Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Chinese units of measurement | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A traditional Chinese scale | |||||||||

| Chinese | 市制 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | market system | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 市用制 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | market-use system | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Chinese units of measurement, known in Chinese as the shìzhì ("market system"), are the traditional units of measurement of the Han Chinese. Although Chinese numerals have been decimal (base-10) since the Shang, several Chinese measures use hexadecimal (base-16).[citation needed] Local applications have varied, but the Chinese dynasties usually proclaimed standard measurements and recorded their predecessor's systems in their histories.

In the present day, the People's Republic of China maintains some customary units based upon the market units but standardized to round values in the metric system, for example the common jin or catty of exactly 500 g. The Chinese name for most metric units is based on that of the closest traditional unit; when confusion might arise, the word "market" (市, shì) is used to specify the traditional unit and "common" or "public" (公, gōng) is used for the metric value. Taiwan, like Korea, saw its traditional units standardized to Japanese values and their conversion to a metric basis, such as the Taiwanese ping of about 3.306 m2 based on the square ken. The Hong Kong SAR continues to use its traditional units, now legally defined based on a local equation with metric units. For instance, the Hong Kong catty is precisely 604.78982 g.

Note: The names lí (釐 or 厘) and fēn (分) for small units are the same for length, area, and mass; however, they refer to different kinds of measurements.

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

According to the Liji, the legendary Yellow Emperor created the first measurement units. The Xiao Erya and the Kongzi Jiayu state that length units were derived from the human body. According to the Records of the Grand Historian, these human body units caused inconsistency, and Yu the Great, another legendary figure, unified the length measurements. Rulers with decimal units have been unearthed from Shang dynasty tombs.

In the Zhou dynasty, the king conferred nobles with powers of the state and the measurement units began to be inconsistent from state to state. After the Warring States period, Qin Shi Huang unified China, and later standardized measurement units. In the Han dynasty, these measurements were still being used, and were documented systematically in the Book of Han.

Astronomical instruments show little change of the length of chi in the following centuries, since the calendar needed to be consistent. It was not until the introduction of decimal units in the Ming dynasty that the traditional system was revised.

On 7 January 1915, the Beiyang government promulgated a measurement law to use not only metric system as the standard but also a set of Chinese-style measurement based directly on the Qing dynasty definitions (营造尺库平制).[1]

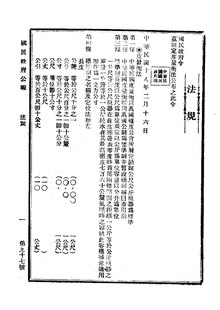

On 16 February 1929, the Nationalist government adopted and promulgated The Weights and Measures Act[2] to adopt the metric system as the official standard and to limit the newer Chinese units of measurement (Chinese: 市用制; pinyin: shìyòngzhì; lit. 'market-use system') to private sales and trade in Article 11, effective on 1 January 1930. These newer "market" units are based on rounded metric numbers.[3]

The Government of the People's Republic of China continued using the market system along with metric system, as decreed by the State Council of the People's Republic of China on 25 June 1959, but 1 catty being 500 grams, would become divided into 10 (new) taels, instead of 16 (old) taels, to be converted from province to province, while exempting Chinese prescription drugs from the conversion to prevent errors.[4]

On 27 February 1984, the State Council of the People's Republic of China decreed the market system to remain acceptable until the end of 1990 and ordered the transition to the national legal measures by that time, but farmland measures would be exempt from this mandatory metrication until further investigation and study.[5]

In 1976 the Hong Kong Metrication Ordinance allowed a gradual replacement of the system in favor of the International System of Units (SI) metric system.[6] The Weights and Measures Ordinance defines the metric, Imperial, and Chinese units.[7] As of 2012, all three systems are legal for trade and are in widespread use.

On 24 August 1992, Macau published Law No. 14/92/M to order that Chinese units of measurement similar to those used in Hong Kong, Imperial units, and United States customary units would be permissible for five years since the effective date of the Law, 1 January 1993, on the condition of indicating the corresponding SI values, then for three more years thereafter, Chinese, Imperial, and US units would be permissible as secondary to the SI.[8]

Traditional units of length include the chi (尺), bu (步), and li (里). The precise length of these units, and the ratios between these units, has varied over time. 1 bu has consisted of either 5 or 6 chi, while 1 li has consisted of 300 or 360 bu.

| dynasty | chi | bu | li | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| = 5 chi | = 6 chi | = 300 bu | = 360 bu | ||

| Shang (c. 1600 – c. 1045 BC) | 0.1675 | 1.0050 | 301.50 | ||

| 0.1690 | 1.0140 | 304.20 | |||

| Western Zhou (c. 1045–771 BC) | 0.1990 | 1.1940 | 358.20 | ||

| Eastern Zhou (c. 771–256 BC) | 0.2200 | 1.3200 | 396.00 | ||

| 0.2270 | 1.3620 | 408.60 | |||

| 0.2310 | 1.3860 | 415.80 | |||

| Qin (c. 221–206 BC) | 0.2260 | 1.3560 | 406.80[10] 415.80[11][12] | ||

| Han (c. 202 BC–9 AD; 25–220 AD) | 0.2300 | 1.3800 | 414.00 | ||

| 0.2381 | 1.4286 | 415.80[13] 415.80[11][12] 428.58 [10] | |||

| Wei - Sui (c. 220–266 AD; 581 to 618 AD) | 0.2550 | 1.5300 | 459.00 | ||

| Tang (c. 618–690 AD; 705–907 AD) | 0.2465 | 1.2325 | 369.75 | 443.70 | |

| 0.2955 | 1.4775 | 443.25 | 531.90 | ||

| Song (c. 960–1279 AD) | 0.2700 | 1.3500 | 405.00 | 486.00 | |

| Northern Song (c. 960–1127 AD) | 0.3080 | 1.5400 | 462.00 | 554.40 | |

| Ming (c. 1368–1644 AD) | 0.3008–0.3190 | 1.5040–1.5950 | 451.20–478.50 | 541.44–574.20 | |

| Qing (c. 1636–1912 AD) | 0.3080–0.3352 | 1.5400–1.6760 | 462.00–503.89 | 554.40–603.46 | |

All "metric values" given in the tables are exact unless otherwise specified by the approximation sign '~'.

Certain units are also listed at List of Chinese classifiers → Measurement units.

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄10000 | 32 μm | 0.00126 in | |

| lí | 釐 (T) or 厘 (S) | 1⁄1000 | 0.32 mm | 0.0126 in | |

| fēn | 分 | 1⁄100 | 3.2 mm | 0.126 in | |

| cùn | 寸 | 1⁄10 | 32 mm | 1.26 in | Chinese inch |

| chǐ | 尺 | 1 | 0.32 m | 12.6 in | Chinese foot |

| bù | 步 | 5 | 1.6 m | 5.2 ft | Chinese pace |

| zhàng | 丈 | 10 | 3.2 m | 3.50 yd | Chinese yard |

| yǐn | 引 | 100 | 32 m | 35.0 yd | |

| lǐ | 里 | 1800 | 576 m | 630 yd | Chinese mile, this li is not the small li above, which has a different character and tone |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄10 000 | 33+1⁄3 μm | 0.00131 in | Chinese mil |

| lí | 釐 (T) or 厘 (S) | 1⁄1000 | 1⁄3 mm | 0.0131 in | Chinese calibre |

| fēn | 市分 | 1⁄100 | 3+1⁄3 mm | 0.1312 in | Chinese line |

| cùn | 市寸 | 1⁄10 | 3+1⁄3 cm | 1.312 in | Chinese inch |

| chǐ | 市尺 | 1 | 33+1⁄3 cm | 13.12 in | Chinese foot |

| zhàng | 市丈 | 10 | 3+1⁄3 m | 3.645 yd | Chinese yard |

| yǐn | 引 | 100 | 33+1⁄3 m | 36.45 yd | Chinese chain |

| lǐ | 市里 | 1500 | 500 m | 546.8 yd | Chinese mile, this li is not the small li above, which has a different character and tone |

The Chinese word for metre is 米 mǐ; this can take the Chinese standard SI prefixes (for "kilo-", "centi-", etc.). A kilometre, however, may also be called 公里 gōnglǐ, i.e. a metric lǐ.

In the engineering field, traditional units are rounded up to metric units. For example, the Chinese word 絲 (T) or 丝 (S) sī is used to express 0.01 mm.

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hū | 忽 | 1⁄1000000 | 1 μm | Authorized name: 微米 | |

| sī | 絲 (T) or 丝 (S) | 1⁄100000 | 10 μm | Authorized name: 忽米 | |

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄10000 | 100 μm | Authorized name: 絲米 (T) or 丝米 (S) | |

| lí | 釐 (T) or 厘 (S) | 1⁄1000 | 1 mm | Authorized name: 毫米 | |

| fēn | 公分 | 1⁄100 | 10 mm | Authorized name: 釐米(T) or 厘米(S) | |

| cùn | 公寸 | 1⁄10 | 100 mm | Authorized name: 分米 | |

| chǐ | 公尺 | 1 | 1 m | Authorized name: 米 | |

| Zhàng | 公丈 | 10 | 10 m | Authorized name: 十米 | |

| yǐn | 公引 | 100 | 100 m | Authorized name: 百米 | |

| lǐ | 公里 | 1000 | 1000 m | this li is not the small li above, which has a different character and tone |

| Jyutping | Character | English | Portuguese | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fan1 | 分 | fan | condorim | 1⁄100 | 3.71475 mm | 0.1463 in | |

| cyun3 | 寸 | tsun | ponto | 1⁄10 | 37.1475 mm | 1.463 in | Hong Kong and Macau inch |

| cek3 | 尺 | chek | côvado | 1 | 371.475 mm | 1.219 ft | Hong Kong and Macau foot |

These correspond to the measures listed simply as "China" in The Measures, Weights, & Moneys of All Nations [14]

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄1000 | 0.6144 m2 | 0.7348 sq yd | |

| lí | 釐 (T) or 厘 (S) | 1⁄100 | 6.144 m2 | 7.348 sq yd | |

| fēn | 分 | 1⁄10 | 61.44 m2 | 73.48 sq yd | |

| mǔ | 畝 (T) or 亩 (S) | 1 | 614.4 m2 | 734.82 sq yd | Chinese acre, or 60 square zhang |

| qǐng | 頃 (T) or 顷 (S) | 100 | 6.144 ha | 15.18 acre | Chinese hide |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fāng cùn | 方寸 | 1⁄100 | 10.24 cm2 | 1.587 sq in | square cun |

| fāng chǐ | 方尺 | 1 | 0.1024 m2 | 1.102 sq ft | square chi |

| fāng zhàng | 方丈 | 100 | 10.24 m2 | 110.2 sq ft | square zhang |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄1000 | 2⁄3 m2 | 7.18 sq ft | |

| lí | 釐 (T) or 厘 (S) | 1⁄100 | 6+2⁄3 m2 | 7.973 sq yd | |

| fēn | 市分 | 1⁄10 | 66+2⁄3 m2 | 79.73 sq yd | |

| mǔ | 畝 (T) or 亩 (S) | 1 | 666+2⁄3 m2 | 797.3 sq yd 0.1647 acre |

Chinese acre 6000 square chi per Article 5 of the 1930 Law (六千平方尺定為一畝) 60 square zhang 1/15 of a hectare |

| qǐng | 頃 (T) or 顷 (S) | 100 | 6+2⁄3 ha | 16.47 acre | Chinese hide |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fāng cùn | 方寸 | 1⁄100 | 11+1⁄9 cm2 | 1.722 sq in | square cun |

| fāng chǐ | 方尺 | 1 | 1⁄9 m2 | 172.2 sq in 1.196 sq ft |

square chi |

| fāng zhàng | 方丈 | 100 | 11+1⁄9 m2 | 119.6 sq ft 13.29 sq yd |

square zhang |

Metric and other standard length units can be squared by the addition of the prefix 平方 píngfāng. For example, a square kilometre is 平方公里 píngfāng gōnglǐ.

| Jyutping | Portuguese | Character | Relative value | Relation to the Traditional Chinese Units (Macau) | Metric value | Imperial value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cek3 | côvado | 尺 | 1⁄6000 | 1⁄25鋪 | 0.1269 m2 | 1.366 sq ft |

| pou3 | 鋪 | 1⁄240 | 1⁄4丈 | 3.1725 m2 | 34.15 sq ft 3.794 sq yd | |

| zoeng6 | braça | 丈 | 1⁄60 | 1⁄6分 | 12.69 m2 | 136.6 sq ft 15.18 sq yd |

| fan1 | condorim | 分 | 1⁄10 | 1⁄10畝 | 76.14 m2 | 91.06 sq yd |

| mau5 | maz | 畝 (T) or 亩 (S) | 1 | None | 761.4 m2 | 910.6 sq yd |

These units are used to measure cereal grains, among other things. In imperial times, the physical standard for these was the jialiang.

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | US value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sháo | 勺 | 1⁄100 | 10.354688 mL | 0.3501 fl oz | 0.3644 fl oz | |

| gě | 合 | 1⁄10 | 103.54688 mL | 3.501 fl oz | 3.644 fl oz | |

| shēng | 升 | 1 | 1.0354688 L | 2.188 pt | 1.822 pt | |

| dǒu | 斗 | 10 | 10.354688 L | 2.735 gal | 2.278 gal | |

| hú | 斛 | 50 | 51.77344 L | 13.68 gal | 11.39 gal | |

| dàn | 石 | 100 | 103.54688 L | 27.35 gal | 22.78 gal |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | US value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cuō | 撮 | 1⁄1000 | 1 mL | 0.0338 fl oz | 0.0352 fl oz | millilitre |

| sháo | 勺 | 1⁄100 | 10 mL | 0.3381 fl oz | 0.3520 fl oz | centilitre |

| gě | 合 | 1⁄10 | 100 mL | 3.381 fl oz | 3.520 fl oz | decilitre |

| shēng | 市升 | 1 | 1 L | 2.113 pt | 1.760 pt | litre |

| dǒu | 市斗 | 10 | 10 L | 21.13 pt 2.64 gal |

17.60 pt 2.20 gal |

decalitre |

| dàn | 市石 | 100 | 100 L | 26.41 gal | 22.0 gal | hectolitre |

In the case of volume, the market and metric shēng coincide, being equal to one litre as shown in the table. The Chinese standard SI prefixes (for "milli-", "centi-", etc.) may be added to this word shēng.

Units of volume can also be obtained from any standard unit of length using the prefix 立方 lìfāng ("cubic"), as in 立方米 lìfāng mǐ for one cubic metre.

| Jyutping | Character | Relation to the Traditional Chinese Units (Macau) | Metric value |

|---|---|---|---|

| cyut3 | 撮 | 1⁄10甘特 | 1.031 L |

| gam1 dak6 | 甘特 | 1⁄10石 | 10.31 L |

| sek6 | 石 | None | 103.1 L |

These units are used to measure the mass of objects. They are also famous for measuring monetary objects such as gold and silver.

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄10000 | 3.7301 mg | 0.0001316 oz | |

| lí | 釐 | 1⁄1000 | 37.301 mg | 0.001316 oz | cash |

| fēn | 分 | 1⁄100 | 373.01 mg | 0.01316 oz | candareen |

| qián | 錢 | 1⁄10 | 3.7301 g | 0.1316 oz | mace or Chinese dram |

| liǎng | 兩 | 1 | 37.301 g | 1.316 oz | tael or Chinese ounce |

| jīn | 斤 | 16 | 596.816 g | 1.316 lb | catty or Chinese pound |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sī | 絲 | 1⁄1600000 | 312.5 μg | 0.00001102 oz | |

| háo | 毫 | 1⁄160000 | 3.125 mg | 0.0001102 oz | |

| lí | 市釐 | 1⁄16000 | 31.25 mg | 0.001102 oz | cash |

| fēn | 市分 | 1⁄1600 | 312.5 mg | 0.01102 oz | candareen |

| qián | 市錢 | 1⁄160 | 3.125 g | 0.1102 oz | mace or Chinese dram |

| liǎng | 市兩 | 1⁄16 | 31.25 g | 1.102 oz | tael or Chinese ounce |

| jīn | 市斤 | 1 | 500 g | 1.102 lb | catty or Chinese pound |

| dàn | 擔 | 100 | 50 kg | 110.2 lb | picul or Chinese hundredweight |

| Pinyin | Character[15] | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lí | 市厘 | 1⁄10000 | 50 mg | 0.001764 oz | cash |

| fēn | 市分 | 1⁄1000 | 500 mg | 0.01764 oz | candareen |

| qián | 市錢 | 1⁄100 | 5 g | 0.1764 oz | mace or Chinese dram |

| liǎng | 市兩 | 1⁄10 | 50 g | 1.764 oz | tael or Chinese ounce |

| jīn | 市斤 | 1 | 500 g | 1.102 lb | catty or Chinese pound formerly 16 liang = 1 jin |

| dàn | 市擔 | 100 | 50 kg | 110.2 lb | picul or Chinese hundredweight |

The Chinese word for gram is 克 kè; this can take the Chinese standard SI prefixes (for "milli-", "deca-", and so on). A kilogram, however, is commonly called 公斤 gōngjīn, i.e. a metric jīn.

| Jyutping | Character | English | Portuguese | Relative value | Relation to the Traditional Chinese Units (Macau) | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lei4 | 厘 | cash | liz | 1⁄16000 | 1⁄10 condorim | 37.79931 mg | 0.02133 dr | Not defined in Hong Kong. Macanese definition may not be correct when dividing catty. |

| fan1 | 分 | candareen (fan) | condorim | 1⁄1600 | 1⁄10 maz | 377.9936375 mg | 0.2133 dr | Macanese definition of 377.9931 mg may not be correct when dividing catty. |

| cin4 | 錢 | mace (tsin) | maz | 1⁄160 | 1⁄10 tael | 3.779936375 g | 2.1333 dr | Macanese definition of 3.779931 g may not be correct when dividing catty. |

| loeng2 | 兩 | tael (leung) | tael | 1⁄16 | 1⁄16 cate | 37.79936375 g | 1.3333 oz | Macanese definition of 37.79931 g may not be correct when dividing catty. |

| gan1 | 斤 | catty (jin, kan) | cate | 1 | 1⁄100 pico | 604.78982 g | 1.3333 lb | Hong Kong and Macau share the definition. |

| daam3 | 擔 | picul (tam) | pico | 100 | None | 60.478982 kg | 133.3333 lb | Hong Kong and Macau share the definition. |

| Ding | 1000 kg |

These are used for trading precious metals such as gold and silver.

| English | Character | Relative value | Metric value | Imperial value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| candareen troy | 金衡分 | 1⁄100 | 374.29 mg | 0.096 drt | |

| mace troy | 金衡錢 | 1⁄10 | 3.7429 g | 0.96 drt | |

| tael troy | 金衡兩 | 1 | 37.429 g | 1.2 ozt |

| Pinyin | Character | Relative value | Western value | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional value | Modern value | Traditional value | Modern value | |||

| miǎo | 秒 | 144 milliseconds | 1 second | |||

| fēn | 分 | 100 miǎo | 60 miǎo | 14.4 seconds | 1 minute | |

| kè | 刻 | 1 minor kè = 10 fēn | 15 fēn | 2 minutes 24 seconds | 15 minutes | kè was defined at 1⁄96, 1⁄108, or 1⁄120 day during the Liang dynasty, and established at 1⁄96 day after the Qing dynasty. |

| 1 major kè = 60 fēn | 14 minutes 24 seconds | |||||

| diǎn | 點 (T) 点 (S) |

100 fēn | 60 fēn | 24 minutes | 1 hour | |

| shí[16] | 時 (T) 时 (S) |

8+1⁄3 kè | 4 kè | 2 hours | 1 hour | the xiǎoshí(小時, lit. minor shí) is currently a unit used to express "hour" in order to avoid ambiguity |

| (pre-Qin) 10 kè | 2 hours 24 minutes | |||||

| shíchén | 時辰 (T) 时辰 (S) |

8+1⁄3 kè | - | 2 hours | - | |

| (pre-Qin) 10 kè | 2 hours 24 minutes | |||||

| xiǎoshí | 小時 (T) 小时 (S) |

- | 60 fēn | - | 1 hour | |

| rì / tiān | 日/天 | 12 shíchén | 24 xiǎoshí | 24 hours | 1 day | |

As there were hundreds of unofficial measures in use, the bibliography is quite vast. The editions of Wu Chenglou's 1937 History of Chinese Measurement[17] were the usual standard up to the 1980s or so, but rely mostly on surviving literary accounts. Newer research has put more emphasis on archeological discoveries.[18] Qiu Guangming & Zhang Yanming's 2005 bilingual Concise History of Ancient Chinese Measures and Weights summarizes these findings.[19] A relatively recent and comprehensive bibliography, organized by period studied, has been compiled in 2012 by Cao & al.;[20] for a shorter list, see Wilkinson's year 2000 Chinese History.[18]