Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| San Diego River | |

|---|---|

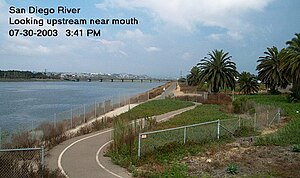

Looking upstream near mouth | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | San Diego County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Cuyamaca Mountains |

| • location | 5 miles (8 km) northwest of Julian, California |

| • coordinates | 33°07′09″N 116°39′00″W / 33.11917°N 116.65000°W[1] |

| • elevation | 3,750 ft (1,140 m) |

| Mouth | Mission Bay |

• location | Community of Ocean Beach, San Diego, California |

• coordinates | 32°45′37″N 117°12′45″W / 32.76028°N 117.21250°W[1] |

• elevation | 13 ft (4.0 m)[1] |

| Length | 52 mi (84 km) |

| Basin size | 420 sq mi (1,100 km2)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 38.3 cu ft/s (1.08 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 94,500 cu ft/s (2,680 m3/s) |

The San Diego River is a river in San Diego County, California. It originates in the Cuyamaca Mountains northwest of the town of Julian, then flows to the southwest until it reaches the El Capitan Reservoir, the second-largest reservoir in the river's watershed at 112,800 acre-feet (139,100,000 m3). Below El Capitan Dam, the river runs west through Santee and San Diego. While passing through Tierrasanta it goes through Mission Trails Regional Park, one of the largest urban parks in America.

It flows near Mission San Diego de Alcalá. The river's valley downstream from there is known as Mission Valley for that reason. The valley forms a transportation corridor for Interstate 8 and the San Diego Trolley's Green Line. The river discharges into the Pacific Ocean near the entrance to Mission Bay, forming an estuary.

The river has changed its course several times in recorded history. Prior to 1821, the San Diego River usually entered San Diego Bay. In the fall of 1821, however, a flood changed the river channel in one night, and the greater volume of the flow was diverted into what was then known as False Bay (now referred to as Mission Bay), leaving only a small stream still flowing into the harbor (J. C. Hayes 1874). This flood was remarkable in that no rain fell along the coast. The river was later observed to flow into San Diego Harbor in 1849 and 1856, and the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey map of 1859 shows it to be flowing there once again. Because of the high deposition rate of the river, which threatened to ruin San Diego Bay as a harbor, the federal government diverted the flow into Mission Bay and built a levee embankment, Derby Dike, of earth extending from near Old Town to Point Loma in the fall of 1853 (Derby 1853). Later that year, heavy rains caused the river to change course once again, washing out part of the levee and resuming its old course into the harbor (San Diego Herald 1855).

The worst flood in this area was in 1862. This was part of the Great Flood of 1862, which impacted the entire Western United States, and had a bearing on the Civil War. In San Diego, Mission Valley was inundated, and houses in lower Old Town were flooded when severe winds from a sea storm from the south backed the water up from the bay into the river (Pourade 1964:250). This flood was very significant because it held its peak for over twenty-four hours. In 1876, the levee was reconstructed, and no further diversions into San Diego Bay have occurred. Since then, a considerable volume of sediment has been added to the San Diego River delta in Mission Bay from occasional floods.

In 1935 El Capitan Dam was constructed 27 miles up the San Diego River; this reduced the sediment entering the bay considerably. An earlier dam was overtopped in 1916, increasing the floodwaters coming down Mission Valley at the time. The Mission Bay and San Diego River jetties were built in 1948, at a time when the shore of the bay was subject to alternating periods of recession and advance. By February 1951, the river levees had been connected to the jetties. All tidal flow was confined to a new channel. Since the river discharges only during flooding, the middle channel was soon completely filled. The channels were finished by 1955, after various difficulties were overcome and the jetties were considerably lengthened so that shallow bars would not form in the entrance.[3]

As San Diego’s Mission Vally grew in size, many businesses located along the banks of the San Diego River began to flood during heavy rain events. The flooding became so extreme that land owners on either side of the San Diego River got together to hatch a plan to contain the 100 year/1 hour rain events. Two men, Dean Wolf (of Mission Valley Center) and Denny Martini of the Bond Ranch (who owned ¾ of Mission Valley in 1908); conceived the idea of straightening out the San Diego River to prevent "back flow" along the natural curves where flooding took place. 10 years and over a million dollars was spent developing a plan to build a series of box culverts with rip rap, “hump back” river banks, islands, and hydro seeding. This plan would come to be known as the First San Diego River Improvement Project or FISDRIP. However, the project stalled in 1986 during the financial crisis of the same year. In a last-ditch effort to revive the project the Bond Ranch employed Robert Rodriguez (VP, Merrill Lynch Commercial Real Estate) to spearhead the issuance of Bonds to privately finance the project. The total cost to complete the project was 36 million dollars.

At this point in time the partnership was showing signs of falling apart. Robert Rodriguez and Denny Martini decided to bring all of the owners together in the same room to sign a historic agreement known as the CHSM agreement. Trammell Crow/Bruce Hazard, Conrock, Don Samis, and May Department Stores were all party to the agreement. The agreement when implemented formed the largest assessment district ever put in place by the City of San Diego, and the largest Specific Plan ever adopted by the City of San Diego at that time. In short; private funding would be acquired through the issuance of bonds that were collateralized by the land on either side of the river. The funds would be used to straighten out the San Diego River. Additionally, land would be donated to the City of San Diego for the construction of the Trolly to help alleviate traffic congestion. In return the City allowed the reclamation of land for development on formerly “floodway fringe zone”. Most development in Mission Valley today originated with the CHISM agreement.

In September of 1987 the City of San Diego awarded the project a Resolution of Intent and a Notice to Proceed with the First San Diego River Improvement Project.

In 1921, the city of San Diego filed suit against the Cuyamaca Water Company to establish its paramount right to the water of the San Diego River. After several court cases, the California State Supreme Court declared in 1929 that the city's right was paramount because under Spanish and Mexican laws, Pueblo San Diego was given exclusive rights to the use of the San Diego River, both surface and underground. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo obligated the U.S. to protect the grants and privileges decreed under the old rule.[4]

The river travels 52 miles (84 km) from its headwaters to the ocean. The river's tributaries include:

Four additional reservoirs lie in the river's watershed. Cuyamaca Reservoir is located on Boulder Creek and San Vicente Reservoir is fed by San Vicente Creek. Lake Jennings and Lake Murray are formed by the damming of canyons.

The San Diego River Park Foundation was founded in 2001 and is dedicated to conserving the water, wildlife, recreation, culture and community involved with the San Diego River.[5]

The San Diego River Conservancy was established by an act of the California Legislature to preserve, restore and enhance the San Diego River area. The Conservancy is a non-regulatory agency of the state government with an independent nine-member governing board. It is tasked to acquire, manage and conserve land and to protect or provide recreational opportunities, open space, wildlife species and habitat, wetlands, water quality, natural flood conveyance, historical/cultural resources, and educational opportunities. One important goal is to help create a river-long park and hiking trail, stretching the full length of the river from its headwaters in the Cuyamaca Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.[6]

From mouth to source:

San Diego

|

Santee

Lakeside

Julian

|