Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

The government of India constituted a common tribunal on 10 April 1969 to adjudicate the river water utilization disputes among the river basin states of Krishna and Godavari rivers under the provisions of Interstate River Water Disputes Act – 1956.[1] The common tribunal was headed by Sri RS Bachawat as its chairman with Sri DM Bhandari and Sri DM Sen as its members. Krishna River basin states Maharashtra, Karnataka and old Andhra Pradesh insisted on the quicker verdict as it had become more expedient for the construction of irrigation projects in Krishna basin.[2] So the proceedings of Krishna Water Disputes Tribunal (KWDT) were taken up first separately and its final verdict was submitted to GoI on 27 May 1976.[3]

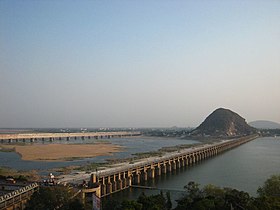

The Krishna River is the second biggest river in peninsular India. It originates near Mahabaleshwar in Maharashtra and runs for a distance of 303 km in Maharashtra, 480 km through the breadth of North Karnataka and the rest of its 1300 km journey in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh before it empties into the Bay of Bengal.

The river basin[4] is 257,000 km2 and the States of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh contributes 68,800 km2 (26.8%), 112,600 km2 (43.8%) and 75,600 km2 (29.4%) respectively.[5]

The Bachawat commission (KWDT I) went over the matter in detail and gave its final award in 1973. While the Tribunal had in its earlier report detailed two schemes, Scheme A and Scheme B, the final award only included Scheme A and Scheme B was left out. Scheme A pertained to the division of the available waters based on 75% dependability, while Scheme B recommended ways to share the surplus waters.

The government took another three years to publish the award in its Extraordinary Gazette dated 31 May 1976. With that the final award (Scheme A) of the KWDT became binding on the three states.

The KWDT in its award outlined the exact share of each state. The award contended based on 75% dependability that the total quantum of water available for distribution was 2060TMC. This was divided between the three states in the following manner.

| Maharashtra | 560 TMC |

| Karnataka | 700 TMC |

| Telangana & Andhra Pradesh | 800 TMC |

In addition to the above, the states were allowed to use regeneration/return flows to the extent of 25, 34 and 11 TMC respectively subject to time-bound usage of allocated water out of 2060 TMC total allocation as stated in clause V of the KWDT-1 final order. Further, the Tribunal has allowed the States to utilize their allocated share of water for any project as per their plans. As per clauses V & VII of the final order of KWDT-1, a state can fully use its allocated water in any water year (in case of a deficit water year also) by utilizing the carryover storage facility. A state can create carryover storage during the years when water yield in the river is in excess of 2060 TMC plus entitled return flows to use in the water year when water yield in the river is less than total entitlement (nearly 2130 TMC). Thus KWDT-1[6] allocated water use from the river up to 2130 TMC at 100% success rate out of average yield in the river and not subject to water availability in a 75% dependable year.[7] The average yield in the river is assessed as 2578 TMC by recent KWDT-2. Moreover, the last riparian state (erstwhile AP state) was permitted by KWDT-I to utilize the surplus unallocated water for use till the unallocated water is apportioned to riparian states by a new tribunal award after its gazette notification by the Union Government.

River water availability and water use measurements criteria in a water year are identical for both the Krishna River and Godavari River tribunal awards except for outside the river basin uses.

Including regeneration, the total water available to Karnataka for utilization is nearly 734 TMC. Out of this, Upper Krishna Project has been allotted 173 TMC.[8][9]

The tribunal in its report, under Scheme B, has determined that the surplus water available in the river basin totalled 330 TMC. It was decided that this would be divided among the riparian states of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh in the ratio of 25%, 50% and 25% respectively. Scheme B also stipulates that the Krishna waters shall be shared in proportion to the Scheme A allotments when available water in the river is less than 2060 TMC in a water year.

The tribunal also made it clear that in case any one of the states were not to co-operate in sharing surplus water in the above ratio, Parliament should take a decision to distribute the surplus water through en enactment (Page 163 KWDT report Vol.II).

However, Scheme B involved the constitution of an authority (Krishna River Valley Authority) to ensure the implementation of the scheme. The constitution of such an authority, though, was outside the powers of the tribunal under the Inter State Water Disputes Act of 1956. As a result, Scheme B was left out of the Tribunal's final award and Scheme A alone was presented to the government for final notification in the Gazette.[10]

Therefore, for the time being, Andhra Pradesh has been given liberty [clause V(C) of KWDT −1] to make use of any surplus waters though it cannot claim any rights over the same.

The KWDT-1 provided for a review of its award after 31 May 2000. However no such review was taken up for more than 3 years after that.

In April 2004, the second KWDT, was constituted by the Government of India following requests by all three states. This tribunal has started its proceedings from 16.07.07.

The second Krishna Water Dispute Tribunal gave its draft verdict on 31 December 2010.[11] The allocation of available water was done according to 65% dependability, considering the records of flow of water for past 47 years. According to KWDT II, Andhra Pradesh got 1001 TMC of water, Karnataka 911 TMC and Maharashtra 666 TMC. Next review of water allocations will be after the year 2050.[12]

KWDT-2 has allocated entire average water (2578 TMC) yield in the river among states except 16 TMC which is to be let downstream of Prakasam Barrage near Vijayawada to the Sea as minimum environmental flows. There is no water allocation for the purpose of salt export to the sea. When rain water comes in contact with the soil, it picks up some salts in dissolved form from the soil. The total amount of dissolved salts contained in the river water has to reach sea without accumulating in the river basin. This process is called "salt export". If all the water is utilised without letting adequate water to the Sea, the water salinity / total dissolved salts (TDS) would be so high making it unfit for human, cattle and agriculture use.[13] Higher Sodium[14] in comparison with Calcium and Magnesium elements or presence of residual sodium carbonate in irrigation water would convert the agriculture lands into fallow sodic alkaline soil.[15] The low lands of Andhra Pradesh would be effected by alkalinity and salinity if adequate salt export is not taking place.[16]

The uplands of Krishna River basin located in Maharashtra and Karnataka are situated on the Deccan Traps which comprises thick seems of basalt rock formations.[17] Basalt rock is prone to chemical weathering contributing more TDS to the river water. Water is not safe for drinking if the TDS exceeds 500 mg/L. The average yearly salt export requirement is nearly 12 million tons in Krishna basin area up to Prakasam Barrage. At least 850 TMC water is required for salt export[18] purpose to maintain water TDS below 500 mg/L. This is including 360 TMC of Krishna River water being used outside the Krishna basin in AP. This water used outside the basin area is also serving the salt export purpose since salts are transferred outside the basin. Thus another 490 TMC is to be let to the sea for salt export purpose. If salt export and environmental[19] needs are considered, no further water allocation is feasible by KWDT-2 in excess of water use allocations made by KWDT-1 earlier.[20] Ultimately, the Krishna River basin would be net importer of water from the adjoining rivers such as Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh and west flowing rivers in Karnataka. Then the total salt load generated in Krishna basin shall be discharged directly into the Sea by releasing more than 850 tmc water to the downstream of Prakasam Barrage to maintain water salinity below 500 ppm.[citation needed]

Subject to all riparian states agreement not to use groundwater as an alternative source to surface water resource (i.e. to use groundwater sparingly), KWDT-1 excluded groundwater use from the beneficial uses for which Krishna River water allocations were made. Ground water exploitation has increased many folds in last 35 years. KWDT-2 has not deliberated how the ever increasing ground water use is diminishing the inflows in the river and the river water quality. The water allocation by KWDT-1 itself is 83% of 2578 TMC total water availability. During the decade/years 1998–2007, 510 TMC on an average per year was discharged into sea after utilising 1892 TMC out of 2402 TMC annual average yield (page 303 of KWDT-2) in the river which is only 21% of total yield. Already the multi year average TDS of Krishna water is around 450 mg/L which is close to safe maximum of 500 ppm.[21] The actual average water availability in the decade (years 1998 to 2007) is less by 176 TMC to the 2578 TMC estimated average water availability by KWDT-2. If full water utilisation as permitted by KWDT-1 to the extent of 2130 TMC is achieved in future, the usage would be 88.67% of 2402 TMC water availability which would increase the water salinity to unacceptable level. Thus there is no additional water available in the river for further allocation to the riparian states by KWDT-2 in excess of 2130 TMC on average permitted by KWDT-1. In fact, the KWDT-1 water use allocations are already in excess of the sustainable water use from the river when moderate environmental flow requirements are to be taken care.[22]

Unplanned water utilisation in Murray-Darling River basin in Australia has enhanced the alkalinity and salinity of river water beyond safe limits which is affecting the long-term sustainable productivity of the river basin.[23][24] So Murray-Darling Basin Authority is established to take up remedial action plan for recovering the damage occurred to the sustainable productivity of the river basin. Water quality and salinity management is made part of this plan. It has stipulated that water TDS limit of 500 mg/L (800 μS/cm) on daily basis should not exceed 95% of the duration in a year.[25] It has altered existing water use/entitlement of irrigation to enhance the environmental flows required for salt export.

Another example of river water sharing taking into account the water salinity is Colorado River[26] flowing in USA and Mexico. The 1944 United States-Mexico Treaty for Utilization of waters of the Colorado allots to Mexico a guaranteed annual quantity of water from the river. The treaty does not provide specifically for water quality, but this did not constitute a problem until the late 1950s. Rapid economic development and increased agricultural water use in the United States spurred degradation of water quality received by Mexico. With a view to resolving the problem, Mexico protested and entered into bilateral negotiations with the United States. In 1974, these negotiations resulted in an international agreement, interpreting the 1944 Treaty, which guaranteed Mexico water of the same quality as that being used in the United States. Sustainable Groundwater Management Act is also made in the year 2014 to avert the unsustainable ground water use or ground water mining in the state of California.

Already the water utilisation[27] in Krishna river basin is touching the maximum limit constricting the salt export to the Sea. Detailed study shall be conducted by experts to decide the minimum water needed for the salt export to the sea.[28] India should learn from the bad experience of Australia in over exploiting the waters of Murray-Darling River. Krishna Basin Authority in line with Murray-Darling Basin Authority shall be constituted by the Indian Government rejecting archaic river water allocations by the KWDT-2. Krishna Basin Authority should be headed by a panel of experts representing environment, irrigation, agriculture, ground water, geology, health, ecology, etc. to protect the river basin area for its long term sustainable productivity and ecology.[29][30] Hydrological transport model studies shall be conducted to find out the further possible pollution loads for alkalinity, pH, salinity, RSC index, etc.

In response to the special leave petition lodged by AP, Supreme Court directed the GoI[31] on 15 September 2011 not to accept the KWDT – II final verdict till it is re-examined by it for any violation of Interstate River Water Disputes Act 1956[32](amended last in the year 2002).

Cauvery water disputes tribunal order was notified by the GoI on 20 February 2013.[33] The tribunal has assessed 740 tmcft total water availability in a normal year from the river basin. During normal years, 192 tmcft is to be released by Karnataka to Tamil Nadu on monthly basis throughout the year. 192 tmcft is nearly equal to 37% of the water available from the upstream basin area in Karnataka and Kerala states. It also provides for proportionate eligibility of the water available from the river basin during the below normal yield years. Similarly, Krishna basin waters are to be allocated to the downstream state Andhra Pradesh from upstream states Karnataka and Maharashtra on monthly basis by KWDT-II.

Justice Brijesh Kumar tribunal gave its final/further verdict[34] on 29 November 2013 which has not changed the broad water allocations (except increasing the Andhra Pradesh allocations by 4 tmc with corresponding reduction in Karnataka allocations) for use by the states as given in its draft verdict.[35] The average yearly water available for environmental flows and the salt export has been reduced by KWDT-II to 171 tmc (including 16 tmc minimum continuous environmental flows) from 448 tmc giving 277 tmc additional allocations to the states for their beneficial use.[36] There is no mention or discussion on mean annual environmental flow requirement and the salt export water needs which have been taking place time immemorial and have been considered not essential needs by the tribunal disregarding the sustainable productivity and the ecology of the river basin particularly in the tail end areas.[37]

GoI extended the term of KWDT-2 by two years with effect from 1-8-2014 to adjudicate on fresh terms of references as stated in Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2014.[38]

Under this legislation by the Parliament, the KWDT II is extended with the terms of reference to make project-wise specific allocation, if such allocation have not been made earlier and to determine an operational protocol for project-wise release of water in the event of deficit flows.[39]

The above bill[40] also creates Krishna River Management Board located its headquarters in Seemandhra or Andhra Pradesh state with following functions

After nearly 7 years, the KRMB is notified by the central govt, after AP filed a writ petition in Supreme Court, as an autonomous body and its project wise functions are identified.[41][42]

The newly formed Telangana state is fourth riparian state in the Krishna River basin. The state wants the central government to start again the tribunal proceeding afresh as it was not party to the earlier KWDT1 and KWDT2 adjudications.[43] Karnataka and Maharashtra are opposing the tribunal proceeding afresh and stated that the extension of the tribunal period is only for resolving the water disputes between Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states.[44] The extended KWDT2 decided to confine redistribution of water between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh states only.[45][46] After a long gap, the central government decided for tribunal adjudication on Krishna river water's sharing dispute between the two states.[47]

On the request of Telangana state, the Union Government issued fresh terms of reference to KWDT2 superseding its earlier verdict of distributing unallocated water among all riparian states. As per the latest terms of reference dated 6 October 2023, the unallocated water of KWDT1 is to be distributed between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh states only.[48]

Water import from other rivers to the Krishna basin is governed by clause XIV B of the final order of KWDT I in the absence of any agreement between the riparian states. Recently, Andhra Pradesh started transfer of Godavari water through Polavaram right bank canal with the help of Pattiseema lift for the water use in Krishna delta, etc.[49] Telangana state is also transferring and using Godavari water for the needs of Hyderabad city water supply from Singoor project, Manjira project and Yellampalli projects. 80% of the Godavari water used for the requirements of Hyderabad city is available as regenerated water and is being used for irrigation purpose in Krishna basin area of Telangana as per clause VII A of the final order of KWDT I.[1] Also, Telangana state is transferring Godavari water from Sriram Sagar and Devadula projects for irrigation purpose in its Krishna basin area. Pranahita Chevella lift irrigation scheme, Dummugudem Lift Irrigation Scheme in Telangana are also under construction to transfer additional Godavari water to its Krishna basin area. Karnataka is also constructing projects to transfer Mandovi and Netravati rivers water to its Krishna basin area.[50] A new tribunal is to be constituted to resolve the sharing of additional water available in the river basin among the riparian states as per clause XIV B of the final order of KWDT I.[1]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)