Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

Intelligence assessment, or simply intel, is the development of behavior forecasts or recommended courses of action to the leadership of an organisation, based on wide ranges of available overt and covert information (intelligence). Assessments develop in response to leadership declaration requirements to inform decision-making. Assessment may be executed on behalf of a state, military or commercial organisation with ranges of information sources available to each.

An intelligence assessment reviews available information and previous assessments for relevance and currency. Where there requires additional information, the analyst may direct some collection.

Intelligence studies is the academic field concerning intelligence assessment, especially relating to international relations and military science.

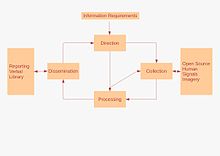

Intelligence assessment is based on a customer requirement or need, which may be a standing requirement or tailored to a specific circumstance or a Request for Information (RFI). The "requirement" is passed to the assessing agency and worked through the intelligence cycle, a structured method for responding to the RFI.

The RFI may indicate in what format the requester prefers to consume the product.

The RFI is reviewed by a Requirements Manager, who will then direct appropriate tasks to respond to the request. This will involve a review of existing material, the tasking of new analytical product or the collection of new information to inform an analysis.

New information may be collected through one or more of the various collection disciplines; human source, electronic and communications intercept, imagery or open sources. The nature of the RFI and the urgency placed on it may indicate that some collection types are unsuitable due to the time taken to collect or validate the information gathered. Intelligence gathering disciplines and the sources and methods used are often highly classified and compartmentalised, with analysts requiring an appropriate high level of security clearance.

The process of taking known information about situations and entities of importance to the RFI, characterizing what is known and attempting to forecast future events is termed "all source" assessment, analysis or processing. The analyst uses multiple sources to mutually corroborate, or exclude, the information collected, reaching a conclusion along with a measure of confidence around that conclusion.

Where sufficient current information already exists, the analysis may be tasked directly without reference to further collection.

The analysis is then communicated back to the requester in the format directed, although subject to the constraints on both the RFI and the methods used in the analysis, the format may be made available for other uses as well and disseminated accordingly. The analysis will be written to a defined classification level with alternative versions potentially available at a number of classification levels for further dissemination.

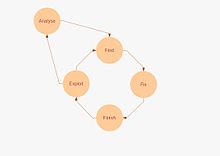

This approach, known as Find-Fix-Finish-Exploit-Assess (F3EA),[1] is complementary to the intelligence cycle and focused on the intervention itself, where the subject of the assessment is clearly identifiable and provisions exist to make some form of intervention against that subject, the target-centric assessment approach may be used.

The subject for action, or target, is identified and efforts are initially made to find the target for further development. This activity will identify where intervention against the target will have the most beneficial effects.

When the decision is made to intervene, action is taken to fix the target, confirming that the intervention will have a high probability of success and restricting the ability of the target to take independent action.

During the finish stage, the intervention is executed, potentially an arrest or detention or the placement of other collection methods.

Following the intervention, exploitation of the target is carried out, which may lead to further refinement of the process for related targets. The output from the exploit stage will also be passed into other intelligence assessment activities.

The Intelligence Information Cycle leverages secrecy theory and U.S. regulation of classified intelligence to re-conceptualize the traditional intelligence cycle under the following four assumptions:

Information is transformed from privately held to secretly held to public based on who has control over it. For example, the private information of a source becomes secret information (intelligence) when control over its dissemination is shared with an intelligence officer, and then becomes public information when the intelligence officer further disseminates it to the public by any number of means, including formal reporting, threat warning, and others. The fourth assumption, intelligence is hoarded, causes conflict points where information transitions from one type to another. The first conflict point, collection, occurs when private transitions to secret information (intelligence). The second conflict point, dissemination, occurs when secret transitions to public information. Thus, conceiving of intelligence using these assumptions demonstrates the cause of collection techniques (to ease the private-secret transition) and dissemination conflicts, and can inform ethical standards of conduct among all agents in the intelligence process.[2][3]

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)