Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

"Edda" (/ˈɛdə/; Old Norse Edda, plural Eddur) is an Old Norse term that has been applied by modern scholars to the collective of two Medieval Icelandic literary works: what is now known as the Prose Edda and an older collection of poems (without an original title) now known as the Poetic Edda. The term historically referred only to the Prose Edda, but this usage has fallen out of favour because of confusion with the other work. Both works were recorded in Iceland during the 13th century in Icelandic, although they contain material from earlier traditional sources, reaching back into the Viking Age. The books provide the main sources for medieval skaldic tradition in Iceland and for Norse mythology.

The Edda has been criticized for imposing Snorri Sturluson's own Christian views on Norse mythology. In particular the clean-cut explanation of what happens to a soul after death as understood in the Edda contradicts other sources on death in Norse mythology.[1]

At least five hypotheses have been suggested for the origins of the word edda:

The Poetic Edda, also known as Sæmundar Edda or the Elder Edda, is a collection of Old Norse poems from the Icelandic medieval manuscript Codex Regius ("Royal Book"). Along with the Prose Edda, the Poetic Edda is the most expansive source on Norse mythology. The first part of the Codex Regius preserves poems that narrate the creation and foretold destruction and rebirth of the Old Norse mythological world as well as individual myths about gods concerning Norse deities. The poems in the second part narrate legends about Norse heroes and heroines, such as Sigurd, Brynhildr and Gunnar.

It consists of two parts. The first part has 10 songs about gods, and the second one has 19 songs about heroes.

The Codex Regius was written in the 13th century, but nothing is known of its whereabouts until 1643, when it came into the possession of Brynjólfur Sveinsson, then the Church of Iceland's Bishop of Skálholt. At that time, versions of the Prose Edda were well known in Iceland, but scholars speculated that there once was another Edda—an Elder Edda—which contained the pagan poems Snorri quotes in his book. When the Codex Regius was discovered, it seemed that this speculation had proven correct. Brynjólfur attributed the manuscript to Sæmundr the Learned, a larger-than-life 12th century Icelandic priest. While this attribution is rejected by modern scholars, the name Sæmundar Edda is still sometimes encountered.

Bishop Brynjólfur sent the Codex Regius as a present to King Christian IV of Denmark, hence the name Codex Regius. For centuries it was stored in the Royal Library in Copenhagen but in 1971 it was returned to Iceland.

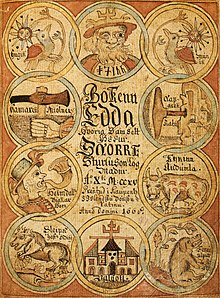

The Prose Edda, sometimes referred to as the Younger Edda or Snorri's Edda, is an Icelandic manual of poetics which also contains many mythological stories. Its purpose was to enable Icelandic poets and readers to understand the subtleties of alliterative verse, and to grasp the mythological allusions behind the many kennings that were used in skaldic poetry.

It was written by the Icelandic scholar and historian Snorri Sturluson around 1220. It survives in four known manuscripts and three fragments, written down from about 1300 to about 1600.[6]

The Prose Edda consists of a Prologue and three separate books: Gylfaginning, concerning the creation and foretold destruction and rebirth of the Norse mythical world; Skáldskaparmál, a dialogue between Ægir, a Norse god connected with the sea, and Bragi, the skaldic god of poetry; and Háttatal, a demonstration of verse forms used in Norse mythology.