Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

SATNET, also known as the Atlantic Packet Satellite Network, was an early satellite network that formed an initial segment of the Internet. It was implemented by BBN Technologies under the direction of ARPA.

The first heterogeneous computer network was implemented in 1973, connecting the ARPANET to University College London. This evolved into SATNET. The first Transmission Control Program demonstration, linking SATNET, the ARPANET, and PRNET took place on November 22, 1977.

SATNET had its origins in Larry Roberts' 1970 proposal for a link between the ARPANET and the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) network. The NPL network was developed by Donald Davies, one of two independent inventors of the concept of packet switching. ARPA had an existing 2.4 kilobit/second link to NORSAR (used for seismic research), which at the time passed through a satellite station in the UK, then continued via cable to Norway.[1]

Peter T. Kirstein's research group at University College London (UCL) was chosen instead of NPL in 1971 to connect the ARPANET. Funding was finally approved in 1973, by which time the trans-Atlantic connectivity had changed: the NORSAR link now crossed the Atlantic via the Nordic satellite station in Tanum, Sweden, then continued via cable to Norway.[2] Two ARPANET Terminal Interface Processors (TIPs) were installed in Norway and connected to the ARPANET via satellite in June and September 1973. The UCL connection via a terrestrial circuit to Norway became operational in July 1973 at 9.6 kilobits/second. At this point, UCL was connected to the ARPANET, forming the first heterogeneous interconnected network in the world. UCL later provided a gateway for an interconnection with the SRCnet, the forerunner of the UK's JANET network.[1]

In that same year, Larry Roberts proposed that it would be possible to use a satellite's 64 kilobit/second link as a medium shared by multiple satellite earth stations within the beam's footprint.

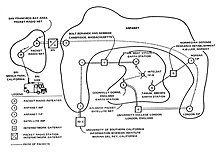

This proposal was implemented by Bob Kahn, and resulted in SATNET. Key participants in SATNET included BBN Technologies, COMSAT, the Linkabit Corporation,[3] UCLA, University College London, the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment and the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment in Britain. By the late 1970s, SATNET connected research sites in the US, UK, Norway, Germany, and Italy.[4]

In 1973, Bob Kahn considered the interconnection of the ARPANET with other networks. He enlisted Vint Cerf, who was teaching at Stanford. The problem was that the ARPANET, SATNET, and radio-based PRNET all had different interfaces, packet sizes, labelling, conventions and transmission rates. Linking them together was very difficult. In response, Kahn and Cerf set about designing a net-to-net connection protocol. Cerf led the newly formed International Network Working Group (INWG). In September 1973, the two gave their first paper on the new Transmission Control Program at an INWG meeting at the University of Sussex in England. Their proposal, published the next year, incorporated concepts developed by Louis Pouzin and Hubert Zimmermann, designers of the CYCLADES network.[5][6]

The first Transmission Control Program demonstration, linking SATNET, the ARPANET, and PRNET took place on November 22, 1977. As a result of this work, SATNET played a central role in the creation of the Internet protocol suite.

Peter Kirstein chaired the International Cooperation Board (ICB), formed by Cerf in 1979, to coordinate activities to develop packet satellite research.[7][8]

SATNET was assigned the 4.x.x.x/8 IPv4 address range in the List of assigned /8 IPv4 address blocks.

In later years, J. C. R. Licklider remembered the difficulty in arranging such satellite links during his second ARPA tour:[9]

When I was [at ARPA in 1974-1975], we were trying to set up a satellite link with Britain, and to deal with British General Post Office, or whatever that's called, was just a totally different experience to me from anything else. They wanted us to buy insurance covering their whole plant, practically, in case our IMPs set fire, or something, to their equipment. It was really weird. Their worst fear was that somebody in Europe would call up, through some kind of a network, to a British Telephone installation, and get through it into the Atlantic link and get to the United States, and somehow bypass the fifteen cent toll, and, "Christ," I said, "this is just a research and development thing. If we can make it work, if it really turns out to be a great idea, we can figure out about rates and stuff." We wanted to extend an Arpanet link -- we needed in a desperate way to extend the Arpanet link to Stuttgart, and to some American military base down there -- I forget the name of it -- and they would never let us have the one little link.

The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations.

In the early 1970s Mr Pouzin created an innovative data network that linked locations in France, Italy and Britain. Its simplicity and efficiency pointed the way to a network that could connect not just dozens of machines, but millions of them. It captured the imagination of Dr Cerf and Dr Kahn, who included aspects of its design in the protocols that now power the internet.