses to the experiments conducted on different nationalities. Whereas the perpetrators of Unit 731 were exempt from prosecution, the U.S. held a tribunal in Yokohama in 1948 that indicted nine Japanese physician professors and medical students for conducting vivisection upon captured American pilots; two professors were sentenced to death and others to 15–20 years' imprisonment.[117]

Although publicly silent on the issue at the Tokyo Trials, the Soviet Union pursued the case and prosecuted 12 top military leaders and scientists from Unit 731 and its affiliated biological-war prisons Unit 1644 in Nanjing and Unit 100 in Changchun in the Khabarovsk war crimes trials. Among those accused of war crimes, including germ warfare, was General Otozō Yamada, commander-in-chief of the million-man Kwantung Army occupying Manchuria.

The trial of the Japanese perpetrators was held in Khabarovsk in December 1949; a lengthy partial transcript of trial proceedings was published in different languages the following year by the Moscow foreign languages press, including an English-language edition.[118] The lead prosecuting attorney at the Khabarovsk trial was Lev Smirnov, who had been one of the top Soviet prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trials. The Japanese doctors and army commanders who had perpetrated the Unit 731 experiments received sentences from the Khabarovsk court ranging from 2 to 25 years in a Siberian labor camp. The United States refused to acknowledge the trials, branding them communist propaganda.[119] The sentences doled out to the Japanese perpetrators were unusually lenient by Soviet standards, and all but two of the defendants returned to Japan by the 1950s (with one prisoner dying in prison and the other committing suicide inside his cell).

In addition to the accusations of propaganda, the US also asserted that the trials were to only serve as a distraction from the Soviet treatment of several hundred thousand Japanese prisoners of war; meanwhile, the USSR asserted that the US had given the Japanese diplomatic leniency in exchange for information about their human experimentation. However, former Unit 731 members had also passed information about their biological experimentation to the Soviet government in exchange for judicial leniency.[120] This was evidenced by the Soviet Union building a biological weapons facility in Sverdlovsk using documentation captured from Unit 731 in Manchuria.[12]

As above, during the United States occupation of Japan, the members of Unit 731 and the members of other experimental units were allowed to go free. On 6 May 1947, Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, wrote to Washington in order to inform it that "additional data, possibly some statements from Ishii, can probably be obtained by informing Japanese involved that information will be retained in intelligence channels and will not be employed as war crimes evidence".[11]

According to an investigation by The Guardian, after the end of the war, under the pretense of vaccine development, former members of Unit 731 conducted human experiments on Japanese prisoners, babies and mental patients, with secret funding from the U.S. Government.[121] One graduate of Unit 1644, Masami Kitaoka, continued to perform experiments on unwilling Japanese subjects from 1947 to 1956. He performed his experiments while he was working for Japan's National Institute of Health Sciences. He infected prisoners with rickettsia and infected mentally-ill patients with typhus.[122] As the chief of the unit, Shiro Ishii was granted immunity from prosecution for war crimes by the American occupation authorities, because he had provided human experimentation research materials to them. From 1948 to 1958, less than five percent of the documents were transferred onto microfilm and stored in the US National Archives before they were shipped back to Japan.[123]

Japanese discussions of Unit 731's activity began in the 1950s, after the end of the American occupation of Japan. In 1952, an infant girl at Nagoya City Pediatric Hospital died after being infected with E coli bacteria; the incident was publicly tied to former Unit 731 scientists.[124] Later in that decade, journalists suspected that the murders attributed by the government to Sadamichi Hirasawa were actually carried out by members of Unit 731. In 1958, Japanese author Shūsaku Endō published the book The Sea and Poison about human experimentation in Fukuoka, which is thought to have been based on a real incident.

In 1950, former members of Unit 731 including Masaji Kitano founded the blood bank and pharmaceutical company Green Cross, for which Murray Sanders also served as a consultant. The company became the target of a scandal in the 1980s after up to 3,000 Japanese contracted HIV through the distribution and use of its blood products, which the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency had deemed unsafe.[125][126]

The author Seiichi Morimura published The Devil's Gluttony (悪魔の飽食) in 1981, followed by The Devil's Gluttony: A Sequel in 1983. These books purported to reveal the "true" operations of Unit 731, but falsely attributed unrelated photos to the Unit, which raised questions about their accuracy.[127][128] Also in 1981, the first direct testimony of human vivisection in China was given by Ken Yuasa. Since then, much more in depth testimony has been given in Japan. The 2001 documentary Japanese Devils largely consists of interviews with fourteen Unit 731 staff members taken prisoner by China and later released.[129] Prince Mikasa, who was the younger brother of Hirohito, toured the Unit 731 headquarters in China, and wrote in his memoir that he watched films showing how Chinese prisoners were "made to march on the plains of Manchuria for poison gas experiments on humans."[1] Hideki Tojo, who later became Prime Minister in 1941, was also shown films of the experiments, which he described as "unpleasant."[130]

Despite conducting scientific experiments, Unit 731 faced scrutiny regarding the usefulness of the data produced from these experiments.[46] Japanese biological warfare operations were by far the largest during WWII, and "possibly with more people and resources than the BW producing nations of France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and the Soviet Union combined, between the world wars.[131] Despite the apparent success, Unit 731 lacked adequate scientific and engineering foundations to further maximize its effectiveness.[132][133] Harris concluded that US scientists generally wanted to acquire it due to the concept of forbidden fruit, believing that lawful and ethical prohibitions could affect the outcomes of their research.[134]

Historian Till Winfried Bärnighausen criticized the overall lack of scientific rigor in many of Unit 731's experiments, but he noted some exceptions. He pointed to the mustard gas, freezing, and tuberculosis experiments as having a reliable and valid data collection process, suggesting they were conducted with greater rigor.[46]

In 1969, Ikeda Naeo, a physician associated with Unit 731, published his own research on epidemic hemorrhagic fever (EHF). His paper documented experiments conducted at a military hospital on the China-Soviet border in January 1942. These experiments, involving infections on humans, confirmed the transmission of EHF by lice and fleas to local populations, resulting in a deaths among those infected. Despite the explicit admission of conducting experiments on humans with fatal pathogenic inoculations, Ikeda's report passed peer review and was published in a Japanese scholarly journal. The acceptance of this research by Ikeda underscored the widespread acknowledgment within the Japanese medical community of the human experiments conducted at Unit 731.[135]

During the war, Yoshimura Hisato conducted research at Unit 731 in China focusing on low-temperature physiology, particularly studying the mechanisms involved in frostbite. Following the war, he established the Japanese Society of Biometeorology. His research in China marked the inception of his exploration into the relationship between physiology and environmental stress.[135]

Most researchers at Unit 731 did not engage in a concerted effort to conceal the experiments they participated in. While they refrained from publicly acknowledging their crimes, they did share various details within their medical circles. Consequently, especially regarding research on EHF and frostbite, it has been relatively straightforward to ascertain who conducted which type of human experiments. Given that nearly all members of the Japanese medical community were aware of the human experiments conducted at Unit 731, researchers from the Unit were able to later publish their work in medical papers. Even after the war, reports were disseminated unmistakably detailing the results of experiments on humans, and accounts of the Unit were documented in medical journals. This indicates widespread awareness within the Japanese medical community regarding the experiments carried out at Unit 731.[135]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some scientists called for experimental data from Unit 731 to be publicly released to the international medical community because the data available on human-pathogen interactions could have helped epidemiologists with pandemic control.[136] The information has been withheld by both the US and Japanese government.

In 1983, the Japanese Ministry of Education asked Japanese historian Saburō Ienaga to remove a reference from one of his textbooks that stated Unit 731 conducted experiments on thousands of Chinese. The ministry alleged that no academic research supported the claim. In 1984, Japanese historian Tsuneishi Keiichi translated and published over 4,000 pages of U.S. documents on Japanese biological warfare. The ministry backed down after new studies were published in Japan and important evidence surfaced in the United States.[137]

Japanese history textbooks usually contain references to Unit 731, but the textbooks do not provide specific details about the activities conducted at the facility.[138][139] Saburō Ienaga's New History of Japan included a detailed description, based on officers' testimony. The Ministry for Education attempted to remove this passage from his textbook before it was taught in public schools, on the basis that the testimony was insufficient. The Supreme Court of Japan ruled in 1997 that the testimony was indeed sufficient and that requiring it to be removed was an illegal violation of freedom of speech.[140]

In 1997, international lawyer Kōnen Tsuchiya filed a class action suit against the Japanese government, demanding reparations for the actions of Unit 731, using evidence filed by Professor Makoto Ueda of Rikkyo University. All levels of the Japanese court system found the suit baseless. No findings of fact were made about the existence of human experimentation. In August 2002, the Tokyo district court ruled for the first time that Japan had engaged in biological warfare. Presiding judge Koji Iwata ruled that Unit 731, on the orders of the Imperial Japanese Army headquarters, used bacteriological weapons on Chinese civilians between 1940 and 1942, spreading diseases, including plague and typhoid, in the cities of Quzhou, Ningbo, and Changde. He rejected victims' compensation claims on the grounds that they had already been settled by international peace treaties.[141]

In October 2003, a member of Japan's House of Representatives filed an inquiry. Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi responded that the Japanese government did not then possess any records related to Unit 731, but recognized the gravity of the matter and would publicize any records located in the future.[142] In April 2018, the National Archives of Japan released the names of 3,607 members of Unit 731, in response to a request by Professor Katsuo Nishiyama of the Shiga University of Medical Science.[143][144]

After World War II, the Office of Special Investigations created a watchlist of suspected Axis collaborators and persecutors who are banned from entering the United States. While they have added over 60,000 names to the watchlist, they have only been able to identify under 100 Japanese participants. In a 1998 correspondence letter between the DOJ and Rabbi Abraham Cooper, Eli Rosenbaum, director of OSI, stated that this was due to two factors:

Unit 731 was a special division of the Japanese Army, a scientific and military elite. It had a huge budget specially authorised by the Emperor, to develop weapons of mass destruction that would win the war for Japan. America and Germany had their nuclear arms race. Japan put its faith in germs. Anita McNaught reports.