Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

Mucilage is a thick gluey substance produced by nearly all plants and some microorganisms. These microorganisms include protists which use it for their locomotion, with the direction of their movement always opposite to that of the secretion of mucilage.[1] It is a polar glycoprotein and an exopolysaccharide. Mucilage in plants plays a role in the storage of water and food, seed germination, and thickening membranes. Cacti (and other succulents) and flax seeds are especially rich sources of mucilage.[2]

Exopolysaccharides are the most stabilising factor for microaggregates and are widely distributed in soils. Therefore, exopolysaccharide-producing "soil algae" play a vital role in the ecology of the world's soils. The substance covers the outside of, for example, unicellular or filamentous green algae and cyanobacteria. Amongst the green algae especially, the group Volvocales are known to produce exopolysaccharides at a certain point in their life cycle. It occurs in almost all plants, but usually in small amounts. It is frequently associated with substances like tannins and alkaloids.[3]

Mucilage has a unique purpose in some carnivorous plants. The plant genera Drosera (sundews), Pinguicula (butterworts), and others have leaves studded with mucilage-secreting glands, and use a "flypaper trap" to capture insects.[4]

Mucilage is edible. It is used in medicine as it relieves irritation of mucous membranes by forming a protective film. It is known to act as a soluble, or viscous, dietary fiber that thickens the fecal mass, an example being the consumption of fiber supplements containing psyllium seed husks.[5]

Traditionally, marshmallows were made from the extract of the mucilaginous root of the marshmallow plant (Althaea officinalis). The inner bark of the slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), a North American tree species, has long been used as a demulcent and cough medicine, and is still produced commercially for that purpose.[6]

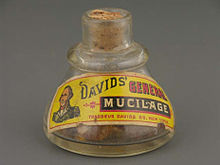

Mucilage mixed with water has been used as a glue, especially for bonding paper items such as labels, postage stamps, and envelope flaps.[7] Differing types and varying strengths of mucilage can also be used for other adhesive applications, including gluing labels to metal cans, wood to china, and leather to pasteboard.[8] During the fermentation of nattō soybeans, extracellular enzymes produced by the bacterium Bacillus natto react with soybean sugars to produce mucilage. The amount and viscosity of the mucilage are important nattō characteristics, contributing to nattō's unique taste and smell.

The mucilage of two kinds of insectivorous plants, sundew (Drosera)[9] and butterwort (Pinguicula),[10] is used for the traditional production of a variant of the yogurt-like Swedish dairy product called filmjölk.[11][12]

The presence of mucilage in seeds affects important ecological processes in some plant species, such as tolerance of water stress, competition via allelopathy, or facilitation of germination through attachment to soil particles.[13][14][15] Some authors have also suggested a role of seed mucilage in protecting DNA material from irradiation damage.[16] The amount of mucilage produced per seed has been shown to vary across the distribution range of a species, in relation with local environmental conditions of the populations.[17]

A variety of maize grows aerial roots that produce a sweet mucus. The Sierra Mixe is a tall variety that survives in poor soils without fertilizer in Oaxaca, Mexico, and the mucilage has been shown to support nitrogen fixation through bacteria that thrive in its high-sugar, low-oxygen environment.[18]

The following plant and algae species are known to contain far greater concentrations of mucilage than typical: