Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Argentina | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation | |||||

| National railway | Ferrocarriles Argentinos SE | ||||

| Infrastructure company | ADIFSE | ||||

| Major operators | Trenes Argentinos | ||||

| Statistics | |||||

| Ridership | 423,202,522 Buenos Aires commuter (2018)[1] 2,036,792 regional (2018)[2] 1,009,357 long distance (2018) | ||||

| System length | |||||

| Total | 17,866 km (11,101 mi) (8th)[3] | ||||

| Track gauge | |||||

| 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) | 26,475 km (16,451 mi) | ||||

| 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | 2,780 km (1,730 mi) | ||||

| 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) | 7,711 km (4,791 mi) | ||||

| Secondary narrow gauges | 424 km (263 mi) | ||||

| |||||

The Argentine railway network consisted of a 47,000 km (29,204 mi) network at the end of the Second World War and was, in its time, one of the most extensive and prosperous in the world. However, with the increase in highway construction, there followed a sharp decline in railway profitability, leading to the break-up in 1993 of Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), the state railroad corporation. During the period following privatisation, private and provincial railway companies were created and resurrected some of the major passenger routes that FA once operated.

Dissatisfied with the private management of the railways, beginning in 2012 and following the Once Tragedy, the national government started to re-nationalise some of the private operators and ceased to renew their contracts. At the same time, Operadora Ferroviaria Sociedad del Estado (SOFSE) was formed to manage the lines which were gradually taken over by the government in this period and Argentina's railways began receiving far greater investment than in previous decades.[4][5][6] In 2014, the government also began replacing the long distance rolling stock and rails and ultimately put forward a proposal in 2015 which revived Ferrocarriles Argentinos as Nuevos Ferrocarriles Argentinos later that year.[7][8][9][10]

The railroad network, with its 17,866 km (11,101 mi) (2018) size, is smaller than it once was, though still the 16th largest in the world,[3] and the 27th largest in passenger numbers.

The growth and decline of the Argentine railways are tied heavily with the history of the country as a whole, reflecting its economic and political situation at numerous points in history, reaching its high point when Argentina ranked among the 10 richest economies in the world (measured in GDP per capita) during the country's Belle Époque and subsequently deteriorating along with the hopes of the prosperity it came so close to achieving.[11]

In the early years, the railway was emblematic of the vast waves of European Immigration into the country, with many coming to work on and operate the railways, such as the Italian-Argentine Alfonso Covassi, the country's first engine driver,[12] and also in the sense that the population boom experienced as a result of this immigration required means of transportation to meet growing demands. Much like in the American West, the railways also played a key role in the creation and expansion of new population centres and boomtowns in remote parts of the country.[13]

The importance of foreign capital in the construction of the Argentine railways is perhaps overstated,[14] with initial construction of the network beginning in 1855 at first with Argentine finance, which continued throughout the network's development.[15] The Buenos Aires Western, Great Western and Great Southern railways (today the part of the San Martín, Sarmiento and Roca railways respectively) were all commenced using Argentine capital with the Buenos Aires Western Railway being the first to open its doors in the country, along with its Del Parque railway station.[16]

Following the adoption of liberal economic policies by president Bartolomé Mitre, these railways were sold off to foreign private interests, consisting of mostly British companies, in what would be the first of many acts where the ideological climate of the time would define the fate of the Argentine railways.[17] These sales also included Argentina's first railway, the Buenos Aires Western (by now 1,014 km (630 mi) long), which was sold in 1890 to the British company New Western Railway of Buenos Aires for just over 8.1 million pounds (close to £500 million in 2005 money[18]).[19] This sale, and others that came after it, was heavily criticised at the time for being far lower than the actual value of the railway, and prompted many anti-British protests.[14] In later years, this was also criticised by historians:

During the 27 years in which it belonged to the Government of the Province of Buenos Aires, the Western Railway was the line which was most luxurious, least wasteful [...] and offered the most economical fares and cargo rates. It was a model company which was the pride of Argentina, in relation to which all the English railway companies established in our country were, without exception, second-rate…[But after the sale] the unnecessary growth in spending, largely due to the disproportionate increase in employees, the resulting decrease in returns and the rise in ticket prices made up a definite intent to sabotage: the Western Railway would quickly be discredited in the public opinion.

— Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz, Historia de los Ferrocarriles Argentinos [20]

In the years that followed, there were numerous cases of undervalued sales to British investors, including the 1,000 km (621 mi) long Andean Railway, which provoked much anti-British sentiment in the country.[21] By 1910 the network had been monopolised by British companies, owned by large finance firms such as J.S. Morgan & Co. in London.[21] Nevertheless, major development of the Argentine rail network occurred up to this period and the Argentine state also played a large role, financing ferrocarriles de fomento (development railways) in rural areas not attractive to private interests,[12] while the Argentine State Railway had a 9,690 km (6,020 mi) network.[22]

By 1914, the Argentine rail network attained significant growth having added 30,000 km (19,000 mi) to the network between 1895 and 1914,[23] which positioned the country as having the tenth largest rail network in the world in that year, at a point where the country had the tenth highest per-capita GDP in the world.[24] Its expansion accelerated greatly due to the need for the transport of agricultural products and cattle in Buenos Aires Province. The rail network converged on the city of Buenos Aires and was a key component in the development of the Argentine economy as it rose to be a leading export country. However, with the advent of the First World War, then subsequently the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression, the rail network of the country experienced a much lower rate of growth after this period and had mostly ground to a halt by the beginning of the Second World War.[25][26]

| Railroad network growth and expansion[27] | |||||||

| Years | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System length (kilometres) | 9.8 | 722 | 2,516 | 9,397 | 16,500 | 29,094 | 47,000 |

| Passengers transported (millions) | – | – | 3 | – | 18 | – | 145 |

| Cargo transported (x 1,000,000 tonnes) | – | – | 1.0 | – | 11.8 | – | 45.5 |

By the end of the Second World War, the United Kingdom owed Argentina m$n 2 billion after the country had filled the gaps in food shortages during the war effort.[28][29] Following what was then a worldwide trend, the private companies were nationalised by the government of Juan Perón, beginning in 1946 with the French railways and then purchasing the British railways after an agreement was signed cancelling the British debt in 1947.[30][31] Perón later claimed in an interview that the British envoys had offered him a bribe of US$100 million if the state paid an extra m$n 6 billion for the railways on top of the debt cancellation.[28]

After the 1948 nationalisation, the 47,000 km (29,000 mi) long Argentine railway network was separated into six divisions managed by State-owned company Ferrocarriles Argentinos. Of the 20 railways incorporated into Ferrocarriles Argentinos, 7 were Argentine, 10 were British and 3 were French prior to nationalisation. There were grouped together by track gauge and location and named after important figures in Argentine History. Maps of those division companies were as follows:

Soon after the reorganisation, Perón turned it into a political matter with the nationalisation becoming a symbol of national autonomy and independence from foreign powers rather than an administrative change and is still to this day regarded by justicialists as a move against neo-imperialsm.[32][33] Although for many years the state-owned railways were able to provide a good standard of passenger and freight service, over the years the changing politics of Argentina began to take its toll. By the 1960s, the post-war economic boom had ushered in a new age of the automobile, with rail transport on its way out around the world, a trend from which Argentina was not left unscathed.[23]

Following the ousting of Perón from power, the Larkin Plan was implemented to modernise transport in the country with backing from the World Bank and intended to make investments in the country's railways.[34] However, by 1961 its aims had changed significantly and the plan had evolved into one which prioritised automobile transportation and began lifting sections of railway - an act which was put to an end following a series of strikes by railway workers in opposition to the plan.[35] The government favoured road transport and opened car and truck factories in the country. Diesel train shops and new car shops were opened with help from Fiat, Alstom, and Mitsubishi. Steam locomotives were slowly phased out. Later governments between 1967 and 1971 then continued investing in the railways and enacted modernisation plans, renewing much of the rolling stock and the railways continued to function well.[36]

Under the military junta, the 1970s and 1980s saw a significant decline in Argentina's railways. In 1965, 25% of cargo and 18% of passengers were transported by rail, while by 1980 this figure had dropped to 8% and 7% respectively and Ferrocarriles Argentinos was losing US$1 million per day maintaining an ageing system with dwindling passenger numbers.[37] Between 1976 and 1980, 560 stations were closed, along with 5,500 km (3,400 mi) of track, while the number of employees in railway workshops alone fell from 155,000 to 97,000.[38]

By the time the country returned to democratic rule, the railways were in bad shape and the country was overwhelmed by the economic burdens and debts left over from the junta.[39] Under this context, and with the state unable to cope with the cost of managing the railways due to a large fiscal deficit, the privatisation of the network came into consideration.

Under the presidency of Carlos Menem, Argentina radically changed its economic policies moving from a more Import substitution industrialisation-orientated model towards neoliberal shock therapy and the Washington Consensus under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund.[40][41] Much like under the classical liberalism of the late 19th and early 20th century, under these plans, Argentina would sell off most of its state assets at extremely reduced prices, among them the railways.[36][42]

During these reforms, between 1992 and 1995, the government decided break up and to privatise the state-owned company Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), which comprised six relatively independent divisions, Sarmiento, Mitre, Urquiza, San Martín, Belgrano and Roca, and granted concessions to private companies for their operation through competitive bidding, while doing the same with freight services.[43]

At the start of the concessions, the railway network was quickly reduced to one quarter of its capacity, with long distance lines disappearing almost completely.[23][44] At the same time, as more locomotives and rolling stock were needed, the private companies became increasingly reluctant to make the investment required to increase capacity and thus service quality and passenger numbers declined.[23] Railway privatisation resulted in the loss of some 70,000 jobs in the railway sector over the years, whilst by 1998 some 793 railway stations had been closed.[45] In addition, companies operating other transport means (such as bus transport) who had vested interests seeking the demise of the railway, purchased lines for far less than their real value.[46]

Under privatisation, substantial government subsidies continued in order to keep the system from collapsing, the state continued losing money on the railways.[44] During this period, the railways were plagued by negligence, while private operators persistently ignored warnings from inspectors whilst failing in their contractual obligations to maintain railway infrastructure.[44] Similarly, over the years, government subsidies to the private companies increased to levels similar to the losses incurred under the state management of the railways, albeit now with a much more limited service and further deteriorated infrastructure.[46]

The closing of much of the rail system also led to the emptying of many rural towns dependent on the railways, creating ghost towns and therefore to a dismantling of the development that had taken place there since the arrival of trains.[47] Argentine agriculture found itself in the difficult position of shipping its goods less efficiently using road transport, which costs around 72% more than state-owned rail services.[48]

The economic crisis in 2001 was the final blow and neither the private companies nor the government could provide the service required. In 2003, the new administration of President Néstor Kirchner set it as a key policy objective to revive the national rail network. Although the economic upturn saw traffic grow again, the suburban rail operators were still little more than managers of government contracts rather than true entrepreneurs.[49]

In 2008, the National Government formed Trenes Argentinos Operadora Ferroviaria (SOFSE) to manage some freight and passenger lines in the country.[4] The Once Tragedy of February 2012 prompted further action by the government, resulting in the revocation of the Sarmiento Line and Mitre Line concessions from Trenes de Buenos Aires (TBA) in May of that year, with both lines eventually being put under the management of the state-owned SOFSE.[50][51] In June 2012, the government announced that it was renationalising some freight railways citing "serious breaches of contract" by the operators, this culminated in the nationalisation of the Belgrano Cargas network which operates on over 10,000 km (6,200 mi) of metre gauge track.[52][53]

This trend continued in the following years and the government began re-opening services and improving on the once private services using completely new rolling stock, including long distance services like the one from Buenos Aires to Mar del Plata and Buenos Aires-Rosario-Cordoba.[54][55] This new-found investment in the railways has not been limited to rolling stock since, in many cases, the state has completely replaced, or is in the process of replacing, the existing infrastructure with continuous welded rails on concrete sleepers and undertaking other works such as renovating level crossings and building new railway bridges.[56][57][58] The freight network has also received significant investment from China, with two investments totalling US$4.8 billion made in 2013 and 2015.[59]

While from 2008 to 2014 there were many indications that the state was re-nationalising parts of the railway and making efforts towards improving it, in 2015 it was announced that complete nationalisation of the remaining lines and services were on the table after a project was put forward that would see the resurrection of Ferrocarriles Argentinos as a state-owned holding company which would incorporate SOFSE (passenger services), TACyL (freight) and ADIFSE (infrastructure).[7] This was put into effect in April 2015 when, by overwhelming majority, the Argentine Senate passed the law which re-created Ferrocarriles Argentinos and effectively re-nationalised the country's railways, a move which saw support from all major political parties across the political spectrum.[8][9][10] Expenditure for the railway network was set at AR$ 9 billion for 2015, while in 2016 it is expected to be AR$7.2 billion.[60]

Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Cordoba, Resistencia, Paraná, La Plata, Santiago del Estero and Salta are the only cities in Argentina to offer suburban passenger services; most other cities rely on bus and trolleybus transportation, though in the past there were more networks and most major cities had a tramway network.

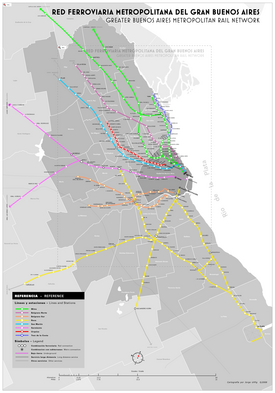

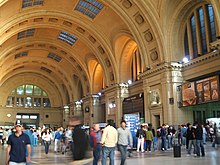

Greater Buenos Aires' metropolitan rail system is the second most extensive in the Americas after New York's commuter rail system, with about 259 stations, covering 900 km (559 mi) and 7 rail lines serving more than 1.4 million commuters daily in the Greater Buenos Aires area.[61][62] Commuter rail services from the suburbs is mostly operated by SOFSE, though some private operators remain. The rail lines converge at five rail terminals, all of them in Buenos Aires, with two, Retiro and Constitución rail terminals being the busiest train stations in Argentina, though there is a plan to connect all the lines in one central underground station for easy transfer.[61]

| Metropolitan railway transport | ||||

| Line | Operator | Length (Km) | N° stations | Annual ridership (2014)[62] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitre | Trenes Argentinos | 185,5 | 55 | 18,330,512 |

| Belgrano Norte | Ferrovías | 54,3 | 22 | 28,876,619 |

| Belgrano Sur | Trenes Argentinos | 66,3 | 30 | 10,974,454 |

| Roca | Trenes Argentinos | 237,2 | 70 | 115,032,946 |

| San Martín | Trenes Argentinos | 56,3 | 19 | 39,239,510 |

| Sarmiento | Trenes Argentinos | 184,1 | 40 | 39,663,847 |

| Urquiza | Metrovías | 29,9 | 23 | 12,585,106 |

| Totals: | 813 | 259 | 264,702,994 | |

Buenos Aires City's commuter rail provides 1800 trains carrying 1.4 million passengers each business day in the city of Buenos Aires, its suburbs in Greater Buenos Aires and several far-reaching satellite towns.[61] Service is provided by private companies and spreads out from five central stations in Buenos Aires: Retiro, Constitución, Once and Federico Lacroze – all serving both long-distance and local passenger services – and Buenos Aires Station which, despite its name, is a secondary rail terminus serving only local commuter services and will cease to be a terminal once the Belgrano Sur Line is extended to Constitución.[63]

The Retiro and Constitución train stations are linked by Line C of the Buenos Aires Underground, Once is served by Line A of the underground via its "Plaza Miserere" station and by Line H's Once station, while Federico Lacroze is served by Line B.[64] The smaller Buenos Aires Station is accessible by some city bus services and it is the only railway terminus in Buenos Aires that has no access to the Buenos Aires Underground, though it is connected to the Metrobus Sur line.[65]

Most trains leave at regular 8-20 minute intervals, though for trains travelling a longer distance service may be less frequent.[66] Fares are cheap and tickets can be purchased at ticket windows or through the SUBE card machines at stations.[67] Most of the lines are electrified, several are diesel-powered, while some of these are currently being electrified and some of the lines share traffic with freight services.

Buenos Aires area commuter rail lines were privatised in the 1990s, and passengers had complained for years about poor commuter rail services on lines leading from Constitución station in downtown Buenos Aires to the capital's southern suburbs.[68] However, in recent years all but two of the services have been re-nationalised and are operated by Trenes Argentinos (SOFSE).[69]

Buenos Aires once had one of the most extensive tramway systems in the world, with a 875 km (544 mi) network in the city proper alone, which gained the city global notoriety as being "The City of Trams" in the late 19th and early 20th century.[70][71] The system remained popular throughout its existence but, despite this, it was dismantled in the mid-1960s in favour of bus transport.[72] Today, some minor tram services remain, as well as light rail services in the city proper and Greater Buenos Aires.

The light rail Tren de la Costa (Train of the Coast), which serves tourists and local commuters, runs from the northern suburbs of Buenos Aires to Tigre along the river for approximately 15 km (9 mi). The line connects directly to the Mitre Line at Maipú–Bartolomé Mitre station in the northern suburb of Olivos for direct access to Retiro terminus in the centre of the city.[73]

An experimental project of a short run tramway line, Tranvía del Este, was inaugurated in 2007 in the Puerto Madero district of Buenos Aires. The 2 km (1.2 mi) prototype line ran between the Córdoba and Independencia avenues, ridership was not as expected and the line closed in 2012.[74] A Historic Tramway operates on weekends and holidays in the Caballito neighbourhood of the capital with free fares and using vintage rolling stock from the now defunct Buenos Aires tramway network.[75][76]

Another tramway line, the Buenos Aires Premetro, operates as a feeder at the end of Underground Line E, running through some of the city's southern districts.[77] Though there is currently only one Premetro line (E2), originally many other lines were planned to run as feeder services to the Buenos Aires Underground, however due to their planned construction coinciding with the privatisation of the Underground network, these never materialised.[78] The creation of new lines has been proposed as late as 2012, however it is now accepted that, with the creation of the Metrobus network in 2011, the need for further Premetro lines has been made redundant.[79][80]

The Buenos Aires public transit system uses a ticketing system. All tickets are bought at ticket booths and ticket printing consoles at railway stations and on board certain trains. Tickets can be bought either using cash or by using the SUBE card (also used throughout the country for buses, tollbooths and underground).[67] Ticket cost differ depending on the payment method: If the tickets are bought using SUBE, the user can benefit from a government subsidy which translates to a substantially reduced fare.[81] Children under three years of age, children in school uniform, retired people receiving pensions and the disabled do not have to pay to use these services in most cases.[82] Similarly, university students and staff have a 20% discount, with a 50% discount proposed in 2015.[83][needs update]

Although the first electric railway between Retiro and Tigre was inaugurated in 1916, major electrification projects were not adopted. The large size of the country, its long distances and flat topography mean that major electrification does not make much sense economically, although some suburban networks in Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area were electrified. After several decades of the Buenos Aires rail-service being under-funded, there is presently an ongoing modernisation plan so as to provide much needed improvement in services, and the trend is towards electrification of several lines. Similarly, ongoing maintenance and investment has continued on existing electric lines, such as with the $845 million purchase of 705 CSR electric multiple unit cars from China for the Mitre, Sarmiento and Roca lines in 2013.[84]

The first line to receive this improvement was the Roca Line network in the southern part of the city, where work is already in progress, and several new segments electrified in 2012, such as the Glew - Alejandro Korn route and the Temperley - Remedios de Escalada route.[85][86] The electrification of this line from Constitución railway station in Buenos Aires to the city of La Plata was completed in 2017.[87] In 2018, all routes were electrified except Bosques – Villa Elisa route, which only a portion is in service with diesel trains.[88]

It is expected that the San Martín Line will finish the electrification of its diesel segments in 2022.,[89] and there are plans to electrify the Belgrano Sur Line and remaining parts of the Sarmiento Line.[90][91][92] Both the Mitre and Sarmiento lines received completely new CSR electric multiple units in 2014. The Roca line's 300 coaches of the same type are in service, as the electrification of its remaining diesel segments was completed in 2018 (except Bosques – Villa Elisa route).[88]

In 2008, approximately 42.7%, 258 km (160 mi) from a total rail network of 604 km (375 mi) of the Buenos Aires and Greater Buenos Aires area (excluding outer-suburban satellite cities of Capilla del Señor, Lobos, Mercedes, Luján, Zárate and Cañuelas), but including the city of La Plata, was electrified. This is expected to increase by the end of 2015, when major electrification works are completed.[needs update]

La Plata is mostly served by the Roca Line, including the University train of La Plata, which runs from the central station to the National University of La Plata.[93] The segment of the Roca Line which runs from Buenos Aires Constitución to La Plata and its suburbs is electrified with new rolling stock, stations and track, with works having commenced in 2014 and completed in 2017.[94]

This line also provides commuter services to La Plata's city centre from neighborhoods like Tolosa, Ringuelet, City Bell and Villa Elisa, with a frequency of one train every 25 minutes, which is expected to drop to 12 minutes after the electrification is completed.[95] Up until the 1980s, there were also other commuter services on the General Roca Railway to nearby towns and suburbs, however they are no longer in use and there are no indications that they will be reactivated.[96]

The Metrotranvía Mendoza (Spanish for Mendoza Light Rail or fast tramway) is a public light rail transport system for the city of Mendoza, Argentina, served by articulated light rail cars operating on newly relaid tracks in former-Ferrocarril General San Martín mainline right-of-way. The tram system is unusual in the sense that, unlike the rest of railway services in Argentina,[97] the rail cars on this line run on the righthand track instead of the left.

The tram serves the metropolitan area of Mendoza, which includes the departments of Las Heras, Central district, Godoy Cruz, Maipú and Luján de Cuyo. As of 2013, only one line runs a 12.5 km (8 mi) stretch between Mendoza Central Station and General Gutierrez in Maipú, on double-track 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge track.[98] The finished project includes four lines, 46.5 km (29 mi) in length and 50 stations, also connecting downtown with the Airport.[99][100]

Construction of the first line (Línea Verde, or Green Line)[101] began in March 2009.[102] The system opened for regular service on 8 October 2012.[101] In February 2014, the local Government announced the start of constructing works for the second line, linking the city centre with the North, up to Panquehua, in Las Heras Department.[103]

The Tren del Valle (Train of the Valley) is a service that runs between the cities of Neuquén and Cipolletti in Neuquén and Río Negro provinces, expected to begin operating in July 2015 with 22 services per day.[104] While in the first phase of the reactivation of this line (closed in the 1990s after the privatisation of the network) takes it between these two cities, after the opening, it will continue to be extended to General Roca, Plottier and Añelo in 2015 and 2016.[105][106] The line uses Argentine-built Materfer CMM 400-2 DMUs and General Roca Railway tracks, which have been replaced along with the restoration of existing railway bridges, while parts of its route will be shared with YPF freight services that serve the vast Vaca Muerta oil fields in the provinces.[104][107][108] This line was once operated by the Buenos Aires Great Southern Railway, before railway nationalisation in 1948.

The Paraná urban railway is served by two local lines which run on the standard gauge General Urquiza Railway and link Paraná city -Capital of Entre Ríos province- with Colonia Avellaneda and Villa Fontana. The two lines are 9 and 13.4 km (8.3 mi) long, but there are further plans to expand the system. Villa Fontana's line was inaugurated in August 2010 up to Oro Verde and expanded to Villa Fontana in 2011. Colonia Avellaneda's line was inaugurated in March 2011.[109][110]

Paraná city is also linked with interurban services to Concepción del Uruguay and Concordia, Entre Rios' main cities.[111]

It serves Great Resistencia, the capital city of the province of Chaco with a 10 km (6.2 mi) line to Puerto Vilelas with 8 stations, and a 20 km (12 mi) line to Puerto Tirol with 16 stations. From the intermediate station of Cacuí in the Puerto Tirol Line leaves the interstate line to Los Amores in the province of Santa Fe. The whole network uses the former General Belgrano Railway 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge tracks.[112]

The system was originally operated by Chaco Railway Services, owned by the Province's Government, but in May 2010 operation was transferred to SOFSE, the state-owned railway company managed by the National Government.[113]

The Santa Fe Urban Train is project initiated in 2014 for a 3.7 km (2.3 mi) line which runs through the city of Santa Fe in Santa Fe Province using metre gauge General Belgrano Railway tracks.[114] In June 2015, the service underwent successful testing on the line and its 8 brand new stops, using Argentine-built TecnoTren railbuses.[115] Once fully opened in 2015, this will be the first commuter rail service in the city since railway privatisation in the 1990s, while it is estimated that using the train will be 40% faster than existing bus transport.[116][117]

The historical city of Santiago del Estero will have a commuter rail service called Tren al Desarrollo, which will run on a series of newly built viaducts over the city, as well as existing General Mitre Railway broad gauge tracks.[118] The 8 km (5.0 mi) line has undergone testing using Argentine TecnoTren rolling stock and will open to the public in 2016, though its central terminus was inaugurated in 2015.[119][120][121] After its aperture, the line will be further extended to the outskirts of the city, though it has also been considered to extend the line to the nearby city of San Miguel de Tucumán.[122][123]

Up until the mid-twentieth century, most major cities in Argentina had a tramway network, though today only a small number remain.[125][126] La Plata was the first Argentine city to receive an electric tramway network in 1892, rather than Buenos Aires which would see its existing network electrified from 1897 onwards.[72] By the mid-1960s, most cities had their tram networks dismantled and replaced with colectivos and trolleybuses. La Plata was the last city to operate trams in Argentina, with its last service operating in December 1966, until the 1980s when the Buenos Aires PreMetro began operations.[75][126]

The Buenos Aires Underground (Subterráneo de Buenos Aires-locally known as Subte) is a metro system that serves the city of Buenos Aires, the network was inaugurated in 1913 by the Anglo-Argentine Tramways Company, being the first of its kind in Latin America and in the entire Southern Hemisphere and Spanish speaking world.[127]

It currently has six lines, with a seventh underway a further two planned, carrying 365 million passengers per year on a 52 km (32 mi) network with 83 stations.[128][129] The network expanded quickly in its early years, but the rate of expansion had slowed by the 1960s, with serious attempts at expansion and modernisation only occurring in recent years.[130]

In the city of Córdoba, Argentina, there is a project to build an underground system; the Córdoba Metro, which would make it the second metro system in Argentina.[131] The network will be 33 kilometres long with 26 stations on 3 lines, with a total cost of $1.8 billion.[132] The city of Rosario has also proposed having its own metro system, which is currently being evaluated.[133]

Work has also begun in Buenos Aires to move the Sarmiento Line underground in an effort to decrease journey times whilst improving traffic conditions above ground. The project will be undertaken in three stages and, when completed, would mean that 32.6 kilometres of the line between Caballito and Moreno will be completely underground, with station entrances above ground similar to a metro system.[134] The existing above-ground line has continued to operate while work has occurred below ground for the corresponding sections.[135][136]

There is also a project announced in 2015 to create a 16 km (9.9 mi) series of tunnels to connect Retiro railway station, Once railway station and Constitución railway station.[137] The result of this would be the Red de Expresos Regionales, which would link together all of Buenos Aires' existing 812 km (505 mi) commuter rail network, allowing for passengers to travel from one side of Greater Buenos Aires to the other making only one connection at a central underground station underneath the Obelisco. The project will cost $1.8 billion and will be carried out in three stages, taking 8 years for it to be fully completed, though some parts are due to commence operation sooner.[61]

Argentina scrapped many of its uneconomical long-distance passenger train services during the early 1990s and privatised, by concession contract, several main routes to Trenes de Buenos Aires (TBA), Ferrocentral, Ferrobaires, and Trenes Especiales Argentinos. The new services were not what passengers were used to and, with the exception of the Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba and Tucumán corridors, provided erratic and poor-quality services. In recent years however, government policy has changed to one in which the state intends to re-open and operate all services which were formally closed.[138]

Under privatisation, many services ceased to operate for a variety of reasons. Among these were previously iconic routes such as Buenos Aires - Posadas and Buenos Aires - Bariloche.[139][140] Recently however, the national government has been replacing very large segments of track in important corridors and routes, using continuous welded rails on concrete sleepers to accommodate trains running at speeds of 160 km/h (99 mph).[141][142] Many of these improvements are nearing completion while others are under way and some are in the planning stages. Long-distance rail travel in Argentina has been described as considerably cheaper than air or bus travel, but also much slower, with maximum speeds of 50 km/h (31 mph) even on the newer stretches opened in 2017.[143]

In 2014 there was a 600% increase in spending on railway infrastructure, being spent on projects around the country to revive long distance services, while this expenditure is expected to be even higher in 2015.[144][145] To accommodate this revival in long distance services, Retiro railway station will receive a new expansion for the services being operated by SOFSE.[146] Similar projects are nearing completion in cities like Rosario, where a completely new railway terminal has been built in addition to the existing ones.[147]

At the same time, the high speed rail project which had been planned for the Buenos Aires - Rosario - Córdoba corridor has been put on hold since for the moment the routes are being refurbished for the 160 km/h (99 mph) services which are considered to be a higher priority, though as of 2015, Chinese proposals for high speed rail are still being considered.[148][149]

Inter-city services are currently served by two state-owned railway companies, Trenes Argentinos (that manages all the long-distance passenger rail services) and Ferrobaires (operating services in Buenos Aires Province). Ferrobaires has been criticised for the quality of its service,[150] though there have been signs that the company (owned by the province of Buenos Aires, rather than the national government) may be dissolved when its remaining services are taken over by Trenes Argentinos.[151]

Nowadays, some of the most important cities of Argentina are served by train, departing from Constitucion, Once and Retiro terminus located in the centre of Buenos Aires. Some cities currently are: Mar del Plata, Rosario (both stations, Norte and Sur, Córdoba, General Pico, Santa Rosa, Rufino and San Miguel de Tucumán.[152]

Other regional services are operated by their respectives Provinces, such as Tren a las Nubes (operated by the Government of Salta) and Servicios Ferroviarios Patagónico (also known as "Tren Patagónico") by the Río Negro Province.

Buenos Aires

Córdoba

Entre Ríos

Mendoza

Misiones

Patagonia

Rosario

Salta

Tierra del Fuego

There are several private freight operators in Argentina, along with the state-owned Trenes Argentinos Cargas y Logística. In 2012, the network carried 12,111 million tonne-kilometres (tonnes x distance travelled).[172] The amount of freight carried by individual operators in 2014 was as follows:

| Freight carried in Argentina (2014) | ||

| Operator | Freight carried (tonnes) [173] | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Nuevo Central Argentino | 7,408,914 | Private |

| Ferrosur Roca | 5,258,301 | Private |

| Ferroexpreso Pampeano | 3,500,009 | Private |

| TACyL | 3,155,301 | State-owned |

| Total: | 19,317,525 | - |

Trenes Argentinos Cargas y Logistica (TACyL) is a state-owned company created out of the Belgrano Cargas network after the national government terminated the company's contract in 2013, returning it to state control while citing the lack of competitiveness in the private sector as a primary reason for the move.[174][175] Later that year, the government revoked concessions from Brazilian company América Latina Logística citing "serious" contract violations and imposing heavy fines on the company for being in breach of contract.[176] The services managed by this company were also integrated into the new TACyL holding company.[177]

Following the creation of TACyL, the national government began investing heavily in the country's freight network with an AR$12 billion investment to improve its infrastructure, renewing 30% of the rails over the following 2 years.[178] This investment also included purchasing 100 locomotives and 3,500 freight cars from China for TACyL which are expected to arrive in 2015, while a separate investment saw the purchase of a further 1,000 cars from Argentine company Fabricaciones Militares.[178][179] Further renovation of infrastructure for passenger lines, such as the complete replacement of rails on the Buenos Aires - Rosario - Córdoba - Tucumán route of the General Mitre Railway, will aid private operators such as Nuevo Central Argentino who use those segments.[180][181]

Soon after nationalisation, the government began looking to expand the fleet of the company and began making orders both domestically and abroad. One order consisted of 1000 freight wagons from Argentine state-owned company Fabricaciones Militares.[179] The company also ordered 100 locomotives and 3,500 carriages from China as part of a plan that also included the purchase of 30,000 rails to repair parts of the line.[182] In September 2015, it was announced that the original Chinese investment of US$2.4 billion in the Argentine freight network was being doubled to US$4.8 billion and new purchases and infrastructure projects would ensue.[183]

Prior to the deterioration of the rail network, Argentina had a greater number of rolling stock manufacturers which supplied trains and cars throughout the railways, however today only a few companies like Materfer, Grupo Emepa, TecnoTren and Fabricaciones Militares remain. While Materfer make the CMM 400-2 diesel multiple units and the MTF-3300 diesel cargo locomotives, Emepa manufacture the Alerce EMU/DMU which is to be used on the Belgrano Norte Line.[184][185] At the same time, Fabricaciones Militares only makes freight cars, such as those used in the Belgrano Cargas network, though in the past they made electric trains for suburban and underground lines.[179] There have been signs that the industry is reviving and expanding, while at the same time there are many workshops around the country which refurbish and modernise older rolling stock.[186][187]

Though the industry is being revived, the country no longer has the capacity to manufacture long-distance locomotives and EMUs for suburban lines, so these are mostly imported from China and are made by companies such as CSR Corporation Limited and China CNR Corporation, with CSR planning to open a factory in Argentina and purchasing the Argentine company Emprendimientos Ferroviarios, which is now its subsidiary.[188][189]

The worst rail accident in Argentina in terms of fatalities occurred on 1 February 1970 when two trains collided near Ingeniero Maschwitz in Greater Buenos Aires.[194][195] This due to a passenger train carrying 700 people coming to a halt with mechanical problems, while a long distance General Mitre Railway train carrying 500 passengers from Tucumán crashed into it from behind.[196] The total death toll was 142 people, with 368 injured.[196][197]

From 2008 to 2012, there were a series of rail accidents which eventually led to the re-nationalisation of the rail network. Before dawn on 9 March 2008, a passenger train slammed into a bus at a rural Argentine level crossing, near Dolores, some 125 miles (201 km) south of Buenos Aires, killing 18 people and leaving at least 47 others injured. The bus driver ignored the warning lights and lowered crossing gates.[198]

On 13 September 2011, a passenger train operated by Trenes de Buenos Aires hit a bus on a level crossing at Flores in Buenos Aires during the morning rush hour, killing 11 people and injuring 265.[199] The train derailed, and crashed into a train standing at the platform in the adjacent station. The bus driver had ignored warning lights and a partly lowered barrier.[200]

The second-worst rail accident in terms of fatalities occurred on 22 February 2012 a passenger train operated by TBA crashed into the solid buffers at the Once station near downtown Buenos Aires, killing 51 people and injuring over 700 others.[201][202] President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner called for two days of national mourning following the accident.[203]

Following these accidents, all of TBA's concessions were revoked and the national government began restoring rail infrastructure and purchasing brand new rolling stock for Buenos Aires' commuter rail lines, as well as huge investment across the country.[6][144][204] These moves eventually led to the complete re-nationalisation of the country's railway network, with safety concerns under private operation being one of the primary reasons.[205][206]