Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| United Nations initiatives |

| International Treaties |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Countries |

| Category |

Traditional knowledge (TK), indigenous knowledge (IK),[1] folk knowledge, and local knowledge generally refers to knowledge systems embedded in the cultural traditions of regional, indigenous, or local communities.[2]

Traditional knowledge includes types of knowledge about traditional technologies of areas such as subsistence (e.g. tools and techniques for hunting or agriculture), midwifery, ethnobotany and ecological knowledge, traditional medicine, celestial navigation, craft skills, ethnoastronomy, climate, and others. These systems of knowledge are generally based on accumulations of empirical observation of and interaction with the environment, transmitted across generations.[3][4]

In many cases, traditional knowledge has been passed on for generations from person to person, as an oral tradition. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the United Nations (UN) include traditional cultural expressions (TCE) in their respective definitions of indigenous knowledge. Traditional knowledge systems and cultural expressions exist in the forms of culture, stories, legends, folklore, rituals, songs, and laws,[5][6][7] languages, songlines, dance, games, mythology, designs, visual art and architecture.[8]

A report of the International Council for Science (ICSU) Study Group on Science and Traditional Knowledge characterises traditional knowledge as:[9]

a cumulative body of knowledge, know-how, practices and representations maintained and developed by peoples with extended histories of interaction with the natural environment. These sophisticated sets of understandings, interpretations and meanings are part and parcel of a cultural complex that encompasses language, naming and classification systems, resource use practices, ritual, spirituality and worldview.

Traditional knowledge typically distinguishes one community from another. In some communities, traditional knowledge takes on personal and spiritual meanings. Traditional knowledge can also reflect a community's interests. Some communities depend on their traditional knowledge for survival. Traditional knowledge regarding the environment, such as taboos, proverbs and cosmological knowledge systems, may provide a conservation ethos for biodiversity preservation.[citation needed] This is particularly true of traditional environmental knowledge, which refers to a "particular form of place-based knowledge of the diversity and interactions among plant and animal species, landforms, watercourses, and other qualities of the biophysical environment in a given place".[10] As an example of a society with a wealth of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), the South American Kayapo people, have developed an extensive classification system of ecological zones of the Amazonian tropical savannah (i.e., campo / cerrado) to better manage the land.[11]

Some social scientists conceptualise knowledge within a naturalistic framework and emphasize the gradation of recent knowledge into knowledge acquired over many generations. These accounts use terms like adaptively acquired knowledge, socially constructed knowledge, and other terms that emphasize the social aspects of knowledge.[12] Local knowledge and traditional knowledge may be thought of as distinguished by the length of time they have existed, from decades to centuries or millennia.

On the other hand, indigenous and local communities themselves may perceive traditional knowledge very differently. The knowledge of indigenous and local communities is often embedded in a cosmology, and any distinction between "intangible" knowledge and physical things can become blurred. Indigenous peoples often say that indigenous knowledge is holistic, and cannot be meaningfully separated from the lands and resources available to them. Traditional knowledge in such cosmologies is inextricably bound to ancestors, and ancestral lands.[citation needed] Chamberlin (2003) writes of a Gitksan elder from British Columbia confronted by a government land-claim: "If this is your land," he asked, "where are your stories?"[13]

Indigenous and local communities often do not have strong traditions of ownership over knowledge that resemble the modern forms of private ownership. Many have clear traditions of custodianship over knowledge, and customary law may guide who may use different kinds of knowledge at particular times and places, and specify obligations that accompany the use of knowledge. For example, a hunter might be permitted to kill an animal only to feed the community, and not to feed himself. From an indigenous perspective, misappropriation and misuse of knowledge may be offensive to traditions, and may have spiritual and physical repercussions in indigenous cosmological systems. Consequently, indigenous and local communities argue that others' use of their traditional knowledge warrants respect and sensitivity. Critics of traditional knowledge, however, see such demands for "respect" as an attempt to prevent unsubstantiated beliefs from being subjected to the same scrutiny as other knowledge-claims.[citation needed] This has particular significance for environmental management because the spiritual component of "traditional knowledge" can justify any activity, including the unsustainable harvesting of resources.

Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCE) are both types of Indigenous Knowledge (IK), according to the definitions and terminology used in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).[8]

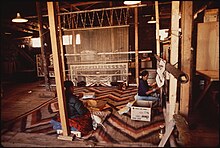

The phrase "traditional cultural expressions" is used by WIPO to refer to "any form of artistic and literary expression in which traditional culture and knowledge are embodied. They are transmitted from one generation to the next, and include handmade textiles, paintings, stories, legends, ceremonies, music, songs, rhythms and dance."[14]

WIPO negotiates international legal protection of traditional cultural expressions through the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge, and Folklore (IGC).[15] During the committee's sessions, representatives of indigenous and local communities host panels relating to the preservation of traditional knowledge.[16]

Leading international authority on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, Australian lawyer Terri Janke, says that within Australian Indigenous communities (comprising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples), "the use of the word 'traditional' tends not to be preferred as it implies that Indigenous culture is locked in time".[8]

International attention has turned to intellectual property laws to preserve, protect, and promote traditional knowledge. In 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognized the value of traditional knowledge in protecting species, ecosystems and landscapes, and incorporated language regulating access to it and its use (discussed below). It was soon urged that implementing these provisions would require revision[how?] of international intellectual property agreements.[citation needed]

This became even more pressing with the adoption of the World Trade Organization Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), which established rules for creating and protecting intellectual property that could be interpreted to conflict with the agreements made under the CBD.[17] In response, the states who had ratified the CBD requested the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) to investigate the relationship between intellectual property rights, biodiversity and traditional knowledge. WIPO began this work with a fact-finding mission in 1999. Considering the issues involved with biodiversity and the broader issues in TRIPs (involving all forms of cultural expressions, not just those associated with biodiversity – including traditional designs, music, songs, stories, etc.), WIPO established the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC-GRTKF). WIPO Lex provides support for collections of laws concerning Traditional Knowledge.[18]

The period of the early 1990s to the Millennium was also characterized by the rapid rise in global civil society. The high-level Brundtland Report (1987) recommended a change in development policy that allowed for direct community participation and respected local rights and aspirations. Indigenous peoples and others had successfully petitioned the United Nations to establish a Working Group on Indigenous Populations that made two early surveys on treaty rights and land rights. These led to a greater public and governmental recognition of indigenous land and resource rights, and the need to address the issue of collective human rights, as distinct from the individual rights of existing human rights law.

The collective human rights of indigenous and local communities has been increasingly recognized – such as in the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 (1989) and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007). The Rio Declaration (1992), endorsed by the presidents and ministers of the majority of the countries of the world, recognized indigenous and local communities as distinct groups with special concerns that should be addressed by states.

Initial concern was over the territorial rights and traditional resource rights of these communities. Indigenous peoples soon showed concern for the misappropriation and misuse of their "intangible" knowledge and cultural heritage. Indigenous peoples and local communities have resisted, among other things: the use of traditional symbols and designs as mascots, derivative arts and crafts; the use or modification of traditional songs; the patenting of traditional uses of medicinal plants; and the copyrighting and distribution of traditional stories.

Indigenous peoples and local communities have sought to prevent the patenting of traditional knowledge and resources where they have not given express consent. They have sought for greater protection and control over traditional knowledge and resources. Certain communities have also sought to ensure that their traditional knowledge is used equitably - according to restrictions set by their traditions, or requiring benefit sharing for its use according to benefits which they define.

Three broad approaches to protect traditional knowledge have been developed. The first emphasizes protecting traditional knowledge as a form of cultural heritage. The second looks at protection of traditional knowledge as a collective human right. The third, taken by the WTO and WIPO, investigates the use of existing or novel sui generis measures to protect traditional knowledge.

Currently, only a few nations offer explicit sui generis protection for traditional knowledge. However, a number of countries are still undecided as to whether law should give traditional knowledge deference. Indigenous peoples have shown ambivalence about the intellectual property approach. Some have been willing to investigate how existing intellectual property mechanisms (primarily: patents, copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets) can protect traditional knowledge. Others believe that an intellectual property approach may work, but will require more radical and novel forms of intellectual property law ("sui generis rights"). Others believe that the intellectual property system uses concepts and terms that are incompatible with traditional cultural concepts, and favors the commercialization of their traditions, which they generally resist. Many have argued that the form of protection should refer to collective human rights to protect their distinct identities, religions and cultural heritage.

Literary and artistic works based upon, derived from or inspired by traditional culture or folklore may incorporate new elements or expressions. Hence these works may be "new" works with a living and identifiable creator, or creators. Such contemporary works may include a new interpretation, arrangement, adaptation or collection of pre-existing cultural heritage that is in the public domain. Traditional culture or folklore may also be "repackaged" in digital formats, or restoration and colorization. Contemporary and tradition based expressions and works of traditional culture are generally protected under existing copyright law, a form of intellectual property law, as they are sufficiently original to be regarded as "new" upon publication. Copyright protection is normally temporary. When a work has existed for a long enough period (often for the rest of the author's life plus an additional 50 to 70 years), the legal ability of the creator to prevent other people from reprinting, modifying, or using the property lapses, and the work is said to enter the public domain.[19] Copyright protection also does not extend to folk songs and other works that developed over time, with no identifiable creators.

Having an idea, story, or other work legally protected only for a limited period of time is not accepted by some indigenous peoples. On this point the Tulalip Tribes of Washington state has commented that "open sharing does not automatically confer a right to use the knowledge (of indigenous people)... traditional cultural expressions are not in the public domain because indigenous peoples have failed to take the steps necessary to protect the knowledge in the Western intellectual property system, but from a failure of governments and citizens to recognise and respect the customary laws regulating their use".[19] Equally, however, the idea of restricting the use of publicly available information without clear notice and justification is regarded by many in developed nations as unethical as well as impractical.[20]

Indigenous intellectual property[2] is an umbrella legal term used in national and international forums to identify indigenous peoples' special rights to claim (from within their own laws) all that their indigenous groups know now, have known, or will know.[21] It is a concept that has developed out of a predominantly western legal tradition, and has most recently been promoted by the World Intellectual Property Organization, as part of a more general United Nations push[22] to see the diverse wealth of the world's indigenous, intangible cultural heritage better valued and better protected against probable, ongoing misappropriation and misuse.[23]

In the lead-up to and during the United Nations International Year for the World's Indigenous People (1993),[24] and then during the following UN Decade of the World's Indigenous People (1995–2004),[22] a number of conferences of both indigenous and non-indigenous specialists were held in different parts of the world, resulting in a number of declarations and statements identifying, explaining, refining, and defining "indigenous intellectual property".[25]

Article 27. 3(b) of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) sets out certain conditions under which certain biological materials or intellectual innovations may be excluded from patenting. The Article also contains a requirement that Article 27 be reviewed. In the TRIPs-related Doha Declaration of 2001, Paragraph 19 expanded the review to a review of Article 27 and the rest of the TRIPs agreement to include the relationship between the TRIPS Agreement and the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the protection of traditional knowledge and folklore.[17]

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), signed at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1993, was the first international environmental convention to develop measures for the use and protection of traditional knowledge, related to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.[26] By 2006, 188 had ratified the Convention and agreed to be bound by its provisions, the largest number of nations to accede to any existing treaty (the United States is one of the few countries that has signed, but not ratified, the CBD). Significant provisions include:

Article 8. In-situ Conservation

Each Contracting Party shall, as far as possible and as appropriate:

(a)...

(j) Subject to its national legislation, respect, preserve and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and promote their wider application with the approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of such knowledge, innovations and practices...

Article 10. Sustainable Use of Components of Biological Diversity

Each Contracting Party shall, as far as possible and as appropriate:

(a)...

(c) Protect and encourage customary use of biological resources in accordance with traditional cultural practices that are compatible with conservation or sustainable use requirements

The interpretation of these provisions has been elaborated through decisions by the parties (ratifiers of the Convention) (see the Convention on Biological Diversity Handbook, available free in digital format from the Secretariat). Nevertheless, the provisions regarding Access and Benefit Sharing contained in the Convention on Biological Diversity never achieved consensus and soon the authority over these questions fell back to WIPO.[27]

At the Convention on Biological Diversity meeting, in Buenos Aires, in 1996, emphasis was put on local knowledge. Key players, such as local communities and indigenous peoples, should be recognized by States, and have their sovereignty recognised over the biodiversity of their territories, so that they can continue protecting it.[28]

The parties to the Convention set a 2010 target to negotiate an international legally binding regime on access and benefit sharing (ABS) at the Eighth meeting (COP8), 20–31 March 2006 in Curitiba, Brazil. This target was met in October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan, by conclusion of the Nagoya Protocol to the CBD. The agreement is now open for ratification, and will come into force when 50 signatories have ratified it. It entered into force on 12 October 2014. As of August 2020, 128 nations ratified the Nagoya Protocol.[29] The Protocol treats of inter-governmental obligations related to genetic resources, and includes measures related to the rights of indigenous and local communities to control access to and derive benefits from the use of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge.

In September 2020, the government of Queensland introduced the Biodiscovery and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2020, which introduced protections for accessing and using First Nations peoples' traditional knowledge in biodiscovery.[30]

In 2001, the Government of India set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) as repository of 1200 formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as Ayurveda, Unani and Siddha and 1500 Yoga postures (asanas), translated into five languages – English, German, French, Spanish and Japanese.[citation needed] India has also signed agreements with the European Patent Office (EPO), United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to prevent the grant of invalid patents by giving patent examiners at International Patent Offices access to the TKDL database for patent search and examination.[citation needed]

Some of the legislative measures to protect TK are The Biological Diversity Act (2002), The Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers' Rights Act (2001) and The Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration And Protection) Act, 1999.

The Intellectual Property Rights Policy for Kerala released in 2008[31] proposes adoption of the concepts 'knowledge commons' and 'commons licence' for the protection of traditional knowledge. The policy, largely created by Prabhat Patnaik and R.S. Praveen Raj, seeks to put all traditional knowledge into the realm of "knowledge commons", distinguishing this from the public domain. Raj has argued that TKDL cannot at the same time be kept confidential and treated as prior art.[32][33]

In 2016, Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament from Thiruvananthapuram introduced a Private Bill (the Protection of Traditional Knowledge Bill, 2016[34]) codifying the "protection, preservation and promotion" of traditional knowledge system in India. However the bill was criticised for failing to address the real concern of traditional knowledge.[35][further explanation needed]

How, if at all, to include indigenous knowledge in education and in relation to science has been controversial. It has been argued that indigenous knowledge can be complementary to science and includes empirical information, even encoded in myths, and that it holds equal educational value to science like the arts and humanities.[4] Proponents also argue that its inclusion combats disillusionment among indigenous groups with the education system and helps to preserve their cultural identity.[36][37] Studies indicate that if the introduction of TK into educational curriculums is to succeed, it would need to taught from the perspective of the relevant worldview, involve community participation, and have a bridge built between the national/dominant language and the indigenous one.[37]

Efforts to include it in education have been criticized on the grounds that it is inseparable from spiritual and religious beliefs; that it is not possible to reconcile contradictions between science and TK; that time spent on it comes at the cost of time delivering curricula that meets international academic standards; that policies granting science and indigenous knowledge equal status are based on relativism and inhibit science from questioning claims made by indigenous knowledge systems; and that many proponents of indigenous knowledge engage in ideological antiscience rhetoric.[38]

In New Zealand, an indigenous vitalist concept (mauri) was introduced into the national chemistry curriculum, and the government ignored the objections of science teachers citing an 'equal status' policy. It was later removed from exam objectives after 18 months of controversy, though it still appeared in some materials afterwards.[39]

However, there is some agreement that they all refer to: "a people's (1) shared system of knowledge or other expression about the environment and ecosystem relationships that is (2) developed through direct experience within a specific physical setting, and (3) is transmitted between or among generations"

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)