Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| History of Cornwall |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Cornwall goes back to the Paleolithic, but in this period Cornwall only had sporadic visits by groups of humans. Continuous occupation started around 10,000 years ago after the end of the last ice age. When recorded history started in the first century BCE, the spoken language was Common Brittonic, and that would develop into Southwestern Brittonic and then the Cornish language. Cornwall was part of the territory of the tribe of the Dumnonii that included modern-day Devon and parts of Somerset. After a period of Roman rule, Cornwall reverted to rule by independent Romano-British leaders and continued to have a close relationship with Brittany and Wales as well as southern Ireland, which neighboured across the Celtic Sea. After the collapse of Dumnonia, the remaining territory of Cornwall came into conflict with neighbouring Wessex.

By the middle of the ninth century, Cornwall had fallen under the control of Wessex, but it kept its own culture. In 1337, the title Duke of Cornwall was created by the English monarchy, to be held by the king's eldest son and heir. Cornwall, along with the neighbouring county of Devon, maintained Stannary institutions that granted some local control over its most important product, tin, but by the time of Henry VIII most vestiges of Cornish autonomy had been removed as England became an increasingly centralised state under the Tudor dynasty. Conflicts with the centre took place with the Cornish Rebellion of 1497 and Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549.

By the end of the 18th century, Cornwall was administered as an integral part of the Kingdom of Great Britain along with the rest of England and the Cornish language had gone into steep decline. The Industrial Revolution brought huge change to Cornwall, as well as the adoption of Methodism among the general populace, turning the area nonconformist. Decline of mining in Cornwall resulted in mass emigration overseas and the Cornish diaspora, as well as the start of the Celtic Revival and Cornish revival which resulted in the beginnings of Cornish nationalism in the late 20th century.

Cornwall's Early Medieval history, in particular the early Welsh and Breton references to a Cornish King named Arthur, have featured in such legendary works as Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, predating the Arthurian legends of the Matter of Britain (see the list of legendary rulers of Cornwall).

Cornwall was only sporadically occupied during the Palaeolithic, but people returned around 10,000 years ago in the Mesolithic, after the end of the last ice age. There is substantial evidence of occupation by hunter gatherers in this period.[1]

The upland areas of Cornwall were the parts first open to settlement as the vegetation required little in the way of clearance: they were perhaps first occupied in Neolithic times (Palaeolithic remains are almost non-existent in Cornwall). Many megaliths of this period exist in Cornwall and prehistoric remains in general are more numerous in Cornwall than in any English county except Wiltshire. The remains are of various kinds and include menhirs, barrows and hut circles.[2][3]

Cornwall and neighbouring Devon had large reserves of tin, which was mined extensively during the Bronze Age by people associated with the Beaker culture. Tin is necessary to make bronze from copper, and by about 1600 BCE the West Country was experiencing a trade boom driven by the export of tin across Europe. [citation needed] This prosperity helped feed the skilfully wrought gold ornaments recovered from Wessex culture sites. Ingots of tin, some recovered from shipwrecks dated to the 12th century BCE off the coast of modern Israel, were analysed isotopically and found to have originated in Cornwall.[4]

There is evidence of a relatively large-scale disruption of cultural practices around the 12th century BCE that some scholars think may indicate an invasion or migration into southern Britain.[citation needed]

Around 750 BCE the Iron Age reached Britain, permitting greater scope of agriculture through the use of new iron ploughs and axes. The building of hill forts also peaked during the British Iron Age. During broadly the same time (900 to 500 BCE), Celtic cultures and peoples spread across the British Isles.

During the British Iron Age Cornwall, like all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, was inhabited by Celts known as the Britons. The Celtic language spoken at the time, Common Brittonic, eventually developed into several distinct tongues, including Cornish.[5]

The first account of Cornwall comes from the Sicilian Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (c. 90 BCE – c. 30 BCE), supposedly quoting or paraphrasing the 4th-century BCE geographer Pytheas, who had sailed to Britain:

The inhabitants of that part of Britain called Belerion (or Land's End) from their intercourse with foreign merchants, are civilised in their manner of life. They prepare the tin, working very carefully the earth in which it is produced ... Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhône.[6]

Claims have been made that the Phoenicians traded directly with Cornwall for tin. There is no archaeological evidence for this and modern historians have debunked earlier antiquarian constructions of "the Phoenician legacy of Cornwall",[7][8][9][10] including belief that the Phoenicians even settled Cornwall.

By the time that Classical written sources appear, Cornwall was inhabited by tribes speaking Celtic languages. The ancient Greeks and Romans used the name Belerion or Bolerium for the south-west tip of the island of Britain, but the late-Roman source for the Ravenna Cosmography (compiled about 700 CE) introduces a place-name Puro coronavis, the first part of which seems to be a misspelling of Duro (meaning Fort). This appears to indicate that the tribe of the Cornovii, known from earlier Roman sources as inhabitants of an area centred on modern Shropshire, had by about the 5th century established a power-base in the south-west (perhaps at Tintagel).[11]

The tribal name is therefore likely to be the origin of Kernow or later Curnow used for Cornwall in the Cornish language. John Morris suggested that a contingent of the Shropshire Cornovii was sent to South West Britain at the end of the Roman era, to rule the land there and keep out the invading Irish, but this theory was dismissed by Professor Philip Payton in his book Cornwall: A History.[5] Given the geographical separation between the three tribes known as Cornovii–the third being found in modern-day Caithness– and the absence of any known connection, the Cornish Cornovii are generally assumed to compose a completely separate tribe. While their name may derive from their inhabitation of a peninsula, the absence of a peninsula in the other two cases has led to the postulation of a derivation from these tribes' worship of a "horned god."[12]

The English name, Cornwall, comes from the Celtic name, to which the Old English word Wealas "foreigner" is added.[13]

In pre-Roman times, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of Dumnonia, and was later known to the Anglo-Saxons as "West Wales", to distinguish it from "North Wales" (modern-day Wales).[14]

During the time of Roman dominance in Britain, Cornwall was rather remote from the main centres of Romanisation. The Roman road system extended into Cornwall, but the only known significant Roman sites are three forts:- Tregear near Nanstallon was discovered in early 1970s, the other two found more recently at Restormel Castle, Lostwithiel (discovered 2007) and a fort near to St Andrew's Church in Calstock (discovered early in 2007).[15] A Roman style villa was found at Magor Farm near Camborne.[16]

Pottery and other evidence suggesting the presence of an ironworks have been found at the undisclosed location near St Austell, Cornwall. Experts say the discovery challenges the belief that Romans did not settle in the county and stopped in east Devon where Isca Dumnoniorum became a flourishing provincial capital of the Dumnonii.[17] Prof. Barry Cunliffe notes that "in the south-west peninsula of Devon and Cornwall the lack of Romanization, after a brief military occupation in the first century, is particularly striking. West of Exeter the native socio-economic system simply continued unhindered".[18]

Only a few Roman milestones have been found in Cornwall; two have been recovered from around Tintagel in the north, one at Mynheer Farm[19] near the hill fort at Carn Brea, Redruth, another two close to St Michael's Mount, one of which is preserved at Breage Parish Church, and one in St Hilary's Church, St Hilary (Cornwall).[20] The stone at Tintagel Parish Church bears an inscription to Imperator Caesar Licinius, and the other stone at Trethevy is inscribed to the Imperial Caesars Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus.[21] According to Léon Fleuriot, however, Cornwall remained closely integrated with neighbouring territories by well-travelled sea routes. Fleuriot suggests that an overland route connecting Padstow with Fowey and Lostwithiel served, in Roman times, as a convenient conduit for trade between Gaul (especially Armorica) and the western parts of the British Isles.[22]

Archaeological sites at Chysauster Ancient Village and Carn Euny in West Penwith and the Isles of Scilly demonstrate a uniquely Cornish 'courtyard house' architecture built in stone of the Roman period, entirely distinct from that of southern Britain, yet with parallels in Atlantic Ireland, North Britain and the Continent, and influential on the later development of stone-built fortified homesteads known in Cornwall as "Rounds".[23]

In the wake of the Roman withdrawal from Great Britain in about 410, Saxons and other Germanic peoples were able to conquer and settle most of the east of the island over the next two centuries. In the west, Devon and Cornwall held out as the British kingdom of Dumnonia.

Dumnonia had close cultural contacts with Christian Ireland, Wales, Romano-Celtic Brittany and Byzantium via the West Atlantic trade network, and there is exceptional archaeological evidence for Late Antique trading contacts at the stronghold of Tintagel in Cornwall.[24] The Breton language is closer to Cornish than to Welsh, showing the close contacts between the areas.[25]

The early kings of Wessex are notable for the possible prevalence of Brythonic names among them[26] and therefore care should be exercised in assuming a stark ethnic antipathy between emergent 'British' and 'English' identities, peoples and culture; rather a struggle for dominance of warring elites more or less aligned with eastern 'Germanic' and western 'Romano-Celtic' cultures and peoples.[26] Atlantic Brythons were often recorded in alliance with Scandinavian forces such as the Danes, or Normans in Brittany, up to the period of the Norman Conquest.[27]

In the early eighth century, Cornwall was probably a sub-division of Dumnonia, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 710, Geraint, king of Dumnonia, fought against Ine, king of Wessex. The Annales Cambriae states that in 722, the Battle of Hehil "among the Cornishmen" was won by the Britons. In the view of the historian Thomas Charles-Edwards, this probably indicates that Dumnonia had fallen by 722, and that the British victory of that year against Wessex secured the survival of the new kingdom of Cornwall for another one hundred and fifty years. There were intermittent battles between Wessex and Cornwall for the rest of the eighth century, and Cuthred, king of Wessex, fought against the Cornish in 743 and 753.[28]

However, according to John Reuben Davies, Dumnonia ceased to exist around the beginning of the ninth century, but:

In 814, King Egbert of Wessex ravaged Cornwall "from the east to the west", and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 825 the Cornish fought the men of Devon. In 838 the Cornish in alliance with Vikings were defeated by the West Saxons at the Battle of Hingston Down.[30] This was the last recorded battle between Cornwall and Wessex, and possibly resulted in the loss of Cornish independence.[31] In 875, the Annales Cambriae record that king Dungarth of Cornwall drowned, yet Alfred the Great had been able to go hunting in Cornwall a decade earlier suggesting Dungarth was likely an under-king. Kenstec (c.833-c.870) became the first bishop of Cornwall to profess obedience to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and in the same period the bishop of Sherborne was instructed to visit Cornwall annually to "root out the errors of the Cornish Church", further indications that Cornwall was becoming subject to Wessex in the middle of the ninth century.[32][33] In the 880s Alfred the Great was able to leave estates in Cornwall in his will.[34]

William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120, says that in about 927, King Æthelstan of England expelled the Cornish from Exeter and fixed Cornwall's eastern boundary at the River Tamar. T. M. Charles-Edwards dismisses William's account as an "improbable story" on the ground that Cornwall was by then firmly under English control.[35] John Reuben Davies sees the expedition as the suppression of a British uprising, which was followed by the confinement of the Cornish beyond the Tamar and the creation of a separate bishopric for Cornwall.[36] Although English kings granted land in the eastern part in the ninth century, no grants are recorded in the western half until the mid-tenth century.[31]

Cornwall now acquired Anglo-Saxon administrative features such as the hundred system. Unlike Devon, Cornwall's culture was not anglicised. Most people still spoke Cornish, and place-names are still mainly Brittonic.[35][36] In 944 Æthelstan's successor, Edmund I, styled himself 'King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons'.[37]

The antiquarian William Camden wrote in his book Britannia in 1607:

The first centuries after the Romans left are known as the Age of the Saints in Celtic Christianity, and a revival of Celtic art spread from Ireland, Wales and Scotland into Great Britain, Brittany, and beyond. According to tradition the area was evangelised in the 5th and 6th centuries by the children of Brychan Brycheiniog and saints from Ireland. Cornish saints such as Piran, Meriasek, or Geraint exercised a religious and arguably political influence; they were often closely connected to the local civil rulers and in some cases were kings themselves.[39] There was an important monastery at Bodmin and sporadically, Cornish bishops are named in various records.

By the 880s more Saxon priests were being appointed to the Church in Cornwall and they controlled some church estates like Polltun, Caellwic and Landwithan (Pawton, in St Breock or Pillaton in east Cornwall); perhaps Celliwig (Kellywick in Egloshayle or possibly Callington (formally Kellywick)); and Lawhitton. Eventually they passed these over to Wessex kings. However, according to Alfred the Great's will the amount of land he owned in Cornwall was very small.[34] West of the Tamar Alfred the Great only owned a small area in the Stratton region, plus a few other small estates around Lifton on Cornish soil east of the Tamar). These were provided to him through the Church whose Canterbury appointed priesthood was increasingly English dominated.[citation needed]

The early organisation and affiliations of the Church in Cornwall are unclear, but in the mid-9th century it was led by a Bishop Kenstec with his see at Dinurrin, a location which has sometimes been identified as Bodmin and sometimes as Gerrans. Kenstec acknowledged the authority of Ceolnoth, bringing Cornwall under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the 920s or 930s King Athelstan established a bishopric at St Germans to cover the whole of Cornwall, which seems to have been initially subordinated to the see of Sherborne but emerged as a full bishopric in its own right by the end of the 10th century. The first few bishops here were native Cornish, but those appointed from 963 onwards were all English. From around 1027, the see was held jointly with that of Crediton, and in 1050, they were merged to become the diocese of Exeter.[37]

In 1013 Wessex was conquered by a Danish army under the leadership of the Viking leader and King of Denmark Sweyn Forkbeard. Sweyn annexed Wessex to his Viking empire which included Denmark and Norway. He did not, however, annex Cornwall, Wales and Scotland, allowing these "client nations" self-rule in return for an annual payment of tribute or "danegeld". Between 1013 and 1035 Cornwall, Wales, much of Scotland and Ireland were not included in the territories of King Canute the Great.[41]

The chronology of English expansion into Cornwall is unclear, but it had been absorbed into England by the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–1066), when it apparently formed part of Godwin's and later Harold's earldom of Wessex.[42] The records of Domesday Book show that by this time the native Cornish landowning class had been almost completely dispossessed and replaced by English landowners, the largest of whom was Harold Godwinson himself.[43]

The Cornish language continued to be spoken, particularly in west and mid Cornwall, and evolved a number of characteristics that began to separate it from its descendant language of Breton. The latter also went through evolution over the centuries, however they remain exceedingly similar. As well, Cornwall showed a very different type of settlement pattern from that of Saxon Wessex and places continued, even after 1066, to be named in the Celtic Cornish tradition.[44] Mills argues that the Breton rulers of Cornwall, as allies of the Normans, brought about an 'Armorican Return'[44] with Cornu-Breton retaining its status as a prestige language.

Legend has it that Condor, a survivor of the Cornish royal line, was kept as the first Earl of Cornwall by William the Conqueror following the Norman conquest of England.[45] In 1068 Brian of Brittany, son of Eudes, Count of Penthièvre, was created Earl of Cornwall, and naming evidence cited by medievalist Edith Ditmas suggests that many other post-Conquest landowners in Cornwall were Breton allies of the Normans, the Bretons being descended from Britons who had fled to what is today France during the early years of the Anglo-Saxon conquest.[46] and further proposed this period for the early composition of the Tristan and Iseult cycle by poets such as Béroul from a pre-existing shared Brittonic oral tradition.[47] Earl Brian defeated a second raid in the southwest of England, launched from Ireland by Harold's sons in 1069.[48] Brian was granted lands in Cornwall but by 1072 he had probably returned to Brittany: he died without issue[citation needed].

Much of the land in Cornwall was seized and transferred into the hands of a new Norman aristocracy, with the lion's share going to Robert, Count of Mortain, half-brother of King William and the largest landholder in England after the king. Some land was held by King William and by existing monasteries – the remainder by the Bishop of Exeter, and a single manor each by Judhael of Totnes and Gotshelm[49] (brother of Walter de Claville).

Robert became Earl in succession to Brian; nothing is known of Cadoc apart from what William Worcester says four centuries later. Four Norman castles were built in east Cornwall at different periods, at Launceston, Trematon, Restormel and Tintagel. A new town grew up around Launceston castle[50] and this became the capital of the county. On several occasions over the following centuries noblemen were created Earl of Cornwall, but each time their line soon died out and the title lapsed until revived for a new appointee. In 1336, Edward, the Black Prince was named Duke of Cornwall, a title that has been awarded to the eldest son of the Sovereign since 1421.[citation needed]

A popular Cornish literature, centred on the religious-themed mystery plays, emerged in the 14th century (see Cornish literature) based around Glasney College—the college established by the Bishop of Exeter in the 13th century.[51]

It has been claimed as one of the great ironies of history that three Cornish-speaking Cornishmen brought the English language back from the verge of extinction – John of Cornwall, John Trevisa and Richard Pencrych.[52]

John of Trevisa was a Cornish cleric instrumental in translation of the Bible into English under John Wycliffe's proto-Reformation and, ironically for a Cornish-speaker, is the third most cited source for the very first appearance of many words in the English language. He also added many notes to his translation c. 1387 of the Polychronicon relating to the geography and culture of Cornwall.

Norman absentee landlords became replaced by a new Cornish-Norman ruling class including scholars such as Richard Rufus of Cornwall. These families eventually became the new rulers of Cornwall, typically speaking Norman French, Breton-Cornish, Latin, and eventually English, with many becoming involved in the operation of the Stannary Parliament system, the Earldom and eventually the Duchy of Cornwall.[53] The Cornish language continued to be spoken.

The general tendency of administrative centralisation under the Tudor dynasty began to undermine Cornwall's distinctive status. For example, under the Tudors, the practice of distinguishing between some laws, such as those related to the tin industry, that applied simply in Anglia or in Anglia et Cornubia (in England and Cornwall) ceased.[54]

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 originated among Cornish tin miners who opposed the raising of taxes by Henry VII to make war on Scotland. This levy was resented for the economic hardship it would cause; it also intruded on a special Cornish tax exemption. The rebels marched on London, gaining supporters as they went, but were defeated at the Battle of Deptford Bridge.

The Cornish also rose up in the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549. Much of south-western Britain rebelled against the Act of Uniformity 1549, which introduced the obligatory use of the Protestant Book of Common Prayer. Cornwall was mostly Catholic in sympathy at this time; the Act was doubly resented in Cornwall because the Prayer Book was in English only and most Cornish people at this time spoke the Cornish language rather than English. They therefore wished church services to continue to be conducted in Latin; although they did not understand this language either, it had the benefit of long-established tradition and lacked the political and cultural connotations of the use of English. Twenty percent of the Cornish population are believed to have been killed during 1549: it is one of the major factors that contributed to the decline in the Cornish language.[55]

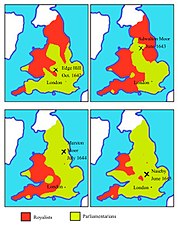

Cornwall played a significant role during the English Civil War, as it was a Royalist semi-enclave in the generally Parliamentarian south-west. The reason for this was that Cornwall's rights and privileges were tied up with the royal Duchy and Stannaries and so the Cornish saw the King as protector of their rights and Ducal privileges. The strong local Cornish identity also meant the Cornish would resist any meddling in their affairs by any outsiders. The English Parliament wanted to reduce royal power. Parliamentary forces invaded Cornwall three times and burned the Duchy archives. In 1645 Cornish Royalist leader Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet made Launceston his base and he stationed Cornish troops along the River Tamar and issued them with instructions to keep "all foreign troops out of Cornwall". Grenville tried to use "Cornish particularist sentiment" to muster support for the Royalist cause and put a plan to the Prince which would, if implemented, have created a semi-independent Cornwall.[56][57][58][59]

On 1 November 1755 at 09:40 the Lisbon earthquake caused a tsunami to strike the Cornish coast at around 14:00. The epicentre was approximately 250 miles (400 km) off Cape St Vincent on the Portuguese coast, over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south west of the Lizard. At St Michael's Mount, the sea rose suddenly and then retired, ten minutes later it rose 6 ft (1.8 m) very rapidly, then ebbed equally rapidly, and continued to rise and fall for five hours. The sea rose 8 ft (2.4 m) in Penzance and 10 ft (3.0 m) at Newlyn. The same effect was reported at St Ives and Hayle. The 18th-century French writer, Arnold Boscowitz, claimed that "great loss of life and property occurred upon the coasts of Cornwall".[60]

At one time the Cornish were the world's foremost experts of mining (See Mining in Cornwall and Devon ) and a School of Mines was established in 1888. As Cornwall's reserves of tin began to be exhausted, many Cornishmen emigrated to places such as the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa where their skills were in demand.

There is only one mine South Crofty in Cornwall, that is currently being restarted. Also, a popular legend says that wherever you may go in the world, if you see a hole in the ground, you'll find a Cornishman at the bottom of it.[61] Several Cornish mining words are in use in English language mining terminology, such as costean, gunnies, and vug.

Since the decline of tin mining, agriculture and fishing, the area's economy has become increasingly dependent on tourism—some of Britain's most spectacular coastal scenery can be found here. However, Cornwall is one of the poorest parts of Western Europe and it has been granted Objective 1 status by the EU.

In 2019, Canadian mining company, Strongbow Exploration announced it was looking to resume tin mining at South Crofty.[62]

Cornwall and Devon were the site of a Jacobite rebellion in 1715 led by James Paynter of St. Columb. This coincided with the larger and better-known "Fifteen Rebellion" which took place in Scotland and the north of England. However, the Cornish uprising was quickly quashed by the authorities. James Paynter was tried for High Treason but claiming his right as a Cornish tinner was tried in front of a jury of other Cornish tinners and was cleared.

Industrialised communities have long appeared to weaken the pre-eminence of the Church of England, and as the Cornish people were readily involved in mining, a rift developed between the Cornish people and their Anglican clergy in the early 18th century.[63] Resisting the established church, many ordinary Cornish people were Roman Catholic or non-religious until the late 18th century, when Methodism was introduced to Cornwall during a series of visits by John and Charles Wesley. Methodist separation from the Church of England was made formal in 1795.

In 1841 there were ten hundreds of Cornwall: Stratton, Lesnewth and Trigg; East and West Wivelshire; Powder; Pydar; Kerrier; Penwith; and Scilly. The shire suffix has been attached to several of these, notably: the first three formed Triggshire; East and West appear to be divisions of Wivelshire; Powdershire and Pydarshire. The old names of Kerrier and Penwith have been re-used for modern local government districts. The ecclesiastical division within Cornwall into rural deaneries used versions of the same names though the areas did not correspond exactly: Trigg Major, Trigg Minor, East Wivelshire, West Wivelshire, Powder, Pydar, Kerrier and Penwith were all deaneries of the Diocese of Exeter but boundaries were altered in 1875 when five more deaneries were created (from December 1876 all in the Diocese of Truro).[64]

The peak of smuggling in Cornwall was evident in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Import taxes and other duties on goods led to a number of traders and consumers evading the extra price burden by using the county's ragged coastline as a landing point for dutiable goods. The most trafficked items were brandy, lace and tobacco, imported from Continental Europe. The Jamaica Inn pub on Bodmin Moor has been noted for its early association with smuggling. By the 19th century, a large proportion of the population of Cornwall – an estimated 10,000 people, including women and children – were thought to take part in the smuggling business. The rate of smuggling subsided in the coming century, and by the 1830s, two factors were established to have combined to make smuggling less worthwhile – improvements in coastguard services which lead to capture, and the reduction of excise duties on imported goods.[65]

A revival of interest in Cornish studies began in the early 20th century with the work of Henry Jenner and the building of links with the other five Celtic nations.

A political party, Mebyon Kernow, was formed in 1951 to attempt to serve the interests of Cornwall and to support greater self-government for the county. The party has had elected a number of members to county, district, town and parish councils but has had no national success, although the more widespread use of the Flag of St Piran has been accredited to this party.[citation needed]

There have been some developments in the recognition of Cornish identity or ethnicity. In 2001 for the first time in the UK the inhabitants of Cornwall could record their ethnicity as Cornish on the national census, and in 2004 the schools census in Cornwall carried a Cornish option as a subdivision of white British. On 24 April 2014 it was announced that Cornish people will be granted minority status under the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[66]

General: