Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| South Asia | ~30–43 million (c. 2009/10) |

| Languages | |

| Braj • Hindi • Haryanvi • Khariboli • Punjabi (and its dialects) • Rajasthani • Sindhi (and its dialects) • Urdu | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism • Islam • Sikhism | |

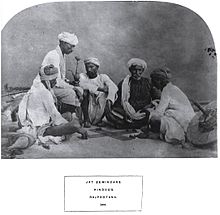

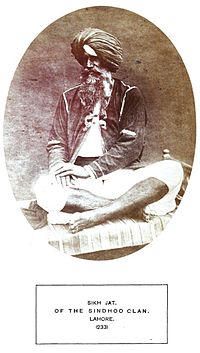

The Jat people, also spelt Jaat and Jatt,[1] are a traditionally agricultural community in Northern India and Pakistan.[2][3][4][a][b][c] Originally pastoralists in the lower Indus river-valley of Sindh, many Jats migrated north into the Punjab region in late medieval times, and subsequently into the Delhi Territory, northeastern Rajputana, and the western Gangetic Plain in the 17th and 18th centuries.[8][9][10] Of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh faiths, they are now found mostly in the Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan and the Pakistani regions of Sindh, Punjab and AJK.

The Jats took up arms against the Mughal Empire during the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[11] Gokula, a Hindu Jat landlord was among the earliest rebel leaders who fought against the Mughal rule during Aurangzeb's era.[12] The Hindu Jat kingdom reached its zenith under Maharaja Suraj Mal (1707–1763).[13] The community played an important role in the development of the martial Khalsa panth of Sikhism.[14] By the 20th century, the landowning Jats became an influential group in several parts of North India, including Punjab,[15] Western Uttar Pradesh,[16] Rajasthan,[17] Haryana and Delhi.[18] Over the years, several Jats abandoned agriculture in favour of urban jobs, and used their dominant economic and political status to claim higher social status.[19] On 13 April, International Jat Day is celebrated every year all around the world.[20][21]

The Jats are a paradigmatic example of community- and identity-formation in early modern Indian subcontinent.[8] "Jat" is an elastic label applied to a wide-ranging community[22][23] from simple landowning peasants [a][b][c][24][25][d] to wealthy and influential Zamindars.[27][28][29][30][31]

A female Jat is often known as Jatni.[32]

By the time of Muhammad bin Qasim's conquest of Sind in the eighth century, Arab writers described agglomerations of Jats, known to them as Zutt, in the arid, the wet, and the mountainous regions of the conquered land of Sindh.[33] The Arab rulers, though professing a theologically egalitarian religion, maintained the position of Jats and the discriminatory practices against them that had been put in place in the long period of Hindu rule in Sind.[34] Between the eleventh and the sixteenth centuries, Jat herders at the Sind migrated up along the river valleys,[35] into the Punjab,[8] which may have been largely uncultivated in the first millennium.[36] Many took up tilling in regions such as western Punjab, where the sakia (water wheel) had been recently introduced.[8][37] By early Mughal times, in the Punjab, the term "Jat" had become loosely synonymous with "peasant",[38] and some Jats had come to own land and exert local influence.[8] The Jats had their origins in pastoralism in the Indus valley, and gradually became agriculturalist farmers.[39] Around 1595, Jat Zamindars controlled a little over 32% of the Zamindaris in the Punjab region.[40]

According to historians Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot,[41]

The Jats also provide an important insight into how religious identities evolved during the precolonial era. Before they settled in the Punjab and other northern regions, the pastoralist Jats had little exposure to any of the mainstream religions. Only after they became more integrated into the agrarian world did the Jats adopt the dominant religion of the people in whose midst they dwelt.[41]

Over time the Jats became primarily Muslim in the western Punjab, Sikh in the eastern Punjab, and Hindu in the areas between Delhi Territory and Agra, with the divisions by faith reflecting the geographical strengths of these religions.[41] During the decline of Mughal rule in the early 18th century, the Indian subcontinent's hinterland dwellers, many of whom were armed and nomadic, increasingly interacted with settled townspeople and agriculturists. Many new rulers of the 18th century came from such martial and nomadic backgrounds. The effect of this interaction on India's social organization lasted well into the colonial period. During much of this time, non-elite tillers and pastoralists, such as the Jats or Ahirs, were part of a social spectrum that blended only indistinctly into the elite landowning classes at one end, and the menial or ritually polluting classes at the other.[42] During the heyday of Mughal rule, Jats had recognized rights. According to Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf:

Upstart warriors, Marathas, Jats, and the like, as coherent social groups with military and governing ideals, were themselves a product of the Mughal context, which recognized them and provided them with military and governing experience. Their successes were a part of the Mughal success.[43]

As the Mughal empire faltered, there were a series of rural rebellions in North India.[44] Although these had sometimes been characterized as "peasant rebellions", others, such as Muzaffar Alam, have pointed out that small local landholders, or zemindars, often led these uprisings.[44] The Sikh and Jat rebellions were led by such small local zemindars, who had close association and family connections with each other and with the peasants under them, and who were often armed.[45]

These communities of rising peasant-warriors were not well-established Indian castes,[46] but rather quite new, without fixed status categories, and with the ability to absorb older peasant castes, sundry warlords, and nomadic groups on the fringes of settled agriculture.[45][47] The Mughal Empire, even at the zenith of its power, functioned by devolving authority and never had direct control over its rural grandees.[45] It was these zemindars who gained most from these rebellions, increasing the land under their control.[45] The triumphant even attained the ranks of minor princes, such as the Jat ruler Badan Singh of the princely state of Bharatpur.[45]

In 1669, the Hindu Jats, under the leadership of Gokula, rebelled against the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in Mathura.[48] The community came to predominate south and east of Delhi after 1710.[49] According to historian Christopher Bayly

Men characterised by early eighteenth century Mughal records as plunderers and bandits preying on the imperial lines of communications had by the end of the century spawned a range of petty states linked by marriage alliance and religious practice.[49]

The Jats had moved into the Gangetic Plain in two large migrations, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries respectively.[49] They were not a caste in the usual Hindu sense, for example, in which Bhumihars of the eastern Gangetic plain were; rather they were an umbrella group of peasant-warriors.[49] According to Christopher Bayly:

This was a society where Brahmins were few and male Jats married into the whole range of lower agricultural and entrepreneurial castes. A kind of tribal nationalism animated them rather than a nice calculation of caste differences expressed within the context of Brahminical Hindu state.[49]

By the mid-eighteenth century, the ruler of the recently established Jat kingdom of Bharatpur, Raja Surajmal, felt sanguine enough about durability to build a garden palace at nearby Deeg.[50] According to historian, Eric Stokes,

When the power of the Bharatpur raja was riding high, fighting clans of Jats encroached into the Karnal/Panipat, Mathura, Agra, and Aligarh districts, usually at the expense of Rajput groups. But such a political umbrella was too fragile and short-lived for substantial displacement to be effected.[51]

When Arabs entered Sindh and other Southern regions of current Pakistan in the seventh century, the chief tribal groupings they found were the Jats and the Med people. These Jats are often referred as Zatts in early Arab writings. The Muslim conquest chronicles further point at the important concentrations of Jats in towns and fortresses of Lower and Central Sindh.[52][53] Today, Muslim Jats are found in Pakistan and India.[54]

While followers important to Sikh tradition like Baba Buddha were among the earliest significant historical Sikh figures, and significant numbers of conversions occurred as early as the time of Guru Angad (1504–1552),[55] the first large-scale conversions of Jats is commonly held to have begun during the time of Guru Arjan (1563–1606).[55][56]: 265 While touring the countryside of eastern Punjab, he founded several important towns like Tarn Taran Sahib, Kartarpur, and Hargobindpur which functioned as social and economic hubs, and together with the community-funded completion of the Darbar Sahib to house the Guru Granth Sahib and serve as a rallying point and center for Sikh activity, established the beginnings of a self-contained Sikh community, which was especially swelled with the region's Jat peasantry.[55] They formed the vanguard of Sikh resistance against the Mughal Empire from the 18th century onwards.

It has been postulated, though inconclusively, that the increased militarization of the Sikh panth following the martyrdom of Guru Arjan (beginning during the era of Guru Hargobind and continuing after) and its large Jat presence may have reciprocally influenced each other.[57][full citation needed][58]

At least eight of the 12 Sikh Misls (Sikh confederacies) were led by Jat Sikhs,[59] who would form the vast majority of Sikh chiefs.[60]

According to censuses in gazetteers published during the colonial period in the early 20th century, further waves of Jat conversions, from Hinduism to Sikhism, continued during the preceding decades.[61][62] Writing about the Jats of Punjab, the Sikh author Khushwant Singh opined that their attitude never allowed themselves to be absorbed in the Brahminic fold.[63][64] The British played a significant role in the rise of Sikh Jat population by encouraging Hindu Jats to convert to Sikhism so as to get larger number of Sikh recruits for their army.[65][66]

In Punjab, the states of Patiala,[67] Faridkot, Jind, and Nabha[68] were ruled by the Sikh Jats.

According to anthropologist Sunil K. Khanna, Jat population is estimated to be around 30 million (or 3 crore) in South Asia in 2010. This estimation is based on statistics of the last caste census and the population growth of the region. The last caste census was conducted in 1931, which estimated Jats to be 8 million, mostly concentrated in India and Pakistan.[69] Deryck O. Lodrick estimates Jat population to be over 33 million (around 12 million and over 21 million in India and Pakistan, respectively) in South Asia in 2009 while noting the unavailability of precise statistics in this regard. His estimation is based on a late 1980s population projection of Jats and the population growth of India and Pakistan. He also notes that some estimates put their total population in South Asia at approximately 43 million in 2009.[70]

In India, multiple 21st-century estimates put Jats' population share at 20–25% in Haryana state and at 20–35% in Punjab state.[71][72][73] In Rajasthan, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh, they constitute around 9%, 5%, and 1.2% respectively of the total population.[74][75][76]

In the 20th century and more recently, Jats have dominated as the political class in Haryana[77] and Punjab.[78] Some Jat people have become notable political leaders, including the sixth Prime Minister of India, Charan Singh[79] and the sixth Deputy Prime Minister of India, Chaudhary Devi Lal.[80]

Consolidation of economic gains and participation in the electoral process are two visible outcomes of the post-independence situation. Through this participation they have been able to significantly influence the politics of North India. Economic differentiation, migration and mobility could be clearly noticed amongst the Jat people.[81]

Jats are classified as Other Backward Class (OBC) in seven of India's thirty-six States and UTs, namely Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.[82] However, only the Jats of Rajasthan – excluding those of Bharatpur district and Dholpur district – are entitled to reservation of central government jobs under the OBC reservation.[83] In 2016, the Jats of Haryana organized massive protests demanding to be classified as OBC in order to obtain such affirmative action benefits.[82]

Many Jat Muslim people live in Pakistan and have dominant roles in public life in the Pakistani Punjab and Pakistan in general. Jat communities also exist in Pakistani-administered Kashmir, in Sindh, particularly the Indus delta and among Seraiki-speaking communities in southern Pakistani Punjab, the Kachhi region of Balochistan and the Dera Ismail Khan District of the North West Frontier Province.

In Pakistan also, Jat people have become notable political leaders, like Hina Rabbani Khar.[84]

Many Jat people serve in the Indian Army, including the Jat Regiment, Sikh Regiment, Rajputana Rifles and the Grenadiers, where they have won many of the highest military awards for gallantry and bravery. Jat people also serve in the Pakistan Army especially in the Punjab Regiment.[85]

The Jat people were designated by officials of the British Raj as a "martial race", which meant that they were one of the groups whom the British favoured for recruitment to the British Indian Army.[86][87] This was a designation created by administrators that classified each ethnic group as either "martial" or "non-martial": a "martial race" was typically considered brave and well built for fighting,[88] whilst the remainder were those whom the British believed to be unfit for battle because of their sedentary lifestyles.[89] However, the martial races were also considered politically subservient, intellectually inferior, lacking the initiative or leadership qualities to command large military formations. The British had a policy of recruiting the martial Indians from those who has less access to education as they were easier to control.[90][91] According to modern historian Jeffrey Greenhunt on military history, "The Martial Race theory had an elegant symmetry. Indians who were intelligent and educated were defined as cowards, while those defined as brave were uneducated and backward". According to Amiya Samanta, the martial race was chosen from people of mercenary spirit (a soldier who fights for any group or country that will pay him/her), as these groups lacked nationalism as a trait.[92] The Jats participated in both World War I and World War II, as a part of the British Indian Army.[93] In the period subsequent to 1881, when the British reversed their prior anti-Sikh policies, it was necessary to profess Sikhism in order to be recruited to the army because the administration believed Hindus to be inferior for military purposes.[94]

The Indian Army admitted in 2013 that the 150-strong Presidential Bodyguard comprises only people who are Hindu Jats, Jat Sikhs and Hindu Rajputs. Refuting claims of discrimination, it said that this was for "functional" reasons rather than selection based on caste or religion.[95]

Deryck O. Lodrick estimates religion-wise break-up of Jats as follows: 47% Hindus, 33% Muslims, and 20% Sikhs.[70]

Jats pray to their dead ancestors, a practice which is called Jathera.[96]

There are conflicting scholarly views regarding the varna status of Jats in Hinduism. Historian Satish Chandra describes the varna of Jats as "ambivalent" during the medieval era.[97] Historian Irfan Habib states that the Jats were a "pastoral Chandala-like tribe" in Sindh during the eighth century. Their 11th-century status of Shudra varna changed to Vaishya varna by the 17th century, with some of them aspiring to improve it further after their 17th-century rebellion against the Mughals. He cites Al-Biruni and Dabistan-i Mazahib to support the claims of Shudra and Vashiya varna respectively.[98]

The Rajputs refused to accept Jat claims to Kshatriya status during the later years of the British Raj and this disagreement frequently resulted in violent incidents between the two communities.[99] The claim at that time of Kshatriya status was being made by the Arya Samaj, which was popular in the Jat community. The Arya Samaj saw it as a means to counter the colonial belief that the Jats were not of Aryan descent but of Indo-Scythian origin.[100]

During the colonial period, many communities including Hindu Jats were found to be practicing female infanticide in different regions of Northern India.[101][102]

A 1988 study of Jat society pointed out that differential treatment is given to women in comparison to men. The birth of a male child in a family is celebrated and is considered auspicious, while the reaction to the birth of a female child is more subdued. In villages, female members are supposed to get married at a younger age and they are expected to work in fields as subordinate to the male members. There is general bias against education for the female child in society, though trends are changing with urbanisation. Purdah system is practiced by women in Jat villages which act as hindrance to their overall emancipation. The village Jat councils which are male-dominated mostly don't allow female members to head their councils as the common opinion on it is that women are inferior, incapable and less intelligent to men.[103]

The Jat people are subdivided into numerous clans, some of which overlap with the Ror,[104] Arain,[105] Rajput[105] and other groups.[106] Hindu and Sikh Jats practice clan exogamy.

Jats are part of Punjabi and Haryanvi culture and are often portrayed in Indian and Pakistani films and songs.

Notwithstanding social, linguistic, and religious diversity, the Jats are one of the major landowning agriculturalist communities in South Asia.

Jat: Sikhs' largest zat, a hereditary land-owning community

Jat: name of large agricultural caste centered in the undivided Punjab and western Uttar Pradesh

The Jats, who are numerically dominant in central and eastern Punjab, can be Hindu, Sikh, or Muslim; they range from powerful landowners to poor subsistence farmers, and were recruited in large numbers to serve in the British army.

The Jat power neat Agra and Mathura arose out of the rebellion of peasants under zamindar leadership, attaining the apex of power under Suraj Mal...it seems to have been an extensive replacement of Rajput by Jat zamindars...and the 'warlike Jats' (a peasant and zamindar caste).

n the Ganges Canal Tract of the Muzaffarnagar district where the landowning castes – Tagas, Jats, Rajputs, Sayyids, Sheikhs, Gujars, Borahs

The number of parganas with Jat zamindaris (Map 2) is surprisingly large and well spread out, though there are none beyond the Jhelum. They appear to be in two blocks, divided by a sparse zone between the Sutlej and the Sarasvati basin. The two blocks, in fact, represent two different segments of the Jats, the western one (Panjab) known as Jat (with short vowel) and the other (Haryanvi) as Jaat (with long vowel).

Out of the 45 parganas of the sarkars of Delhi, 17 are reported to have Jat Zamindars. Out of these 17 parganas, the Jats are exclusively found in 11, whereas in other 6 they shared Zamindari rights with other communities.

Muzaffar Alam's study of the akhbarat (news reports) and chronicles of the period demonstrates that Banda and his followers had wide support amongst the Jat zamindars of the Majha, Jalandhar Doab, and the Malwa area. Jat zamindars actively colluded with the rebels, and frustrated the Mughal faujdars or commanders of the area by supplying Banda and his men with grain, horses, arms, and provisions. This evidence suggests that understanding the rebellion as a competition between peasants and feudal lords is an oversimplification, since the groups affiliated with Banda as well as those affiliated with the state included both Zamindars and peasants.

Banda led predominantly the uprisings of the Jat zamindars.It is also to be noted that tha Jats were the dominant zamindar castes in some of the parganas where Banda had support. But Banda's spectacular success and the amazing increase in the strength of his army within a few months*6 does not cohere with the presence of a few Jat zamindaris…we can, however presume that the unidentified zamindars of our sources who rallied behind Banda were the small zamindars (mah'ks) and the Mughal assessees (malguzars). It is not without significance that they are almost invariably described as the zamindars of village (mauza and dehat). These zamindars were largely the Jats who had settled in the region for the last three or four centuries.

Guru Nanak's father- in-law, Mula Chonha, works as an administrator for the Jat landlord, Ajita Randawa. If we expand this train of thought and examine other Janamsakhi figures we can detect an interesting pattern…All of Nanak's immediate relatives were professional administrators for local or regional lords, including Jat masters. From this we can infer that Khatris did seem to occupy a position as a professional class and some Jats held the position of being landlords. There was clearly a professional services relationship between high-ranking Khatris and high-ranking Jats, and this seems indicative of the wider socio- economic relationship between Khatris and Jats in medieval Panjab.

Jatni ( female Jat ) , portrayed as stitching her own wedding clothes , personified the Victorian ideals both of morally superior rural handicraft production and of women's proper domestic work within a male - dominated lineage

The Jats have long been distinguished by their martial traditions and by the custom of retaining their hair uncut. The influence of these traditions evidently operated prior to the formal inauguration of the Khalsa.

The Jat's spirit of freedom and equality refused to submit to Brahmanical Hinduism and in its turn drew the censure of the privileged Brahmins ... The upper caste Hindu's denigration of the Jat did not in the least lower the Jat in his own eyes nor elevate the Brahmin or the Kshatriya in the Jat's estimation. On the contrary, he assumed a somewhat condescending attitude towards the Brahmin, whom he considered little more than a soothsayer or a beggar, or the Kshatriya, who disdained earning an honest living and was proud of being a mercenary.

Others were even more candid about the necessity-and feasibility -of 'creating' Sikhs for the army. One contributor to the Indian Army's Journal of the United Services Institute of India proposed a scheme that would change Hindus to Sikhs for the specific purpose of recruitment. To do this, the Sikh recruiting grounds would be extended and Hindu Jats encouraged to take the pahul (the conversion ritual to martial Sikhism)'. He went on to say that these latter might not be as good stuff as that procurable from the present Sikh centres but they would, if of good physique, compare favourably (as regards field service qualifications) with the weedy specimens sometimes enlisted'. In this officer's view, then, the army could 'encourage' Hindus to become Sikhs simply to increase their overall numbers.

The British policy of recruiting the Sikhs (due to the imperial belief that Sikhism is a martial religion) resulted in the spread of Sikhism among the Jats of undivided Punjab and conversion of the Singhs into the 'Lions of Punjab'.

While the rulers of Patiala were Jat Sikhs and not Rajputs, the state was the closest princely territory to Bikaner's northwest.

The passage to Delhi, however, lay through the cis–Sutlej states of Patiala, Jind, Nabha and Faridkot, a long chain of Jat Sikh states that had entered into a treaty of alliance with the British as far back as April 1809 to escape incorporation into the kingdom of their illustrious and much more powerful neighbour, 'the lion of Punjab' Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Hina Rabbani Khar was born on 19 November 1977 in Multan, Punjab, Pakistan in a Muslim Jat family.

The Rajputs, Jats, Dogras, Pathans, Gorkhas, and Sikhs, for example, were considered martial races. Consequently, the British labored to ensure that members of the so-called martial castes dominated the ranks of infantry and cavalry and placed them in special "class regiments."

Apart from their physique, the martial races were regarded as politically subservient or docile to authority

The Saturday review had made much the same argument a few years earlier in relation to the armies raised by Indian rulers in princely states. They lacked competent leadership and were uneven in quality. Commander in chief Roberts, one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the martial race theory, though poorly of the native troops as a body. Many regarded such troops as childish and simple. The British, claims, David Omissi, believe martial Indians to be stupid. Certainly, the policy of recruiting among those without access to much education gave the British more semblance of control over their recruits.

Dr . Jeffrey Greenhunt has observed that " The Martial Race Theory had an elegant symmetry. Indians who were intelligent and educated were defined as cowards, while those defined as brave were uneducated and backward. Besides their mercenary spirit was primarily due to their lack of nationalism.

The Jats of the Panjab worship their ancestors in a practice known as Jathera.

The Marathas formed the fighting class in Maharashtra and also engaged themselves in agriculture. Like the Jats in north India, their position in the varna system was ambivalent.

A historically singular case is that of the Jatts, a pastoral Chandala-like tribe in eighth-century Sind, who attained sudra status by the eleventh century (Alberuni), and had become peasants par excellence (of vaisya status) by the seventeenth century (Dabistani-i Mazahib). The shift to peasant agriculture was probably accompanied by a process of 'sanskritization', a process which continued, when, with the Jat rebellion of the seventeenth century a section of the Jats began to aspire to the position of zamindars and the status of Rajputs.

The 1921 census reports classifies castes into two categories, namely, castes. having a tradition' of female infanticide and castes without such a tradition (see table). This census provides figures from 1901 to 1921 to show that in Punjab, United Provinces and Rajputana castes such as Hindu rajputs, Hindu jats and gujars with 'a tradition' of female infanticide had a much lower number of females per thousand males compared to castes without such a tradition which included: Muslim rajputs, Muslim jats, chamar, kanet, arain, kumhar, kurmi, brahmin, dhobi, teli and lodha

By 1850, several castes, in North India, the Jats, Ahirs, Gujars and Khutris, and the Lewa Patidar Kanbis in Central Gujarat were found to practice female infanticide. The colonial authorities also found that both in rural North and West India, the castes which practised female infanticide were propertied (they owned substantial arable land), had the hypergamous marriage norm and paid large dowries.

Ror clans: Sangwan, Dhiya, Malik, Lather, etc, are also found among the Jats. From an economic point of view the Rors living in Karnal and Kurukshetra districts consider themselves better off than their counterparts in Jind and Sonepat districts.

Some clans of the Arains which is also shared by Rajputs and the Jats. Bhutto is another variant of Bhutta. Some important Arian clans overlap with the Rajputs, for instance: Sirohsa, Ganja, Shaun, Bhatti, Butto, Chachar, Indrai, Joiya...