Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Humidity and hygrometry |

|---|

|

| Specific concepts |

| General concepts |

| Measures and instruments |

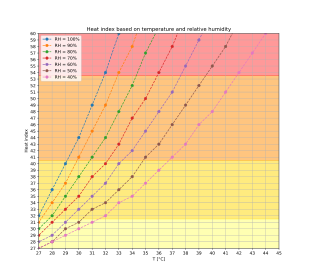

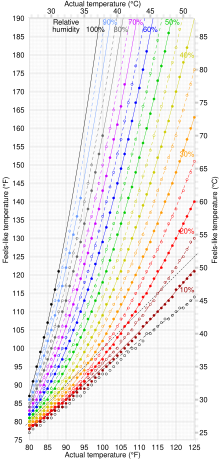

The heat index (HI) is an index that combines air temperature and relative humidity, in shaded areas, to posit a human-perceived equivalent temperature, as how hot it would feel if the humidity were some other value in the shade. For example, when the temperature is 32 °C (90 °F) with 70% relative humidity, the heat index is 41 °C (106 °F) (see table below). The heat index is meant to describe experienced temperatures in the shade, but it does not take into account heating from direct sunlight, physical activity or cooling from wind.

The human body normally cools itself by evaporation of sweat. High relative humidity reduces evaporation and cooling, increasing discomfort and potential heat stress. Different individuals perceive heat differently due to body shape, metabolism, level of hydration, pregnancy, or other physical conditions. Measurement of perceived temperature has been based on reports of how hot subjects feel under controlled conditions of temperature and humidity. Besides the heat index, other measures of apparent temperature include the Canadian humidex, the wet-bulb globe temperature, "relative outdoor temperature", and the proprietary "RealFeel".

The heat index was developed in 1979 by Robert G. Steadman.[1][2] Like the wind chill index, the heat index contains assumptions about the human body mass and height, clothing, amount of physical activity, individual heat tolerance, sunlight and ultraviolet radiation exposure, and the wind speed. Significant deviations from these will result in heat index values which do not accurately reflect the perceived temperature.[3]

In Canada, the similar humidex (a Canadian innovation introduced in 1965)[4] is used in place of the heat index. While both the humidex and the heat index are calculated using dew point, the humidex uses a dew point of 7 °C (45 °F) as a base, whereas the heat index uses a dew point base of 14 °C (57 °F).[further explanation needed] Further, the heat index uses heat balance equations which account for many variables other than vapor pressure, which is used exclusively in the humidex calculation. A joint committee[who?] formed by the United States and Canada to resolve differences has since been disbanded.[citation needed]

The heat index of a given combination of (dry-bulb) temperature and humidity is defined as the dry-bulb temperature which would feel the same if the water vapor pressure were 1.6 kPa. Quoting Steadman, "Thus, for instance, an apparent temperature of 24 °C (75 °F) refers to the same level of sultriness, and the same clothing requirements, as a dry-bulb temperature of 24 °C (75 °F) with a vapor pressure of 1.6 kPa."[1]

This vapor pressure corresponds for example to an air temperature of 29 °C (84 °F) and relative humidity of 40% in the sea-level psychrometric chart, and in Steadman's table at 40% RH the apparent temperature is equal to the true temperature between 26–31 °C (79–88 °F). At standard atmospheric pressure (101.325 kPa), this baseline also corresponds to a dew point of 14 °C (57 °F) and a mixing ratio of 0.01 (10 g of water vapor per kilogram of dry air).[1]

A given value of relative humidity causes larger increases in the heat index at higher temperatures. For example, at approximately 27 °C (81 °F), the heat index will agree with the actual temperature if the relative humidity is 45%, but at 43 °C (109 °F), any relative-humidity reading above 18% will make the heat index higher than 43 °C.[5]

It has been suggested that the equation described is valid only if the temperature is 27 °C (81 °F) or more.[6] The relative humidity threshold, below which a heat index calculation will return a number equal to or lower than the air temperature (a lower heat index is generally considered invalid), varies with temperature and is not linear. The threshold is commonly set at an arbitrary 40%.[5]

The heat index and its counterpart the humidex both take into account only two variables, shade temperature and atmospheric moisture (humidity), thus providing only a limited estimate of thermal comfort. Additional factors such as wind, sunshine and individual clothing choices also affect perceived temperature; these factors are parameterized as constants in the heat index formula. Wind, for example, is assumed to be 5 knots (9.3 km/h).[5] Wind passing over wet or sweaty skin causes evaporation and a wind chill effect that the heat index does not measure. The other major factor is sunshine; standing in direct sunlight can add up to 15 °F (8.3 °C) to the apparent heat compared to shade.[7] There have been attempts to create a universal apparent temperature, such as the wet-bulb globe temperature, "relative outdoor temperature", "feels like", or the proprietary "RealFeel".

Outdoors in open conditions, as the relative humidity increases, first haze and ultimately a thicker cloud cover develops, reducing the amount of direct sunlight reaching the surface. Thus, there is an inverse relationship between maximum potential temperature and maximum potential relative humidity. Because of this factor, it was once believed that the highest heat index reading actually attainable anywhere on Earth was approximately 71 °C (160 °F). However, in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia on July 8, 2003, the dew point was 35 °C (95 °F) while the temperature was 42 °C (108 °F), resulting in a heat index of 81 °C (178 °F).[8] On August 28, 2024, a weather station in southern Iran recorded a heat index of 82.2 °C (180.0 °F), which will be a new record if confirmed.[9]

The human body requires evaporative cooling to prevent overheating. Wet-bulb temperature and Wet Bulb Globe Temperature are used to determine the ability of a body to eliminate excess heat. A sustained wet-bulb temperature of about 35 °C (95 °F) can be fatal to healthy people; at this temperature our bodies switch from shedding heat to the environment, to gaining heat from it.[10] Thus a wet bulb temperature of 35 °C (95 °F) is the threshold beyond which the body is no longer able to adequately cool itself.[11]

The table below is from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The columns begin at 80 °F (27 °C), but there is also a heat index effect at 79 °F (26 °C) and similar temperatures when there is high humidity.

Temperature Relative humidity

|

80 °F (27 °C) | 82 °F (28 °C) | 84 °F (29 °C) | 86 °F (30 °C) | 88 °F (31 °C) | 90 °F (32 °C) | 92 °F (33 °C) | 94 °F (34 °C) | 96 °F (36 °C) | 98 °F (37 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 102 °F (39 °C) | 104 °F (40 °C) | 106 °F (41 °C) | 108 °F (42 °C) | 110 °F (43 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40% | 80 °F (27 °C) | 81 °F (27 °C) | 83 °F (28 °C) | 85 °F (29 °C) | 88 °F (31 °C) | 91 °F (33 °C) | 94 °F (34 °C) | 97 °F (36 °C) | 101 °F (38 °C) | 105 °F (41 °C) | 109 °F (43 °C) | 114 °F (46 °C) | 119 °F (48 °C) | 124 °F (51 °C) | 130 °F (54 °C) | 136 °F (58 °C) |

| 45% | 80 °F (27 °C) | 82 °F (28 °C) | 84 °F (29 °C) | 87 °F (31 °C) | 89 °F (32 °C) | 93 °F (34 °C) | 96 °F (36 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 104 °F (40 °C) | 109 °F (43 °C) | 114 °F (46 °C) | 119 °F (48 °C) | 124 °F (51 °C) | 130 °F (54 °C) | 137 °F (58 °C) | |

| 50% | 81 °F (27 °C) | 83 °F (28 °C) | 85 °F (29 °C) | 88 °F (31 °C) | 91 °F (33 °C) | 95 °F (35 °C) | 99 °F (37 °C) | 103 °F (39 °C) | 108 °F (42 °C) | 113 °F (45 °C) | 118 °F (48 °C) | 124 °F (51 °C) | 131 °F (55 °C) | 137 °F (58 °C) | ||

| 55% | 81 °F (27 °C) | 84 °F (29 °C) | 86 °F (30 °C) | 89 °F (32 °C) | 93 °F (34 °C) | 97 °F (36 °C) | 101 °F (38 °C) | 106 °F (41 °C) | 112 °F (44 °C) | 117 °F (47 °C) | 124 °F (51 °C) | 130 °F (54 °C) | 137 °F (58 °C) | |||

| 60% | 82 °F (28 °C) | 84 °F (29 °C) | 88 °F (31 °C) | 91 °F (33 °C) | 95 °F (35 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 105 °F (41 °C) | 110 °F (43 °C) | 116 °F (47 °C) | 123 °F (51 °C) | 129 °F (54 °C) | 137 °F (58 °C) | ||||

| 65% | 82 °F (28 °C) | 85 °F (29 °C) | 89 °F (32 °C) | 93 °F (34 °C) | 98 °F (37 °C) | 103 °F (39 °C) | 108 °F (42 °C) | 114 °F (46 °C) | 121 °F (49 °C) | 128 °F (53 °C) | 136 °F (58 °C) | |||||

| 70% | 83 °F (28 °C) | 86 °F (30 °C) | 90 °F (32 °C) | 95 °F (35 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 105 °F (41 °C) | 112 °F (44 °C) | 119 °F (48 °C) | 126 °F (52 °C) | 134 °F (57 °C) | ||||||

| 75% | 84 °F (29 °C) | 88 °F (31 °C) | 92 °F (33 °C) | 97 °F (36 °C) | 103 °F (39 °C) | 109 °F (43 °C) | 116 °F (47 °C) | 124 °F (51 °C) | 132 °F (56 °C) | |||||||

| 80% | 84 °F (29 °C) | 89 °F (32 °C) | 94 °F (34 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 106 °F (41 °C) | 113 °F (45 °C) | 121 °F (49 °C) | 129 °F (54 °C) | ||||||||

| 85% | 85 °F (29 °C) | 90 °F (32 °C) | 96 °F (36 °C) | 102 °F (39 °C) | 110 °F (43 °C) | 117 °F (47 °C) | 126 °F (52 °C) | 135 °F (57 °C) | ||||||||

| 90% | 86 °F (30 °C) | 91 °F (33 °C) | 98 °F (37 °C) | 105 °F (41 °C) | 113 °F (45 °C) | 122 °F (50 °C) | 131 °F (55 °C) | |||||||||

| 95% | 86 °F (30 °C) | 93 °F (34 °C) | 100 °F (38 °C) | 108 °F (42 °C) | 117 °F (47 °C) | 127 °F (53 °C) | ||||||||||

| 100% | 87 °F (31 °C) | 95 °F (35 °C) | 103 °F (39 °C) | 112 °F (44 °C) | 121 °F (49 °C) | 132 °F (56 °C) |

For example, if the air temperature is 96 °F (36 °C) and the relative humidity is 65%, the heat index is 121 °F (49 °C)

| Temperature | Notes |

|---|---|

| 27–32 °C (81–90 °F) |

Caution: fatigue is possible with prolonged exposure and activity. Continuing activity could result in heat cramps. |

| 32–41 °C (90–106 °F) |

Extreme caution: heat cramps and heat exhaustion are possible. Continuing activity could result in heat stroke. |

| 41–54 °C (106–129 °F) |

Danger: heat cramps and heat exhaustion are likely; heat stroke is probable with continued activity. |

| over 54 °C (129 °F) |

Extreme danger: heat stroke is imminent. |

Exposure to full sunshine can increase heat index values by up to 8 °C (14 °F).[12]

There are many formulas devised to approximate the original tables by Steadman. Anderson et al. (2013),[13] NWS (2011), Jonson and Long (2004), and Schoen (2005) have lesser residuals in this order. The former two are a set of polynomials, but the third one is by a single formula with exponential functions.

The formula below approximates the heat index in degrees Fahrenheit, to within ±1.3 °F (0.7 °C). It is the result of a multivariate fit (temperature equal to or greater than 80 °F (27 °C) and relative humidity equal to or greater than 40%) to a model of the human body.[1][14] This equation reproduces the above NOAA National Weather Service table (except the values at 90 °F (32 °C) & 45%/70% relative humidity vary unrounded by less than ±1, respectively).

where

The following coefficients can be used to determine the heat index when the temperature is given in degrees Celsius, where

An alternative set of constants for this equation that is within ±3 °F (1.7 °C) of the NWS master table for all humidities from 0 to 80% and all temperatures between 70 and 115 °F (21–46 °C) and all heat indices below 150 °F (66 °C) is:

A further alternate is this:[15]

where

For example, using this last formula, with temperature 90 °F (32 °C) and relative humidity (RH) of 85%, the result would be: 114.9 °F (46.1 °C).

The heat index does not work well with extreme conditions, like supersaturation of air, when the air is more than 100% saturated with water. David Romps, a physicist and climate scientist at the University of California, Berkeley and his graduate student Yi-Chuan Lu, found that the heat index was underestimating the severity of intense heat waves, such as the 1995 Chicago heat wave.[16]

Other issues with the heat index include the unavailability of precise humidity data in many geographical regions, the assumption that the person is healthy, and the assumption that the person has easy access to water and shade.[17]