Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

The military history of Greece during World War II began on 28 October 1940, when the Italian Army invaded Greece from Albania, beginning the Greco-Italian War. The Greek Army temporarily halted the invasion and pushed the Italians back into Albania. The Greek successes forced Nazi Germany to intervene. The Germans invaded Greece and Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, and overran both countries within a month, despite British aid to Greece in the form of an expeditionary corps. The conquest of Greece was completed in May with the capture of Crete from the air, although the Fallschirmjäger (German paratroopers) suffered such extensive casualties in this operation that the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (German High Command) abandoned large-scale airborne operations for the remainder of the war. The German diversion of resources in the Balkans is also considered by some historians to have delayed the launch of the invasion of the Soviet Union by a critical month, which proved disastrous when the German Army failed to take Moscow.

Greece was occupied and divided between Germany, Italy, and Bulgaria, while the King and the government fled into exile in Egypt. First attempts at armed resistance in summer 1941 were crushed by the Axis powers, but the Resistance movement began again in 1942 and grew enormously in 1943 and 1944, liberating large parts of the country's mountainous interior and tying down considerable Axis forces. Political tensions between the Resistance groups broke out in a civil conflict among them in late 1943, which continued until the spring of 1944. The exiled Greek government also formed armed forces of its own, which served and fought alongside the British in the Middle East, North Africa, and Italy. The contribution of the Greek Navy and merchant marine, in particular, was of special importance to the Allied cause[citation needed].

Mainland Greece was liberated in October 1944 with the German withdrawal in the face of the advancing Red Army, while German garrisons held out in the Aegean Islands until after the war's end. The country was devastated by war and occupation, and its economy and infrastructure lay in ruins. Greece suffered at least 250,000 dead during the Axis occupation,[1] and the country's Jewish community was almost completely exterminated in the Holocaust. By 1946, a civil war erupted between the foreign-sponsored conservative government and leftist guerrillas, which lasted until 1949.

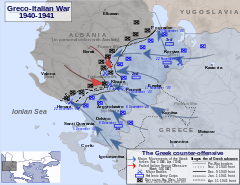

The Italian invasion from Albania on October 28, 1940, after making small initial gains, was stopped by the determined defense of Greek forces in the battles at the Elaia–Kalamas line and the Pindus Mountains. The unwillingness of Bulgaria to attack Greece, as the Italians had hoped, allowed the Greek High Command to transfer most of the mobilizing divisions intended for the garrisoning of Macedonia to the front, where they were instrumental in the Greek counteroffensive, launched on November 14. Greek forces crossed the border into Albania and took city after city despite facing a harsh winter, having inadequate supplies and facing Italian air superiority. By mid-January, Greek forces had occupied a quarter of Albania, but the offensive came to a standstill before it reached its objective, the port of Vlorë.

This situation prompted Germany to come to the rescue of its Axis partner. According to Stockings and Hancock, Hitler had never wished to interfere in the Balkans. They claim in their book, Swastika over the Acropolis (2013) that the invasion of Greece had more to do with "a reluctant response to British involvement" than aiding his Axis partner.[2] In a final attempt to restore Italian prestige before the German intervention, a counterattack was launched on March 9, 1941, against the key sector of Klissura, under Mussolini's personal supervision. Despite massive artillery bombardments and the employment of several divisions on a narrow front, the attack made no headway and was called off in under two weeks.

But by April 13, the Italian front in Albania finally began to move, prompted by the general Italo-German joint attack. The Greeks put up a strong defense, fighting vigorously. A few days later, they retreated and lost much of their hard-won Albanian territory. Italian Bersaglieri units appeared and entered the plain of Korce, but even though minefields and road-blocks tried to delay their passage into Greek territory, they simply dismounted from their lorries and continued advancing by bicycle. The Greek Army of the Epirus was exhausted, while "the Italian advance amounted merely to keeping up with a defeated and retreating enemy".[3]

|

|

| Italian invasion and initial Greek counter-offensive 28 October – 18 November 1940 |

Greek counter-offensive and stalemate 14 November 1940 – 23 April 1941 |

The long-anticipated German attack (Unternehmen Marita) began on April 6, 1941, against both Greece and Yugoslavia. The resulting "Battle of Greece" ended with the fall of Kalamata in the Peloponnese on April 30, the evacuation of the Commonwealth Expeditionary Force and the complete occupation of the Greek mainland by the Axis.

The initial attack came against the Greek positions of the "Metaxas Line" (19 forts in Eastern Macedonia between Mt. Beles and River Nestos and 2 more in Western Thrace). It was launched from Bulgarian territory and supported by artillery and bomber aircraft. The resistance of the forts under general Konstantinos Bakopoulos was both courageous and determined, but eventually futile. The rapid collapse of Yugoslavia had allowed the 2nd Panzer Division (which had started from the Strumica Valley in Bulgaria, advanced through Yugoslav territory and turned south along the Vardar/Axios River valley) to bypass the defenses and capture the vital port city of Thessaloniki on April 9. As a result, the Greek forces manning the forts (the Army Section of Eastern Macedonia, TSAM[4]) were cut off and given permission to surrender by the Greek High Command. The surrender was completed the next day, April 10, the same day that German forces crossed the Yugoslav-Greek border near Florina in Western Macedonia, after having defeated any resistance in southern Yugoslavia. The Germans broke through the Commonwealth (2 div. & 1 arm. brig.) and Greek (2 div.) defensive positions in the Kleidi area on April 11/12, and moved on to the south and southwest.

While pursuing the British southward, the southwest movement threatened the rear of the bulk of the Greek Army (14 divisions), which faced the Italians at the Albanian front. The Army belatedly began retreating southward, first its northeast flank on April 12, and finally the southwest flank on April 17. The German thrust to Kastoria on April 15 made the situation critical, threatening to cut the Greek retreat. The generals at the front began exploring the possibilities for capitulation (to the Germans only), despite the High Command's insistence on continuing the fight to cover the British retreat.

In the event, several generals under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Georgios Tsolakoglou mutinied on April 20, and taking matters in their own hands, signed a protocol of surrender with the commander of the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) near Metsovo the same day. It was followed by a second in Ioannina the next day (with Italian representation this time) and a final one in Thessaloniki between the three combatants on the 23rd. The very same day in Athens, Lt. General A. Papagos resigned his office as Supreme Commander whereas the King and his government embarked for Crete. About the same time the Commonwealth forces made a last stand at Thermopylae before their final retreat to the ports of Peloponnese for evacuation to Crete or Egypt. German troops seized the Corinth Canal bridges, entered Athens on April 27, and completed their occupation of the mainland and most islands by the end of the month, along with the Italians and Bulgarians.

The only Greek territory remaining free by May 1941 was the large and strategically important island of Crete, which was held by a large but weak Allied garrison consisting primarily of the combat-damaged units evacuated from the mainland without their heavy equipment, especially transport. To conquer it, the German High Command prepared "Unternehmen Merkur", the first mass-scale airborne operation in history.

The attack was launched on May 20, 1941. The Germans attacked the three main airfields of the island, at the northern towns of Maleme, Rethimnon, and Heraklion, with paratroopers and gliders. The Germans met stubborn resistance from the British, Australian, New Zealand and the remaining Greek troops on the island, and from local civilians. At the end of the first day, none of the objectives had been reached.

The next day, partly through miscommunication and the Allied commanders' failure to grasp the situation, Maleme airfield in western Crete fell to the Germans. With Maleme airfield secured, the Germans flew in thousands of reinforcements and captured the rest of the western side of the island. This was followed by severe British naval losses due to intense German air attacks around the island. After seven days of fighting the Allied commanders realized that victory was no longer possible. By June 1, the evacuation of Crete by the Allies was complete and the island was under German occupation. In light of the heavy casualties suffered by the elite 7th Flieger Division, Adolf Hitler forbade further large-scale airborne operations. General Kurt Student dubbed Crete "the graveyard of the German paratroopers" and its fall "a disastrous victory".[5]

Immediately after the fall of Crete, Gen. Student ordered a wave of reprisals against the local population (Kondomari, Alikianos, Kandanos, etc.). The reprisals were carried out rapidly, omitting formalities and by the same units who had been confronted by the locals. Very soon, the Cretans formed resistance groups and in cooperation with British SOE agents began to harass the German forces with considerable success till the end of the war. As a result, mass reprisals against civilians continued throughout the occupation (Heraklion, Viannos, Kali Sykia, Kallikratis, Damasta, Kedros, Anogeia, Skourvoula, Malathyros, etc.).

The Greek government claimed in 2006 that the Greek Resistance killed 21,087 Axis soldiers (17,536 Germans, 2,739 Italians, 1,532 Bulgarians) and captured 6,463 (2,102 Germans, 2,109 Italians, 2,252 Bulgarians), for the death of 20,650 Greek partisans and an unknown number captured.[6] According to the OKH Heeresarzt 10-Day Casualty Reports per Theater of War, 1944,[7] the German field army had 8,152 dead, 22,794 wounded and 8,222 missing in the South- East (Greece and Yugoslavia) between 22 June 1941 and 31 December 1944. According to the OKW monthly casualty reports,[8] German army losses in the same theater between June 1941 and December 1944 were 16,532 dead (1.6.1941 to 31.12.1944), 22,794 wounded and sick (22 June 1941 to 31 December 1944) and 13,838 missing (1 June 1941 to 31 December 1944). Most German casualties in the South-East occurred in Yugoslavia.[9] The German War Graves Commission maintains two German cemeteries on Greek territory, one at Maleme on Crete containing 4,468 dead (mainly from the Battle of Crete), and another at Dionyssos-Rapendoza, containing about 10,000 dead transferred there from all over Greece except Crete.

The aforementioned Greek government report (p. 126) claims that the population losses of Greece in World War 2 were 1,106,922, thereof 300,000 due to birth deficit and 806,922 due to mortality. Deaths are broken down as follows: military deaths in 1940/41, 13,327; executed, 56,225; died as hostages in German concentration camps, 105,000; deaths from bombing, 7,000; national resistance fighters, 20,650; deaths in the Middle East, 1,100; deaths in the merchant navy, 3,500 (subtotal: 206,922); deaths from hunger and related diseases, 600,000. Included in the number of concentration camp victims are 69,151 Greek Jews deported between 15 March 1943 and 10 August 1944, of whom only 2,000 returned (p. 68). The number of 600,000 victims of the "great hunger" is mentioned in the entry dated 5 February 1942 of a "short diary of the resistance" (p. 118). An estimated 300,000 people died in the Great Famine (Greece) in 1941–1944.

BBC News estimates Greece suffered at least 250,000 dead during the Axis occupation.[1] Historian William Woodruff lists 155,300 dead Greek civilians and 16,400 military deaths,[10] while David T. Zabecki lists 73,700 battle deaths and 350,000 civilian deaths.[11]

Conquered Greece was divided into three zones of control by the occupying powers, Germany, Italy and Bulgaria.[12] The Germans controlled Athens, Central Macedonia, Western Crete, Milos, Amorgos and the islands of the Northern Aegean. Bulgaria annexed Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia, while Italy occupied approximately two thirds of the country. The Italians were thus responsible for the greater part of Greece, especially the countryside, where any armed Resistance might take place. Italian forces in Greece comprised 11 infantry divisions, grouped in the 11th Army under General Carlo Geloso,[13] with a further division in the Italian colony of the Dodecanese Islands. Until the summer of 1942, as the Resistance movement was in its infancy, they faced little opposition and considered the situation normalized.[14] The Germans limited themselves during the first period of the Occupation to the strategically important areas, and their forces were limited. The German troops in southeastern Europe came under the 12th Army headed initially by Field Marshal Wilhelm List and later by General Alexander Löhr. In Greece, two separate commands were created: the Salonica-Aegean Military Command at Thessalonica and the Southern Greece Military Command at Athens, for the entire duration of the war under Luftwaffe General Hellmuth Felmy.[15] Crete was organized as a fortress ("Festung Kreta") garrisoned by the Fortress Division "Kreta", and after August garrisoned by the crack 22nd Air Landing Division. The Bulgarians occupied their own zone with an Army Corps and, faced with active resistance from the local population, engaged from the outset in a policy of Bulgarization of the area.

After mid-1942, with the growth of armed Resistance, and the spectacular destruction of the Gorgopotamos bridge (Operation "Harling") by a force of Greek guerrillas and British saboteurs on 25 November, the Italian authorities tried vainly to contain the surge in acts of resistance directed against their forces. The guerrillas were largely successful against the Italians, allowing for the creation of "liberated" areas in the mountainous interior, including sizeable towns, by mid-1943. At that time, German troops began moving into Greece. Elite formations such as the 1st Panzer Division and the 1st Mountain Division were brought into the country, both in anticipation of a possible Allied landing in Greece (a concept deliberately promoted by the Allies themselves as a diversion from the landings at Sicily) and as a guarantee against a possible Italian capitulation.[16]

These forces, especially the experienced mountain troops, engaged in large-scale counter-guerrilla operations in the area of Epirus. Their operations were successful in that they reduced the threat of guerrilla attacks on the occupation forces, but their often brutal conduct and mass reprisals policy resulted in massacres of civilians such as that of Kommeno on August 16, the Massacre of Distomo, or the "Massacre of Kalavryta" in December. In anticipation of the Italian collapse, the German command structure throughout the Balkans was reorganized: Army Group E under Löhr took over in Greece, overseeing both German forces and the Italian 11th Army.[17]

The Italian capitulation in September caused most Italian units not to surrender to the Germans, although others, such as the Pinerolo division and the Lancieri di Aosta Cavalry Regiment, went over to the guerrillas, or chose to resist the German takeover. This resulted in a brief but violent clash between Germans and Italians, accompanied by atrocities against Italian prisoners of war, such as the massacre of the Acqui Division on Cephallonia, dramatized by the film Captain Corelli's Mandolin. In addition, British and Greek forces tried to occupy the Italian-held Dodecanese, but they and their Italian allies were defeated in a short campaign (see Dodecanese Campaign).[18]

Throughout late 1943 and the first half of 1944, the Germans, in cooperation with the Bulgarians and aided by Greek collaborators (see below) launched clearing operations against the Greek resistance, primarily against the communist-controlled "ELAS", while coming into an unofficial truce with the rightist EDES. At the same time, raids by British and Greek special forces were increasing in frequency in the Aegean islands. Finally, with the advance of the Red Army and the desertion of Romania and Bulgaria, the Germans evacuated mainland Greece in October 1944, although isolated garrisons remained in Crete, the Dodecanese and various other Aegean islands until the end of the war in May 1945.

As in some occupied European countries, a Greek puppet government was formed from the outset by the Occupation authorities, initially headed by General Georgios Tsolakoglou and later by Konstantinos Logothetopoulos. The forces this government had at its disposal were primarily these of the city police and the rural gendarmerie, which were relied upon to maintain and enforce order. The government could not extend its authority to all of the country, as on the one side it was never given free rein nor entirely trusted by its Axis overseers, nor was it popular among the people. As anti-Axis sentiment grew in 1942, its organs found themselves attacked by guerrillas and socially isolated. Except for isolated cases, such as the group of Colonel Georgios Poulos and Friedrich Schubert's Jagdkommando, only in 1943, with the appointment of the experienced politician Ioannis Rallis as Prime Minister, did the Germans allow any substantial Greek armed force to be recruited by the Athens government. These were the infamous "Security Battalions" (Tagmata Asfaleias), whose motivation, as in many other cases in occupied Europe, was primarily political: they fought exclusively against the communist-dominated EAM-ELAS resistance movement, which controlled most of the country. Their harsh and indiscriminate repressive activities against the population at large and their association with the Germans led to wide vilification and in colloquial Greek they were known as Germanotsoliades (Greek: Γερμανοτσολιάδες, literally meaning "German Tsolias").

After the fall of Greece to the Axis, elements of the Greek armed forces escaped to the British-controlled Middle East. There they were placed under the Greek government in exile, and continued the fight alongside the Allies. The Greek Armed Forces in the Middle East fought on the North African Campaign, the Italian Campaign most notably in the Battle of Rimini, the Dodecanese Campaign and commando raids against German positions in Greece, and participated in convoy duties in the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean. Greek navy participated in the Operation Overlord at Normandy.[19][20][21][22]

As in Greece, these forces were plagued by political strife, culminating in the pro-EAM April 1944 mutiny. After its suppression, the armed forces were restructured along firmly royalist and conservative officer cadres. Upon the withdrawal of German forces from the Greek mainland in October 1944, they returned to Greece and formed the nucleus of the new Greek armed forces that fought against EAM in the Dekemvriana, and against the Communists during the Greek Civil War.

After the war, Greece was in political and economic crisis due to the German occupation and the highly polarized struggle between leftists and rightists which targeted the power vacuum and led to the Greek Civil War, one of the first conflicts of the Cold War.

Officially, Greece claimed the lands of Northern Epirus (from Albania), Northern Thrace (from Bulgaria) and the Dodecanese from Italy, but gained only the Dodecanese, as the new communist-controlled governments of Albania and Bulgaria had Soviet support.

After the war, the official Greek state tried and executed for war crimes among others Andon Kalchev, Bruno Bräuer, Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller and Friedrich Schubert. Nevertheless, most perpetrators of such crimes were never punished.

The Axis occupation of Greece, specifically the Greek islands, figures in several English-language books and films based on real special forces raids such as Ill Met by Moonlight, The Cretan Runner, fictional ones like The Guns of Navarone, Escape to Athena, The Magus, They Who Dare, and Captain Corelli's Mandolin (a fictional occupation narrative). Notable Greek movies referring to the period, the war and the occupation, are Ochi, What did you do in the war, Thanasi? and Ipolochagos Natassa.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)