Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| |

OpenStreetMap homepage, showing the world map | |

| Available in | 96 languages and variants,[1] local languages for map data |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Owner | OpenStreetMap Foundation |

| Created by | Steve Coast |

| Products | Editable geographic data, tiled web map layer |

| URL | www |

| Commercial | No |

| Registration | Required for contributors, not required for viewing |

| Users | 10.6 million[2] |

| Launched | 9 August 2004 [3] |

| Current status | Active |

Content license | Open Database License |

| Written in | Ruby, JavaScript |

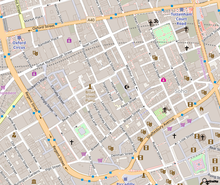

OpenStreetMap (abbreviated OSM) is a website that uses an open geographic database which is updated and maintained by a community of volunteers via open collaboration. Contributors collect data from surveys, trace from aerial photo imagery or satellite imagery, and also import from other freely licensed geodata sources. OpenStreetMap is freely licensed under the Open Database License and as a result commonly used to make electronic maps, inform turn-by-turn navigation, assist in humanitarian aid and data visualisation. OpenStreetMap uses its own topology to store geographical features which can then be exported into other GIS file formats. The OpenStreetMap website itself is an online map, geodata search engine and editor.

OpenStreetMap was created by Steve Coast in response to the Ordnance Survey, the United Kingdom's national mapping agency, failing to release its data to the public under free licences in 2004. Initially, maps were created only via GPS traces, but it was quickly populated by importing public domain geographical data such as the U.S. TIGER and by tracing imagery as permitted by source. OpenStreetMap's adoption was accelerated by Google Maps's introduction of pricing in 2012 and the development of supporting software and applications.

The database is hosted by the OpenStreetMap Foundation, a non-profit organisation registered in England and Wales and is funded mostly[weasel words] via donations.

Steve Coast founded the project in 2004 while at a university in Britain, initially focusing on mapping the United Kingdom.[3] In the UK and elsewhere, government-run and tax-funded projects like the Ordnance Survey created massive datasets but declined to freely and widely distribute them. The first contribution was a street that Coast entered in December 2004 after cycling around Regent's Park in London with a GPS tracking unit.[4][5][6] In April 2006, the OpenStreetMap Foundation was established to encourage the growth, development and distribution of free geospatial data and provide geospatial data for anybody to use and share.

In April 2007, Automotive Navigation Data (AND) donated a complete road data set for the Netherlands and trunk road data for India and China to the project.[7] By July 2007, when the first "The State of the Map" (SotM) conference[8] was held, there were 9,000 registered users. In October 2007, OpenStreetMap completed the import of a US Census TIGER road dataset.[9] In December 2007, Oxford University became the first major organisation to use OpenStreetMap data on their main website.[10] Ways to import and export data have continued to grow – by 2008, the project developed tools to export OpenStreetMap data to power portable GPS units, replacing their existing proprietary and out-of-date maps.[11] In March 2008, two founders of CloudMade, a commercial company that uses OpenStreetMap data, announced that they had received venture capital funding of €2.4 million.[12] In 2010, AOL launched an OSM-based version of MapQuest and committed $1 million to increasing OSM's coverage of local communities for its Patch website.[13]

In 2012, the launch of pricing for Google Maps led several prominent websites to switch from their service to OpenStreetMap and other competitors.[14] Chief among these were Foursquare and Craigslist, which adopted OpenStreetMap, and Apple, which ended a contract with Google and launched a self-built mapping platform using TomTom and OpenStreetMap data.[15]

The OSM project aims to collect data about stationary objects throughout the world, including infrastructure and other aspects of the built environment, points of interest, land use and land cover classifications, and topography. Map features range in scale from international boundaries to hyperlocal details such as shops and street furniture. Although historically significant features and ongoing construction projects are routinely included in the database, the project's scope is generally limited to the present day, as opposed to the past or future.[16]

Each feature comes with structured metadata indicating facts such as names, physical characteristics, contact information, and access restrictions. Standards exist for mapping three-dimensional architectural elements and indoor details within buildings, as well as lane-level navigation details.

OSM's data model differs markedly from that of a conventional GIS or CAD system. It is a topological data structure without the formal concept of a layer, allowing thematically diverse data to commingle and interconnect. A map feature or element is modelled as one of three geometric primitives:[17][18]

OSM manages metadata as a folksonomy. Each element contains key-value pairs, called tags, that identify and describe the feature.[19] A recommended ontology of map features (the meaning of tags) is maintained on a wiki. New tagging schemes can always be proposed by a popular vote of a written proposal in OpenStreetMap wiki, however, there is no requirement to follow this process. There are over 89 million different kinds of tags in use as of June 2017.[20]

The OpenStreetMap data primitives are stored and processed in different formats. OpenStreetMap server uses PostgreSQL database, with one table for each data primitive, with individual objects stored as rows.[21][22]

The data structure is defined as part of the OSM API. The current version of the API, v0.6, was released in 2009. A 2023 study found that this version's changes to the relation data structure had the effect of reducing the total number of relations; however, it simultaneously lowered the barrier to creating new relations and spurred the application of relations to new use cases.[23]

OpenStreetMap data has been favourably compared with proprietary datasources,[24] although as of 2009 data quality varied across the world.[25][26] A study in 2011 compared OSM data with TomTom for Germany. For car navigation TomTom has 9% more information, while for the entire street network, OSM has 27% more information.[27] In 2011, TriMet, which serves the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area, found that OSM's street data, consumed through the routing engine OpenTripPlanner and the search engine Apache Solr, yields better results than analogous GIS datasets managed by local government agencies.[28]

A 2021 study compared the OpenStreetMap Carto style's symbology to that of the Soviet Union's comprehensive military mapping programme, finding that OSM matched the Soviet maps in coverage of some features such as road infrastructure but gave less prominence to the natural environment.[29] According to a 2024 study using PyPSA, OSM has the most detailed and up-to-date publicly available coverage of the European high-voltage electrical grid, comparable to official data from the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity.[30]

All data added to the project needs to have a licence compatible with the Open Data Commons Open Database Licence (ODbL). This can include out-of-copyright information, public domain or other licences. Software used in the production and presentation of OpenStreetMap data may have separate licensing terms.

OpenStreetMap data and derived tiles were originally published under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (CC BY-SA) with the intention of promoting free use and redistribution of the data. In September 2012, the licence was changed to the ODbL in order to define its bearing on data rather than representation more specifically.[31][32] As part of this relicensing process, some of the map data was removed from the public distribution. This included all data contributed by members that did not agree to the new licensing terms, as well as all subsequent edits to those affected objects. It also included any data contributed based on input data that was not compatible with the new terms.

Estimates suggested that over 97% of data would be retained globally, but certain regions would be affected more than others, such as in Australia where 24 to 84% of objects would be retained, depending on the type of object.[33] Ultimately, more than 99% of the data was retained, with Australia and Poland being the countries most severely affected by the change.[34] The license change and resulting deletions prompted a group of dissenting mappers to establish Free Open Street Map (FOSM), a fork of OSM that remained under the previous license.[35]

Map tiles provided by the OpenStreetMap project were licensed under CC-BY-SA-2.0 until 1 August 2020. The ODbL license requires attribution to be attached to maps produced from OpenStreetMap data, but does not require that any particular license be applied to those maps. "©OpenStreetMap Contributors" with link to ODbL copyright page as attribution requirement is used on the site.[36]

OSM publishes official database dumps of the entire "planet" for reuse on minutely and weekly intervals, formatted as XML or binary Protocol Buffers. Alternative third-party distributions provide access to OSM data in other formats or to more manageable subsets of the data. Geofabrik publishes extracts of the database in OSM and shapefile formats for individual countries and political subdivisions. Amazon Web Services publishes the planet on S3 for querying in Athena.[37] As part of the QLever project, the University of Freiburg publishes Turtle dumps suitable for linked data systems.[38] From 2020 to 2024, Meta published the Daylight Map Distribution, which applied quality assurance processes and added some external datasets to OSM data to make it more production-ready.[39] OSM data also forms a major part of the Overture Maps Foundation's dataset and commercial datasets from Mapbox and MapTiler.[40]

Map data is collected by ground survey, personal knowledge, digitizing from imagery, and government data. Ground survey data is collected by volunteers traditionally using tools such as a handheld GPS unit, a notebook, digital camera and voice recorder.

Software applications on smartphones (mobile devices) have made it easy for anybody to survey. The data is then entered into the OpenStreetMap database using a number of software tools including JOSM and Merkaator.[41]

Mapathon competition events are also held by local OpenStreetMap teams and by non-profit organisations and local governments to map a particular area.

The availability of aerial photography and other data from commercial and government sources has added important sources of data for manual editing and automated imports. Special processes are in place to handle automated imports and avoid legal and technical problems.

Ground surveys are performed by a mapper, on foot, bicycle, or in a car, motorcycle, or boat. Map data is typically recorded on a GPS unit or on a smart phone with mapping app; a common file format is GPX.

Once the data has been collected, it is entered into the database by uploading it onto the project's website together with appropriate attribute data. As collecting and uploading data may be separated from editing objects, contribution to the project is possible without using a GPS unit, such as by using paper mapping.

Similar to users contributing data using a GPS unit, corporations (e.g. Amazon) with large vehicle fleets may use telemetry data from the vehicles to contribute data to OpenStreetMap.[42]

Some committed contributors adopt the task of mapping whole towns and cities, or organising mapping parties to gather the support of others to complete a map area.

A large number of less-active users contributes corrections and small additions to the map.[citation needed]

Maxar,[43] Bing,[44] ESRI, and Mapbox are some of the providers of aerial/satellite imagery which are used as a backdrop for map production.

Yahoo! (2006–2011),[45][46] Bing (2010 – till date),[44] and DigitalGlobe (2017[43]–2023[47]) allowed their aerial photography, satellite imagery to be used as a backdrop for map production. For a period from 2009 to 2011, NearMap Pty Ltd made their high-resolution PhotoMaps (of major Australian cities, plus some rural Australian areas) available under a CC BY-SA licence.[48]

Data from several street-level image platforms are available as map data photo overlays. Bing Streetside 360° image tracks, and the open and crowdsourced Mapillary and KartaView platforms provide generally smartphone and dashcam images. Additionally, a Mapillary traffic sign data layer, a product of user-submitted images is also available.[49]

Some government agencies have released official data on appropriate licences. This includes the United States, where works of the federal government are placed under public domain. In the United States, most roads originate from TIGER from the Census Bureau.[50] Geographic names were initially sourced from Geographic Names Information System, and some areas contain water features from the National Hydrography Dataset. In the UK, some Ordnance Survey OpenData is imported. In Canada Natural Resources Canada's CanVec vector data and GeoBase provide landcover and streets.[citation needed]

Globally, OpenStreetMap initially used the prototype global shoreline from NOAA. Due to it being oversimplified and crude, it has been mainly replaced by other government sources or manual tracing.[citation needed]

Out-of-copyright maps can be good sources of information about features that do not change frequently. Copyright periods vary, but in the UK Crown copyright expires after 50 years and hence old Ordnance Survey maps can legally be used. A complete set of UK 1 inch/mile maps from the late 1940s and early 1950s has been collected, scanned, and is available online as a resource for contributors.[51]

The map data can be edited from a number of editing applications that provide aids including satellite and aerial imagery, street-level imagery, GPS traces, and photo and voice annotations.

By default, the official OSM website directs contributors to the Web-based iD editor.[52][53] Meta develops a fork of this editor, Rapid, that provides access to external datasets, including some derived from machine learning detections.[54] For complex or large-scale changes, experienced users often turn to more powerful desktop editing applications such as JOSM and Potlatch.

Several mobile applications also edit OSM. Go Map!! and Vespucci are the primary full-featured editors for iOS and Android, respectively. StreetComplete is an Android application designed for laypeople around a guided question-and-answer format. Every Door, Maps.me, Organic Maps, and OsmAnd include basic functionality for editing points of interest.

Between 2018 and 2023, the top five editing tools by number of edits were JOSM, iD, StreetComplete, Rapid, and Potlatch.[55]

OSM accepts contributions from the general public. Changesets submitted through editors and the OSM API immediately enter the database and are quickly published for reuse, without going through peer review beforehand. The API only validates changes for basic well-formedness, but not for topological or logical consistency or for adherence to community norms.

As a crowdsourced project, OSM is susceptible to several forms of data vandalism, including copyright infringement, graffiti, and spam.[56] Overall, vandalism accounts for an estimated 0.2% of edits to OSM, which is relatively low compared to vandalism on Wikipedia. Members of the community detect and fix most unintentional errors and vandalism promptly,[57] by monitoring the slippy map and revision history on the main website, as well as by searching for issues using tools like OSMCha, OSM Inspector, and Osmose. In addition to community vigilance, the OpenStreetMap Foundation's Data Working Group and a group of administrators are responsible for responding to vandals.[56] As of 2022, a comprehensive security assessment of the OSM data model has yet to take place.[58]

There have been several high-profile incidents of vandalism and other errors in OSM:

Players of Pokémon Go have been known to vandalize OSM, one of the game's map data sources, to manipulate gameplay. However, this vandalism is casual, rarely sustained, and it is predictable based on the mechanics of the game.[57]

The project has a geographically diverse user-base, due to emphasis of local knowledge and "on-the-ground" situation in the process of data collection.[65] Many early contributors were cyclists who survey with and for bicyclists, charting cycleroutes and navigable trails.[66] Others are GIS professionals. Contributors are predominately men, with only 3–5% being women.[67]

By August 2008, shortly after the second The State of the Map conference was held, there were over 50,000 registered contributors; by March 2009, there were 100,000 and by the end of 2009 the figure was nearly 200,000. In April 2012, OpenStreetMap cleared 600,000 registered contributors.[68] On 6 January 2013, OpenStreetMap reached one million registered users.[69] Around 30% of users have contributed at least one point to the OpenStreetMap database.[70][71]

As per a study conducted in 2011, only 38% of members carried out at least one edit and only 5% of members created more than 1000 nodes. Most members are in Europe (72%).[72] According to another study, when a competing maps platform is launched, OSM attracts fewer new contributors and pre-existing contributors increase their level of contribution possibly driven by their ideological attachment to the platform. Overall, there is a negative effect on the quantum of contributions.[73]

Some companies freely license satellite/aerial/street imagery sources from which OpenStreetMap contributors trace roads and features, while other companies make data available for importing map data. Automotive Navigation Data (AND) provided a complete road data set for Netherlands and trunk roads data for China and India. Amazon Logistics uses OpenStreetMap for navigation and has a team which revises the map based on GPS traces and feedback from its drivers.[74] In eight Southeast Asian countries, Grab has contributed more than 800,000 kilometres (500,000 mi) of roads based on drivers' GPS traces, including many narrow alleyways that are missing from other mapping platforms.[75] eCourier also contributes its drivers' GPS traces to OSM.

According to a study, about 17% of road kilometers were last touched by corporate teams in March 2020.[76] The top 13 corporate contributors during 2014–2020 include Apple, Kaart, Amazon, Facebook, Mapbox, Digital Egypt, Grab, Microsoft, Telenav, Developmentseed, Uber, Lightcyphers and Lyft.[74]

According to OpenStreetMap Statistics, the over all percentage of edits from corporations peaked at about 10% in 2020 and 2021 and has since fallen to about 2-3% in 2024.[77]

Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) is a nonprofit organisation promoting community mapping across the world. It developed the open source HOT Tasking Manager for collaboration, and contributed to mapping efforts after the April 2015 Nepal earthquake, the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes, and the 2016 Ecuador earthquake. The Missing Maps Project, founded by the American Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders, and other NGOs, uses HOT Tasking Manager. The University of Heidelberg hosts the Disastermappers Project for training university students in mapping for humanitarian purposes. When Ebola broke out in 2014, the volunteers mapped 100,000 buildings and hundreds of miles of roads in Guinea in just five days.[78] Local groups such as Ramani Huria in Dar es Salaam incorporate OSM mapping into their community resilience programmes.

Since 2007, the OpenStreetMap community has organised State of the Map (SotM), an annual international conference at which stakeholders present on technical progress and discuss policy issues.[8][80] The conference is held each year in a different city around the world. Various regional editions of State of the Map are also held for each continent, regions such as the Baltics and Latin America, and some countries with especially active local communities, such as France, Germany, and the United States.

The official OSM website at openstreetmap.org is the project's main hub for contributors. A reference implementation of a slippy map (featuring a selection of third-party tile layers), a revision log, and integrations with basic geocoders and route planners facilitate the community's management of the database contents. Logged-in users can access an embedded copy of the iD editor and shortcuts for desktop editors for contributing to the database, as well as some rudimentary social networking features such as user profiles and diaries. The website's built-in REST API and OAuth authentication enable third-party applications to programmatically interact with the site's major functionality, including submitting changes. Much of the website runs as a Ruby on Rails application backed by a PostgreSQL database.

Strictly speaking, the OSM project produces only a geographic database, leaving data consumers to handle every aspect of postprocessing the data and presenting it to end users. However, a large ecosystem of command line tools, software libraries, and cloud services has developed around OSM, much of it as free and open-source software.

Two kinds of software stacks have emerged for rendering OSM data as an interactive slippy map. In one, a server-side rendering engine such as Mapnik prerenders the data as a series of raster image tiles, then serves them using a library such as mod_tile. A library such as OpenLayers or Leaflet displays these tiles on the client side on the slippy map. Alternatively, a server application converts raw OSM data into vector tiles according to a schema, such as Mapbox Streets, OpenMapTiles, or Shortbread. These tiles are rendered on the client side by a library such as the Mapbox Maps SDK, MapLibre, Mapzen's Tangrams, or OpenLayers. Applications such as Mapbox Studio allow designers to author vector styles in an interactive, visual environment.[81] Vector maps are especially common among three-dimensional mapping applications and mobile applications.

A geocoder indexes map data so that users can search it by name and address (geocoding) or look up an address based on a given coordinate pair (reverse geocoding). Several geocoders are designed to index OSM data, including Nominatim (from the Latin, 'by name'), which is built into the official OSM website along with GeoNames.[82][83] Komoot's Photon search engine provides incremental search functionality based on a Nominatim database. Element 84's natural language geocoder uses a large language model to identify OSM geometries to return.[84]

A variety of route planning libraries and services are based on OSM data. OSM's official website has featured GraphHopper, the Open Source Routing Machine, and Valhalla since February 2015.[85][86] Other widely deployed routing engines include Openrouteservice and OpenTripPlanner, which specializes in public transport routing.

OSM is an important source of geographic data in many fields, including transportation, analysis, public services, and humanitarian aid. However, much of its use by consumers is indirect via third-party products, because customer reviews and aerial and satellite imagery are not part of the project per se.[40]

A variety of applications and services allow users to visualise OSM data in the form of a map. The official OSM website features an interactive slippy map interface so that users can efficiently edit maps and view changesets. It presents the general-purpose OpenStreetMap Carto style alongside a selection of specialised styles for cycling and public transport. Beyond this reference implementation, community-maintained map applications focus on alternative cartographic representations and specialised use cases. For example, OpenRailwayMap is a detailed online map of the world's railway infrastructure based on OSM data.[87] OpenSeaMap is a world nautical chart built as a mashup of OpenStreetMap, crowdsourced water depth tracks, and third-party weather and bathymetric data. OpenTopoMap uses OSM and SRTM data to create topographic maps.[88] In March 2010, Steve Coast posted about the release of the very first WordPress plugin for displaying slippy OpenStreetMap maps on the OpenStreetMap Blog,[89] which uses OpenLayers for map rendering. On the desktop, applications such as GNOME Maps and Marble provide their own interactive styles, and GIS suites such as QGIS allow users to produce their own custom maps based on the same data.

{{Maplink}}) example, highlighting the Eiffel Tower using live OpenStreetMap dataMany commercial and noncommercial websites feature maps powered by OSM data in locator maps, store locators, infographics, story maps, and other mashups. Locator maps on Wikipedia and Wikivoyage articles for cities and points of interest are powered by a MediaWiki extension and the OSM-based Wikimedia Maps service.[90] The locator maps on Craigslist,[91] Facebook,[92] Flickr,[93] Foursquare City Guide,[94] Gurtam's Wialon,[95] and Snapchat[96] are also powered by OSM. From 2013 to 2022, GitHub visualized any uploaded GeoJSON data atop an OSM-based Mapbox basemap.[97][98]

In 2012, Apple quietly switched the locator map in iPhoto from Google Maps to OSM.[99] Interactive OSM-based maps appear in many mobile navigation applications, fitness applications, and augmented reality games, such as Strava.[100]

The Overpass API searches the OSM database for features whose metadata or topology match criteria specified in a structured query language.[101] Overpass turbo is an integrated development environment for querying this API. Bellingcat develops an alternative Overpass frontend for geolocating photographs.[102]

QLever and Sophox are triplestores that accept standard SPARQL queries to return facts about the OSM database. Geographic information retrieval systems such as NLMaps Web[103] and OSCAR[104] answer natural language queries based on OSM data. OSMnx is a Python package for analysing and visualising the OSM road network.[105]

OSM is often a source for realistic, large-scale transport network analyses[106] because the raw road network data is freely available or because of aspects of coverage that are uncommon in proprietary alternatives. OSM data can be imported into professional-grade traffic simulation frameworks such as Aimsun Next,[107] Eclipse SUMO,[108] and MATSim,[109] as well as urban planning–focused simulators such as A/B Street.[110] A team at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute has used Valhalla's map matching function to evaluate advanced driver-assistance systems.[111] The United States Census Bureau has analysed routes generated by the Open Source Routing Machine along with American Community Survey data to develop a socioeconomic profile of commuters affected by the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse.[112]

OSM is also used in conservation and land-use planning research. The annual Forest Landscape Integrity Index is based on a comprehensive map of remaining roadless areas derived from OSM's road network.[113][114] OpenSentinelMap is a global land use dataset based on OSM's land use areas and Sentinel-2 imagery, designed for feature detection and image segmentation using computer vision.[115]

Various groups, including researchers, data journalists, the Open Knowledge Foundation, and Geochicas, have used OSM in conjunction with Wikidata to explore the demographics of people honoured by street names and raise awareness of gender bias in naming decisions.[116][117][118]

OSM is a data source for some Web-based map services. In 2010, Bing Maps introduced an option to display an OSM-based map[119] and later began including building data from OSM by default.[62] Wheelmap.org is a portal for discovering wheelchair-accessible places, mashing up OSM data with a separate, crowdsourced customer review database.

Mobile applications such as CycleStreets, Karta GPS, Komoot,[120] Locus Map, Maps.me, Organic Maps, and OsmAnd also provide offline route planning capabilities. Apple Maps uses OSM data in many countries.[121] Some of Garmin's GPS products incorporate OSM data.[122] OSM is a popular source for road data among Iranian navigation applications, such as Balad.[63] Geotab[123] and TeleNav[124] also use OSM data in their in-car navigation systems.

Some public transportation providers rely on OpenStreetMap data in their route planning services and for other analysis needs.

OSM data appears in the driver or rider application or powers backend operations for ridesharing companies and related services.[125] In 2022, Grab completed a migration from Google Maps and Here Maps to an in-house, OSM-based navigation solution, reducing trip times by about 90 seconds.[75] In 2024, Ola introduced a mapping platform partly based on OSM data.[126]

In 2019, owners of Tesla cars found that the Smart Summon automatic valet parking feature within Tesla Autopilot relied on OSM's coverage of parking lot details.[127] Webots uses OSM data to simulate realistic surroundings for autonomous vehicles.[128]

Humanitarian aid agencies use OSM data both proactively and reactively. OSM's road and building coverage allow them to discover patterns of disease outbreaks and target interventions such as antimalarial medications toward remote villages. After a disaster occurs, they produce large-format printed maps and downloadable maps for GPS tracking units for aid workers to use in the field.[130]

The 2010 Haiti earthquake established a model for non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to collaborate with international organisations. OpenStreetMap and Crisis Commons volunteers used available satellite imagery to map the roads, buildings and refugee camps of Port-au-Prince in just two days, building "the most complete digital map of Haiti's roads".[131][132] The resulting data and maps have been used by several organisations providing relief aid, such as the World Bank, the European Commission Joint Research Centre, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, UNOSAT and others.[133]

After Haiti, the OpenStreetMap community continued mapping to support humanitarian organisations for various crises and disasters. After the Northern Mali conflict (January 2013), Typhoon Haiyan[134][135] in the Philippines (November 2013), and the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa (March 2014), the OpenStreetMap community in association with the NGO Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) has shown it can play a significant role in supporting humanitarian organisations.[78]

OSM is a map data source for many location-based games that require broad coverage of local details such as streets and buildings. One of the earliest such games was Hasbro's short-lived Monopoly City Streets (2009), which offered a choice between OSM and Google Maps as the playing board.[136][137] Battlefield 4 (2013) used a customized OSM-based Mapbox map in its leaderboards.[138] In 2013, Ballardia shut down testing of World of the Living Dead: Resurrection, because too many players attempted to use the Google Maps–based game, then relaunched it after switching to OSM, which could handle thousands of players.[139]

Flight simulators combine OSM's coverage of roads and structures with other sources of natural environment data, acting as sophisticated 3D map renderers, in order to add realism to the ground below. X-Plane 10 (2011) replaced TIGER and VMAP0 with OSM for roads, railways, and some bodies of water.[140][141] Microsoft Flight Simulator (2020) introduced software-generated building models based in part on OSM data.[62] In 2020, FlightGear Flight Simulator officially integrated OSM buildings and roads into the official scenery.[142]

City-building games use a subset of OSM data as a base layer to take advantage of the player's familiarity with their surroundings. In NIMBY Rails (2021), the player develops a railway network that coexists with real-world roads and bodies of water.[143] In Jutsu Games' Infection Free Zone (2024), the player builds fortifications amid a post-apocalyptic world based on OSM streets and buildings.[144]

Alternate reality games rely on OSM data to determine where rewards and other elements of the game spawn in the player's presence, such as the 'portals' in Ingress, the 'PokéStops' and 'Pokémon Gyms' in Pokémon Go, and the 'tappables' in Minecraft Earth (2019).[145] In 2017, when Niantic migrated its augmented reality titles, including Ingress and Pokémon Go, from Google Maps to OSM, the overworld maps in these games initially became more detailed for some players but completely blank for others, due to OSM's uneven geographic coverage at the time.[146][147] In the first six weeks after launching in South Korea, Pokémon Go produced a seventeenfold spike in daily OSM contributions within the country.[148] In 2024, Niantic migrated its titles to Overture Maps data, which incorporates some OSM data.[149]

OSM and projects based on it have been recognized for their contributions to design and the public good:

According to the Open Data Institute, OSM is one of the most successful collaboratively maintained open datasets in existence.[156] A 2020 research report by Accenture estimated the total replacement value of the OSM database, the value of OSM software development effort, and maintenance overhead at $1.67 billion,[157] roughly equivalent to the value of the Linux kernel in 2008.[158] Several startups have turned OSM-based software as a service into a business model, including Carto, Mapbox,[159] MapTiler, and Mapzen. The Overture Maps Foundation incorporates OSM data in some of its GIS layers.[160]

Several open collaborative mapping projects are modeled after OSM and rely on OSM software. OpenHistoricalMap is a world historical map that tracks the evolution of human geography over time, from prehistory to the present day. OpenGeofiction focuses on fantasy cartography and worldbuilding. The OSM community sees these projects as complements for aspects of geography that are out of scope for OSM.[161][162][16]

Leaderboards allow players to compete within their geographic regions. The maps are tailored to the look and feel of the game.

Foody, Giles; et al. (2017). Mapping and the Citizen Sensor. London: Ubiquity Press. ISBN 978-1-911529-16-3. JSTOR j.ctv3t5qzc.